The Wothlytype was an alternative photographic printing process, the eponymous 1864 invention of the German Jacob Wothly, in which a mixture of uranium ammonio-nitrate (uranyl nitrate) and silver nitrate in collodion formed a light-sensitive layer.

It was a short-lived positive printing process proposed to remedy the recognised impermanence of albumen paper, and compared to which, it was considerably more light-sensitive.[1][2]

Wothlytype printing-out-paper was superseded by collodio-chloride papers before the end of the 1860s.

Characteristics

The Wothlytype enabled positive prints to be made directly on paper. The photographic emulsion consisted of a special uranium collodion that replaced the iodide, the chlorine or silver bromide.[3] After exposure, the image was directly visible and was fixed immediately. Toning could be achieved in varying tones from deep blue-black to purple black. Sensitivity, efficiency and economy (reducing to degree the use of expensive silver) were advantages over competing processes. In addition, the collodion layer could also be transferred to ivory, wood, glass, porcelain and similar materials.

Procedure

First, the uranium collodion was applied to the paper, which was done with a brush, sponge or in a sensitizing bath, depending on the type of paper. After exposure, the images were immersed in an acidic bath for cleaning. The prints were washed to remove the acid, then immersed in a toning bath and then in a fixer. These two operations could also be combined. Finally, the images were washed a second time.

The British patent made public these details in the specification;

To one pound of plain collodion add from two to three ounces of nitrate of uranium and from 20 to 60 grains of nitrate of silver. The paper is prepared for printing by simply pouring the above sensitized collodion upon its surface, and hanging the sheets to dry in the dark. The printing is accomplished by exposing the paper to light under the negative in the usual manner, and for about the usual time required for silvered paper; print until the desired depth is reached. It is not necessary, as in the ordinary process, to print the positive to a greater intensity of color than the fixed picture is intended to have. After printing immerse the picture in a bath of acetic acid for about ten minutes, or until that portion of the salts not acted upon by the light has been dissolved. The picture is now fixed and finished by thorough washing or rubbing with a sponge or brush, or by rinsing in pure water; then dry. Changes in the tone of the picture to suit the taste may be made before drying, by using a bath of chloride of gold, or of hyposulphite of soda.[4]

Richard Kingham published further instructions for the amateur in 1865.[5]

History

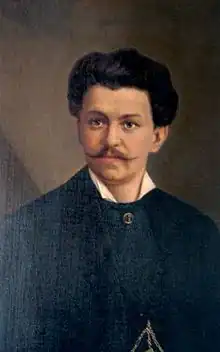

Wothly was a portrait photographer in business before 1853 and working in ambrotypes, whose studio was in Theaterplatz in Aachen. He went on in 1860 to make improvements to Woodward's solar camera.[6] Even before Wothly, numerous photographers had tried to use uranium salts in photography without lasting success. Wothly in 1864 introduced his new uranium platinum collodion process for positive paper images, in which he used platinum and palladium compounds to reduce the uranium salt. The Wothlytype was patented in Germany, America (15 August 1865),[7] Belgium (15 February 1865/No. 17147), England, France (24 September 1864),[8][9][10] Portugal[1] and Spain.

For France and Belgium, the Société française de Wothlytypie, founded specifically for this purpose by Emmanuel Mangel du Mesnil, took over licensing and distribution.[11]

The Photographic News of 7 October 1864 (in an article reproduced in The Times and Scientific American[12]) hailed it, and its novel use of collodion on paper, as a valuable improvement;

The new process which has been discovered in Germany by Herr Wothly, and from him has been named 'Wothlytype,' discards nitrate of silver, and discards albumen. For the former it uses a double salt of uranium, the name of which is at present kept secret; for the latter it uses collodion. We have explained that by the ordinary method, the paper to be printed is sized with albumen, and the surface of the albumen receives the silver preparation, which is sensitive to the light, and shows the printed image. The paper thus does not receive the image, but is, as it were, a mere bed on which lies the material that does receive it. By the substitution of collodion for albumen, a different result is reached. In the first place, the film of collodion on the paper yields a beautiful smooth surface on which to receive the image, and the result is, that pictures are printed upon it with wonderful delicacy. In the second place, the collodion, before it is washed upon the paper, is rendered sensitive by being combined with the salt of uranium. The sensitiveness, therefore, is not on the surface alone of the collodion film, it is in the film itself, and so completely passes through it, that even if it be peeled away from the paper, the image which it receives will be found on the paper beneath. The vehicle thus employed is not less superior to all others yet known for receiving the negative image on paper, than it is to all others yet known for receiving the negative image on glass. The metallic salt which combines with it has also rare merits. In the first place, the manipulations are very simple and easy – far more so than in the silver printing process, and thus the labour saved is considerable. Next, the paper, when rendered sensitive for printing, or 'sensitised,' as the photographers say, keeps pertectly for two or even three weeks, an immense boon to amateurs, who can thus have their stock of printing paper 'sensitised' for them; whereas, at present, when the paper receives the sensitive preparation, it has to be used almost immediately, and will not keep more than a day or two. Thirdly, the color and tone obtained are very various, including every shade that can be got by the ordinary silver plan; but, in addition, it has the advantage of being able to print any number of impressions of exactly the same color, and of doing away with all such difficulties as show themselves in mealiness and irregular toning. The precision of result is a great point. By the silver process, the results are never certain, and even when the print comes out perfect from the frame, the subsequent process of washing and fixing go seriously to alter it. Lastly, the permanent character of the new method is very remarkable. Nobody seems to know exactly why the old silver process gives way--whether it be on account of the albumen, or the nitrate of silver, or the hyposulphite of soda. We only know, that so many of the prints prepared by the old method fall away, that no reliance can be placed in those which seem to stand firm.[13]

Despite such claims, William Henry Fox Talbot in The British Journal of Photography shared his disappointment that "that the Wothlytype process produces an image consisting mainly of silver, for the first accounts of it were calculated to give a contrary impression. Nevertheless I believe it to be a valuable contribution to science." The Wothlytype proved also to suffer from fading.[2] John Werge recounted in 1890 how;

... the Wothlytype printing process was introduced to the notice of photographers and the public [in 1864]: first, by a blatant article in the Times, which was both inaccurate and misleading, for it stated that both nitrate of silver and hyposulphite of soda were dispensed within the process; secondly, by the issue of advertisements and prospectuses for the formation of a Limited Liability Company. I went to the Patent Office and examined the specification, and found that both nitrate of silver and hyposulphite of soda were essential to the practice of the process, and that there was no greater guarantee of permanency in the use of the Wothlytype than in ordinary silver printing.[14]

Demise

Wothlytype was considered dangerous and controversial.[15] Since Wothly suggested the use of the ingredients and spent years experimenting with improvements to his process, it is unclear whether Wothly's early death in 1873 at the age of 50 was due to his experiments with this radioactive element or, as previously suspected, to the loss of his fortune following the bankruptcy of his banker.

After Wothly's death the Wothlytype disappeared from the market.

Danger to health

Uranyl nitrate is an oxidizing and highly toxic compound. When ingested, it causes severe chronic kidney disease and acute tubular necrosis and is a lymphocyte mitogen. Target organs include the kidneys, liver, lungs and brain. It also represents a severe fire and explosion risk when heated or subjected to shock in contact with oxidizable substances. After uranium was recognized as the cause of the so-called photographer's disease (nephritis and gastritis), this element was hardly ever used in photography.

Literature

- Jacob Wothly, Mangel du Mesnil: Application de nouveaux procédés photographiques, Paris, Siege de la société, 1865, volume 1, p. 47.

External links

- Detailed description of the "Wothlytype" in Photographic Correspondence, 1865, online

- Wothly and the Wothlytype in "Photographic Archive", 1864.

References

- 1 2 Hannavy, John (2008). "Wothly, Jacob (active 1850s–1860s)". In Hannavy, John (ed.). Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography (1st ed.). New York: Routledge. pp. 1512–3. doi:10.4324/9780203941782. ISBN 978-0-203-94178-2.

- 1 2 Talbot, William Henry Fox. "Talbot Correspondence Project: TALBOT William Henry Fox to British Journal Of Photography". The Correspondence of William Henry Fox Talbot Project. Retrieved 2023-05-08.

- ↑ The Focal encyclopedia of photography digital imaging, theory and applications, history, and science. Michael R. Peres (4th ed.). Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier. 2007. pp. 120, 122. ISBN 978-1-136-10614-9. OCLC 1162213403.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ Wells, David A., ed. (1866). Annual of Scientific Discovery: Or, Year-Book of Facts in Science and Art for 1865. Exhibiting the Most Important Discoveries and Improvements in Mechanics, Useful Arts, Natural Philosophy, Chemistry, Astronomy, Geology, Zoology, Botany, Mineralogy, Meteorology, Geography, Antiquities, etc. Together with Notes on the Progress of Science during the year 1864, A List of Recent Scientific Publications: Obituaries Of Eminent Scientific Men, Etc (1866 ed.). Boston: Gould and Lincoln. pp. 186–7.

- ↑ Kingham, Richard, ed. (1865). The Amateur's Manual of Photography (2nd ed.). London: Richard Kingham. p. 85.

- ↑ Eder, Josef Maria (1945). History of Photography. Translated by Epstean, Edward. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. p. 392. ISBN 978-0-231-88370-2. OCLC 1104874591.

- ↑ American Patent.

- ↑ "CONTENU DU BREVET SELECTIONNE". 2008-11-12. Archived from the original on 2008-11-12. Retrieved 2023-05-08.

- ↑ Woodcroft, Bennet (1865). Alphabetical Index of Patentees and Applicants for Patents of Invention for the Year 1864. Printed and Published by Order at the Commissioners of Patents, Under the Act of 15 & 16 Victoriae, Cap. 83. Sec. XXXII. Holborn: Office Of The Commissioners Of Patents For Inventions. pp. 204, 208.

- ↑ Woodcroft, Bennet (1865). Chronological Index of Patents Applied for and Patents Granted for the Year 1864. Printed and Published by Order of the Commissioners of Patents, Under the Act of 15 & 16 VICTORIAE, Cap. 83. Sec. XXXII. Holborn: Office of the Commissioners of Patents for Inventions. p. 161.

- ↑ Wothly, Jacob; Mangel du Mesnil; Société Francaise de Wothlytypie (1865). Société Francaise de Wothlytypie : application de nouveaux procédes photographiques : M. Wothly, inventeur, M. , propriétaire des brevets pour la France et pour la Belgique. Nineteenth Century Collections Online (NCCO): Photography: The World through the Lens (eBook ed.). Paris: Siége de la Société. OCLC 936078944.

- ↑ "Improvement in Photography". Scientific American: A Weekly Journal of Practical Information in Art, Science, Mechanics, Chemistry and Manufactures. New York. XI (1): 308, 377. 2 July 1864.

- ↑ "A New Step in Photography". The Photographic News. VIII (318): 486–7. 7 October 1864.

- ↑ Werge, John (1890). The Evolution of Photography. With a Chronological Record of Discoveries, Inventions, Etc., Contributions To Photographic Literature, and Personal Reminiscences Extending Over Forty Years. Holborn: Piper & Carter and John Werge. OCLC 724896043.

- ↑ Harvie, David (2005). Deadly sunshine : the history and fatal legacy of radium. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Tempus. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-7524-3395-0. OCLC 57750137.