32°46′11″N 79°55′49″W / 32.7698°N 79.9304°W

| White Point Garden | |

|---|---|

| Location | 2 Murray Blvd. |

| Area | 5.7 acres (2.3 ha) |

| Created | 1800s |

| Operated by | City of Charleston |

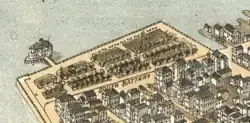

White Point Garden is a 5.7 acre public park located in peninsular Charleston, South Carolina, at the tip of the peninsula. It is the southern terminus for the Battery, a defensive seawall and promenade. It is bounded by East Battery (to the east), Murray Blvd. (to the south), King St. (to the west), and South Battery (to the north).

History

The southern tip of Charleston's peninsula was originally known as the South Bay[1] and later Oyster Point. In the early 19th century it was renamed White Point. Later, landfill projects resulted in the sharp-edged terminus of the peninsula.[2]

From about 1840 to 1881, a public bathing house stood at the end of King Street.[3] The building was constructed by James English, William Patton, and Henry L. Pinckney at a cost of about $25,000. A cake and ice cream parlor was operated on the top floor of the bathing house. The bathing house suffered several injuries by storms but was rebuilt each time. It was removed in 1881 as White Point Garden and the waterfront were filled in.[4]

Throughout the 19th and early 20th century, from the Reconstruction era to the emergence of Jim Crow laws, Black Charlestonians occupied public spaces like White Point Garden on Independence Day to celebrate freedom from slavery. On any other day it was not permitted for blacks to enter the public park, and they were not allowed to sit on public benches.[5]

White Point Gardens was commonly known as a gay cruising spot by Charlestonians well into the 20th century. Because of the prominence of gay cruising in the public park, efforts were made to close down the public restrooms.[6]

Features

For more than a century, White Point Garden has been a repository of relics and memorials, with a largely military theme.[7]

In July 1897, two 10-inch columbiads that had been stored at Fort Sumter after the American Civil War, were given by the federal government to a park in Kokomo, Indiana, for use as ornamentation.[8] It was unknown whether the particular guns had actually been in service during the Civil War.[9] On July 30, 1897, an opinion piece appeared in the Charleston Evening Post in response to the news of the giveaway to Kokomo that suggested that the remaining guns at Fort Sumter (perhaps twenty) be secured for use in Charleston's own parks.[10] Later that year, Charleston's City Council voted in favor (with one vote in opposition) to request the balance of the guns from the United States War Department.[11] The War Department eventually loaned ten guns to Charleston. Some were put on display at the then-Thomson Auditorium temporarily, while two of the guns from USS Keokuk were installed at White Point Garden in 1900. Keokuk was sunk by Charleston's forts in April 1863; the Confederates later salvaged and used these guns.[12]

Placed at irregular intervals around three sides of the perimeter of White Point Garden are several military relics. Along East Battery are the 11-inch Dahlgren gun from the USS Keokuk that fired shells at Fort Sumter in 1863 and two Confederate columbiads (large cannons) that were used in the defense of Fort Sumter. On Murray Blvd. there are several more artillery pieces: a rare 7-inch Brooke rifle (a large cannon) that was found at Fort Johnson and four 13-inch Union mortars (weighing 17,000 pounds each). On the King St. side are a 1918 World War I howitzer; a French cannon of Revolutionary War vintage that was found in Camden, South Carolina; and a rapid-fire gun from a Spanish ship captured during the Spanish–American War.[7]

Among the many cannon on display is one fake. In the early 1900s, a 4-pound British cannon thought to be of the colonial era was lodged halfway into the middle of Longitude Alley, supposedly to prevent dray carriages from using the narrow passage. In 1933, the City decided to unearth the cannon and relocate it in White Point Garden at the intersection of a projected Church Street extension and Murray Blvd. The residents of Longitude Lane were unhappy at the loss of their relic, and demanded its return, but the City was not moved.[13] Meanwhile, a prankster hired a foundry to create a fake cannon of the same era. He aged the cannon by submerging it in water for six months at his dock and then sold it to an antique store in Beaufort, South Carolina. When it was "discovered" there, it was bought by a visitor from the North and brought to Charleston. The buyer offered it to the residents of Longitude Lane to replace their cannon, but they rejected the offer, instead demanding the original cannon. The City, however, believed the cannon to be genuine and acquired it for display too. The cannon fooled many people, but it suffered a telltale anachronism: because the foundry did not have the tools to fabricate an actual cannon, the foundry instead poured molten metal around a section of cast iron pipe even though cast iron pipe was not used even in large cities until the 19th century.[14] The Longitude Alley cannon stood across the park at the intersection of Church St. and South Battery; it was removed by the City following vandalism (possibly an attempted theft) and then either lost or stolen. It has not been seen since.[15]

Along the center walkway in line with Church St. is The Defenders of Fort Moultrie, honoring South Carolinian soldiers during the Battle of Sullivan's Island. It is often called the Jasper Monument since it shows a statue of Sergeant William Jasper, a hero of the Revolutionary War battle won by the colonists at Fort Moultrie on Sullivan's Island on June 28, 1776. The memorial was added in 1877.[7]

At the northeast corner is a marker, erected in 1943, to the Gentleman Pirate Stede Bonnet. The monument commemorates the hanging near that site of pirate captain Stede Bonnet and his crew in 1718, as well as the 1719 hanging of Richard Worley's pirates. The monument states that 29 of Bonnet's crew were executed close by. Although 29 of Bonnet's crew were sentenced to death, the evidence suggests that only 22 were actually hanged.[7][16]

Located across from Meeting Street in the center of the park, a bandstand, begun in 1906 and completed in 1907, is a memorial to Mrs. George W. Williams by her daughter, Mrs. Martha W. Carrington. The bandstand, designed by William Martin Aiken and built by Robert McArtney,[17] cost more than $5,000 when it was built and hosted regular concerts. The new bandstand replaced a dilapidated wood structure.[18] The inaugural concert for the new bandstand was held on June 28, 1907 to celebrate Carolina Day with music by Metz's Military Band.[19]

In 1978, in response to neighbors about noise and commercial activity, concerts were outlawed at the bandstand. In 1985, the bandstand received a $30,000 restoration (including $8,000 in private funds), and a request was made to resume musical performances. The request was rejected, and although the bandstand is used for weddings and limited special events, concerts are not allowed.[20] In 1934, the pavilion was raised three feet and restrooms were installed under the structure.[18] Because of law enforcement issues, the bathrooms were locked at some point. In 2008, the City announced a plan to restore the bandstand and lower it to its original height of three instead of six feet.[21] The restoration was completed in April, 2010.

In 1962, Charleston sculptor Willard Hirsch was commissioned by Miss Sally Carrington to create a bronze statue of a dancing girl. The statue was a gift to the City and was installed as a water fountain in White Point Garden on an especially low granite base so that children could make easy use of it.[22]

Among the military relics on display was once the capstan of the USS Maine. The capstan was salvaged from the Maine when it was raised from the bottom of Havana Harbor, and its parts were meted out to communities all over the country. The capstan was donated to Charleston by Sen. Ben Tillman but sat in the basement of City Hall for several years before being installed in Hampton Park. Later, the capstan was relocated to the U.S. Navy Base and then later to White Point Garden. It was displayed atop a concrete base on the eastern edge of the park.[23] In 2007, the capstan was removed, and a statue of William Moultrie was installed in the same location. The 8-foot statue, atop a 7-foot pedestal, depicts a uniformed Moultrie, sword in sheath, holding his hat at his side as he appears to survey Charleston Harbor. It was sculpted by John Ney Michel.[24]

At the southeastern corner of White Point Garden is a large allegorical statue installed in 1932 by the United Daughters of the Confederacy. The monument titled, Confederate Defenders of Charleston, commemorates the soldiers who fought for their city and the southern States during the Civil War. The bronze statue is 12 feet tall and rests on a granite base 13 feet tall. The sculptor was Hermon Atkins MacNeil.[7]

Near the southwest corner of the park is a memorial to the crew of the USS Amberjack, a submarine that was sunk during World War II, and 51 other American subs lost during the conflict.[7]

Also located near the southwest corner of the park is the 20-foot tall, granite Hobson Monument. On April 26, 1952, the U.S. destroyer Hobson was cut in half and sunk after being in a collision with the American aircraft carrier Wasp. The stones used in the platform come from the 38 home states of the 176 sailors who died. The Hobson was built at the Charleston Navy Yard.[25]

At the meeting of Meeting St. and South Battery is a memorial to the crew of the H.L. Hunley. Added in 1899, the granite monument recognizes the first successful submarine, the Hunley, which eventually sank in Charleston Harbor following a successful attack on the USS Housatonic.[7]

Along the center walkway in the park, halfway between Church and Meeting, is a bronze bust, atop a granite column, of William Gilmore Simms (1806-1870), a poet, novelist, and historian, whose history of South Carolina served as the definitive textbook on state history for much of the 20th century. Sculpted by John Quincy Adams Ward, the monument was added in 1879.[7][26] The base for the bust was designed by Edward Brickell White.[27]

Notes

- ↑ John Marshall. "David Rumsey Map Collection=1807" (Map). Old Maps Online. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- ↑ Jack Leland (April 11, 1984). "Battery Afternoon Tour on Tap Today". Charleston News & Courier. p. 9B. Retrieved November 15, 2012.

- ↑ "The Bathing House". News and Courier. December 8, 1881. p. 4.

- ↑ "The Bathing-House". Charleston News & Courier. December 8, 1881. p. 4. Retrieved December 3, 2012.

- ↑ Roberts, Blain; Kytle, Ethan J. (2012). "Looking the Thing in the Face: Slavery, Race, and the Commemorative Landscape in Charleston, South Carolina, 1865–2010". The Journal of Southern History. 78 (3): 639–684. ISSN 0022-4642. JSTOR 23247373.

- ↑ Manno, Adam (July 25, 2018). "Charleston's public gay spaces have slowly disappeared. Do we need them back?". Charleston City Paper. Retrieved December 27, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Jason Hardin (September 2, 2001). "A Guide to the Monuments and History of White Point". Charleston Post & Courier. p. 10A. Retrieved November 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Sumter's Guns". Evening Post. July 29, 1897. p. 5. Retrieved July 3, 2015.

- ↑ "Guns From Fort Sumter". News & Courier. Charleston, South Carolina. July 30, 1897. p. 8. Retrieved July 3, 2015.

- ↑ "Sumter's Guns". Evening Post. Charleston, South Carolina. July 30, 1897. p. 5. Retrieved July 3, 2015.

- ↑ "Sumter's Guns". Evening Post. Charleston, South Carolina. November 6, 1897. p. 5. Retrieved July 3, 2015.

- ↑ "Mounting An Old War Gun". Evening Post. Charleston, South Carolina. November 23, 1900. p. 5. Retrieved July 3, 2015.

- ↑ "Rusty Old Cannon Is Prize in War of Longitude Lane". Charleston News & Courier. March 5, 1933. p. A1. Retrieved November 15, 2012.

- ↑ Skip Johnson (July 16, 1984). "Fake Revolutionary War Cannon Continues to Fool Experts". Charleston News & Courier. p. 5A.

- ↑ Jason Hardin (October 7, 2001). "Mystery of Lost Cannon Endures". Charleston Post & Courier. p. B1. Retrieved November 15, 2012.

- ↑ Thomas Bayley Howell & William Cobbett, A Complete Collection of State Trials and Proceedings for High Treason and Other Crimes and Misdemanors, Vol. XV, London, 1816, p. 1290.

- ↑ Robert P. Stockton (July 20, 1981). "Music Pavilion Designed by Aiken". Charleston News & Courier. p. B1. Retrieved November 15, 2012.

- 1 2 "Do You Know Your Charleston?". Charleston News & Courier. October 29, 1934. p. 10. Retrieved November 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Memorial Band Stand on White Point Gardens". Charleston News & Courier. June 28, 1907. p. 12. Retrieved November 15, 2012.

- ↑ Charles Rowe (July 2, 1985). "Mayor Riley See Little Likelihood White Point Concerts Will Resume". Charleston News & Courier. p. 2B. Retrieved November 15, 2012.

- ↑ David Slade (September 23, 2008). "Face-Lift for a Landmark". Charleston Post & Courier. p. 3B. Retrieved November 15, 2012.

- ↑ "White Point Gardens to Get New Fountain". Charleston News & Courier. May 3, 1962. p. 5A. Retrieved November 15, 2012.

- ↑ Jack Leland (June 2, 1986). "Capstan of the Maine a Memento of a Key U.S. Conflict". Charleston News & Courier. p. 2B. Retrieved November 15, 2012.

- ↑ David Slade (June 29, 2007). "Moultrie's Statue Unveiled amid Pageantry, Pomp". Charleston Post & Courier. Retrieved November 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Battery Monument Records Tragedy". Charleston News & Courier. August 27, 1962. p. 11A. Retrieved November 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Odds and Ends". News and Courier. Charleston, South Carolina. February 28, 1879. p. 4.

- ↑ "The Simms Memorial". News and Courier. June 6, 1879. p. 4.