William Henry Harrison Seeley | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | May 1, 1840 Topsham, Maine, US |

| Died | October 1, 1914 (aged 74) Dedham, Massachusetts, US |

| Buried | Evergreen Cemetery, Stoughton, Massachusetts |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service/ | Royal Navy |

| Rank | Ordinary Seaman |

| Unit | HMS Euryalus |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards | Victoria Cross |

William Henry Harrison Seeley, VC (May 1 1840 – October 1 1914)[1][lower-alpha 1] was an American who fought with the British Royal Navy during the Shimonoseki Campaign in Japan and was a recipient of the Victoria Cross (VC), the highest award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth forces. He was the first American-born recipient of the VC.[2][3]

Early life

Seeley was born on May 1, 1840, in Topsham, Maine to Dayton A. Seeley and Lucy J. Seeley (maiden name Johnston).[2][3] By the 1850s, he was either a longshoreman or dock labourer. A family squabble led to him running away at the age of 14, joining the compliment of a British merchant ship – the Salem – which was docked in Boston, Massachusetts at the time.[3][4]

After a voyage in which he saved the ship's carpenter from drowning by diving overboard after him, he found himself in Hong Kong. It was there that he jumped overboard after the skipper refused to allow him to buy firecrackers in Hong Kong so he could celebrate Independence Day. Soon after, he had spent all of his money. Seeing no other option, he decided to join the Royal Navy.[3]

Royal Navy service

Seeley, then approximately 22, joined the Royal Navy as an ordinary seaman on board the HMS Euryalus in 1862, which was then operating under the East Indies and China Station. The Euryalus was a fourth-rate wooden-hulled screw frigate. The Euryalus had landed in Hong Kong that year to contribute sailors to the 570-strong naval brigade assisting the Great Qing's Imperial Army during the Taiping Rebellion; this brigade often supported the Ever Victorious Army, commanded at the time by Charles George Gordon.[3]

The Euryalus left China for Japan later that year, where from August 15–17, 1863, he would see action during the Bombardment of Kagoshima.[3]

Background

Earlier that year, tensions were quickly rising following the order to expel barbarians, an Imperial edict issued by Emperor Kōmei which aimed to end Westernization in Japan. This edict was made in direct defiance of the Tokugawa shogunate, which had no plans to enforce the edict. The resulting power struggle between the shogunate and the Emperor turned from belligerent opposition between the many disgruntled daimyo's and the shogunate to open conflict.[3]

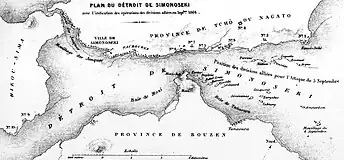

Daimyo Mōri Takachika of the Chōshū Clan supported the emperor,[3] declaring that, after the 10th day of the 5th month (according to the traditional Japanese calendar), all foreign ships traversing the Straits of Shimonoseki were to be fired upon without warning. The straits separated the islands of Honshū and Kyūshū, providing a passage between the Seto Inland Sea and the Sea of Japan.[5]

Following the deadline, the US merchant steamer SS Pembroke was attacked on June 25, 1863, by two European-built ships that belonged to Takachika's forces. The Pembroke was able to escape with only slight damage and no casualties.[6][7][8] The next day, the French aviso Kien Chan was attacked by artillery atop the bluffs surrounding the straits. The Kien Chan also managed to escape, suffering four casualties and a damaged engine.[7][9]

On July 11, despite warnings by the crew of the Kien Chan, the 16-gun Dutch warship Medusa sailed into the Straits. Her skipper, François de Casembroot, believed that, due to its firepower and the longstanding relations between the Netherlands and Japan, his ship would not be fired upon. Upon entering the strait, two blank shots were fired from one of the shore batteries, with this being answered by blanks fired from 8 of the Medusa's guns. The Medusa still didn't believe that they would be fired upon, especially seeing as the opposite shore was lined with junks. Soon after, Medusa was fired upon by the shore batteries and two vessels, to which the Medusa responded "with shot and shell". Due to the weight of fire against the Medusa from the ships and the batteries, the Captain determined that the best course of action would be to "make a dash" through the strait. The engagement lasted for an hour and a half, with the ship being hit 31 times, of which "17 pierced the hull" with the remainder passing through her rigging and funnel. The action left four dead and five wounded.[7][9]

On the morning of July 16, the US frigate USS Wyoming sailed into the straits under the sanction of Minister Robert H. Pruyn in an apparent swift response for the attack of the SS Pembroke. The Wyoming singlehandedly engaged the local fleet, sinking two ships and inflicting some 40 casualties; the Wyoming did however suffer significant damage in this action, with four dead and seven wounded - another would later die of his injuries.[6][7][10]

On July 20, the French Navy retaliated for the attack on the Kien Chan, sending the aviso Tancrède, and Admiral Maurice Berkeley's flagship, the HMS Semiramis. The compliment of 250 marines under Captain Benjamin Jaurès came ashore. Due to the overwhelming firepower of their forces, the soldiers that defended the guns only provided a token defence. They tossed most of the guns into the sea, along with other supplies left by the rebels. The French occupied the emplacements until July 24, destroying other nearby military camps and burning a local village.[7][10]

Diplomatic channels between all involved countries opened in attempts to reopen the straits. The British Minister to Japan, Sir Rutherford Alcock, spoke with his treaty partners Minister Robert Pruyn and Dutch Minister Dirk de Graeff van Polsbroek on the feasibility of a joint strike against Takachika and his forces.[7][11]

Soon after, a fleet of 15 British warships, including the Euryalus, four Dutch warships and a British regiment from Hong Kong was formed, sailing to Yokohama. In the meantime, Takachika requested additional time to respond to the treaty partners' demands. This was deemed to be unacceptable.[7]

Despite the prior retaliatory actions from the US and the French for the attacks on their merchant ships, another attack occurred in July 1864, when rebels fired upon the US steamer Monitor. The Monitor had left Hokkaido for Nagasaki while short on coal and water, expecting to be able to make it with a good wind. This was not to be however, with their fuel nearly exhausted they called in to the harbour at Fukugawa. The officials who boarded the vessel promised to report her requests for assistance, leaving on friendly terms. However, later that night, without any warning, a small battery near the town opened fire without warning. Before the Monitor could flee, she was fired upon by a large body of men who had assembled on the beach with gingals and muskets. Fortunately, the ship was partially protected by a strip of land that hindered the battery from gaining any reasonable accuracy. When the Monitor was sufficiently out of range, her crew returned fire with their two parrot rifles, of which two shells hit the town and set fires. No shells hit the body of men or the battery.[12]

This provoked outrage, even after a British squadron had presented an ultimatum to Takachika, threatening military force if the straits were not reopened.[7]

The Bombardment of Shimonoseki

On August 17, 1864, a squadron consisting of nine British, four Dutch (of which the Medusa was among them)[13], and three French warships, crewed by 3,000 sailors and a further 2,000 mainly British soldiers, all under the command of Admiral Sir Augustus Leopold Kuper of the Royal Navy, steamed out of Yokohama to open the straits. Kuper took command from the deck of the Euryalus.[7][14]

The only US warship in the area at the time was the sail-powered sloop-of-war USS Jamestown, which couldn't overcome the strong currents of the straits and thus couldn't join the expedition. As such, Minister Pruyn and then Captain Cicero Price chartered the steamer Ta-Kiang from Walsh, Hall and Company. Under the terms of the agreement, she was "to carry a landing party, and in every way to assist in the common object, but not to be under fire of the forts."[14][15] The Ta-Kiang would later assist the squadron by towing boats and receiving the wounded.[13] The full squadron of 17 ships had 388 guns and 7,542 men between them.[16]

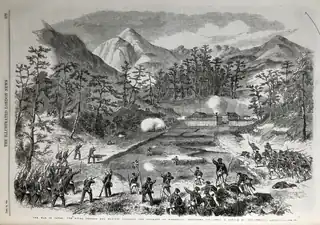

The battle took place between September 5–6 1864, with the bombardment taking place on September 5. Aimed at taking out the shore batteries, the fleet utilised their guns' range advantage, battering the shore batteries and fortifications from a relatively safe distance.[7] On Euryalus, Seeley watched as a 110-pounder breech-loading Armstrong gun, positioned on a pivot in the bows, engaged the Japanese forts at 4,800 yards. Soon, the batteries were silenced and the fleet ceased their bombardment.[3] The bombardment lasted for approximately one and a half hours.[15]

During the night the rebels had repaired some of their batteries, recommencing the battle at approximately six o'clock the next morning.[3][15] The allied fleet once again silenced the guns, preparing the ideal circumstances to begin landing soldiers on the coast in order to take the batteries and destroy their ammunition stores. In the afternoon, 1,900 soldiers (1,350 British, 350 French, and 200 Dutch) landed ashore and began their assault.[3][7] Seeley and his shipmates were assigned to the 3rd Company.[17]

Seeley volunteered to reconnoitre the enemy's positions, locating a stockade manned by the enemy. He was discovered by them, and, in the ensuing pursuit, he received an injury to his right arm by grape shot. Despite this injury, he would deliver a coherent report to his company commander, Second Lieutenant Frederick Edwards. Despite his injury, Seeley joined his fellow soldiers in the assault on the stockade.[3][17][18]

Seeing the British advance the rebels fell back to the stockade, which was manned by 300 men, seven light guns and protected by an 8ft palisade. At the head of the assault was the colour party. One of the colour sergeants was mortally wounded, while the second, petty officer Thomas Pride was hit in the left side of his chest by a musket ball.[18] Despite this injury, he refused to abandon midshipman Duncan Gordon Boyes who held the flag until both of them were ordered to the rear.[3] When they returned to the rear, it was discovered that the colour that Boyes had carried was "six times pierced by musket balls."[17]

Captain J. H. J Alexander was wounded in the ankle by a musket ball, falling to the ground.[3][18] Upon seeing this, Seeley said he immediately rushed to get him out of range. Seeley later said of the incident "I just picked him up like I had many a bag o’ tatters down in Sagadahoc county an’ pretty soon we was out o’ harms way, me an’ the captain." Seeley left Alexander in the care of a stretcher team, after which he re-joined the attack.[3]

Aftermath and Victoria Crosses

The London Gazette would later report on dispatches received from Kuper, stating "Since the conclusion of these operations I have satisfied myself, by personal examination, of the entire Straits, that no batteries remain in existence on the territory of the Prince of Choshiu, and thus the passage of the Straits may be considered cleared of all obstructions."[13]

Also in these dispatches, Captain J. H. J Alexander would report that "2nd. Lieutenant Frederick Edwards, commanding the third company, has called my attention to the intelligence and daring exhibited by William Seeley, ordinary seaman, in ascertaining the enemy's position, and afterwards, when wounded in the arm in the advance, continued to retain his position in the front."[17]

Pride, Boyes and Seeley would all be awarded the Victoria Cross for their courageous actions during the battle. They were presented the awards under much fanfare on September 22, 1865, at Southsea by Admiral Michael Seymour.[19] Seeley would leave the Royal Navy the next year, losing his medal twice between then and 1889.[3]

On the first occasion he had it stolen, with it being sent back to him anonymously from Whitehall. On the second occasion he had it stolen when he returned to East Boston.[3] It was discovered in a gutter by Mr. J. W. Grady, who at that time was just a young boy. At the time he had no idea what it was or what the significance of it was. He thought nothing of it for several years before learning what it was; as the owner couldn't be found, he kept hold of it despite several offers to buy it. Some 15 years after he found it, a friend of his showed him a copy of the Boston Evening News dated January 23 that had a page story about Seeley, titled "Only American Citizen to Win Victoria Cross".[20]

As the story had Seeley's name in it, he sent a message to Seeley at once to tell him how he found his Victoria Cross. In response, he received the following:[20]

"Dear Sir: I received your favor of the 6th and was surprised, for I supposed that I had lost the original cross in the docks in East Boston when I was going aboard a ship. I got a miniature cross in London which was the one I spoke of losing but it was returned to me once from the admiralty office and found at a curio shop. The one you have is no doubt the original one presented to me, which I won in 1864, which I would be pleased to have back once more, and will pay charges, if any, and come and see you next summer. I would be much pleased to meet you and show you returned friend you have had for so long."

Looking back on his life, he said: "Yes, sir, I’ve had my share o’ stirring times, I’ve done some things I aught – to say nothin’ o’ the things I hadn't ought to – but when all's said an’ done there's nothin’ I wouldn't do over again better’n saving old Bill Sharp carpenter o’ the Salem."[3]

Later life and death

Seeley later returned to Massachusetts, marrying Mary E. Moore on October 1 1900, with whom he ran a small farm on the line between Sharon and Stoughton until his wife's death at the farm.[2][4] Then, he moved in with his son, George G. Seeley, in Dedham, Massachusetts. He would later die here aged 74 on Thursday 1 October, 1914.[1][4] He was buried on October 4 that same year in Evergreen Cemetery, Stoughton near the plot of his sister, Bessie.[1][21] Seeley's name was never added to the foot marker of the grave, so the grave site went unrecognised until 2009 when funds were raised for the instalment of a memorial plaque.[21]

The last sighting of his Victoria Cross was in 1934 when it was in the possession of his granddaughter.[22]

Notes

- ↑ His birth date is variously described as being either May 1, 20 and 30 1840. His birth date of May 1, 1840 is on his headstone, whereas May 20 and 30, 1840 are variously described in newspapers of the time. The date on his headstone is used in this page.

References

- 1 2 3 "William Henry Harrison Seeley". www.memorialstovalour.co.uk. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

- 1 2 3 "William Henry Harrison Seeley - Veteran". www.seeley-society.net. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 MilitaryHistoryNow.com (April 14, 2020). "Meet William Seeley – The First American to Win Britain's Victoria Cross". MilitaryHistoryNow.com. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

- 1 2 3 "Won Victoria Cross - William Seeley of Dedham Gained Unusual Honor for an American". The Times Record. October 5, 1914. p. 2. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ↑ Culture, Japan-; History. (October 11, 2020). "The battle of Shimonseki in 1864 and the Maeda cannon battery". Japanese History and Culture. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- 1 2 "Wyoming I (Sloop of War)". public2.nhhcaws.local. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 GREAT BRITAIN, THE GREAT POWERS, AND THE SHIMONOSEKI INCIDENT, Roman Kodet

- ↑ Inuzuka, Takaaki; Laurie, Haruko (2021), "The Chōshū Five", Alexander Williamson, A Victorian chemist and the making of modern Japan, UCL Press, pp. 35–36, ISBN 978-1-78735-932-1, retrieved January 16, 2024

- 1 2 "Japan Commercial News Extra". Chicago Daily Tribune. October 6, 1863. p. 1. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- 1 2 Lee, Edwin B. (1985). "Robert H. Pruyn in Japan, 1862–1865". New York History. 66 (2): 129. ISSN 0146-437X.

- ↑ Lee, Edwin B. (1985). "Robert H. Pruyn in Japan, 1862–1865". New York History. 66 (2): 131–133. ISSN 0146-437X.

- ↑ "CHINA (FROM OUR OWN CORRESPONDENT)". The Times. September 28, 1864. p. 8. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- 1 2 3 "Page 5471 | Issue 22913, 18 November 1864 | London Gazette | The Gazette". www.thegazette.co.uk. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

- 1 2 Lee, Edwin B. (1985). "Robert H. Pruyn in Japan, 1862–1865". New York History. 66 (2): 133. ISSN 0146-437X.

- 1 2 3 "Ta-Kiang (Screw Steamer)". public1.nhhcaws.local. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

- ↑ Lee, Edwin B. (1985). "Robert H. Pruyn in Japan, 1862–1865". New York History. 66 (2): 134. ISSN 0146-437X.

- 1 2 3 4 "No. 22913". The London Gazette. November 18, 1864. p. 5471.

- 1 2 3 "Page 5472 | Issue 22913, 18 November 1864 | London Gazette | The Gazette". www.thegazette.co.uk. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ↑ "The Victoria Cross". The Times. September 23, 1865. p. 25. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- 1 2 "Victoria Cross Lost 15 Years Returned to Owner, William Seeley". The Barre Daily Times. February 8, 1904. p. 1. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- 1 2 "WILLIAM SEELEY VC". www.victoriacross.org.uk. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ↑ "WILLIAM SEELEY VC". www.victoriacross.org.uk. Retrieved January 15, 2024.