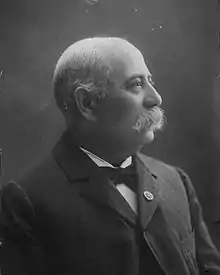

William Lovenstein | |

|---|---|

| |

| President pro tempore of the Senate of Virginia | |

| In office December 4, 1895 – December 26, 1896 | |

| Preceded by | John L. Hurt |

| Succeeded by | Henry T. Wickham |

| Member of the Virginia Senate from the 35th district | |

| In office December 7, 1881 – December 26, 1896 | |

| Preceded by | William W. Henry |

| Succeeded by | Beverley B. Munford |

| Member of the Virginia House of Delegates from Richmond City | |

| In office December 3, 1879 – December 7, 1881 | |

| Preceded by | Samuel H. Pulliam |

| Succeeded by | T. Wiley Davis |

| Personal details | |

| Born | William Lovenstein October 8, 1840 Laurel, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | December 26, 1896 (aged 56) Richmond, Virginia, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | Dora Wasserman |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Confederate States |

| Branch/service | Confederate States Army |

| Years of service | 1861–1864 |

| Rank | First sergeant |

| Unit | Richmond Light Infantry Blues |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

William Lovenstein (October 8, 1840 – December 26, 1896) was a businessman and Democratic politician who served in both houses of the Virginia General Assembly. Lovenstein served in the Virginia Senate for fifteen years before his death and became its president pro tempore during its 1896 session. He remains one of the highest ranking Jewish politicians in Virginia history.[1]

Early and family life

The firstborn son of Solomon Lovenstein (1815-1873) and his wife, the former Mary Wasserman (1814-1896), was born near Laurel, Henrico County, Virginia. His parents had emigrated from the cattle-trading town of Illereichen in Bavaria, as had the Myers and Hirsch families which also became prominent in (nearby) Richmond (85% of Jews emigrating to Richmond between 1835 and 1860 came from Germany; and so many emigrated from the Jewish communities of Illereichen and nearby Altenstadt that their Bavarian community was 40% smaller in 1854 than 1834).[2] He had two brothers—Isidore (1842-1913) and Joseph (1848-1924) who would both move to Savannah, Georgia after the war—and four sisters (of whom Fannie Lovenstein Harris (1851-1916) moved to Cleveland, Ohio and Isabella Lovenstein Wasserman (1844-1921) moved to Philadelphia).[3] In 1850, his father (a merchant and market gardener) also became the local postmaster at the Erin Shades train stop near modern Glen Allen. The family owned enslaved people in both the 1850 and 1860 censuses.[4][5]

Lovenstein married Dora Wasserman in Richmond on October 14, 1863.[6] During their more than five decades of marriage, they had several children, including son Solomon (b. 1875) and daughters Irene (b. 1864), Rosa (b. 1866), Flora (b. 1868), Hattie (b. 1870), Stella (b. 1872), Miriam (b. 1877) and Etta (b. 1879).[7]

Military service

Even before the American Civil War, Lovenstein was active in the Richmond Light Infantry Blues, as were Capt. Ezekiel Levy and the six sons of Myer Angle, the first president of Beth Ahabah synagogue (whose rabbi Rev. Maximilian Michelbacher at least one author thought had the fervor of a Confederate military chaplain).[8] The "Blues" were Richmond's most distinguished militia company, and Virginia's oldest, having been formed in 1789 and given the nickname due to uniforms adopted in 1793. The Blues also responded to slave revolts beginning in 1800, including Nat Turner's revolt in 1831. In 1851 it was reorganized as company E of the First Virginia Regiment, and in 1859 sent to Harpers Ferry to keep order after the failed raid at Harper's Ferry.[9] The other Richmond militia company with many Jewish members was the Richmond Grays, who marched to Charles Town in late 1859 to prevent any attempt to rescue John Brown before his execution for the failed raid.[10]

As the American Civil War began, Lovenstein enlisted for service in the Confederate States Army. On April 23, 1861, just days after Governor Letcher called for troops, the "Blues" had voted to secede from the First Virginia, and asked to be attached "to some new Regiment to be placed under the command of a former United States officer who is a tactician and disciplinarian".[11] They were instead sent by train to Fredericksburg with the First Virginia, and drilled extensively, as well as participated in several false alarms about Federal gunboats in the Potomac River near Aquia. On June 7, Blues Captain Obediah Jennings Wise (editor of the Richmond Enquirer and son of Virginia Governor turned Confederate General Henry A. Wise) told his troops that he had requested a transfer to his father's command in western Virginia. The Blues unanimously voted to follow him, and they left Marlboro Point by train to Richmond on June 10, 1861, reached Lewisburg on June 17, 1861 and were sworn into Virginia's 46th Infantry in the Confederate Army. Though "Wise's Legion" would grow to about 2700 men by July, and the Blues were the brigade's best-trained company, the Legion was responsible for a huge area, and General Wise also feuded with General Floyd. The 46th's first colonel, James Lucius Davis, really acted as Wise's cavalry commander, so the unit was actually led by Lt.Col. John H. Richardson, who had started street car companies in Cincinnati and St. Louis before the war, as well as risen to the rank of colonel of the 179th Virginia militia and written an infantry manual adopted by the Confederate government.[12] Wise sent the 46th on many long marches, and the unit endured both a measles epidemic and a minor mutiny by August. On September 25, President Jefferson Davis removed General Wise from command and ordered him back to Richmond. The Blues would be recalled to the Confederate capitol by December, then the 46th was again placed under General Wise's command and sent in January 1862 to defend Roanoke Island, a crucial part of Norfolk's defenses. However, while General Wise suffered from pleurisy and was confined to his tent ashore, Federal forces won the Battle of Roanoke Island. Though casualties were relatively low, Capt. Wise was among the 23 Confederates killed and Lovenstein among the many captured on February 6, 1862. He was paroled from North Carolina on February 21. His younger brother Isidore also served in the Confederate Army (in the 12th Virginia Infantry) and would rise to sergeant before being restricted to clerical duties based on a wound received at the Battle of Williamsburg in May 1862. William Lovenstein had many health issues, even early in his service as the unit was sent to western Virginia, and spent most of 1863 and 1864 as a clerk in the Medical Purveyor's Office until receiving a disability discharge on November 24, 1864 due to a leg ulcer which failed to heal.[13] In 1864, Lowenstein had re-enlisted in Richmond's reserves as a sergeant.

Richmond civil leader and Virginia legislator

In the 1860 census, Lovenstein lived with his father's family and was listed as a clerk.[14] In the 1870 federal census, Lovenstein was characterized as a "mumble manufacturer", and lived with his wife in Richmond.[15] A decade later, he was a "bookkeeper", and continued to live in the capitol with his growing family.[7] Meanwhile, his parents, three sisters and brother Isidore had moved to rural Newtown, King and Queen County after the war, where Solomon Lovenstein became a "sumac manufacturer" and Isidore ran a grocery and dry goods store.[16]

Lovenstein's legislative service (which traditionally in Virginia was part-time) began immediately after Virginia voters ratified most of the work product of the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1868, except the bar against former Confederates holding political office. Lovenstein won election as one of nine delegates representing Richmond City and Henrico County, alongside A. Bodeker, A.M. Keiley, L.H. Frayser, J.S. Atlee, J.B. Crenshaw, George K. Gilmer, Stephen Mason and John H. Guy.[17] Although Richmond City and Henrico County were split in the next election, Lowenstein continued to win re-election several times, this time as one of Richmond City's delegates, and served alongside James H. Dooley, John Thompson Brown, William S. Gilman and R.T. Daniel (by 1874, Joseph R. Anderson and Robert Ould replaced Brown and Daniel as his colleagues).[18] Although Lovenstein failed to make the initial cut for the General Assembly of 1875-1877, by the time the House of Delegates convened for the term's second session, Lovenstein replaced W.W. Crump, and so was seated alongside James H. Dooley and William S. Gilman (Charles U. Williams and W.P.M. Kellam also replaced Anderson and Ould). Lovenstein did not win any legislative seat in the 1878 session, but in 1879 again represented Richmond City, this time alongside John Hampden Chamberlayne, James Lyons Jr. and S. B. Witt.[19] Lovenstein won election to the Virginia Senate in 1881, representing Richmond City as well as Henrico County, and won re-election several times before his death in office, serving the two-senator district alongside first Henry A. Atkinson Jr. (1881-1885), then J. Taylor Ellyson (1885-1889), and finally Conway R. Sands (1889-1896).[20] In his final term, fellow senators elected him their president pro tempore, to lead them when Virginia's lieutenant governor did not chair that chamber.

The postwar state constitution for the first time mandated public schools, and Lovenstein served as president of Richmond's School Board, which as in the rest of the state segregated pupils (and teachers) by race. After becoming a state legislator, Lovenstein sponsored a bill requiring all Black teachers to attend summer "normal" schools (teacher-training).[21] He also sponsored a bill to care for the Black insane, and in 1887 helped launch a new library association for Richmond (and served as a director and later treasurer).[22] When Russian Jews began emigrating to the United States in significant numbers late in the century, Lovenstein became secretary of the relief committee, with Moses Milhiser of Beth Ahabah as president and banker Edward Cohen as the committee's treasurer.[23] Lovenstein was the Beth Ahabah synagogue's secretary in 1891, when it sought a new rabbi. In a letter to the ultimately successful candidate, Nathan Calisch, he characterized the congregation as conservative and opposed to Sunday services, advising that the board of managers sought a congregational leader who would have the community's respect (and president Milhiser stressed that the candidate must not only be a scholar but a native-born American).[24] Lovenstein also served as officer of one of the three Richmond lodges of B'nai B'rith, and as a delegate to the 1890 national B'nai B'rith conference held in Richmond.[25] He was also active in the Elks Club and the Royal Arcanum.[26]

Death

Lovenstein suffered heart and kidney issues in his final years in office, and died of heart failure at his Richmond home on December 26, 1896.[27]

References

- ↑ Myron Berman, Richmond's Jewry: Shabbat in Shockoe 1769-1976 (University Press of Virginia 1980)

- ↑ Berman p. 135

- ↑ 1860 U.S. Federal Census for Western Subdivision, Henrico County, p. 43 of 174.

- ↑ 45 and 17 year old Black women, 35 and 17 year old Black men and a 14 year old Black girls in the 1850 U.S. Federal Census for Western Subdivision, Henrico County, Slave Schedule p. 27 of 40

- ↑ a 30 year old Black woman, Black boys aged 12 and 3, as well as Black girls aged 8 and 5 years old in the 1860 U.S. Federal Census for Western Subdivision, Henrico County, Slave Schedule p. 18 of 52

- ↑ Virginia marriage record on ancestry.com

- 1 2 1880 U.S. Federal Census for District 82, Richmond, Virginia p. 49 of 53

- ↑ Berman pp. 176-178

- ↑ Darrell L. Collins, 46th Virginia Infantry (Lynchburg: H.E. Howard Inc. Virginia Regimental History Series 1992) pp. 4-5

- ↑ Berman p. 176

- ↑ Collins p. 4

- ↑ Collins p. 13

- ↑ Collins, p. 124

- ↑ 1860 U.S. Federal census for Western Subdivision, Henrico County, Virginia p. 43 of 174

- ↑ 1870 U.S. Federal census for Richmond Madison Ward, Henrico County, Virginia p. 64 of 296

- ↑ 1870 U.S. Federal Census for Newtown, King and Queen County, Virginia family 126 p. 18 of 67

- ↑ Cynthia Miller Leonard, The Virginia General Assembly 1619-1978 (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1978) p. 509.

- ↑ Leonard pp. 514, 518

- ↑ Leonard p. 530

- ↑ Leonard pp. 536, 540, 544, 548, 552. 556, 560, 564

- ↑ Berman p. 235

- ↑ Berman p. 237

- ↑ Berman p. 221

- ↑ Berman pp. 245-246

- ↑ Berman pp. 228, 257-258

- ↑ Berman p. 380 n.78 citing Richmond Times April 14, 1887 and December 7, 1886

- ↑ Virginia death certificate

External links

- William Lovenstein at The Virginia Elections and State Elected Officials Database Project, 1776-2007