Wojciech Kilar | |

|---|---|

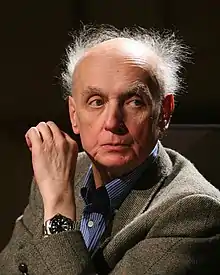

Kilar in 2006 | |

| Born | 17 July 1932 Lwów, Poland |

| Died | 29 December 2013 (aged 81) Katowice, Poland |

| Nationality | Polish |

| Occupation | Composer |

| Spouse |

Barbara Pomianowska

(m. 1966; died 2007) |

Wojciech Kilar (Polish: [ˈvɔjt͡ɕɛx ˈkʲilar]; 17 July 1932 – 29 December 2013) was a Polish classical and film music composer. One of his greatest successes came with his score to Francis Ford Coppola's Bram Stoker's Dracula in 1992, which received the ASCAP Award and the nomination for the Saturn Award for Best Music.[1] In 2003, he won the César Award for Best Film Music written for The Pianist,[2] for which he also received a BAFTA nomination.[3]

Biography

Kilar was born on 17 July 1932 in Lwów (then Poland; since 1945 Lviv in UkrSSR, now Ukraine).[4] His father was a gynecologist and his mother was a theater actress. Kilar spent most of his life from 1948 in the city of Katowice in Southern Poland,[4] married (from April 1966 to November 2007) to Barbara Pomianowska, a pianist.[5] Kilar was 22 years old when he met 18-year-old Barbara, his future wife.[6]

Education

After studying piano under Maria Bilińska-Riegerowa and harmony under Artur Malawski, he moved from Kraków to Katowice in 1948, where he finished his music middle school in the class of Władysława Markiewiczówna, after which he went to the State College of Music (now the Music Academy) in Katowice where he studied piano and composition under Bolesław Woytowicz, graduating with top honours and the award of a diploma in 1955[4][7] He continued his post-graduate studies at the State College of Music (now the Music Academy) in Kraków from 1955 to 1958.[4] In 1957 he took part in the International New Music Summer Course in Darmstadt.[4] In 1959–60 a French government scholarship enabled him to study composition under Nadia Boulanger in Paris.[4]

Music career

Kilar belonged (together with Bolesław Szabelski, his student Henryk Górecki and Krzysztof Penderecki) to the Polish Avant-garde music movement of the Sixties,[8] sometimes referred to as the New Polish School. In 1977 Kilar was one of the founding members of the Karol Szymanowski Society, based in the mountain town of Zakopane. Kilar chaired the Katowice chapter of the Association of Polish Composers for many years and from 1979 to 1981 was vice chair of this association's national board. He was also a member of the Repertoire Committee for the "Warsaw Autumn" International Festival of Contemporary Music. In 1991 Polish filmmaker Krzysztof Zanussi made a biographical film about the composer titled Wojciech Kilar.

Having received critical success as a classical composer, Kilar scored his first domestic film in 1959, and went on to write music for some of Poland's most acclaimed directors, including Krzysztof Kieślowski, Krzysztof Zanussi, Kazimierz Kutz and Andrzej Wajda. He worked on over 100 titles in his home country, including internationally recognised titles such as Bilans Kwartalny (1975), Spirala (1978), Constans (1980), Imperativ (1982), Rok Spokojnego Słońca (1984), and Życie za Życie (1991), plus several others in France and across other parts of Europe. He made his English-language debut with Francis Ford Coppola's adaptation of Dracula. His other English language features — Roman Polanski's trio Death and the Maiden (1994), The Ninth Gate (1999) and The Pianist (2002), and Jane Campion's The Portrait of a Lady (1996) — were typified by his trademark grinding basses and cellos, deeply romantic themes and minimalist chord progressions.

In addition to his film work, Kilar continued to write and publish purely classical works, which have included a horn sonata, a piece for a wind quintet, several pieces for chamber orchestra and choir, the acclaimed Baltic Canticles, the epic Exodus (famous as the trailer music from Schindler's List and the main theme of Terrence Malick's Knight of Cups), a Concerto for Piano and Orchestra dedicated to Peter Jablonski, and his major work, the September Symphony (2003).[8]

Having abandoned Avant-garde music technical means almost entirely, he continued to employ a simplified musical language, in which sizable masses of sound serve as a backdrop for highlighted melodies. This occurs in those compositions that reference folk music (especially Polish Highlander Gorals folk melodies) and in patriotic and religious pieces.

Illness and death

During the summer of 2013, Kilar manifested signs of poor health, such as fainting and elevated blood pressure, but attributed those symptoms to his heart problems. However, in September he fell while on the street. He was admitted to a hospital, where he was diagnosed with a brain tumor, though news of his illness was only publicly released after his death. He underwent a successful surgery to remove the tumor, which caused no serious side–effects; Kilar was very optimistic and continued to work after the operation.[9] In addition, he underwent radiotherapy for six weeks, a process which left 81-year-old Kilar physically exhausted.[10][11][12]

In early December 2013, Kilar left the hospital to return to his residence in Katowice. As he did not have any children, he was taken care of by his niece.[12] He was also regularly visited by a Catholic priest and received the Holy Communion twice during the Christmas season. His condition deteriorated on 28 December and on the morning of Sunday, 29 December 2013, Kilar died.[10] Following the cremation of his body, Kilar's funeral was held on 4 January 2014 at the Cathedral of Christ the King in Katowice. After the service, his ashes were laid to rest alongside those of his wife.[13]

Works

Later in life, Kilar composed symphonic music, chamber works and works for solo instruments. January 2001 saw the world premiere of his Missa pro pace (composed for a full symphony orchestra, mixed choir and a quartet of soloists) at the National Philharmonic in Warsaw. The work was written to commemorate the Warsaw Philharmonic's centennial. In December 2001, it was performed again in the Paul VI Audience Hall in the presence of Pope John Paul II.[14] His 1984 composition Angelus was used in the motion picture City of Angels; Orawa, from 1988, found its use in the Santa Clara Vanguard's 2003 production, "Pathways".

For most of his life, Kilar's output was dominated by music for film with a small but steady stream of concert works. Post 2000, he turned to "music of a singular authorship". Since his 2003 September Symphony, (Symphony No.3), a four-movement full scale symphony written for the composer's friend Antoni Wit, Kilar returned to absolute music. September Symphony was the first symphony by the composer since 1955's Symphony for Strings (along with another student symphony) and Kilar considered it his first mature symphony (composed at age 71).

From 2003, Kilar had been steadily producing large scale concert works. His Lament (2003) for unaccompanied mixed choir, his Symphony No.4 Sinfonia de Motu (Symphony of Motion) from 2005 written for large orchestra, choir and soloists, his Magnificat Mass from 2006, Symphony No.5 Advent Symphony from 2007 and another large mass, Te Deum premiered in November 2008.[8] Kilar was quoted as saying that he believed he had discovered the philosopher's stone, and that "there was nothing more beautiful than the solitary sound or concord that lasted eternally, that this was the deepest wisdom, nothing like our tricks with sonata allegros, fugues, and harmonics." [15] Kilar's works have been performed by several major international orchestras, including the Philadelphia Orchestra, the Cleveland Orchestra, and the New York Philharmonic.

Awards

.jpg.webp)

Wojciech Kilar received numerous awards for his artistic activity and achievements, including prizes from the Lili Boulanger Foundation in Boston (1960), the Minister of Culture and Art (1967, 1975), the Association of Polish Composers (1975), the Katowice province (1971, 1976, 1980), and the city of Katowice (1975, 1992).[16] He was also awarded the First Class Award of Merit of the Polish Republic (1980), the Alfred Jurzykowski Foundation Prize in New York City (1984), the Solidarity Independent Trade Union Cultural Committee Arts Award (1989), the Wojciech Korfanty Prize (1995), the "Lux ex Silesia" Prize bestowed by the Archbishop and Metropolitan of Katowice (1995), and the Sonderpreis des Kulturpreis Schlesien des Landes Niedersachsen (1996).

Kilar's film scores have also won him many honors. He received the best score award for the music to Ziemia obiecana (The Promised Land) (dir. Andrzej Wajda) at the Festival of Polish Films in Gdańsk in 1975. This was followed by the Prix Louis Delluc, which Kilar was awarded in 1980 for the music to an animated film titled Le Roi et l'Oiseau / The King and the Mockingbird, (dir. Paul Grimault). One year later he collected an award at the Cork International Film Festival for the music to Papież Jan Pawel II / Pope John Paul II / Da un paese lontano: Papa Giovanni Paulo II (dir. Krzysztof Zanussi).

Perhaps his greatest success came with his score to Francis Ford Coppola's Dracula, for which Kilar shared the 1993 ASCAP Award from the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Producers in Los Angeles (along with 7 other people and 5 other movies),[17] and was also nominated for the Saturn Award for Best Music in a science fiction, fantasy, or horror film in San Francisco in 1993.[1]

In 2003, he won the César Award for Best Music written for a film, for The Pianist, at France's 28th César Awards Ceremony in 2003,[2] for which he also received a BAFTA nomination.[3] On this movie's published soundtrack he composed "Moving to the Ghetto Oct. 31, 1940" (duration: 1 minute 52 seconds), with the other 10 tracks being works by Frédéric Chopin; the music in the actual movie also includes pieces by Beethoven and Bach.

The Polish State Cinema Committee honored Kilar with a lifetime achievement award in 1991, while in 1976 he was decorated with the Cavaliers' Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta. In November 2008 Kilar was awarded the Grand Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta.

List of major awards

- The French Lili Boulanger Prize for composition (1960)

- The Polish Ministry of Culture and Arts Award (1967 and 1976)

- The Polish Composers Union Award (1975)

- The French Prix Louis Delluc (1980)

- The Alfred Jurzykowski Foundation Award (1984, USA)

- The Polish Cultural Foundation Award (2000)

- Co-Winner (with 7 other people and 5 other movies) of the 1993 ASCAP Award from the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Producers in Los Angeles for his score for the Francis Ford Coppola horror film Bram Stoker's Dracula.[17]

- Nominated for the Saturn Award for Best Music in a science fiction, fantasy, or horror film, for Bram Stoker's Dracula (San Francisco, 1993)[1]

- Winner of the César Award for Best Music written for a film, for The Pianist, at France's 28th César Awards Ceremony in 2003[2]

- Nominated for the Anthony Asquith Award for Film Music, for The Pianist, at Britain's 2003 BAFTA Awards[3]

Film music

- Nikt nie woła (Nobody's calling, 1960)

- Milczące ślady (1961)

- Spotkanie w "Bajce" (Café From The Past, 1962)

- Tarpany (Wild Horses, 1962)

- Głos z tamtego świata (Voice from beyond, 1962)

- Milczenie (Silence, 1963)

- Pięciu (1964)

- Three Steps on Earth (Trzy kroki po ziemi, 1965)

- Salto (Somersault, 1965)

- Marysia i Napoleon (1966)

- Piekło i niebo (Hell and heaven, 1966)

- Bicz Boży (God's Whip, 1967)

- Sami swoi (1967)

- Westerplatte (1967)

- The Doll (Lalka, 1968)

- Salt of the Black Earth (Sól ziemi czarnej, 1969)

- The Structure of Crystal (Struktura kryształu, 1969)

- Family Life (Życie rodzinne, 1970)

- The Cruise (Rejs, 1970)

- Lokis. A Manuscript of Professor Wittembach (Lokis. Rękopis profesora Wittembacha, 1970)

- Pearl in the Crown (Perla w Koronie, 1971)

- Bolesław Śmiały (King Boleslaus the Bold, 1972)

- The Illumination (Iluminacja, 1973)

- Opętanie (Possession, 1973)

- Zazdrość i Medycyna (1973)

- Hubal (1973)

- A Woman's Decision (Bilans Kwartalny, 1974)

- The Promised Land (Ziemia obiecana, 1974)

- Smuga cienia (The Shadow Line, 1976)

- Trędowata (1976)

- Jarosław Dąbrowski (1976)

- Ptaki ptakom (Bords to Birds, 1977)

- Camouflage (Barwy ochronne, 1977)

- Spiral (Spirala, 1978)

- Rodzina Połanieckich (1978, TV series)

- David (1979)

- The King and the Mockingbird (Le Roi et l'Oiseau, 1980)

- The Constant Factor (Constans, 1980)

- From a Far Country (1981)

- Blind Chance (Przypadek, 1982)

- Imperative (Imperatyw, 1982)

- A Year of the Quiet Sun (Rok spokojnego słońca, 1984)

- Power of Evil (Paradigma, 1985)

- A Chronicle of Amorous Accidents (Kronika wypadków miłosnych, 1986)

- Salsa (1988)

- Wherever You Are... (1988)

- Inventory (Stan posiadania, 1989)

- Korczak (1990)

- Napoléon et l'Europe (1991, TV miniseries)

- Life for Life: Maximilian Kolbe (Życie za życie. Maksymilian Kolbe, 1991)

- Bram Stoker's Dracula (1992)

- The Silent Touch (1992)

- Śmierć jak kromka chleba (1994)

- Death and the Maiden (1994)

- Faustina (1995)

- Legenda Tatr (1995)

- At Full Gallop (Cwał, 1996)

- The Portrait of a Lady (1996)

- Deceptive Charm (1996)

- Our God's Brother (1997)

- The Truman Show (1998) (parts from Requiem Father Kolbe)

- The Ninth Gate (1999)

- Pan Tadeusz (1999)

- Life as a Fatal Sexually Transmitted Disease (2000)

- The Supplement (2002)

- The Pianist (2002)

- The Revenge (Zemsta, 2002)

- Persona Non Grata (2005)

- We Own the Night (2007)

- Black Sun (2007)

- Two Lovers (2008)

- Welcome (2009)

Concert music

Orchestral

- Small Overture (1955), for the Youth Festival, 1955

- Symphony for Strings (Symphony No. 1, 1955)

- Ode Béla Bartók in memoriam, for violin, brass, and percussion (1956)

- Riff 62 (1962)

- Generique (1963)

- Springfield Sonnet (1965)

- Krzesany, for orchestra (1974)

- Kościelec 1909, for orchestra (1976)

- Orawa, for string orchestra (1986)

- Choralvorspiel (Choral Prelude), for string orchestra, (1988)

- Requiem Father Kolbe, for symphony orchestra (1994)

- Symphony No. 3 "September Symphony" for orchestra (2003)

- Ricordanza (2005)

- Uwertura uroczysta [Solemn Overture] for orchestra (2010)

Orchestral, with instrumental and vocal soloists or accompaniment

- Symphony Concertante, for piano and orchestra (Symphony No. 2, 1956)

- Prelude and Christmas Carol, for four oboes and string orchestra (1972)

- Bogurodzica, for mixed choir and orchestra (1975)

- Hoary Fog (Siwa mgła), for baritone and orchestra (1979)

- Exodus, for mixed choir and orchestra (1981)

- Victoria, for mixed choir and orchestra (1983)

- Angelus, for symphony orchestra, soprano, and mixed choir (1984)

- Piano Concerto No.1 (1996)

- Missa Pro Pace, for orchestra, chorus, and soloists (2000)

- Symphony No. 4 "Sinfonia de Motu" (Symphony of Motion), for orchestra, chorus, and soloists (2005)

- Magnificat, for orchestra, chorus, and soloists (2007)

- Symphony No. 5 "Advent Symphony", for orchestra, chorus, and soloists (2007)

- Te Deum, for orchestra, chorus, and soloists (2008)

- Veni Creator, for mixed chorus and strings (2008)

- Piano Concerto No.2 (2011)

Choral

- Lament, for mixed unaccompanied choir (2003)

- Paschalis Hymn for chorus (2008)

Chamber

- Flute Sonatina (1951)

- Woodwind Quintet (1952)

- Horn Sonata (1954)

- Training 68, for clarinet, trombone, cello and piano (1968)

- Orawa, arr. for 8 Cellos

- Orawa, arr. for 12 Saxophones (2009)

Piano

Numerous solo piano pieces

Symphonic poems

Krzesany

Krzesany is a symphonic poem completed in 1974.

The premiere of the poem took place in Warsaw during the "Warsaw Autumn" International Festival of Contemporary Music on September 24, 1974. The composer has dedicated a piece to the National Philharmonic. The piece is a reference to the folk music of Podhale. Originally Krzesany is a folk dance from the Podhale region. The work was completed on July 14, 1974. It was performed for the first time on September 24, 1974. The poem is a one-movement piece. Along with Kościelec 1909, Hoary Fog and Orawa, Krzesany is a kind of "Kilarian Tatra polyptych".[18][19]

Kościelec

Kościelec 1909 is a symphonic poem completed in 1976.

The premiere took place in Warsaw on November 5, 1976. Wojciech Kilar composed a piece on the occasion of the 75th anniversary of the National Philharmonic in Warsaw and the 100th anniversary of the birth of Mieczysław Karłowicz. The composition was dedicated to the conductor Witold Rowicki. Along with Krzesany, Hoary Fog and Orawa, Kościelec 1909 is a kind of "Kilarian Tatra polyptych". The pieces refer to the tradition of Podhale music. The composer distinguished three sections-themes: tema della montagna (mountain theme), tema dell’abisso chiamante (abyss theme) and tema del destino (fate theme).[18] The piece was inspired by the tragic death of the Polish romantic composer Mieczysław Karłowicz. Karłowicz died on February 8, 1909, in a snow avalanche at the foot of Mały Kościelec in the Tatra Mountains.[20]

Hoary Fog

Hoary Fog (Polish title: Siwa mgła) is a vocal-symphonic poem completed in 1979.

It was based on the song of the Podhale highlanders. The author dedicated the piece to the opera singer Andrzej Bachleda-Curuś. Along with Krzesany, Kościelec 1909 and Orawa, Hoary Fog is a kind of "Kilarian Tatra polyptych". The pieces refer to the tradition of Podhale music.[18] The music is accompanied by the singing of a baritone. The text is a traditional Polish highlander song. It is a one-movement piece. The world premiere took place in Bydgoszcz on October 14, 1979. The baritone part was then performed by Andrzej Bachleda-Curuś, the Symphony Orchestra of the Kraków Philharmonic was conducted by Jerzy Katlewicz.[21]

Orawa

Orawa is a symphonic poem for chamber string orchestra completed in 1986.

The premiere of the poem took place in Zakopane on March 10, 1986. The Polish Chamber Orchestra was conducted by Wojciech Michniewski. This is the fourth piece by Kilar referring to the tradition of Podhale music. Along with Kościelec 1909, Hoary Fog and Krzesany, Orawa is a kind of "Kilarian Tatra polyptych". There are arrangements for a string quartet, twelve saxophones, an accordion trio, eight cellos and others.[18][22][23]

Political views

During the 2007 election campaign for the National Assembly of the Republic of Poland, Wojciech Kilar made a number of statements of his support of the Law and Justice party.[24]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy & Horror Films, USA - Awards for 1993". IMDb. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy & Horror Films, USA; Date: June 8, 1993 Location: USA; Awards for 1993 - Saturn Award ... Best Music ... Nominees: Dracula: Wojciech Kilar

- 1 2 3 "PALMARES 2003 - 28 TH CESAR AWARD CEREMONY". Académie des arts et techniques du cinéma (fr). Retrieved January 2, 2014.

Best Music written for a film: Wojciech Kilar - Le Pianiste

- 1 2 3 "Bafta Film Awards - Film: Anthony Asquith Award for Original Film Music in 2003". BAFTA. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

Nominees: ... The Pianist: Wojciech Kilar

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Wojciech Kilar". Adam Mickiewicz Institute. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ↑ "Prywatny sukces Kilara – Muzyka – Adonai.pl".

- ↑ "Basia prowadziła mnie do Boga jak Maryja". 23 December 2009.

- ↑ "Wojciech Kilar Biography Page 2". Wojciech Kilar Official Website. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

While in Kraków he studied piano with Maria Bilińska-Riegerowa and took private lessons in harmony with Artur Malawski.In 1948 he went to Katowice. There he finished his music middle school in Władysława Markiewiczówna's class and the State Higher School of Music in the class of Bolesław Woytowicz (piano and composition).

- 1 2 3 "Wojciech Kilar – Pełna baza wiedzy o muzyce – magazyn Culture.pl – Culture.pl".

- ↑ Tomczuk, Jacek (17 January 2014). "Wojciech Kilar i jego muzyka życia". Newsweek Polska. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- 1 2 "Od pół roku Kilar zmagał się z nowotworem". Tygodnik Idziemy. 29 December 2013. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ↑ "Joanna Wnuk-Nazarowa o Wojciechu Kilarze: Kochało go Hollywood, pozostał w Katowicach". Gazeta.pl. 29 December 2013.

- 1 2 Watoła, Judyta (29 December 2013). "Wojciech Kilar nie żyje. Zmarł w wieku 81 lat". Gazeta.pl.

- ↑ "Oscar-winning composer Wojciech Kilar laid to rest in state funeral". The New Zealand Herald. 5 January 2013.

- ↑ "Peace concert". The Deseret News. 8 December 2001. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- ↑ Pmrc Sites: Wojciech Kilar Archived 2005-10-25 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Polish culture".

- 1 2 "ASCAP Film and Television Music Awards (1993)". IMDb. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

ASCAP Film and Television Music Awards; Date: April 21, 1993 Location: USA; Awards for 1993 - ASCAP Award ... Top Box Office Films - WINNERS:

Aladdin: Howard Ashman, Alan Menken, Tim Rice

Dracula: Wojciech Kilar

The Hand That Rocks the Cradle: Graeme Revell

Patriot Games: James Horner

Sister Act: Marc Shaiman

Wayne's World: J. Peter Robinson - 1 2 3 4 "Krzesany – poemat symfoniczny (dyr. Jan Krenz)" (in Polish). ninateka.pl. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ↑ "Wojciech Kilar. Krzesany" (in Polish). pwm.com.pl. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ↑ "Wojciech Kilar, "Kościelec 1909"" (in Polish). culture.pl. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ↑ "Siwa mgła na baryton i orkiestrę (wyk. Andrzej Bachleda)" (in Polish). ninateka.pl. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ↑ "Orawa na kameralną orkiestrę smyczkową (opracowanie na kwartet smyczkowy)" (in Polish). ninateka.pl. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ↑ ""Orawa" Wojciecha Kilara" (in Polish). www.polskaorawa.pl. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ↑ "Kilar szefem honorowego komitetu PiS".

External links

- Official website (English)

- Obituary in The Independent by Marcus Williamson

- Wojciech Kilar at IMDb

- Composer's website

- Kilar at the Polish Music Center

- Wojciech Kilar at Culture.pl

- Kilar Orawa on YouTube, performed by The Karol Szymanowski Youth Symphony Orchestra

- Kilar Orawa on YouTube, performed by The Baltic Sea Youth Philharmonic

- Kilar Krzesany on YouTube, performed by The Karol Szymanowski Youth Symphony Orchestra

- Kilar Krzesany on YouTube, performed by The Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra, Katowice

- Kościelec 1909 on YouTube, performed by Warsaw National Philharmonic Orchestra

- Hoary Fog on YouTube, performed by Warsaw National Philharmonic Orchestra