William Ramsay | |

|---|---|

Ramsay in 1904 | |

| Born | 2 October 1852 Glasgow, Scotland |

| Died | 23 July 1916 (aged 63) High Wycombe, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | University of Glasgow (1866–69) Anderson's University,now University of Strathclyde Glasgow (1869)[1] University of Tübingen (PhD 1873) |

| Known for | Discovering noble gases |

| Awards | Leconte Prize (1895) Barnard Medal for Meritorious Service to Science (1895) Davy Medal (1895) Longstaff Prize (1897) Nobel Prize in Chemistry (1904) Matteucci Medal (1907) Elliott Cresson Medal (1913) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Chemistry |

| Institutions | University of Glasgow (1874–80) University College, Bristol (1880–87) University College London (1887–1913) |

| Doctoral advisor | Wilhelm Rudolph Fittig |

| Doctoral students | Edward Charles Cyril Baly James Johnston Dobbie Jaroslav Heyrovský |

Sir William Ramsay KCB FRS FRSE (/ˈræmzi/; 2 October 1852 – 23 July 1916) was a Scottish chemist who discovered the noble gases and received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1904 "in recognition of his services in the discovery of the inert gaseous elements in air" along with his collaborator, John William Strutt, 3rd Baron Rayleigh, who received the Nobel Prize in Physics that same year for their discovery of argon. After the two men identified argon, Ramsay investigated other atmospheric gases. His work in isolating argon, helium, neon, krypton, and xenon led to the development of a new section of the periodic table.[2]

Early years

Ramsay was born at 2 Clifton Street[3] in Glasgow on 2 October 1852, the son of civil engineer and surveyor, William C. Ramsay, and his wife, Catherine Robertson.[4] The family lived at 2 Clifton Street in the city centre, a three-storey and basement Georgian townhouse.[3] The family moved to 1 Oakvale Place in the Hillhead district in his youth.[5] He was a nephew of the geologist Sir Andrew Ramsay.

He was educated at Glasgow Academy and then apprenticed to Robert Napier, a shipbuilder in Govan.[6] However, he instead decided to study Chemistry at the University of Glasgow, matriculating in 1866 and graduating in 1869. He then undertook practical training with the chemist Thomas Anderson and then went to study in Germany at the University of Tübingen with Wilhelm Rudolph Fittig where his doctoral thesis was entitled Investigations in the Toluic and Nitrotoluic Acids.[7][8][9]

Ramsay went back to Glasgow as Anderson's assistant at Anderson College. He was appointed as Professor of Chemistry at the University College of Bristol in 1879 and married Margaret Buchanan in 1881. In the same year he became the Principal of University College, Bristol, and somehow managed to combine that with active research both in organic chemistry and on gases.

Career

William Ramsay formed pyridine in 1876 from acetylene and hydrogen cyanide in an iron-tube furnace in what was the first synthesis of a heteroaromatic compound.[10] In 1887, he succeeded Alexander Williamson as the chair of Chemistry at University College London (UCL). It was here at UCL that his most celebrated discoveries were made. As early as 1885–1890, he published several notable papers on the oxides of nitrogen, developing the skills that he needed for his subsequent work. On the evening of 19 April 1894, Ramsay attended a lecture given by Lord Rayleigh. Rayleigh had noticed a discrepancy between the density of nitrogen made by chemical synthesis and nitrogen isolated from the air by removal of the other known components. After a short conversation, he and Ramsay decided to investigate this. In August Ramsay told Rayleigh he had isolated a new, heavy component of air, which did not appear to have any chemical reactivity. He named this inert gas "argon", from the Greek word meaning "lazy".[2] In the following years, working with Morris Travers, he discovered neon, krypton, and xenon. He also isolated helium, which had only been observed in the spectrum of the sun, and had not previously been found on earth. In 1910 he isolated and characterised radon.[11]

During 1893–1902, Ramsay collaborated with Emily Aston, a British chemist, in experiments on mineral analysis and atomic weight determination. Their work included publications on the molecular surface energies of mixtures of non-associating liquids.[12]

He was appointed a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath (KCB) in the 1902 Coronation Honours list published on 26 June 1902,[13][14] and invested as such by King Edward VII at Buckingham Palace on 24 October 1902.[15]

In 1904, Ramsay received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Ramsay's standing among scientists led him to become an adviser to the Indian Institute of Science. He suggested Bangalore as the location for the institute.

Ramsay endorsed the Industrial and Engineering Trust Ltd., a company that claimed it could extract gold from seawater, in 1905. It bought property on the English coast to begin its secret process. The company never produced any gold.

Ramsay was the president of the British Association in 1911–1912.[16]

Personal life

In 1881, Ramsay was married to Margaret Johnstone Marshall (née Buchanan), daughter of George Stevenson Buchanan. They had a daughter, Catherine Elizabeth (Elska) and a son, William George, who died at 40.

Ramsay lived in Hazlemere, Buckinghamshire, until his death. He died in High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire, on 23 July 1916 from nasal cancer at the age of 63 and was buried in Hazlemere parish church.

Legacy

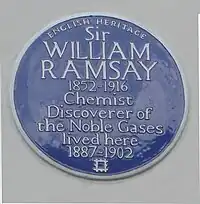

A blue plaque at number 12 Arundel Gardens, Notting Hill, commemorates his life and work.

The Sir William Ramsay School in Hazlemere and Ramsay grease are named after him.

There is a memorial to him by Charles Hartwell in the north aisle of the choir at Westminster Abbey.[17]

In 1923, University College London named its new Chemical Engineering department and seat after Ramsay, which had been funded by the Ramsay Memorial Fund.[18] One of Ramsay's former graduates, H. E. Watson was the third Ramsay professor of chemical engineering.

On 2 October 2019, Google celebrated his 167th birthday with a Google Doodle.[19]

See also

References

- ↑ Thorburn Burns, D. (2011). "Robert Rattray Tatlock (1837–1934), Public Analyst for Glasgow" (PDF). Journal of the Association of Public Analysts. 39: 38–43. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2012. Retrieved 25 November 2011.

- 1 2 Wood, Margaret E. (2010). "A Tale of Two Knights". Chemical Heritage Magazine. 28 (1). Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- 1 2 Glasgow Post Office Directory 1852

- ↑ Waterston, Charles D; Macmillan Shearer, A (July 2006). Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002: Biographical Index (PDF). Vol. II. Edinburgh: The Royal Society of Edinburgh. ISBN 978-0-902198-84-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2006. Retrieved 25 November 2011.

- ↑ Glasgow Post Office Directory 1860

- ↑ Biographical Index of Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002 (PDF). The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. ISBN 0-902-198-84-X. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 January 2014.

- ↑ Ramsay, William (1872). Investigations on the Toluic, and Nitrotoluic Acids. Print. by Fues.

- ↑ "Sir William Ramsay Biographical". The Nobel Prize. The Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ↑ "Ramsay Papers". Jisc Archive Hub. University College London Archives. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ↑ Ramsay, William (1876). "On picoline and its derivatives". Philosophical Magazine. 5th series. 2 (11): 269–281. doi:10.1080/14786447608639105.

- ↑ W. Ramsay and R. W. Gray (1910). "La densité de l'emanation du radium". C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris. 151: 126–128.

- ↑ Creese, M. R. S. (1998). Ladies in the Laboratory? American and British Women in Science, 1800–1900: A survey of their contributions to research. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow. p. 265.

- ↑ "The Coronation Honours". The Times. No. 36804. London. 26 June 1902. p. 5.

- ↑ "No. 27453". The London Gazette. 11 July 1902. p. 4441.

- ↑ "Court Circular". The Times. No. 36908. London. 25 October 1902. p. 8.

- ↑ "Report of the British Association for the Advancement of Science". Archive.org. London : John Murray. 2 October 1912. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ↑ 'The Abbey Scientists' Hall, A.R. p63: London; Roger & Robert Nicholson; 1966

- ↑ " History – UCL Chemical Engineering has a long and distinguished history as a world-leading research department – the first of its kind in the UK. Find out more about some key figures and dates in our history". UCL. 19 July 2018. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ↑ "Sir William Ramsay's 167th Birthday". Google. 2 October 2019.

- Secondary sources

- Morris Travers (1956). The Life of Sir William Ramsay. London: Arnold. ISBN 978-0-7131-2164-3.

- John Meurig Thomas (2004). "Argon and the Non-Inert Pair: Rayleigh and Ramsay". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 43 (47): 6418–6424. doi:10.1002/anie.200461824. PMID 15578783.

- Lord Rayleigh; William Ramsay (1894–1895). "Argon, a New Constituent of the Atmosphere". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 57 (1): 265–287. doi:10.1098/rspl.1894.0149. JSTOR 115394.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Theodore W. Richards (1917). "Sir William Ramsay, K. C. B.". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 56 (1): iii–viii3. JSTOR 983962.

External links

- William Ramsay on Nobelprize.org including the Nobel Lecture 12 December 1904 The Rare Gases of the Atmosphere from Nobelprize.org website

- Sir William Ramsay School

- Ramsay biography at the Wayback Machine (archived 11 January 2006)

- Eponymous school

- Web genealogy article on Ramsay

- Chemical genealogy

- victorianweb biography

- chemeducator biography

- 7/23/1904;This Photograph of Sir William Ramsay Was Taken in His Laboratory Specially for the Scientific American

- Works by or about William Ramsay at Internet Archive

- Works by William Ramsay at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)