| Wide Boy | |

|---|---|

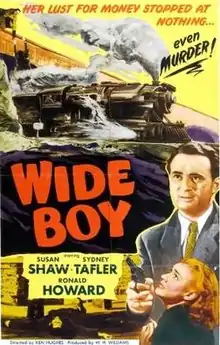

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Ken Hughes |

| Written by | William Fairchild (uncredited) |

| Based on | an original story by Rex Rienits |

| Produced by | William H. Williams executive Nat Cohen Stuart Levy |

| Starring | Susan Shaw Sydney Tafler Ronald Howard |

| Cinematography | Josef Ambor |

| Edited by | Geoffrey Muller |

| Music by | Eric Spear |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Anglo-Amalgamated (UK) |

Release date | April 1952 |

Running time | 67 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | £7,000[1] |

Wide Boy is a 1952 British crime film directed by Ken Hughes and starring Susan Shaw, Sydney Tafler and Ronald Howard.[2]

It was Hughes' feature directorial debut.[3][4] He later called it "pretty terrible".[1]

Plot

Benny is a black marketeer, dealing in stolen goods; after yet another arrest Benny meets up with his girlfriend Molly, a hairdresser, and they go somewhere different for them, a bar called The Flamingo.

There are only two other customers there at the bar, Robert Mannering and his mistress Caroline Blaine, and it is clear from their conversation that he is a famous surgeon whose wife is dying. Benny notices Caroline's smart handbag, and manages to steal Caroline's wallet. Benny then realises that he recognises Mannering as a famous surgeon. Mannering and Caroline leave shortly afterwards, followed by Benny and Molly, who is unaware of Benny's theft, but Mannering and Caroline return to the bar as they realise that the wallet was stolen by Benny, although the barman George says he did not know Benny as he had never been to the bar before.

Back in his room Benny finds £32 in the wallet, but also a letter from Mannering to Caroline, which makes it clear that he is having an affair with her and that his wife must not find out. He decides to blackmail the couple, and Mannering agrees to pay him as he does not want any scandal as he is trying to get voted onto the Council of the Royal College of Surgeons.

Mannering agrees to meet Benny and pay £200 for the letter, but finds that he has been cheated and does not get the letter back. Benny spends some of the money on a watch for Molly, which he says cost him £60. He then rings up Mannering again, this time asking for £300, but as he goes to the meeting he buys a gun. When he meets Mannering they swap the money and the letter, but Benny tells Mannering, falsely, that he took a photo of the letter and has the negative, suggesting that he intends to continue blackmailing Mannering. The latter grabs hold of Benny, but in the ensuing struggle Benny shoots Mannering dead.

The police investigation soon leads them first to Caroline, and then George, the barman at the Flamingo, who identifies Benny from police files. They go to Benny's address but he manages to escape and goes to a crook, Rocco, to try and get out of the country. Rocco however wants £400, so Benny decides to ask Molly to give him back the watch so that he can raise the money. By chance however Caroline makes an appointment at the hairdressers where Molly works, and inadvertently Molly makes Caroline realise that it was her with Benny in the Flamingo that evening; she then hears a conversation between Molly and Benny on the phone, arranging a meeting at a railway bridge that evening. She tells the police, who are waiting for Benny when he turns up; he tries to escape by scrambling over the bridge but falls to his death on the tracks below.

Cast

- Sydney Tafler as Benny

- Susan Shaw as Molly

- Ronald Howard as Chief Inspector Carson

- Melissa Stribling as Caroline Blaine

- Colin Tapley as Robert Mannering

- Laidman Browne as Pop

- Gerald Case as Detective Sgt Stott

- Glyn Houston as George

- Ian Wallace as Mario

- Dorothy Bramhall as Felicity

- Martin Benson as Rocco

- Helen Christie as Sally

- Peggy Banks as receptionist

Production

The story was by Rex Rienits who used it for a radio play and a novel. Rienits wrote the story for star Sydney Tafler, who had been in Assassin for Hire written by Rienits.[5]

Film rights were bought by Anglo Amalgamated.[6] Filming started in Pinewood at the end of January 1952.[7]

Reception

The Monthly Film Bulletin said the story "has action and movement but is not, as a whole, particularly competent."[2]

BFI Screenoline said Hughes "displays a keen awareness of class differences and, although opportunities for character development are strictly limited by the film's brief running time, he manages to avoid caricature and sketches a series of contrasting milieus with the authenticity brought by the careful observation of detail. Hughes also takes the trouble to make sure that, while conventional morality is upheld, we retain some shred of sympathy for his wide boy.:[8]

The Independent wrote that the film "rarely features on the official list of 'great British films of 1952' but it does boast a winning performance from Sidney [sic] Tafler in the title role amid a bomb-ravaged London of quite amazing shoddiness."[9]

Sight and Sound wrote "Ken Hughes' direction captures an existence of cheap dreams, 20-shillings-per-week lodging houses and harshly neon-lit streets; Tafler's "glycerine mouthed" spiv is far more charismatic than Ronald Howard's police inspector."[10]

Filmink called it "stripped back, atmospheric entertainment, without an ounce of fat on it."[11]

Radio

The radio play was meant to be broadcast on the BBC in early 1952 but this was delayed due to concerns by the BBC about its subject matter.[12][13]

It was adapted for Australian radio in 1953.[14] The cast included Ray Barrett.[15] There were later productions in 1956.

Short Story

Rienits adapted the story as a short story. It was published in his novel Assassin for Hire.[16]

Remake

The story was adapted for Australian TV in the TV play Bodgie (1959), where it was relocated to an Australian setting.[17]

References

- 1 2 16 July 1970, Cromwell knocked about a bit. The Guardian. p. 8.

- 1 2 Wide Boy Monthly Film Bulletin; London Vol. 19, Iss. 216, (1 Jan 1952): 82.

- ↑ "Ken Hughes". Variety. 1 May 2001.

- ↑ "Ken Hughes Obituary". The Daily Telegraph. 1 May 2001. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- ↑ "Australian Writer Succeeds in London". The Age. No. 30, 161. Victoria, Australia. 29 December 1951. p. 4 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Overseas movie gossip". The Australian Women's Weekly. Vol. 19, no. 28. Australia. 12 December 1951. p. 34 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Hat-Trick By Film Script Man". The Newcastle Sun. New South Wales, Australia. 20 December 1951. p. 7 – via Trove.

- ↑ Wide Boy at BFI Screenonline.

- ↑ FILM: Attack of the B-movie ; Cheap, low-quality, second features were a cinema staple until TV killed them. ANDREW ROBERTS salutes a neglected genre: [First Edition] Roberts, Andrew. The Independent; 6 Jan 2006: 13.

- ↑ Roberts, Andrew. Playing to the stalls. Sight & Sound; London Vol. 20, Iss. 1, (Jan 2010): 10-11,2.

- ↑ Vagg, Stephen (14 November 2020). "Ken Hughes Forgotten Auteur". Filmink.

- ↑ "Broadcast of Play Cancelled". The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 - 1954). Perth, WA: National Library of Australia. 7 February 1952. p. 9.

- ↑ "BBC Rejects New Play". Variety. 27 February 1952. p. 11.

- ↑ "Saturday Night Drama: "Wide Boy"". South Coast Times and Wollongong Argus. Vol. LIII, no. 3. New South Wales, Australia. 12 January 1953. p. 2 (South Coast Times AND Wollongong Argus Feature Section) – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Plays and Players". The Sun. No. 13, 397. New South Wales, Australia. 16 January 1953. p. 10 (Late Final Extra) – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Crime Shelf". The Mail (Adelaide). Vol. 42, no. 2, 109. South Australia. 8 November 1952. p. 2 (Sunday Magazine) – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Bodgies in Drama", Sydney Morning Herald, 10 August 1959 p 13