Wilmington Square, showing central gardens and surrounding terraces | |

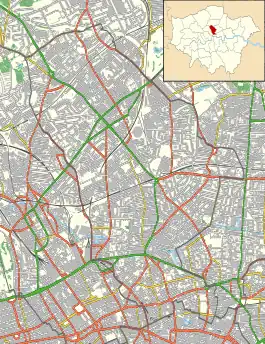

Shown within London Borough of Islington | |

| Postal code | WC1 |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 51°31′36″N 0°06′38″W / 51.526766°N 0.110436°W |

| Construction | |

| Construction start | 1817 |

| Completion | 1841 |

Wilmington Square is a garden square in Clerkenwell, Central London. It is bounded by Regency and Victorian terraces, most of which are listed buildings. The central public gardens contain flower beds and mature trees, a pavilion or shelter, and a water fountain.

History

Spa Fields

The Earls and Marquesses of Northampton were historical owners of land in Clerkenwell including the Spa Fields Estate, which was the location of the mass meeting prior to the Spa Fields riots of 1816. Soon after, the Estate was divided and became one of London’s first post-Waterloo developments.[1] Today, the Estate is the site of Spa Fields park and Spa Green Gardens and the surrounding area, including Exmouth Market and Wilmington Square.[2]

Development

Starting about 1817 the Northampton Estate let plots on a 99-year building lease to a speculator builder named John Wilson to develop the Spa Fields Estate, with the 16 acres (6.5 ha)[1] Wilmington Square at its centre.[2] Wilson (born c. 1780), a Gray's Inn Lane plumber and glazier who had become a builder and developer, had been active in the construction of Doughty Street, Burlington House[3] and Gray’s Inn Road.[1] The square took its name from a subsidiary title of the Marquess of Northampton, Baron Wilmington.[3]

Progress was piecemeal, and the grand south terrace (nos. 1-12) and south-east corner (nos. 13-14) were only completed in 1824.[1] The square was originally planned to be as large as nearby Myddelton Square, but in 1825 Wilson wrote that “the neighbourhood was not adapted to the occupation of houses of so good a description as those he had begun to build in it”.[3] As a result of this and a depressed market[2] the size of the square was reduced from the original plan by lessening its depth, and the rate of the buildings was also reduced. The antiquary Thomas Cromwell noted in 1828 that, presumably for financial reasons, the square was “completed in a form more circumscribed than was at first determined on, and with houses of a less lofty character”.[4] The two ends of the north side were completed in 1829-31, but the centre (nos. 38-39) was not completed until 1841, by when Margery Street had been built behind the terrace, so that the road planned for the north side of the square had to be replaced with a high pedestrian walkway.[1][3] The east side was completed by 1825, and the west side by 1829. The square’s curtailment led to its becoming a backwater, on the edge of squalid courts which later became slums.[1]

By 1906, the area’s “uninteresting” early-19th century architecture was considered to be part of the “hideously inartistic style of that period”.[5] Today, the simple and elegant uniformity of terraces and squares like Wilmington Square are much admired and reflected in the premiums paid when purchasing a Georgian property.[6]

Later changes

No. 1A’s side entrance is a post-Second World War addition.[7]

Nos. 8-11 were severely damaged during the war[8][9] and reconstructed laterally in 1951 as eight flats.[10]

Nos. 18-21 were the subject of an early lateral conversion by the Northampton Estate in 1920.[3]

Nos. 22-24 were rebuilt as Police Flats during the 1930s in the Expressionist style,[1] and now form part of Wilmington Street.

Nos. 38 and 39 were wholly rebuilt by Islington Council in 1968-69.[11][10]

Description

The square was built during more than two decades, and has ‘unbalanced’ terraces of varying design.[1][12] All the houses have stuccoed ground floors with circular-headed windows and area railings. Many have balconies or window guards. All are four floors plus basement except the north side (nos. 25-37), which is built on higher ground. This side is a floor less in height, with a raised basement and a pedestrian walkway adjoining the centre gardens. The east (nos. 13-21) and west (nos. 38-47) sides are similar to each other. On the more elaborate south side (nos. 1-12), the centre and end buildings have pediments and circular-headed first-floor windows. The façade of the rebuilt nos. 8-11 is an approximate facsimile of the original houses, with a single front entrance.

Wilmington Square Gardens

The square's D-shaped central garden enclosure of almost 1 acre (0.40 ha) was at first reserved for the private use of the square's lessees. In 1883 the possibility was considered of building a church (which was later realised as Our Most Holy Redeemer, Exmouth Market) in the square.[3] Instead, in the wake of the investigations of the Royal Commission on the Housing of the Working Classes, in 1885 the gardens were made over by Lord Compton to the Finsbury vestry for public use, and the Metropolitan Public Gardens Association offered to run the gardens for the benefit of the poor.[2]

Flowers were planted and seating installed, together with the late 19th century pavilion or shelter that can still be seen today. In the gardens is a drinking fountain with the remains of a dedication inscription for the public garden. There are some notable trees including numerous small ornamental trees and conifers.[13]

The cast-iron railings date to 1819, with reeded square-section standards and pine-cone or pineapple finials. There is a blocked gate at the centre of the south side.[3] The railings appear to have survived removal in the Second World War when many garden squares lost their railings. This was supposedly to provide scrap metal for munitions, but there is some scepticism as to whether they were actually used for this purpose.[14]

Residents

The first residents of Wilmington Square included engravers, solicitors, and figures from the world of arts, and also merchants and trades people.

George Almar (1802-1854)], a prolific local playwright, lived at no. 43 in the early 1830s.[15] Amongst many other works, he authored Don Quixote or The Knight of the Woeful Countenance: A Romantic (Musical) Drama in Two Acts in 1833, Peerless Pool and The Knights of St John – a new Grand military and Chivalric Spectacle,[15] and the first stage adaptation of David Copperfield, entitled Born with a Caul in 1850.[16]

Rev. William John Hall M.A. (1793-1861), lived at no. 10 in 1835. He compiled the Church of England collection of hymns and psalms known as The Mitre Hymn-Book, which was first published in 1836 and attained a circulation of 4 million copies.[1]

Golding Bird, Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians and authority on kidney diseases, lived at his family home at no. 22 until his marriage in 1842.[3]

Herbert Spencer, philosopher and political theorist, was employed at no. 27, then the offices of a railroad engineer and promoter, William B. Prichard in 1845-6.[10]

By the 1850s the square had become a centre for the making of artificial flowers by French and German immigrants.[3]

Joseph Stirling Coyne, Irish dramatist and journalist, lived at no. 2 in the 1850s.[3]

E. L. Blanchard, dramatist and playwright, gave Wilmington Square as his address in the 1850s.[3]

Edward Daniel Johnson, watch and marine chronometer maker, lived and worked at no. 9 from 1855,[17] where he produced the majority of his work.

Frederick Goulding, printer of etchings and lithographs, studied at a school of art in the square in 1858 and 1859.[18]

By the 1860s, many of the houses were sub-divided for both residential and commercial use. In the 1880s more than half of the square's houses were in divided occupation, but with a continuing professional presence, including clergymen, doctors and architects.

Aubrey Beardsley, illustrator, worked in the office of Ernest Carritt, the District Surveyor, at no.20 as an adolescent in 1888 for a salary of sixteen pounds a year.[3]

Charles Booth’s poverty map of c.1890 shows Wilmington Square households as “Middle class. Well-to-do.”[19]

Frederick Hammersley Ball (1879-1939), artist, lived at no. 20 in 1902.[10]

In the late twentieth-century, gentrification resulted in the re-conversion of flats to houses, especially on the north side, and well-known figures such as the politician Peter Mandelson[20] and the ceramic and tapestry artist Grayson Perry[21] became residents.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Cosh, Mary (1990). The Squares of Islington Part I: Finsbury and Clerkenwell. London: Islington Archaeology & History Society. pp. 93–98. ISBN 0 9507532 5 4.

- 1 2 3 4 Temple, Philip, ed. (2008). "Introduction". Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. London: London County Council. pp. 1–21. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Temple, Philip, ed. (2008). "Wilmington Square area". Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. London: London County Council. pp. 239–263. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

- ↑ Cromwell, Thomas (1828). History and Description of the Parish of Clerkenwell. London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green, Sherwood and Co., and J. and H. S. Storer. p. 316. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ↑ Mitton, Geraldine Edith (1906). Clerkenwell & St. Luke's; comprising the Borough of Finsbury. London: Adam & Charles Black. p. 73. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ↑ Kelly, John (6 September 2013). "Which era of house do people like best?". BBC News.

- ↑ "Houses in Wilmington Square". London Picture Archive. City of London Corporation. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- ↑ "Official list entry". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- ↑ "Houses in Wilmington Square". London Picture Archive. City of London Corporation. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 Willats, Eric A. (1987). Streets with a Story: Islington (PDF). ISBN 0 9511871 04.

- ↑ "Buildings in Wilmington Square". London Picture Archive. City of London Corporation. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- ↑ "Wilmington Square". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ↑ "Inventory Site Record". London Gardens Trust. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ↑ Peter Watts (17 April 2012), "Secret London: the mystery of London's World War II railings", The Great Wen

- 1 2 Cosh, Mary (2005). A History of Islington. London: Historical Publications Ltd. p. 156. ISBN 0 948667 97 4.

- ↑ Davis, Paul B (1999). Charles Dickens from A to Z. New York: Checkmark Books. pp. 92–93. ISBN 978-0-8160-4087-2.

- ↑ 1861 England census for 9 Wilmington Square

- ↑ Hardie, Martin (1912). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography (2nd supplement). Vol. 2. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 143–144.

- ↑ Booth, Charles. "Inquiry into Life and Labour in London: Maps Descriptive of London Poverty". Charles Booth's London. London School of Economics. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- ↑ Razaq, Rashid. "Rocketing price of Mandelson's old flat". Evening Standard. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ↑ La Placa, Joe. "London Calling". Artnet. Artnet Worldwide Corporation. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

External links

Historic England listed building entries for Wilmington Square:

- Numbers 1 to 12, 12A to 12C (consecutive) and attached railings, 1-12, 12A-12C, Wilmington Square

- Numbers 13 to 19, 19A, 20 to 20B, 21 and attached railings, 13-19, 19A, 20-20B, 21, Wilmington Square

- Numbers 25 to 37 (consecutive) and attached railings, 25-37, Wilmington Square

- Numbers 38 to 39 (consecutive) and attached railings, 38-39, Wilmington Square

- 40 to 47, Wilmington Square, London, WC1X 0ET

- Railings round central garden, Wilmington Square