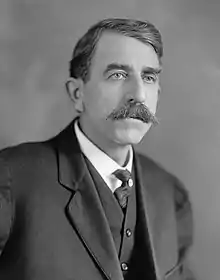

William H. Murray | |

|---|---|

Murray, c. 1930s | |

| 9th Governor of Oklahoma | |

| In office January 12, 1931 – January 15, 1935 | |

| Lieutenant | Robert Burns |

| Preceded by | William J. Holloway |

| Succeeded by | Ernest W. Marland |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Oklahoma | |

| In office March 4, 1913 – March 3, 1917 | |

| Preceded by | District created |

| Succeeded by | Tom McKeown |

| Constituency | At-large (1913–1915) 4th district (1915–1917) |

| 1st Speaker of the Oklahoma House of Representatives | |

| In office 1907–1909 | |

| Governor | Charles N. Haskell |

| Succeeded by | Ben Wilson |

| Personal details | |

| Born | William Henry Davis Murray November 21, 1869 Collinsville, Texas, U.S. |

| Died | October 15, 1956 (aged 86) Tishomingo, Oklahoma, U.S. |

| Resting place | Tishomingo City Cemetery 34°13′38.6″N 96°40′43.3″W / 34.227389°N 96.678694°W |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | Mary Alice Hearrell |

| Children | 5, including Johnston Murray |

| Parents |

|

| Profession | Teacher, lawyer |

William Henry Davis "Alfalfa Bill" Murray (November 21, 1869 – October 15, 1956) was an American educator, lawyer, and politician who became active in Oklahoma before statehood as legal adviser to Governor Douglas H. Johnston of the Chickasaw Nation. Although not American Indian, he was appointed by Johnston as the Chickasaw delegate to the 1905 Convention for the proposed State of Sequoyah. Later he was elected as a delegate to the 1906 constitutional convention for the proposed state of Oklahoma; it was admitted in 1907.

Murray was elected as a representative and the first Speaker of the Oklahoma House of Representatives after statehood. He also was elected as U.S. Representative (D-Oklahoma), and later as the ninth governor of Oklahoma from 1931 to 1935. During his tenure as governor in years of the Great Depression, he established a record for the number of times he used the National Guard to perform duties in the state and for declaring martial law at a time of unrest.

Early life and education

William Henry Davis Murray was born on November 21, 1869, in the town of Toadsuck, Texas (renamed "Collinsville" in the 1880s). He was born to Uriah Dow Thomas Murray, a farmer, and Bertha Elizabeth (Jones).[1] His mother died when he was two years old. His father remarried and moved the family to Montague, Texas. At the age of twelve, Murray left home.[2]

During most of Murray's adolescence, he worked on farms during the summer and attended public schools in the winter. Murray worked and studied hard, and was admitted to the College Hill Institute in Springtown, Texas. He graduated from College Hill with a teaching degree in 1889 and began teaching in a public school in Parker County, Texas.[1]

Murray became politically active and joined the Farmers' Alliance and the Democratic Party. He was a skilled orator and campaigned for James Stephen Hogg when the latter ran for Governor of Texas.[1]

Early career

Murray moved to Corsicana, Texas, where he founded a newspaper that survived for two years. During this time he ran for the state senate, but failed both attempts.[1] He moved to Fort Worth, Texas, where he worked as a writer for the Fort Worth Gazette. While at College Hill, Murray had taken an interest in law and "read the law" in Fort Worth. He passed the Texas bar exam in 1897, and first practiced law in Fort Worth, Texas.[1]

Indian Territory

In 1898, Murray moved to Tishomingo, the capital of the Chickasaw Nation in the Indian Territory (now eastern Oklahoma), where he started a law practice. Murray's legal knowledge and colorful personality brought him to the attention of Douglas H. Johnston, the Governor of the Chickasaw Nation, who appointed him as legal advisor. A year later, Murray married Johnston's niece Mary Alice Hearrell (see below). In addition to practicing law in Tishomingo, Murray began to learn farming and ranching.

He acquired his nickname "Alfalfa" around 1902 while working as a political operative for Palmer S. Moseley, gubernatorial candidate for the Oklahoma Territory. Murray frequently toured to give talks to local farmers about politics and farming. He often referred to a large tract of alfalfa which he cultivated. Arthur Sinclair, who heard one of his speeches, reported to the editor of the Tishomingo Capital-Democrat that he had just seen "Alfalfa Bill" deliver one of his finest speeches. The name stuck with Murray for the rest of his life.

Marriage and family

On July 19, 1899, Murray married Mary Alice Hearrell, niece of Chickasaw Governor Douglas H. Johnston.[1] They had five children together.[3] Their son, Johnston Murray, born in 1902, followed his father into politics and was elected as Governor of Oklahoma in 1950, serving 1951-1955.

States of Sequoyah and Oklahoma

Murray's relationship with the Chickasaw Governor Johnston benefited his political career. By 1903, American Indians of the Five Civilized Tribes were talking of seeking statehood for Indian Territory as an independent, Indian-controlled state, to be called the State of Sequoyah.

In 1905, the tribes organized a convention to draw up a state constitution. Governor Johnston appointed Murray to represent the Chickasaw at the convention in Muskogee. Of the six delegates at the convention, four were Native Americans; Murray and Charles N. Haskell were the only non-tribal, European Americans. The delegates drafted a constitution, which in a referendum was overwhelmingly approved by the voters of the Five Tribes.

Trying to avoid another state that might be dominated by Democrats (because of the Five Civilized Tribes' origin in the Southeast and their histories of slave-holding and alliance with the Confederacy in the Civil War), President Theodore Roosevelt, a Republican, opposed separate statehood for Sequoyah. Roosevelt insisted that the Indian and Oklahoma territories had to be admitted as one state – Oklahoma.

In response to Congress's passage of the Enabling Act in 1906, the people of the two territories held a joint convention. Murray was elected as the delegate for District 104, which included Tishomingo. At the convention in Guthrie, Murray worked closely with Robert L. Williams and again with Charles N. Haskell. They became lifelong friends and political allies.

.jpg.webp)

Due to his experience in Chickasaw politics, Murray was elected by the delegates in 1906 as the President of the Constitutional Convention. He kept Haskell close to him; one newspaper reported the latter was the "power behind the throne." Together, the two men controlled the convention, gradually shifting power away from the president and vice-president of the convention, Pleasant Porter (Creek) and Green McCurtain (Choctaw). The Oklahoma Constitution produced under their guidance was substantially based on elements of the Sequoyah Constitution.

The proposed constitution included white-supremacist and segregationist clauses strongly supported by Murray. President Roosevelt objected to these clauses and obtained their deletion before the constitution was submitted to Congress. The US Congress admitted Oklahoma to the Union as the 46th state on November 16, 1907.

Oklahoma politics

With the state constitution in place, elections were held in 1907 for offices of the new state government. Murray was elected as a state representative and, after being admitted to office, as the first Speaker of the Oklahoma House of Representatives.[4] His ally Charles Haskell was elected as the state's first governor.

As a speaker, Murray often opposed the progressive work of Kate Barnard, Commissioner of Charities and Corrections, and he pushed for Jim Crow laws similar to those in southern states to control blacks:

"We should adopt a provision prohibiting the mixed marriages of negroes with other races in this State, and provide for separate schools and give the Legislature power to separate them in waiting rooms and on passenger coaches, and all other institutions in the State ... As a rule they are failures as lawyers, doctors and in other professions...I appreciate the old-time ex-slave, the old darky – and they are the salt of their race – who comes to me talking softly in that humble spirit which should characterize their actions and dealings with the white man."

[5] Murray left the state legislature after one term and did not seek re-election in 1908.

In 1910, Murray ran for governor but lost in the Democratic primary. In 1912, Murray was elected as U.S. Representative from one of Oklahoma's three at-large seats. (Oklahoma had gained three seats in the 1910 Congressional apportionment but had not drawn up a new district map.) In 1914, he was elected to a second term from Oklahoma's 4th congressional district under the new map. In 1916, he was defeated for renomination as the Democratic candidate for this district.

In 1918, Murray again ran for governor and lost in the Democratic primary. He retired from politics and returned to private law practice in Tishomingo.

In 1924, Murray led a group of Oklahoma ranchers who formed a private colony in southeastern Bolivia. His son Johnston Murray joined him in this effort. He and his son stayed in Bolivia until 1929 when both returned to Oklahoma. Murray began a campaign for the Democratic nomination for governor in 1930.

Governor of Oklahoma

Murray won the Democratic nomination, and won the general election by almost 100,000 votes, the largest majority of any Oklahoma governor up to that time. His campaign slogan, at a time of the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl, railed against "The Three C's – Corporations, Carpetbaggers, and Coons."[6]

Murray was inaugurated as the ninth Governor of Oklahoma on January 12, 1931. He faced the harsh problems of the Great Depression. Under the previous Governor, William J. Holloway, the state government had accumulated a deficit of over $5,000,000 in its effort to encourage jobs and provide welfare. Mass unemployment, mortgage foreclosures, the deficit, and bank failures haunted Murray's administration. In 1931, the legislature appropriated $600,000 for emergency necessities. Through money collected from state employees, businessmen, and his own salary, Murray financed programs to feed Oklahoma's poor. No federal relief program had yet been instituted. Murray became a national leader for the victims of the Depression, and called for a national council for relief to be held at Memphis, Tennessee in June 1931.

During "Alfalfa Bill" Murray's campaign for governor, he promised to crack down on corruption and favoritism for the rich, to abolish half the clerk jobs at the State House, to appoint no family members, to reduce the number of state-owned cars from 800 to 200, never to use convict labor to compete with commercial labor, and not to abuse the power of pardon. Once in office, he appointed wealthy patrons and 20 of his relatives to high office, purchased more cars, used prisoners to make ice for sale and clean the capitol building, and violated all the other promises. When the State Auditor pointed out that 1,050 new employees had been added to the state payroll, Murray simply said, "Just damned lies." For each abuse of power, Murray claimed a mandate from "the sovereign will of the people".[7]

The government of Oklahoma faced failure, not only because of the massive deficit, but because many of Oklahoma's citizens could not pay their debts. To speed the collection of funds, at Murray's urging the Legislature created the Oklahoma Tax Commission. This three-member commission was responsible for the collection and administration of taxes, licenses and fees from all citizens. The new agency established safeguards against tax evasion and helped to stem the drain on the state's tax revenue.

Due to the severity of the depression, Murray relied on the Oklahoma National Guard to enforce the state's laws through the use of martial law. Murray did this in spite of impeachment threats from the Oklahoma Senate. During his tenure as governor, Murray called out the Guard and charged them with duties ranging from policing ticket sales at University of Oklahoma football games to patrolling the oil fields.

Murray also used the Guard during the "Toll Bridge War" between Oklahoma and Texas. A joint project to build a free bridge across the Red River on U.S. Highway 75 between Durant, Oklahoma and Denison, Texas turned into a major dispute when the Governor of Texas blocked traffic from entering his state on the new bridge. The Red River Bridge Company of Texas owned the original toll bridge and had a dispute over its purchase deal. Murray sent the Guard to reopen the bridge in July 1931. Texas had to retreat when lawyers determined that Oklahoma had jurisdiction over both banks of the river.

Murray used the Guard to reduce oil production in the hopes of raising prices. Because of the vast quantity of newly opened wells in Texas and Oklahoma, oil prices had sunk below the costs of production. Murray and three other governors met in Fort Worth, Texas to demand lower production. When the Oklahoma producers did not comply, on August 4, 1931, Murray called out the Guard, declared martial law, and ordered that some 3,000 oil wells be shut down.

By the end of his administration in 1935, Murray had used the National Guard on 47 occasions and declared martial law more than 30 times. As the state constitution prevented governors from succeeding themselves in office, Murray could not run for reelection and left office on January 15, 1935.

In 1933, Murray's longtime friend Charles Haskell died. Murray was very affected by this loss.

In 1932, Murray sought the Democratic nomination for President and ran in several primaries, but he did not win any. He received nearly 20 percent of the vote in Oregon. Huey Pierce Long, Jr., the former governor of Louisiana and U.S. senator, recalled visiting Murray in his hotel room at the 1932 Democratic National Convention in Chicago:

"Alfalfa Bill" was very gracious ... While we talked at length, he dwelt upon the virtue in the possible candidacies of everybody except Franklin Roosevelt and himself, even suggesting me as a candidate. He understood the favorite son game. I soon saw that I was fencing with a past master in politics. Had I listened to him very long, he would have been at work to make a favorite son candidate out of me. I was then moving Heaven and earth to keep down other favorite son candidates. ... Favorite son moves were the most dangerous things we had to fight. ...[8]

Murray initially supported President Franklin Roosevelt, but he later turned against the New Deal, as did other conservative Oklahoma politicians of that time.[9]

Later life and death

In 1938, Murray ran for governor, and lost in the Democratic primary.[9] Later that year, he tried to run for the United States Senate as an Independent, but his nominating petitions were filed late. In 1942, he ran for the Senate again and lost in the Democratic primary.

His wife, Mary Alice, died in Oklahoma City on August 28, 1938. Her body lay in state in the Oklahoma Capitol on the afternoon of August 29, 1938; she was the first woman to receive the honor. She was buried in Tishomingo the following day.[10]

After his retirement, Murray became widely known for his radical racist and conspiracy views. He wrote articles and books dealing with constitutional rights. In his books, Murray seemed to indicate his support for fascism. Murray supported Strom Thurmond's insurgent Dixiecrat bid for the presidency against Harry S. Truman and Thomas E. Dewey in 1948.

Murray's son, Johnston Murray, had followed his father into Democratic Party politics. The senior Murray administered the oath of office to his son in 1951 after he was elected as the state's fourteenth governor.

Murray did not live long past his son's governorship. He died on October 15, 1956, of a stroke and pneumonia.[2] He is buried in Tishomingo. Murray was considered the last surviving member of the Haskell Dynasty.

Legacy and honors

- Murray State College of Agriculture and Applied Science, is named in William Murray's honor. The community college is located in Tishomingo, Oklahoma.[11]

- Alfalfa County, Oklahoma and Murray County, Oklahoma are named in his honor.

State of the State speeches

- First State of the State Speech Archived October 9, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Second State of the State Speech Archived October 9, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Third State of the State Speech Archived October 9, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bryant Jr., Keith L. "Murray, William Henry David (1869–1956)". Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture – Oklahoma Historical Society. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- 1 2 Henry, pp. 10–11.

- ↑ Bryant Jr., Keith L. "Murray, William Henry David [Alfalfa Bill]". The Handbook of Texas Online – Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ↑ Henry, p. 11.

- ↑ Egan, Timothy. The Worst Hard Time: The Untold Story of Those Who Survived the Great American Dust Bowl. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co, 2006.

- ↑ Gould, Lewis L. (1980). Progressive Oklahoma: The Making of a New Kind of State by Danney Goble. The Journal of American History Vol. 67, No. 3. p. 714.

- ↑ Luthin, Reinhard (1954). American demagogues. Boston, Beacon Press. Retrieved August 21, 2022.

- ↑ Huey Pierce Long, Jr., Every Man a King: The Autobiography of Huey P. Long (New Orleans: National Book Club, Inc., 1933), pp. 304–305.

- 1 2 Henry, p. 14.

- ↑ Moore, Jesse E. "Alice Hearrell Murray". Chronicles of Oklahoma Vol. 17, No. 2. – Oklahoma Historical Society. Archived from the original on September 11, 2012. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- ↑ Rodden, Kirk A. "Murray State College". Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture – Oklahoma Historical Society. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

Sources

- State biography Archived October 9, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- William H. Murray Collection, Carl Albert Center, Oklahoma University

- Murray State College, Home Page

- "William H. Murray", Sooner State Genealogy

- Archived March 3, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Chronicles of Oklahoma. Henry, Robert H. Oklahoma Today. "Alfalfa Bill Murray." Volume 35, Number 4. July–August 1985. pp. 10–15. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- Luthin, Reinhard H. (1954). "Ch. 5: William H. Murray: 'Alfalfa Bill' of Oklahoma". American Demagogues: Twentieth Century. Beacon Press. ASIN B0007DN37C. LCCN 54-8428. OCLC 1098334.