| William of Bures | |

|---|---|

| Prince of Galilee | |

| Reign | 1119/20–1143/44 1153–c. 1158 (?) |

| Predecessor | Joscelin of Courtenay Simon of Bures (?) |

| Successor | Elinand Walter of Saint Omer (?) |

| Died | 1143/44 or c. 1158 |

| Spouse | Agnes Ermengarde of Ibelin (?) |

| Issue | Elinand (?) Eschiva of Bures (?) |

| Father | Hugh of Crécy (?) |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

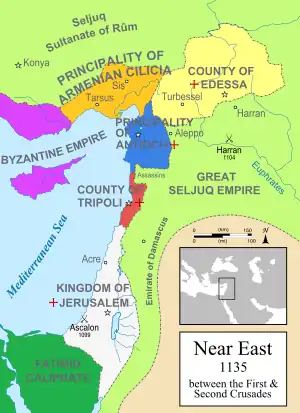

William of Bures (died before the spring of 1144, or around 1157) was Prince of Galilee from 1119 or 1120 to his death. He was descended from a French noble family which held estates near Paris. William and his brother, Godfrey, were listed among the chief vassals of Joscelin of Courtenay, Prince of Galilee, when their presence in the Holy Land was first recorded in 1115. After Joscelin received the County of Edessa from Baldwin II of Jerusalem in 1119, the king granted the Principality of Galilee (also known as Lordship of Tiberias) to William. He succeeded Eustace Grenier as constable and bailiff (or regent) in 1123. In his latter capacity, he administered the kingdom during the Baldwin II's captivity for more than a year, but his authority was limited.

William was the most prominent member of the embassy that Baldwin II sent to France in 1127 to start negotiations about the marriage of his eldest daughter, Melisende, and Fulk V of Anjou. William escorted Fulk from France to Jerusalem in 1129. Fulk, who succeeded Baldwin II in 1131, dismissed his father-in-law's many officials, but William retained the office of constable. Although most historians agree that he died in 1143 or 1144, Hans Eberhard Mayer says that Melisende forced William into exile after Fulk died in 1143, but he regained Galilee from her son, Baldwin III of Jerusalem in 1153.

Early life

Albert of Aix recorded that William's brother, Godfrey, was "of the land of the city of Paris".[1] His statement evidence that William and Godfrey of Bures came from Bures-sur-Yvette.[2] Jonathan Riley-Smith identifies William as a son of Hugh of Crécy, and thus a great-grandson of Guy I of Montlhéry.[3] The descendants of Montlhéry and his wife, Hodierna of Gometz, played preeminent role in the history of the Kingdom of Jerusalem.[4] Both Baldwin of Le Bourcq (who was the second king of Jerusalem) and Joscelin of Courtenay (who was William's predecessor in Galilee) were their grandsons.[4][3] Historian Hans Eberhard Mayer emphasizes that William's ancestry has not been convincingly verified and his relationship to the Montlhéry clan is only an assumption.[4]

Mayer associates William with a William of Buris who was listed among the patrons of the confraternity that Hugh, Abbot of St. Mary of the Valley of Jehosaphat, established around 1104.[2] If the identification is valid, William must have spent some time in Southern Italy before coming to the Kingdom of Jerusalem, because the list mentioned the benefactors who had come from Southern Italy.[2] The list, continues Mayer, also evidences that William was born before 1090, because he must have been of age when he joined the confraternity.[2] Riley-Smith writes that William settled in the Holy Land only in 1114, "presumably to expiate some act of violence perpetrated during the unsuccessful rebellion of a league of castellans against the king of France".[5]

The Gesta episcoporum Cennomannensium ("Deeds of the Bishops of Le Mans") recorded that William had come to the Holy Land "as an act of penance".[5][4] His presence in the kingdom was first documented in 1115, when he was listed among the principal vassals of Joscelin of Courteney, Prince of Galilee.[2] Joscelin made a plundering raid against a Bedouin tribe in the spring of 1119.[6] William and his brother accompanied him.[6] Joscelin divided his army to encircle the tribe's camp on the river Yarmouk, making the Bures brothers the commander of one of the corps.[6] When they were approaching the Bedouins' camp, they were ambushed by the Bedouins.[6] William could escape, but Godfrey died fighting most of their retainers were captured.[6]

Prince of Galilee

Baldwin's baron

.jpg.webp)

Baldwin II of Jerusalem gave the County of Edessa to Joscelin in August or September 1119.[7][8] Before 15 January 1120, the king granted Joscelin's former principality to William,[9][10][2] who thus seized one of the largest fiefs in the kingdom.[4] William was one of the four or five secular lords to attend the Council of Nablus on 16 January 1120.[11] The council confirmed the right of the clergy to control the collection of the tithes and ordered the persecution of sexual misdemeneanours.[12][13] William donated estates in Lajjun and near Tiberias to the hospital of the Abbey of St. Mary of the Valley of Jehosaphat on 1 February 1121.[14]

Balak ibn Bahram, the Artuqid ruler of Suruç and Mardin, captured Baldwin II on 18 April 1123.[15] The Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem, Warmund of Picquigny, convoked an assembly which elected Eustace Grenier constable and bailiff to administer the kingdom, but Grenier died on 15 May or June.[16][17] The council again assembled and appointed William to both offices.[18] Meanwhile, a Venetian fleet had landed at the Holy Land, carrying 15,000 soldiers.[19] The patriarch, William and Pagan, the chancellor of Jerusalem, concluded a treaty with the Doge of Venice, Domenico Michiel on behalf of the king.[18][17] In accordance with Baldwin's previous promises to the Venetians, the treaty—the so-called Pactum Warmundi—granted privileges to them in both the Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Principality of Antioch in exchange for their assistance to besiege either Tyre or Ascalon.[17][20] The barons of the realm could not decide which town should be attacked, thus their debate was settled by lot in favor of Tyre.[21]

The crusaders and the Venetians laid siege to Tyre on 16 February 1124.[21] Patriarch Warmund was acknowledged as the supreme commander of the army.[22] The defenders of the town urged Toghtekin, Atabeg of Damascus, to attack the crusaders, but he only marched as far as Banyas.[23] The patriarch appointed William and Pons, Count of Tripoli, to launch a military expedition against Toghtekin, but he avoided any engagements and returned to Damascus.[23][24] The crusaders captured Tyre on 7 or 8 July.[21]

Baldwin II won his freedom in late August 1124, but he returned to Jerusalem only on 3 April 1125.[24][25] He had not fathered a son and decided to give her eldest daughter, Melisende, in marriage to an influential European ruler.[26] After consulting with his barons, he chose Fulk V of Anjou.[27] He appointed William and Guy I Brisebarre to lead an embassy to Anjou and to start negotiations with Fulk.[26][28] William was also authorized to pledge that Fulk could marry Melisende in fifty days after he came to the Holy Land and the marriage would secure his right to succeed Baldwin on the throne.[26]

The embassy departed in the autumn of 1127.[26][20] Fulk accepted the offer and took the Cross in token of his decision to go to the Holy Land at Le Mans on 31 May 1128.[26] William and Brisbarre accompanied Fulk from France to the Kingdom of Jerusalem in the spring of 1129.[29] They landed at Acre in May.[29] Fulk married Melisende before 2 June.[30] In the same year, William donated the village of St Job (at present-day Dayr Ayyub) to the Abbey of St. Mary of the Valley of Jehosaphat, but secured the right of his nephew, William (who had become a monk) to the revenues from the leasing out of the estate.[31]

Fulk's supporter

Baldwin II died on 21 August 1131.[32] In accordance with his last will, Fulk and Melisende were jointly crowned on 14 September, but Fulk wanted to secure the government for himself and to reduce his wife to background.[33][34][35] He replaced the castellans of the royal castles with his own retainers from Anjou and marginalized Baldwin II's most barons.[36] In contrast with them, William retained the office of constable during Fulk's reign.[28] He witnessed Fulk's three authentic charters as the first of the secular barons.[37] The king confirmed Willim's donation to the canons of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in 1132.[38] William accompanied Fulk during his unsuccessful campaign against Imad ad-Din Zengi, Atabeg of Mosul, who had laid siege to Montferrand (at present-day Baarin in Syria) in July 1137.[37][39]

Most historians agree that William died between September 1143 and April or May 1144.[28] They base their view on a memorandum that Guy, Abbot of St. Mary of the Valley of Jehosaphat, compiled in the spring of 1146.[28] The abbot complained that Robert I, Archbishop of Nazareth, had cunningly installed his chaplain in the abbey's church at Lajjun after the news of Pope Innocent II's death reached the Holy Land (most probably in the spring of 1144).[28] The archbishop also instructed his chaplain to say Mass for William's soul.[28][40] Mayer emphasizes that the memorandum does not prove that William was actually dead, because the document does not refer to his death and a Mass could also be said for the benefit of a living person.[41]

William II

According to a widespread scholarly theory, two rulers of Galilee were named William.[28] However, William of Tyre mentioned only one William when listing the princes of Galilee in his chronicle.[42] Likewise, Walter of Saint Omer, who was Prince of Galilee from 1159 to 1174, regarded unnecessary to clarify which of the two assumed Williams had made the grant to the Holy Sepulchre in 1132 when confirming William's donation.[42] On the other hand, a Willelmus Tiberiadis (or William of Tiberias) witnessed a charter that Constance of Antioch issued at Latakia in 1151.[42] The Principality of Galilee was also known as the Lordship of Tiberias around that time.[28]

Taking into account these documents, Mayer concludes that there was only one Prince William of Galilee and "William II" was actually identical with William I.[42] He proposes that Melisende forced William to leave the Kingdom of Jerusalem shortly after Fulk died in November 1143.[41] According to Mayer, Melisende, who ruled the kingdom for years after her husband's death,[43] gave Galilee to Elinand (whom Mayer supposes to have been related to a former prince, Hugh of Fauquembergues).[44] William, Mayer continues, regained Galilee in 1153, shortly after Fulk and Melisende's son, Baldwin III of Jerusalem, started to rule independently of his mother.[45] William was last mentioned in a charter issued on 4 October 1157.[45]

Family

William had a wife, named Agnes in 1115, but she must have died shortly thereafter, because she was not mentioned in other documents.[46] William and Agnes obviously had no children, because he named his nephews, Elias and William as his heirs in 1126.[38] His nephew and namesake became a monk at the Abbey of St. Mary of the Valley of Jehosaphat in or before 1129.[38] William's 1129 charter to the same abbey was witnessed by Ralph of Issy.[38] Ralph and a Simon were identified as William's nephews in 1132.[38] Based on the four documents, Mayer concludes that William disinherited Elias and William in favor of Ralph of Issy and Simon shortly after he returned from France in 1129.[38] Historian Martin Rheinheimer associates Elias with Elinand who succeeded William in 1144.[42] In contrast with both Mayer and Rheinheimer, historian Malcolm Barber says that Elinand was William's son.[47]

Mayer proposes that Ermengarde of Ibelin (a sister of Hugh of Ibelin) who was styled as the lady of Tiberias in 1155 was William's second wife.[42] Historian Pirie-Gordon identified her as Elinand's wife, while Rheinheimer wrote that she was the wife of William II of Bures (William's nephew),[48] but Peter W. Edbury accepts Mayer's view.[49] Mayer also says that Ermengarde gave birth to Eschiva of Bures who was William's heiress in 1158.[50]

References

- ↑ Mayer 1977, p. 299.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mayer 1994, p. 157.

- 1 2 Riley-Smith 1997, pp. 169–170, Appendix II (B: The Montlhery Clan).

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mayer 1989, p. 15.

- 1 2 Riley-Smith 1997, p. 172.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Runciman 1989, p. 147.

- ↑ Barber 2012, pp. 128, 360.

- ↑ Lock 2006, pp. 33–34.

- ↑ Runciman 1989, p. 156.

- ↑ Riley-Smith 1997, pp. 174–175.

- ↑ Barber 2012, pp. 129–130.

- ↑ Lock 2006, p. 34.

- ↑ Barber 2012, pp. 130–131.

- ↑ Pringle 1993, pp. 3–4.

- ↑ Barber 2012, p. 138.

- ↑ Runciman 1989, pp. 162–163, 166.

- 1 2 3 Barber 2012, p. 140.

- 1 2 Runciman 1989, p. 166.

- ↑ Barber 2012, pp. 139–140.

- 1 2 Lock 2006, p. 37.

- 1 2 3 Barber 2012, p. 141.

- ↑ Runciman 1989, p. 169.

- 1 2 Runciman 1989, p. 170.

- 1 2 Barber 2012, p. 142.

- ↑ Lock 2006, p. 38.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Barber 2012, p. 145.

- ↑ Barber 2012, pp. 145–146.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Mayer 1994, p. 158.

- 1 2 Runciman 1989, p. 178.

- ↑ Barber 2012, p. 146.

- ↑ Pringle 1993, p. 239.

- ↑ Lock 2006, p. 40.

- ↑ Lock 2006, p. 41.

- ↑ Barber 2012, p. 155.

- ↑ Mayer 1989, p. 1.

- ↑ Mayer 1989, p. 4.

- 1 2 Mayer 1989, p. 12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mayer 1989, p. 16.

- ↑ Lock 2006, p. 43.

- ↑ Pringle 1993, p. 4.

- 1 2 Mayer 1994, pp. 158–159.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mayer 1994, p. 159.

- ↑ Barber 2012, p. 174.

- ↑ Mayer 1994, pp. 159–160.

- 1 2 Mayer 1994, p. 160.

- ↑ Mayer 1994, pp. 161–162.

- ↑ Barber 2012, p. 177.

- ↑ Mayer 1994, pp. 162, 165.

- ↑ Edbury 1997, p. 5.

- ↑ Mayer 1994, p. 163.

Sources

- Barber, Malcolm (2012). The Crusader States. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11312-9.

- Edbury, Peter W. (1997). John of Ibelin and the Kingdom of Jerusalem. The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-703-0.

- Lock, Peter (2006). The Routledge Companion to the Crusades. Routledge. ISBN 9-78-0-415-39312-6.

- Mayer, Hans Eberhard (1977). Bistümer, Klöster und Stifte im Königreich Jerusalem. Hiersemann. ISBN 3-7772-7719-3.

- Mayer, Hans Eberhard (1989). "Angevins versus Normans: The New Men of King Fulk of Jerusalem". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 133 (1): 1–25. ISSN 0003-049X.

- Mayer, Hans Eberhard (1994). "The crusader principality of Galilee between Saint-Omer and Bures-sur-Yvette". In Gyselen, R. (ed.). Itinéraires d'Orient: Hommages à Claude Cahen. Groupe pour l'Étude de la Civilisation du Moyen-orient. pp. 157–167. ISBN 978-2-9508266-0-2.

- Pringle, Denys (1993). The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: A Corpus: Volume 2, L-Z (excluding Tyre). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-39037-0.

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan (1997). The First Crusaders, 1095-1131. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-59005-1.

- Runciman, Steven (1989). A History of the Crusades, Volume II: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East, 1100-1187. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-06163-6.