| Winchester Bible | |

|---|---|

| |

| Patron | Bishop of Winchester Henry of Blois |

| Language | Latin |

| Date | 1160 |

| Genre | Illuminated manuscripts |

The Winchester Bible is a Romanesque illuminated manuscript produced in Winchester between 1150 and 1175 for Winchester Cathedral. With folios measuring 583 x 396 mm., it is the largest surviving 12th-century English Bible.[1] The Bible belongs to a group of large-sized Bibles that were made for religious houses all over England and the continent during the 12th century.[2] The Winchester Bible is important to understanding the history of medieval art, because it was left only partially completed, giving insight into the creation and production of these kinds of Bibles. It can still be seen in the Winchester Cathedral Library, which has been its home for more than eight hundred years. Before it was returned to Winchester Cathedral, the Bible had many owners and suffered because of it. Pages have been removed and torn out; one of those pages is known as the Morgan Leaf and is now owned by the Morgan Library in New York.

History

Origin

During the Romanesque period, the focus of major illumination in Western Europe moved from the Gospel Book to the Psalter and the Bible. The Winchester manuscript is one of the most lavish Bibles of this kind. The manuscript was probably commissioned by the Bishop of Winchester, Henry of Blois, for the Cathedral. The book would have been originally housed in Winchester Cathedral's collection of sacred texts.[3] One theory is that this was the actual Bible that was given to Witham Charterhouse in Somerset. This suggestion, however, is not widely accepted. If it was in fact the same manuscript that was given to Witham, that would imply that all the text and illuminations would have had to have been completed by 1186. It is more widely thought that the Bible could have been worked on all the way up to 1190.[4]

Provenance

Over the years, the manuscript has suffered at the hands of thieves and collectors, the full extent of which is unknown. Currently, the Bible is at Winchester Cathedral Library. One leaf of the Bible, however, has been removed and is now housed at the Morgan Library.

Description

The Bible contains 936 pages, as 468 leaves of calf-skin parchment, which equates to hides of about 250 calves.[5] It is thought that the Winchester Bible was worked on between 1160 and 1190, either as one continuous project from c. 1160-1180, or in two campaigns, the first starting around 1160 and the other starting 1170-1190.[4] Its first recorded mention, in 1622, describes the manuscript as a Bible in two volumes.[1] Over the years it has been rebound twice, first in 1820, when it was divided into three volumes, and again in 1948.[6] The Bible now spans four separate volumes, bound in gold-tooled cream-coloured leather.[6]

Decoration

The artwork of the Winchester Bible is incomplete. Many illuminations were left unfinished, while others were deliberately removed later on. The illuminations throughout the manuscript appear in varying stages of completion, ranging from rough outlines and inked drawings to unpainted gilded images and figures complete in all but the final details. In all, 48 of the major historiated initials that begin each book stand complete.[7] The different books of the Bible are determined by large decorative first initials; three books were important enough to have full-paged scenes dedicated to them. I Samuel, Judith, and Maccabees all have full page frontispieces but only I Samuel's was actually completed; the other two were left only as drawings.[4]

The decoration of the manuscript involved many different artists with different styles, both figural and decorative. The presence of various styles makes it hard to determine the exact date of the Bible. The different styles could point towards two different periods the Bible was worked on, one earlier and one later. However, it could also imply that both traditional and ground-breaking artists of the time worked on the piece during the same period.[4]

Text

Although many of the illuminations remain unfinished, the Latin text itself is complete. The Bible consists of the entire Vulgate, comprising both Old and New Testaments, two versions of the Psalms, and the Apocrypha, and is written in the Latin of St Jerome. Interestingly, the books of the Bible are all started on the same page as the last page of the previous book. The text also includes many abbreviations and shortened versions of words. This unusual system was thought to have been used to save space and money because the materials were so expensive.[3]

Creation

Preparation

To prepare each calf skin to be included in the Bible the skin had to be soaked in a lye/water solution. The hair and skin then had to scraped off, and the skin had to stretched, dried and processed. Because so many materials were needed to make manuscripts like the Winchester Bible, supplies typically needed to be procured from outside of England. For example, Master Hugo, the maker of the Bible for the Abbey of Bury St Edmunds, had to obtain supplies from Ireland.[5]

Transcribing

Due to the large size of the Bible, it had to be organized into many quires of four bi-folios. Each bi-folio would have been pricked for ruling to ensure the pages and lines of text were arranged properly. Ruling lines were lightly scored into the parchment, which the scribe would use as guides like the lines of a notebook. Unlike other manuscripts of this size, the Winchester Bible was written by the hand of one scribe with a goose feather quill. It is thought that the scribe would have been an accomplished member of the Winchester's Priory of St Swithun, and the work has been estimated to have taken four years to complete.[5] After the text was written it was reviewed by a monk, and then colour was added to important words and letters.[3]

Art

The illuminations reflect the work of at least six different hands, and was worked on for 25 years between 1150 and 1175.[5] The art historian Walter Oakeshott first identified and named these artists in 1945,[8] referring to them as the Master of the Leaping Figures, the Master of the Apocrypha Drawings, the Master of the Genesis Initial, the Master of the Amalekite, the Master of the Morgan Leaf, and the Master of the Gothic Majesty. The Apocrypha Drawings Master was likely trained in France or Normandy since his style of energetic and mannered poses more closely resembles French art at the time, more so than English.[4] The Master of Leaping Figures is almost positively English. The dramatic poses and leaping movements are hallmarks of the Byzantine style that was influential in Winchester, starting around 1130.[4] The Master of the Morgan Leaf, the Amalekite Master, the Master of the Genesis Initial, and the Master of the Gothic Majesty all have varying styles derived from Byzantine influences and are precursors to the Early English Gothic Style.[4]

Close examination of the illustrations revealed that multiple artists would have worked together on the same piece within the manuscript. First a dry point drawing would be traced by one artist, then another would apply gilding or silver accents, and then another artist would add coloured paint.[5] Pigments were sourced from plants, animals, and minerals. The most expensive pigment to produce was not the silver or gold gilding, but the bright blue ultramarine which could only be sourced from lapis lazuli from Afghanistan.[5] Forty-eight illuminated letters were completed, and many more were left unfinished.

Contents

Unfortunately, the Bible no longer holds all of its original pages. Nine illuminated initials and at least one full-page illustration have been removed entirely. Of these, only one (the initial of the Book of Obadiah) has been recovered and restored to the text.[7] Another missing leaf was recovered but never restored to the book. This individual leaf is now housed at the Morgan Library in New York, and is commonly referred to as the Morgan Leaf. Whether other similar full-page miniatures have been removed is unknown.

The Morgan Leaf

This page of the Winchester Bible is unique as it is one of three full-paged illuminations in the manuscript, and it is the only one that has been completed. This leaf shows scenes from the lives of Samuel on the recto and of King David on the verso.[3] The Morgan Leaf was painted by the Master of the Morgan Leaf, and is why he was named as such. The Morgan Leaf is characterized by the bold emotion shown in the figures, with less attention paid to the details. The bold blues and reds also add to the emotional depth of the scene.

The leaf was removed during the rebinding process in 1820, and was sold to John Pierpont Morgan in 1912 for 30,000 francs. The first person to recognise the connection between the Morgan Leaf and the Winchester Bible was the British Museum's Keeper of Manuscripts, Eric Millar, in 1926. The identification was later supported by other art historians, and supported by the evidence that the original drawing of the Morgan Leaf was also done by the same hand that did the underdrawings of the Winchester Bible, the Master of the Apocrypha Drawings.[6] This was proven by comparison of the underdrawings of the Morgan Leaf to the incomplete illuminations of the Winchester Bible.

Gallery

Fol.169. Lamentations 5. The prayer of Jeremiah

Fol.169. Lamentations 5. The prayer of Jeremiah- Fol.5, detail. Christ at the Last Judgment

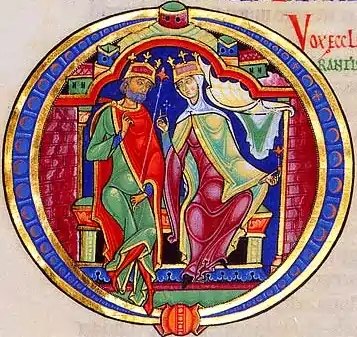

- Fol.120v. Beginning of Second Kings with historiated initial showing the messengers of Elijah and Ahaziah

The Morgan Leaf. Scenes from the life of King David

The Morgan Leaf. Scenes from the life of King David Illuminated page of the Winchester Bible.

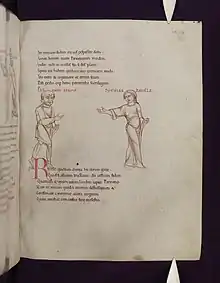

Illuminated page of the Winchester Bible. Comedies of Terence. Incomplete page of the Winchester Bible.

Comedies of Terence. Incomplete page of the Winchester Bible.

Notes

- 1 2 Donovan, Claire (1993). The Winchester Bible. Toronto and Buffalo: University of Toronto Press. p. 3. ISBN 0-8020-6991-6.

- ↑ Wellesley, Mary (2021-10-07). Hidden Hands: The Lives of Manuscripts and Their Makers. Under the heading Winchester Bible. Quercus. ISBN 978-1-5294-0095-3.

- 1 2 3 4 "The Winchester Bible". Winchester Cathedral. Retrieved 2020-04-08.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Grove Encyclopedia of Medieval Art Architecture". Oxford Reference. Retrieved 2020-04-22.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Little, Charles (January 21, 2015). "The Making of the Winchester Bible". The Met 150.

- 1 2 3 Voelkle. "The Morgan Leaf and the Winchester Bible". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2020-04-22.

- 1 2 Donovan 1993, 6.

- ↑ Oakeshott, Walter (1945). The Artists of the Winchester Bible. London: Faber and Faber.

Further reading

Books:

Oakeshott, Walter (1972). Sigena: Romanesque Painting in Spain & the Winchester Bible Artists. London: Harvey, Miller and Medcalf. ISBN 0-8212-0497-1.

Oakeshott, Walter (1981). The Two Winchester Bibles. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-818235-X.

Websites:

Little, Charles T. “The Making of the Winchester Bible.” The Met 150. The Metropolitan Museum of art. January 21, 2015. https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2014/winchester-bible/blog/posts/making-of-the-winchester-bible

"The Winchester Bible." Winchester Cathedral.org. The Winchester Bible. https://www.winchester-cathedral.org.uk/our-heritage/cathedral-treasures/the-winchester-bible-details/

"The Grove Encyclopedia of Medieval Art and Architecture". Oxford Reference. The Oxford University Press. 2013.https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195395365.001.0001/acref-9780195395365

Voelkle, William M. "The Morgan Leaf and the Winchester Bible." The Met 150. The Metropolitan Museum of art. February 10, 2015. https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2014/winchester-bible/blog/posts/the-morgan-leaf-and-the-winchester-bible

Films

Films for the Humanities & Sciences (Firm), and Films Media Group. 2011. Ancient Bibles. New York, N.Y.: Films Media Group. http://digital.films.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?aid=13753&xtid=55768.