Wolfdietrich Schnurre | |

|---|---|

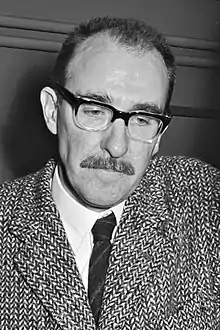

Schnurre in 1967 | |

| Born | 22 August 1920 Frankfurt am Main, German Reich |

| Died | 9 June 1989 (aged 68) Kiel, West Germany |

| Resting place | Waldfriedhof Zehlendorf, Berlin |

| Occupation | Author |

| Language | German |

| Genre | Rubble literature |

| Notable works | Das Begräbnis |

| Children | 2 |

Wolfdietrich Schnurre (22 August 1920 – 9 June 1989) was a German writer. Best known for his short stories, he also wrote tales, diaries, poems, radio plays, and children's books. Born in Frankfurt am Main, and later raised in Berlin-Weißensee, he grew up in a lower-middle class family and did not receive a post-secondary education. He served in Nazi Germany's army from 1939 until 1945, when he escaped from a prisoner camp after having been arrested for desertion. He was briefly imprisoned by British troops; after his release he returned to Germany in 1946 and began to write commercially.

Schnurre's experiences during the Second World War informed the themes of his writings, which often discuss guilt and moral responsibility; though influenced by his socialist political views, his works aim at ethical activation of the reader and not political activism. He is sometimes considered a representative of the rubble literature movement, a short period in German literary history during which many authors, often former soldiers, sought to re-establish German literature after the incisive events of the war. He was a founding member of the literary association Gruppe 47, and his short story Das Begräbnis (The Funeral), which describes God's death and burial, was read at the group's first meeting in 1947. Guilt, remembrance and war experiences are central themes in all of his major works; short story collections Als Vaters Bart noch rot war (When father's beard was still red) and Als Vater sich den Bart abnahm (When father shaved his beard off) recount the experiences of the narrator and his father in lower-class Berlin during the period of the rise of Nazism, while his sole novel, Ein Unglücksfall (A misfortune, An accident) explores themes of guilt and responsibility surrounding the persecution of Jews under Nazi rule. Among his other major works is Der Schattenfotograf (The shadow photographer), a discontiguous collection of various texts.

He received many awards for his literary work, including the Immermann-Preis in 1959, the Bundesverdienstkreuz in 1981, and the Georg Büchner Prize in 1983. Schnurre remained a highly active writer from the 1940s through the 1970s, but his literary output decreased after he moved to Felde in the early 1980s. In 1989, he died of heart failure in Kiel.[1]

Early life

Schnurre was born in Frankfurt am Main on 22 August 1920 to Otto and Erna Schnurre (née Zindel). Schnurre was raised by his father after Erna Schnurre left the family during his early childhood and remarried.[2] A student at the time of Schnurre's birth, Otto Schnurre earned his income as a factory worker and graduated with a PhD in ornithology in 1921.[3] The two lived in the Oberrad and Eschersheim districts of Frankfurt from 1920 to 1928. Schnurre frequently fell ill during childhood and was repeatedly placed in the care of Christian children's homes; traumatic experiences there contributed to his scepticism of religion in later life.[4]

In 1934, Schnurre and his father moved to Berlin-Weißensee, where Otto Schnurre had found a job as deputy head librarian of the Berlin City Library. Schnurre attended a secular state school in Berlin until 1934, when he switched to a Humanistisches Gymnasium.[5] Schnurre, who was relatively independent from an early age due to his father being preoccupied with work and affairs with women, grew up in a lower- to lower-middle-class social environment. He later characterised his experiences at school as largely shielded from National Socialist ideological influences, stating that his teachers were largely socialists, communists and proponents of the Weimar Democracy.[6]

Military service and return

Schnurre served in the army of Nazi Germany from 1939 until 1945.[7] The exact circumstances of his entry into service are unknown; according to his own version of events, which he recounted in a 1989 interview, he was conscripted into the Reich Labour Service in 1939 and volunteered for the Wehrmacht because he anticipated imminent conscription and was able to choose his branch of service this way.[8]

During his military service, which included postings in Poland, Germany and France,[9] Schnurre was repeatedly arrested and assigned to Strafkompanien. The exact reasons for these disciplinary actions are unknown, though at least some of them can be attributed to Schnurre's refusal to comply with the Wehrmacht's prohibition on writing. Schnurre unsuccessfully attempted desertion in 1945, and was arrested and sent to a prisoner camp. In April 1945, he successfully escaped the camp and fled to Westphalia. Schnurre was captured by British troops and briefly imprisoned near Paderborn. He had married during the war; the couple had a son who was born in October 1945.[10]

Following his release from British captivity, Schnurre worked on a farm and later returned to East Berlin in 1946, where he became a trainee at Ullstein Verlag, and wrote as an art, film, and literature critic for publications that had been licensed by the American occupying powers. His writing for Western publications led to conflicts with the Soviet authorities in East Berlin, leading to Schnurre moving to West Berlin two years later.[11]

Later life and literary career

Schnurre's war experiences had made him uncomfortable with working under superiors, so he quit work as a critic and became a freelance writer for radio stations and print publications in 1950. He remarried in 1952.[12]

Schnurre was a founding member of the literary association Gruppe 47 and his short story Das Begräbnis (The funeral) was the first piece of literature read at the group's initial meeting.[11] He became a member of the Federal Republic of Germany's branch of PEN in 1958,[11] but left in 1961 to protest against PEN's silence after the construction of the Berlin Wall, which had separated him from his father.[13] In 1964, he developed severe polyneuritis that left him completely paralysed for more than a year,[14] and his recovery was slow.[1] The costs of his extended hospital stay also led to financial troubles.[15]

In 1965, his second wife died of suicide after 13 years of marriage. He remarried a year later; the couple adopted a son in 1974.[10] In 1981, he published his first and only novel, Ein Unglücksfall (An accident, A misfortune).[1] Schnurre moved to Felde in the early 1980s, leaving his family behind. During this time, his literary output decreased as Schnurre spent time in nature – particularly watching birds – instead.[10] He died of heart failure in Kiel on 9 June 1989 and was buried in the Waldfriedhof Zehlendorf cemetery in Berlin.[16] He left behind detailed instructions for his funeral, requesting that there be no speech, sermon or music. Instead, he asked for "someone with a good voice" to read the "most beautiful story in the world", Unverhofftes Wiedersehen ("Unexpected reunion") by Johann Peter Hebel, and that the guests engage in small talk "at the grave, or at least at the cemetery".[17]

Themes

Schnurre was highly active as an author and published more books than any other German author in the period between 1945 and 1972.[1] His large and diverse[18] body of works has been described as "hard to bring down to a catchy formula" by biographer Katharina Blencke.[19] Despite this diversity, the Second World War consistently emerges as a fundamental thematic complex in Schnurre's works.[20] While Schnurre had wanted to become an author since his childhood, he published little before 1945. The war catalysed his desire to write and heavily influenced the themes of his work.[21] Forgetting and remembrance, death, violence, and especially guilt were frequent topics of his writings.[22] Blencke has stated that Schnurre's "fundamental feeling of guilt became the crucial driver of his writing",[23] and that his own memory served as the most important source of literary material.[24] Schnurre is sometimes characterised as an exponent of the rubble literature movement,[25] a short (1945 – c. 1950) period in German literary history during which some German authors – often former soldiers – sought to capture the psychological and physical destruction they encountered after their return and to re-establish German literature by explicitly distancing themselves from the language and ideology of Nazi Germany.[26]

Schnurre was uncomfortable with political labels and never joined a party,[27] but expressed support for socialist ideas, specifically for the ideology of the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany, a short-lived offshoot of the Social Democratic Party of Germany that had dissolved long before he reached adulthood.[28] Unlike many other German authors of the time, however, he did not intend for his writings to function as a vehicle for political agitation, but primarily as a means for "moral-ethical activation of the reader".[29] He wanted to "write as a contemporary"[30], and explicitly intended for his stories to be read by "average" and young readers.[31] In his acceptance speech for the Georg Büchner Prize of 1983, he described his approach to writing:

... I am otherwise of the opinion that the author, in the interest of the balance of his story, does not have the right to solve problems. He has to perceive them, rip them open, push his actors into them.

... ich ansonsten der Ansicht bin, daß der Literat, im Interesse der Ausgewogenheit seiner Geschichte, kein Recht hat, Probleme zu lösen. Er hat sie wahrzunehmen, aufzureißen, seine Akteure hineinzustoßen.

Major works

Das Begräbnis

In Das Begräbnis (The funeral), Schnurre tells the story of a man who unexpectedly receives a letter containing an obituary that informs him of God's death. He decides to attend the funeral; there are only seven other people in attendance, including two gravediggers and a priest who struggles to recall the name of the deceased, calling him "Klott or Gott or something like that".[32] Schnurre employs colloquial language and uses ellipsis and parataxis as literary devices, making short, simple sentences that are strung together without use of conjunctions.[33] Das Begräbnis, whose central themes are guilt and the loss of faith and hope during World War II,[34] was completed in 1946[35] and first published in the magazine Ja. Zeitung der jungen Generation (Yes. Newspaper of the young generation) two years later.[36] According to his own account, Schnurre had "written the story at night on an upturned crib", with revisions resulting in a total of twelve or thirteen different versions.[37] It was read both at the first and the last meeting of the Gruppe 47.[38]

Als Vaters Bart noch rot war and Als Vater sich den Bart abnahm

Als Vaters bart noch rot war (When father's beard was still red) and Als Vater sich den Bart abnahm (When father shaved his beard off) are collections of short stories about the experiences of the narrator and his father in the harsh world of 1920s and 1930s lower-class Berlin, which is nonetheless presented in a positive light. Because they take place against the backdrop of Adolf Hitler's rise to power and an increasingly precarious political environment in Germany, the stories are often political, and frequently explore moral questions. Als Vaters Bart noch rot war was published in 1958; the second volume followed in 1995, after Schnurre's death, and contains stories whose completion dates range from the 1950s to the year of Schnurre's death. They are among Schnurre's more popular works, with some of the stories from the first volume frequently being included in school books.[39]

Der Schattenfotograf

Der Schattenfotograf. Aufzeichnungen ("The Shadow Photographer. Records"), published in 1978, is a collection of texts that take various literary forms. Biographer Katharina Blencke identifies a total of nine types of texts, including diary entries, poems, short stories and letters.[40] The texts touch on various aspects of Schnurre's personal life, including the suicide of his second wife,[41] his childhood,[42] and his feeling of being an inadequate father to his adoptive son owing to the disabilities he had acquired following his polyneuritis.[43] At the time of publication, Schnurre had already faded into relative obscurity. To his surprise, and despite the unusual composition of the book, it was well-received by both critics and readers and became a commercial success.[44]

Ein Unglücksfall

In 1981, Schnurre published Ein Unglücksfall (A misfortune, An accident). The story takes place in 1959 and is written from the perspective of Berlin rabbi Lovinski who accompanies German glazier Goschnik on his deathbed after the glazier has an accident while working on a mizrah window as part of the reconstruction of a destroyed synagogue; the rabbi had helped him get the job. While inserting the window, his thoughts had wandered to Avrom and Sally Grünbaum, a Jewish couple who had served as his substitute parents during his childhood. During the Second World War, he had hidden them in his basement to protect them from persecution. After being drafted into the Army and deserting, he had returned and found the couple dead by suicide. Goschnik feels guilty for their deaths and realises that he had tried to redeem himself by working for the synagogue. The realisation that this is a futile effort made him disgusted with his own reflection in the window glass; he smashed it and fell to the ground. He recounts this to the rabbi on his deathbed, believing that Lovinski is in fact Avrom Grünbaum. Upon Goschnik's death, the rabbi is also plagued by guilt for playing along and pretending to be Grünbaum, and feels that he is responsible for the death because he had employed Goschnik. The guilt drives him to give up his job as a rabbi and – in a parallel to Schnurre – write down his thoughts.[45]

While he had made eight previous attempts at writing novels and published contiguous short story collections like Als Vaters Bart noch rot war (subtitled "a novel in stories"), Ein Unglücksfall was Schnurre's only published novel.[46] The book was met with negative reviews and low sales figures, in stark contrast to the positive reception of Der Schattenfotograf. Contemporary reviewers criticised the construction of the story as artificial, and the colloquial language used in the book as inauthentic and irritating. Later scholarship takes a more positive view of the book, and authors have proposed a number of factors that may have contributed to the book's negative reception by critics and readers, including preconceived notions on the part of the critics, deficiencies in Germany's Culture of Remembrance, and competing works that were released at the same time.[47]

Reception and awards

Schnurre's early works were widely received and found their way into contemporary German school textbooks.[48] He also held frequent and successful public readings for varied audiences.[31] Despite this early success, he faded into relative obscurity in later life and is less present in public discourse than other important German writers.[49] Scholars have proposed a number of factors that may have contributed to this, such as the diversity of his work which made him hard to categorise as an author, the declining popularity of short stories as an art form following the immediate post-war period, and the inherently small print runs and limited reception of poetry and children's literature.[50]

Despite his diminishing presence in public discourse, Schurre received several awards for his works, including in his late years. Among those awards were the Immermann-Preis (1959), the Georg Marckensen Literature Award (1962), the Federal Cross of Merit (Bundesverdienstkreuz, 1981), the Literature Award of the City of Cologne (1982), the Georg Büchner Prize (1983) and the Culture Award of the City of Kiel (1989).[51]

Selected works

Some of Schnurre's works include:[52]

- Das Begräbnis, 1947

- Die Rohrdommel ruft jeden Tag, 1950

- Sternstaub und Sänfte. Aufzeichnungen des Pudels Ali, 1953

- Als Vaters Bart noch rot war, 1958

- Eine Rechnung, die nicht aufgeht, 1958

- Das Los unserer Stadt, 1959

- Man sollte dagegen sein, 1960

- Berlin. Eine Stadt wird geteilt, 1962

- Schreibtisch unter freiem Himmel, 1964

- Die Zwengel, 1967

- Klopfzeichen, 1978

- Der Schattenfotograf, 1978

- Ein Unglücksfall, 1981

Notes and references

- 1 2 3 4 Hüfner 2012.

- ↑ Schult 2020, p. 439; Hock 2017.

- ↑ Hock 2017.

- ↑ Hock 2017; Blencke 2003, p. 59.

- ↑ Blencke-Dörr 2007; Blencke 2003, pp. 59–61; Hock 2017.

- ↑ Blencke 2003, pp. 59–62.

- ↑ Blume, Haunhorst & Zündel 2016.

- ↑ Blencke 2003, pp. 65f.

- ↑ Roberts 2005, p. 206.

- 1 2 3 Schult 2020, p. 440.

- 1 2 3 Blencke-Dörr 2007.

- ↑ Linder 2014; Schult 2020, p. 440; Blencke 2003, p. 69; Hüfner 2012.

- ↑ Blencke 2003, p. 35; Schult 2020, p. 440.

- ↑ Schneider 2010.

- ↑ Bauer 1996, p. 179.

- ↑ Hock 2017; Linder 2014.

- ↑ Schnurre's exact words were quoted in contemporary obituaries and are reprinted in Linder 2014: "Am Grab keine Predigt, keine Ansprache, keine Musik. Aber jemand mit guter Stimme soll die schönste Geschichte der Welt am offenen Grab vorlesen. Sie heißt 'Unverhofftes Wiedersehen', und es hat sie Johann Peter Hebel geschrieben. Ich bitte darum, schon am Grab, auf jeden Fall noch auf dem Friedhof, wieder Alltagsgespräche zu führen."

- ↑ Blencke 2003, p. 467; Bauer 1996, p. 12.

- ↑ Blencke 2003, p. 467.

- ↑ Bauer 1996, p. 18.

- ↑ Blencke 2003, p. 64; Bauer 1996.

- ↑ Schult 2020, p. 438; Boyken & Immer 2020, pp. 126–133.

- ↑ "[...] Schnurre, dessen fundamentales Schuldgefühl zum entscheidenden Schreibantrieb wurde", Blencke 2003, p. 72

- ↑ Blencke 2003, p. 74.

- ↑ Schult 2020, p. 438; Boyken & Immer 2020, pp. 127.

- ↑ Dittmann 2016.

- ↑ Boyken & Immer 2020, p. 128.

- ↑ Blencke 2003, pp. 132–137.

- ↑ "Nicht die politische Agitation steht für Schnurre im Vordergrund, sondern die moralisch-ethische Aktivierung der Lesenden.", Boyken & Immer 2020, p. 128

- ↑ "Schreiben als Zeitgenosse", Blencke-Dörr 2007

- 1 2 Blencke 2003, p. 38.

- ↑ "Klott oder Gott oder so etwas", Schnurre 1960, p. 23

- ↑ Bauer 1996, p. 63; Boyken & Immer 2020, p. 127.

- ↑ Bauer 1996, pp. 61–65.

- ↑ Blencke 2003, p. 198; Schnurre 1960, p. 28.

- ↑ Boyken & Immer 2020, p. 127.

- ↑ "nachts auf einer umgedrehten Krippe geschrieben", Adelhoefer 1998

- ↑ Bauer 1996, pp. 60f.

- ↑ Blencke 2003, pp. 203–208.

- ↑ Blencke 2003, pp. 235–238.

- ↑ Bauer 1996, p. 185.

- ↑ Blencke 2003, p. 235.

- ↑ Bauer 1996, p. 181.

- ↑ Blencke 2003, pp. 230–233.

- ↑ Blencke 2003, pp. 251–252; Bauer 1996, pp. 88–89.

- ↑ Blencke 2003, p. 248.

- ↑ Blencke 2003, pp. 252–257.

- ↑ Schult 2020, p. 437.

- ↑ Blencke 2003, p. 27.

- ↑ Blencke 2003, pp. 27–29.

- ↑ Blencke-Dörr 2007; Hock 2017.

- ↑ This selection is based on works that are frequently mentioned in secondary and tertiary sources, see e.g. Blencke-Dörr 2007, Hock 2017, Blume, Haunhorst & Zündel 2016, Chisholm 1980, and Garland & Garland 1997.

Bibliography

- Adelhoefer, Mathias (1990). Wolfdietrich Schnurre: Ein deutscher Nachkriegsautor [Wolfdietrich Schnurre: A German Post-war Author] (in German). Pfaffenweiler: Centaurus. ISBN 978-3-89085-441-0. OCLC 22891488.

- Adelhoefer, Mathias (1998). "Ein Gespräch mit Wolfdietrich Schnurre - Berlin, 1986" [A conversation with Wolfdietrich Schnurre – Berlin, 1986]. Mathias Adelhoefer (in German). Archived from the original on 17 January 2008. Retrieved 4 March 2021. Online version of an interview originally published in Adelhoefer 1990, pp. 94–105.

- Bauer, Iris (1996). Ein schuldloses Leben gibt es nicht. Das Thema "Schuld" im Werk von Wolfdietrich Schnurre [There is no life free from guilt. The topic of guilt in the work of Wolfdietrich Schnurre] (in German). Paderborn: Igel-Verlag. ISBN 3-89621-041-6. OCLC 36865889.

- Blencke, Katharina (2003). Wolfdietrich Schnurre. Eine Werkgeschichte [Wolfdietrich Schnurre. A history of his writings]. Frankfurt am Main: Europäischer Verlag der Wissenschaften. ISBN 978-3-631-51259-3 – via Internet Archive.

- Blencke-Dörr, Katharina (2007). "Wolfdietrich Schnurre". In Hockerts, Hans Günter (ed.). Neue deutsche Biographie [New German Biography] (in German). Vol. 23 (online ed.). Berlin. pp. 346–347. ISBN 978-3-428-00181-1. OCLC 486179.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Blume, Dorlis; Haunhorst, Regina; Zündel, Irmgard (19 January 2016). "Wolfdietrich Schnurre". Stiftung Haus der Geschichte der Bundesrepublik Deutschland (in German). Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- Boyken, Thomas; Immer, Nikolas (2020). Nachkriegslyrik. Poesie und Poetik zwischen 1945 und 1965 [Post-war poetry. Poesy and poetics between 1945 and 1965] (in German). Tübingen: Narr Francke Attempto Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8385-5402-0. OCLC 1226701696.

- Chisholm, David H. (1980). "Schnurre, Wolfdietrich (1920–)". In Bédé, Jean (ed.). Columbia dictionary of modern European literature. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-03717-4. OCLC 6421461. ProQuest 2137910064.

- Dittmann, Ulrich (3 May 2016). "Trümmerliteratur" [Rubble Literature]. Historisches Lexikon Bayerns (in German). Bavarian State Library. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- Hock, Sabine (20 October 2017). "Schnurre, Wolfdietrich". Frankfurter Personenlexikon (online edition) (in German). Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- Hüfner, Agnes (2012). "Schnurre, Wolfdietrich". In Kühlmann, Wilhelm (ed.). Killy Literaturlexikon. Autoren und Werke des deutschsprachigen Kulturraumes [Killy's Literature Encyclopaedia. Authors and Works of the German-Speaking Cultural Space] (in German). Vol. 10 (online ed.). De Gruyter. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- Hughes, Kenneth (1970). "Theory and Practice: Wolfdietrich Schnurre's Short Story Revisions". Studies in Short Fiction. 7 (2): 290–297. ISSN 0039-3789. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- Garland, Henry; Garland, Mary (1997). "Schnurre, Wolfdietrich". The Oxford Companion to German Literature. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-815896-7. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- Linder, Christian (9 June 2014). "Wolfdietrich Schnurre. Schlüsselfigur der frühen deutschen Nachkriegsliteratur" [Wolfdietrich Schnurre. A key figure in early German post-war literature]. Deutschlandfunk (in German). Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- Nusser, Peter (1966). "Wolfdietrich Schnurre's Short Stories". Studies in Short Fiction. 3 (2): 215–224. ISSN 0039-3789. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- Roberts, Ian (1 January 2005). "Perpetrators and Victims. Wolfdietrich Schnurre and the Bombenkrieg over Germany". Forum for Modern Language Studies. Oxford University Press (OUP). 41 (2): 200–212. doi:10.1093/fmls/cqi012. ISSN 1471-6860.

- Schult, Maike (15 September 2020). "Die Pflicht zur Deutlichkeit. Wolfdietrich Schnurre zum 100. Geburtstag" [The duty of clarity. On the occasion of Wolfdietrich Schnurre's 100th birthday]. Pastoraltheologie (in German). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. 109 (9): 436–442. doi:10.13109/path.2020.109.9.436. ISSN 0720-6259. S2CID 234674499.

- Schneider, Wolfgang (19 August 2010). "Wolfdietrich Schnurre: Der Schattenfotograf. Der geschundene, schuldbeladene, verfluchte Mensch" [Wolfdietrich Schnurre: The Shadow Photographer. The Maltreated, Guilt-ridden, Cursed Human Being]. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). ISSN 0174-4909. Retrieved 26 July 2021.

- Schnurre, Wolfdietrich (1960). "Das Begräbnis". Man sollte dagegen sein. Geschichten [One should be against it. Stories] (in German). Olten. pp. 21–28. ISBN 9780435387501. OCLC 186543831.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Schnurre, Wolfdietrich (1983). Dankrede [Acceptance Speech] (Speech). Georg Büchner Prize Ceremony (in German). Darmstadt.

- "Schnurre, Otto (1894–1979)". Kalliope-Verbund. Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz. 23 June 2016. Retrieved 22 April 2021.