The Winchester and Potomac Railroad (W&P) was a railroad in the southern United States, which ran from Winchester, Virginia, to Harpers Ferry, West Virginia (Virginia until 1863), on the Potomac River, at a junction with the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O).[1] It played a key role in early train raids of the B&O during the beginning months of the American Civil War.[2]

The W&P Railroad was acquired by the B&O in 1902, and subsequently became part of CSX Transportation.

Founding and early history

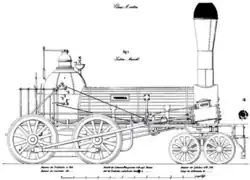

Most railroads built in Virginia before the Civil War connected farming and industrial centers to ports such as Alexandria and Norfolk. Towns west of the Blue Ridge Mountains needed rail transportation to connect with port cities but were hampered by the ability to cross the rugged Blue Ridge. When the newly formed B&O Railroad (estab. 1827) was planned to cut across the northern end of the lower Shenandoah Valley, the Virginia General Assembly chartered the W&P Railroad in 1831. Routes were then surveyed by the Army Corps of Topographical Engineers from 1831 to 1832. Construction of the W&P began in 1833 with Moncure Robinson as head engineer. It was completed by 1836, beginning its first operations on March 14 of that year,[3]: 191 when the locomotive "Tennessee", "the first ever seen in the valley of Virginia", made its first trip from Harpers Ferry to Winchester "in style".[4]

The B&O reached Harpers Ferry in 1834 (via ferry from Sandy Hook, Maryland).[3]: 195–6 A final rail connection with the B&O was completed in January 1837 when the Winchester and Potomac was connected by the first B&O Railroad Bridge completed across the Potomac River, tying the lines together in a junction on the Virginia side of the river.[5] This was also the first ever intersection of two railroads in the United States.

The W&P was a standard gauge road with rails of 16.5 pounds per yard (8.2 kg/m) flat bar constructed upon ties cut from white oak and locust. The main line ran 32 miles (51 km) with another 2.5 miles (4 km) of sidings and turnouts. The railroad terminated at the corner of Water and Market Streets in Winchester. The Winchester depot immediately became a key economic hub serving merchant traders in Winchester for commodities such as wheat, hide, fur, tobacco and hemp. The north end of the rail line also served the thriving industrial town of Virginius Island, which sat astride the Shenandoah Canal on the south side of Harpers Ferry.

| Station | Distance | |

|---|---|---|

| mi | km | |

| Harpers Ferry, West Virginia | 0 mi | 0 km |

| Halltown, West Virginia | 6 mi | 9.7 km |

| Charlestown, West Virginia | 10.5 mi | 16.9 km |

| Cameron's/Aldridge, West Virginia | 14 mi | 23 km |

| Summit Point, West Virginia | 18 mi | 29 km |

| Wadesville, Virginia | 21 mi | 34 km |

| Stephenson, Virginia | 26 mi | 42 km |

| Winchester, Virginia | 31.5 mi | 50.7 km |

This connection to the B&O caused much concern politically, since this potentially enabled all farming and industrial produce in the Great Appalachian Valley region of Virginia to ship out of ports in Baltimore, Maryland and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania rather than through Virginian ports. Therefore, this railroad was not authorized for connections further south. Those southern portions of the Shenandoah Valley were served later by other railways such as the Manassas Gap Railroad, which connected Mount Jackson, Virginia to the Manassas Junction on the Orange and Alexandria Railroad, and the Virginia Central Railroad, which connected Staunton to Richmond.

John Brown's raid

The W&P was threatened during the events following John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, and was a possible avenue for either an invasion into Virginia, or for a rescue operation of John Brown and other prisoners. The Governor of Virginia sent this notice to John W. Garrett, President of the Baltimore & Ohio, concerning Virginia Militia shutdown and control of both the W&P and B&O in connection with the raid in 1859.

Executive Department,

Richmond, 28th Nov., 1859.

J. W. Garrett, Esq.,

President, &c.

From information in possession of the Governor, of a contemplated attempt to rescue the prisoners condemned to death at Charlestown, he has deemed it proper to issue a proclamation taking possession of the Winchester & Potomac Railroad, on the first, second and third days of December next, and it will be held under impressment, with a guard, for the use and occupation of Virginia troops alone, and no transportation will be permitted other than for them. Under these circumstances, he requests me to suggest to you, as President of the Balt. & Ohio Railroad Company, the propriety of stopping all trains on your road on the first and second of December, other than for carrying the United States mail. Passengers coming through Virginia on those days will not be permitted to pass. Major General Taliaferro, in command at Charlestown, has orders to this effect.

GEO. W. MUMFORD,

Secretary of the Commonwealth

Civil War

By the start of the Civil War in 1861, W&P owned six locomotives: Ancient, Pocahontas, Farmer, President, Virginia and Potomac, all of which had a 4-4-0 wheel arrangement, except for Farmer, which was 4-2-0. Rolling stock included four passenger cars, one mail/baggage car, forty freight cars and eight repair cars. Officers of the company included William L. Clark, President and Chief Engineer Thomas Robinson Sharp. On June 18, 1861, the W&P Chief Engineer Sharp was commissioned a Captain in the Confederate States Army and was instrumental in various railroad operations, constructions and raids for the Confederacy and the Army of Northern Virginia, especially under Stonewall Jackson.

1861

The W&P was of potential value to the Confederates for any need to attack Harpers Ferry[6] and did serve a useful role in the movement of Virginia Militia troops to defensive positions in and about Harpers Ferry.[7] Although it could potentially be used to feed Confederate forces into the defenses of western Virginia via the B&O, by running along the northern border of the Confederate states, it would have been vulnerable to attack, possibly stranding large units to the west. So, due to its very northern location, and mere spur-like connection to the B&O, its overall potential usefulness to the Confederacy was not great.[6] The greatest use and value in the W&P came in the first eight months of the war, from May 1861 to January 1862, when it was utilized to ship light machinery from the Harpers Ferry arsenal down to Winchester, and from there overland to Strasburg and the Manassas Gap Railroad. The light strap rails did not permit heavy shipments, and this was a constant factor until late in the war.[8]

The W&P was a key asset used during the Great Train Raid of 1861, when Stonewall Jackson raided the B&O, removing, capturing, or burning a total of 67 locomotives[9] and 386 railway cars, and taking 19[10] of those locomotives and at least 80 railroad cars onto Confederate railroads. After initially trapping this rolling stock on the Virginia-controlled portion of the B&O, Jackson immediately "helped himself to four small locomotives not too heavy for the flimsy flat-bar rails of the Winchester & Potomac, and had them sent to Winchester,"[2] where they were disassembled near Fort Collier, mounted onto special dollies and wagons, and hauled by 40-horse teams "down the Valley turnpike to the [Manassas Gap] railroad at Strasburg,"[9] reassembled and placed back on the tracks "which connected with the Virginia Central and the entire railroad system of the Confederacy."[11] Through this event, the Chief Engineer of the W&P, Thomas R. Sharp, became heavily involved with what was later referred to as the "railroad corps" of the Confederacy, disassembling and moving other locomotives, cars, rails, ties, and machinery from the B&O to Winchester for storage and subsequent removal deeper into Confederate territory. His success in the raid at the end of May 1861 by taking the four small locomotives over his railroad to Winchester earned him a commission as a Captain in the quartermaster service on June 18, 1861, and the new task of removing as many as possible of the remaining locomotives and rail cars still stranded up in Martinsburg.[10]

Throughout the summer and fall of 1861, Capt. Thomas Sharp was busy supervising the removal of trains, equipment, rails and ties from the B&O, the "South's one unfailing source of supply."[12] After the big summer campaigns of 1861 were mostly finished, Stonewall Jackson returned to Winchester and continued in his devotion of energy to "uprooting track west of Martinsburg" and were "able to deliver 3,000 tons of Baltimore & Ohio rails to the Winchester & Potomac Railroad in December, 1861."[13]

1862

In the opening months and winter of 1862 most of the Baltimore & Ohio rolling stock and rail ties that had been captured and stored in Winchester, with the help of W&P railroaders, were evacuated and used in various other Confederate railroads, such as the Centreville Military Railroad. The W&P at that point, however, had very little transportation value for either Confederate or Union forces for the rest of the war, and was not used by the Confederacy anymore after the spring of 1862,[14] when it was seized by Union forces under Major General Nathaniel P. Banks.[15]

Both the western portion of the Manassas Gap Railroad and the W&P Railroad were effectively under the control of Banks in the spring, and were going to be used as part of a plan developed by Major General George B. McClellan to support Union operations in that area. McClellan's plan was to connect the Manassas Gap Railroad and the W&P with a line between Winchester and Strasburg, creating a "complete circle of rails" from the Union capital at Washington, D.C. to the Shenandoah Valley by either the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad or the Orange and Alexandria Railroad.[16]

Sometime in 1862, likely when McClellan occupied and controlled the W&P, its locomotives Ancient and President were captured, and later sold after the war. The Ancient was sold to J. Neilson in 1865, and the President was sold to the West Jersey and Atlantic Railroad.

Late in May, as Stonewall Jackson was busy routing the Fifth Corps under Banks, the B&O was shipping troops forward to Banks. "A troop train, in fact, arrived at Winchester (on the W&P) just as Banks began his retreat. Three companies got off and the remainder of the regiment rode back to Harpers Ferry."[17] As Banks retreated from Winchester, the Confederates occupied the northern Shenandoah Valley, burned the W&P's principal bridges, and tore up all the track. After Jackson evacuated the area in early June, the Union Army began repairing the W&P, but heavy rains washed the bridges out, and the W&P was not restored to service until June 20, 1862.[18]

On June 22, 1862 a train carrying soldiers from New York and the 3rd Delaware Volunteer Infantry over turned between Wadesville and Summit Point, WV. One New Yorker, John P. Kopk was killed and fifty two were injured. Most of the injured were from the 3rd Delaware. https://www.nytimes.com/1862/06/23/news/winchester-serious-railroad-accident-train-off-track-number-soldiers-killed.html

In August 1862, as Major General John Pope was busy retreating and being defeated by General Lee in the Northern Virginia Campaign, Confederate intelligence learned that the W&P and the Baltimore & Ohio were being used to bring reinforcements to Pope. Reverend J. W. Jones of Charles Town, West Virginia, reported that the Northern government was using the railroad for that purpose, and this was confirmed three days later when Major General J.E.B. Stuart captured papers and letters belonging to Pope in a raid on his headquarters.[19]

Also in August, Confederate lieutenants George Baylor and Milton Rousss of Company B, 12th Virginia Cavalry, led a small raid attacking the W&P between Summit Point and Cameron's Depot, capturing eight Union soldiers, $4,000 in cash and food supplies.

Following the Battle of Antietam in the 1862 Maryland Campaign, the Confederate States Army once again controlled the northern Shenandoah Valley for a brief time. The Confederates wanted to remove all the new rails laid down on the W&P, but due to a lack of wagons, were unable to take it.[20] Therefore, General Robert E. Lee ordered Major General Lafayette McLaws' division to once again destroy the W&P in order to foil any attempt by McClellan to follow the Army of Northern Virginia. McClellan, meanwhile, on October 10, was making arrangements with the Baltimore & Ohio to reconstruct the W&P with heavier duty T-rails, locomotives and trains for planned future Union Army operations. The Baltimore & Ohio evaluated McClellan's plan, and replied that they did not have either the ties or rails to do the job, and that it would take at least six weeks to do the job, recommending that the Manassas Gap Railroad be repaired instead.[21] McClellan then abandoned his plan to upgrade the W&P on October 12, and after a reconnaissance by Brigadier General A. A. Humphreys on October 19, the Union Army discovered that the W&P had been destroyed by the Confederates, making the upgrade plan even more unfeasible.[20] In late October, General Robert E. Lee reported removal of the iron from the railroad for use elsewhere in the Confederacy.

1863

During the first half of 1863, Winchester, Virginia, the terminus of the W&P, was occupied by Major General Robert H. Milroy, who made no use of the railroad. Resistance to occupation in the Valley began to grow, and the 43rd Virginia Cavalry Battalion was raised in the area under Major John S. Mosby, also known as the "Gray Ghost". On June 15, after a sweeping rout of Milroy in the Second Battle of Winchester, the Confederates once again controlled the northern Shenandoah Valley as they marched to the Potomac River during the Gettysburg Campaign. Two days later, "Captain T. B. Lee of the Corps of Engineers, C.S.A., was ordered to proceed to the lines of the Winchester & Potomac and the Baltimore & Ohio to collect any machinery, tools, rolling stock, or portions thereof which fell into Confederate hands. He was instructed to arrange with Lee's chief quartermaster, Colonel J. L. Corley, for men and wagons to transport the material down the Valley turnpike."[22] By the end of 1863 the W&P had been practically and nearly completely destroyed by the actions of armies on both sides, and the Confederates, who remained in loose control of the Valley, had no desire to repair or use the railroad, but rather desired to keep it out of service.

1864

In March and April 1864 Union forces, observed by Colonel John S. Mosby, were surveying the W&P and began repairing the road and laying rails, in preparation for advancements into the Valley. This report was relayed by Major General J.E.B. Stuart to General Robert E. Lee, saying, "It is stated that preparations are making to rebuild the [W&P] railroad from Harper's Ferry to Winchester, which would indicate a reoccupation of the latter place. The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad is very closely guarded along its whole extant. No ingress or egress from their lines is permitted to citizens as heretofore, and everything shows secrecy & preparation." The W&P Railroad was not actually re-opened by the Union for service until later in 1864.

After Major General Philip Sheridan pursued Lieutenant General Jubal A. Early south in the Shenandoah Valley, clearing the north end of Confederate forces, the Union Army set about, once again, and for the last time, repairing the W&P, reconstructing 26 miles (42 km) of roadway to serve Sheridan.[23]

1865

The W&P remained in Union Army control through the first half of 1865, and was the next to last of the Virginia railroads to be turned over to the Virginia Board of Public Works, sometime after June 30.[23]

Post bellum

Following the war, in 1866, control of the railroad was returned to the company and stock holders, who decided to lease the right–of-way to the B&O Railroad. In 1870 the new Winchester and Strasburg Railroad was built, which connected Harpers Ferry to the Manassas Gap Railroad at Strasburg, enabling a connection southwest up the Shenandoah Valley to Harrisonburg. Eventually the Baltimore & Ohio "purchased the Winchester & Potomac" and "constructed a line the length of the Valley" to Lexington, where it joined a spur of the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad.[24] Throughout the Reconstruction era, northern railroad companies were able to charter new lines and construct railroads that connected the entire Shenandoah Valley north into Pennsylvania, and south into Tennessee and North Carolina.

In 1896 the United States Supreme Court ruled in a lawsuit, overturning a previous judgment in favor of W&P Railroad Company for $30,340, for the value of the iron rails that were removed in 1862 during the Civil War. The W&P claimed that its stock owners were loyal citizens during the war, and that the United States had taken possession and control of the valley up to Winchester, and then had removed its strap and T-rails over to the Manassas Gap Railroad for service, as well as storage in Alexandria, and they were never returned. Furthermore, W&P had paid Manassas Gap $25,000 (~$586,481 in 2022) in 1874 for rails that had been put on to the W&P.

20th century

In 1902 the W&P Railroad was acquired by B&O Railroad, marking 71 years of total existence for the W&P. The line finally came under control of CSX Transportation as its Shenandoah Subdivision.

Notes

- ↑ Black, p. xxiii

- 1 2 Johnston, p.23

- 1 2 Dilts, James D. (1996). The Great Road: The Building of the Baltimore and Ohio, the Nation's First Railroad, 1828–1853. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2629-0.

- ↑ "(Untitled)". National Gazette (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania). March 15, 1836. p. 2 – via newspapers.com.

- ↑ Reynolds, p.18

- 1 2 Johnston, p.5

- ↑ Tucker, p.33

- ↑ Johnston, p. 257

- 1 2 Johnston, p.24

- 1 2 Shriver

- ↑ Hungerford, Vol II, p.7

- ↑ Johnston, p.36

- ↑ Johnston, p.36 citing Official Records, II, pp.981,987

- ↑ Johnston, p.43

- ↑ Black, p.86

- ↑ Johnston, p. 50; "McClellan's idea was expressed in a letter to Secretary of War Stanton on March 28, 1862."

- ↑ Johnston, p.270

- ↑ Johnston, p.54

- ↑ Johnston, pp.277-278

- 1 2 Johnston, p. 282

- ↑ Johnston, pp. 104-105

- ↑ Johnston, p.291

- 1 2 Johnston, p.253

- ↑ Johnston, p.269

References

- Black, Robert C. The Railroads of the Confederacy. The University of North Carolina Press, originally 1952.

- Johnston II, Angus James, Virginia Railroads in the Civil War, University of North Carolina Press for the Virginia Historical Society, 1961.

- Reynolds, Kirk; Oroszi, Dave (2000). Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. Osceola, WI: MBI. ISBN 0760307466. OCLC 42764520.

- Shriver, Ernest, Stealing Railroad Engines, from Tales from McClure's War: Being True Stories of Camp and Battlefield, New York, Doubleday & McClure Co., 1898.

- Tucker, Spencer C., Brigadier General John D. Imboden: Confederate Commander in the Shenandoah, University Press of Kentucky, 2002, ISBN 0-8131-2266-X