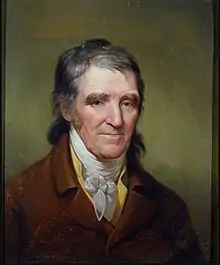

William Findley | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Pennsylvania | |

| In office March 4, 1803 – March 3, 1817 | |

| Preceded by | John Stewart |

| Succeeded by | David Marchand |

| Constituency | 8th district (1803–1813) 11th district (1813–1817) |

| In office March 4, 1791 – March 3, 1799 | |

| Preceded by | district established |

| Succeeded by | John Smilie |

| Constituency | 8th district (1791–1793) at-large district (seat H) (1793–1795) 11th district (1795–1799) |

| Member of the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania from Westmoreland County | |

| In office November 25, 1789 – December 20, 1790 | |

| Preceded by | John Proctor |

| Succeeded by | Position dissolved |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1741 Ireland |

| Died | April 4, 1821 (aged 80) Greensburg, Pennsylvania |

| Political party | Anti-Administration Republican |

| Profession | Politician, farmer |

William Findley (c. 1741 – April 4, 1821) was an Irish-born farmer and politician from Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania. He served in both houses of the state legislature and represented Pennsylvania in the U.S. House from 1791 until 1799 and from 1803 to 1817. By the end of his career, he was the longest serving member of the House, and was the first to hold the honorary title "Father of the House". Findley was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 1789.[1]

Early years

William Findley was born in Ulster, Ireland and emigrated to Pennsylvania in 1763. In 1768, he bought a farm in Cumberland County, Pennsylvania,[2] where he married and started a family. Findley also worked for a time as a weaver.[3] He owned slaves as well.[4] In the American Revolution he served on the Cumberland County Committee of Observation, and enlisted as a private in the local militia, and rose to the rank of captain of the Seventh Company of the Eighth Battalion of Cumberland County Associators. In 1783 he moved his family across the Allegheny Mountains to Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania.

Public life

Upon arrival in Westmoreland County, Findley was almost immediately elected to the Council of Censors. On this Council, which was to decide whether the radical Pennsylvania Constitution of 1776 needed revision, he established himself as an effective supporter of what the "best people" considered the radical position in state politics.

In the following years Findley served in the Ninth through Twelfth General Assemblies and on the Supreme Executive Council. Findley was an early exponent of a political style in which candidates openly expressed their interests and proposals, as opposed to the "disinterested" style of governance many Founding Fathers envisioned.[5] In 1786 he was a critic of the Bank of North America, the nation's first central bank; he accused Robert Morris, the Continental Congress's Superintendent of Finance, of using the bank to enrich himself personally.[5] Findley also publicized the statement of fellow legislator Hugh Henry Brackenridge that "the people are fools" for opposing the bank, contributing to Brackenridge's defeat in the subsequent election.[6]

Findley was also a major opposition voice[7][8] in the Pennsylvania convention that ratified the federal Constitution and was a signer of the Minority Dissent.[9] Findley was regularly mocked during convention's debates by gentry who attempted to portray him an uneducated ' country hick '. At one point, Constitutional Convention delegate James Wilson and Pennsylvania Chief Justice Thomas McKean disputed one of Findley's statements about jury trials in Sweden; Findley returned two days later with William Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England and demonstrated that his reference had been correct.[10]

Findley was one of the leaders in the convention that, in 1789, wrote a new Constitution for Pennsylvania. As an Anti-Federalist, Findley wrote papers under the name of "An Officer of the Late Continental Army".

After serving in the Pennsylvania House of Representatives, he was elected to the Second Congress from the district west of the mountains in 1791. William Findley served in the Second through the Fifth congresses. A Jeffersonian Republican, Findley opposed the financial plans of Federalist Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton and supported the cause of states' rights.[11] As a voice of reason, in 1794 he helped to calm the passions of the Whiskey Insurrection. Unlike many Democratic-Republicans, he opposed slavery.[11]

After declining nomination to the Sixth Congress, he was elected to the Pennsylvania State Senate because he allowed his name to be placed on the local ticket to rally western support for Thomas McKean's campaign for governor.

Elected to the Eighth Congress, he served through the Fourteenth, the turbulent years of the Burr conspiracy, the embargo, and the War of 1812 as a strong supporter of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. He was known as "The Venerable Findley," and because he was the senior representative in years of service, he was in 1811 designated "Father of the House", the first man to be awarded that honorary title.[11] He died in his home along the Loyalhanna Creek on April 5, 1821, and is buried in Latrobe's Unity Cemetery.

Writings

- History of the Insurrection in the Four Western Counties of Pennsylvania in the Year M.DCC.XCIV (1794): With a Recital of the Circumstances Specially Connected Therewith, and an Historical Review of the Previous Situation of the Country. Philadelphia: Samuel Smith, 1796.

- Observations on the Two Sons of Oil. Pittsburgh: Engles, 1812.

References

- ↑ "William Findley". American Philosophical Society Member History. American Philosophical Society. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ↑ Wood, p. 218

- ↑ Wood, p. 17

- ↑ "Congress slaveowners", The Washington Post, 2022-01-19, retrieved 2022-07-11

- 1 2 Wood, p. 221

- ↑ Wood, pp. 219–20

- ↑ The Founders' Constitution

- ↑ The Junto Society

- ↑ Library of Congress: The Address and reasons of dissent of the minority of the convention, of the state of Pennsylvania, to their constituents.

- ↑ Wood, p. 222

- 1 2 3 Wood, p. 223

Bibliography

- Wood, Gordon S. (2009). Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789–1815. Oxford University Press.

Further reading

- Caldwell, John. William Findley: A Politician in Pennsylvania, 1783–1791. Gig Harbor, WA: Red Apple Publishing, 2000.

- Caldwell, John. William Findley From West of the Mountains, 1783–1791. Gig Harbor, WA: Red Apple Publishing, 2000.

- Caldwell, John. William Findley From West of the Mountains, 1791–1821. Gig Harbor, WA: Red Apple Publishing, 2002

- Eicholz, Hans L. "A Closer Look at 'Modernity:' The Case of William Findley and Trans-Appalachian Political Thought". In W. Thomas Mainwaring, ed., The Whiskey Rebellion and the Trans-Appalachian Frontier. Washington, Pennsylvania: Washington and Jefferson College, 1994, 57–72.

- Ewing, Robert (1919). "Life and Times of William Findley". Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine. 2: 240–51.

- Schramm, Callista (1937). "William Findley in Pennsylvania Politics". Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine. 20: 31–40.