| Written on the Wind | |

|---|---|

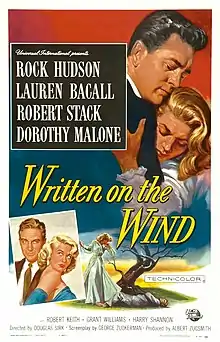

Theatrical release poster by Reynold Brown | |

| Directed by | Douglas Sirk |

| Screenplay by | George Zuckerman |

| Based on | Written on the Wind by Robert Wilder |

| Produced by | Albert Zugsmith |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Russell Metty |

| Edited by | Russell F. Schoengarth |

| Music by | Frank Skinner |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 99 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1.3 million[3] |

| Box office | $4.3 million (North America rentals)[4] |

Written on the Wind is a 1956 American Southern Gothic[5] melodrama film directed by Douglas Sirk and starring Rock Hudson, Lauren Bacall, Robert Stack, and Dorothy Malone. It follows the dysfunctional family members of a Texas oil dynasty, including the complicated relationships among its alcoholic heir; his wife, a former secretary for the family company; his childhood best friend; and his ruthless, self-destructive sister.

The screenplay by George Zuckerman was based on Robert Wilder's 1946 novel of the same title, a thinly disguised account (or roman à clef) of the real-life scandal involving torch singer Libby Holman and her husband, tobacco heir Zachary Smith Reynolds, who was killed under mysterious circumstances at his family estate in 1932. A film version of the novel was optioned by RKO Pictures and International Pictures in 1946, but the project was shelved because of threats from the Reynolds family. Universal Pictures acquired the rights to the novel after absorbing International Pictures, and began developing the film in 1955. Zuckerman made numerous alterations in his screenplay to avoid lawsuits from the Reynolds family, among them shifting the setting from North Carolina to Texas, and having the family fortune originate in oil rather than tobacco.

Filmed in Los Angeles in late 1955 and early 1956, Written on the Wind was released theatrically in England in the fall of 1956 before opening in the United States on Christmas Day 1956. The film broke opening-day box office records for Universal, and was a financial success. Malone won an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress,[6] Stack was nominated for Best Supporting Actor, and Victor Young and Sammy Cahn were nominated for Best Original Song.

Plot

Insecure, alcoholic playboy Kyle and his self-destructive sister Marylee are the children of Texas oil baron Jasper Hadley. Spoiled by their familial wealth and crippled by their personal demons, neither is able to sustain a personal relationship. Marylee has long been in love with Kyle's childhood friend Mitch Wayne, who is now a geologist for the Hadley Oil Company, but he sees her as a sister. She responds to his repeated rejections by pursuing brief physical relationships with various local men. Kyle continually seeks the approval of his father, who instead has long admired Mitch's humbleness and work ethic over that of his own children.

Kyle and Mitch take a business trip to New York City, where they meet Lucy Moore, an aloof secretary who works at the Hadley Company's Manhattan offices. While Lucy initially expresses interest in Mitch, it is Kyle who begins to court her. Lucy's cool demeanor fails to deter Kyle, and he invites her to accompany him on his private plane to Miami, which she accepts. After the trip, Kyle impulsively asks Lucy to marry him, and she agrees. The two return to Texas after a whirlwind honeymoon, and Lucy proves to be a stabilizing influence on his life throughout the first year of their marriage. Meanwhile, Marylee attempts to forge a romantic relationship with Mitch, whom she vows to marry, though Mitch secretly longs to be with Lucy.

Shortly after Kyle and Lucy's first wedding anniversary, Kyle learns from his doctor that he has a low sperm count and could be infertile. This news sends him into a deep depression, and he begins drinking heavily, at one point becoming severely intoxicated at the local country club and embarrassing Lucy. At the Hadley estate, Jasper confides in Mitch about his disappointment in his children, who he feels are reckless and irresponsible. Moments later, Marylee arrives at the house, escorted by police following a lovers' quarrel. That night, a defeated Jasper loses his grip on the railing and tumbles down the long front hall staircase. Mitch turns him over: He is dead. Jasper's death further destabilizes Kyle, and Lucy unsuccessfully attempts to help him overcome his self-loathing.

Mitch informs Lucy that he plans to quit his job at the Hadley Oil Company and relocate to Iran. Mitch drives Lucy to a doctor's appointment, where she learns that she is pregnant; the doctor also informs her about his prior diagnosis of Kyle's infertility. That night, during a dinner with Mitch and Marylee, Lucy reveals her pregnancy to Kyle. Assuming Mitch is the father and that he and Lucy are having an affair, Kyle enters a drunken rage and assaults Lucy, but is stopped by Mitch, who forces him out of the house. The attack results in Lucy suffering a miscarriage that night. Meanwhile, an emasculated, inebriated Kyle visits the local tavern before returning to the house brandishing a pistol, intent on murdering Mitch. Marylee attempts to stop him, and, during the struggle over the gun, the weapon discharges, killing Kyle.

Resentful of Mitch's love for Lucy, Marylee attempts to coerce Mitch into marrying her by threatening to tell police he murdered Kyle. Mitch denies her, and, at the inquest, she first testifies that Mitch shot Kyle, but then tearfully changes her story and describes events as they really occurred, since she still cared about Mitch. Mitch and Lucy leave the Hadley home together. Marylee is left to mourn the death of her brother and father and to run the company alone, as Mitch leaves and goes to Iran.

Cast

- Rock Hudson as Mitch Wayne

- Lauren Bacall as Lucy Moore Hadley

- Robert Stack as Kyle Hadley

- Dorothy Malone as Marylee Hadley

- Robert Keith as Jasper Hadley

- Grant Williams as Biff Miley

- Robert J. Wilke as Dan Willis

- Edward Platt as Dr. Paul Cochrane

- Harry Shannon as Hoak Wayne

- John Larch as Roy Carter

- Joseph Granby as Judge R.J. Courtney

- Roy Glenn as Sam

- Maidie Norman as Bertha

- William Schallert as Reporter Jack Williams

- Joanne Jordan as brunette

- Dani Crayne as blonde

- Dorothy Porter as secretary

Production

Development

The film's source novel by Robert Wilder was inspired by the life and death of Zachary Smith Reynolds, son of R. J. Reynolds and heir to the Reynolds Tobacco fortune, who died from a gunshot wound to the head at his family's estate after a birthday party.[7] His wife, torch singer Libby Holman, and close friend Alber Walker, fell under suspicion due to conflicting accounts given about the night's events, though neither were ever formally charged with a crime.[7]

The novel had been optioned for a feature film adaptation by RKO Pictures in 1945 before the rights were sold to International Pictures the following year after RKO shelved the project.[7] In 1946, Universal Pictures acquired the rights to the novel after absorbing International Pictures; however, the project remained in limbo due to pressure from the Reynolds family, who threatened to launch a lawsuit against any film version of Wilder's novel.[7]

In 1955, producer Albert Zugsmith, convinced the project could be a huge success for the studio, hired George Zuckerman to adapt a screenplay, though a number of notable changes were necessitated to avoid a lawsuit from the Reynolds family: several characters were eliminated or had their ages changed; the Hadley family fortune, which in the novel had been acquired from tobacco, was instead from oil; and its setting changed from North Carolina to Texas.[8] Several drafts of the screenplay were submitted to the Motion Picture Production Code before it was passed in late 1955.[9]

Casting

Lauren Bacall, whose film career was foundering in the mid-1950s, accepted the relatively unflashy role of Lucy Moore at the behest of her husband, Humphrey Bogart. At the same time she was shooting the film, she was preparing for a television adaptation of Noël Coward's Blithe Spirit, co-starring Coward and Claudette Colbert.

Dorothy Malone, a brunette previously best known as the brainy bespectacled bookstore clerk in a scene with Humphrey Bogart in The Big Sleep (1946), had more recently played small supporting roles in a long string of B movies. For this film, she dyed her hair platinum blonde to shed her "nice girl" image and portray the obsessive Marylee Hadley. Her Oscar-winning performance finally gave her cachet in the film industry.

Robert Stack felt the primary reason he lost the Oscar to Anthony Quinn (whose winning performance in Lust for Life was no more than 25 minutes long) was that 20th Century Fox, which had lent him to Universal-International, organized block voting against him to prevent one of its contract players from winning an acting award while working at another studio.[10]

This was the sixth of eight films Douglas Sirk made with Rock Hudson, and the most successful. The next year, Sirk reunited key cast members Hudson, Stack, and Malone for The Tarnished Angels, a film about early aviators based on William Faulkner's novel Pylon.

Filming

Principal photography began on November 28, 1955, in Los Angeles on the Universal Studios lot.[11] The sequence set at Manhattan's 21 Club was reconstructed on the Universal lot using photographs and dressed with actual paraphernalia from the restaurant, such as napkins and other items lent by the club owners.[1] The staircase set featured in the film as the Hadleys' home had also been used in Universal's 1925 film version of The Phantom of the Opera, as well as the 1936 film My Man Godfrey.[1]

Written on the Wind was one of the very few "flat wide screen" titles to be printed "direct to matrix" by Technicolor. This specially ordered 35-mm printing process was intended to maintain the highest possible print quality, as well as to protect the negative. Another film that was also given this treatment was This Island Earth, which was also a Universal-International film.

Music

The title song, written by Sammy Cahn and Victor Young, was sung by the Four Aces during the opening credits. The film's score was composed by Frank Skinner.

Release

Box office

Written on the Wind was released theatrically in London on October 5, 1956.[2] It was subsequently released on Christmas Day 1956 in several U.S. cities, including Los Angeles, New Orleans, Chicago, and Tulsa, before having its New York City premiere on January 11, 1957.[1]

The film broke records for having the highest single-day gross of any Universal Pictures film, including at New Orleans's Joy Theatre, where it had box office receipts totaling $3,036 (equivalent to $32,679 in 2022) on its Christmas Day opening.[12] It went on to earn rentals (box-office receipts returned to the producer) of $4.3 million (equivalent to $46,284,211 in 2022) in North America alone.[4]

Home media

The Criterion Collection released Written on the Wind on DVD on June 29, 2001.[13] Criterion released a remastered 2K Blu-ray edition of the film on February 1, 2022.[14]

Interpretations

Since its premiere, Written on the Wind has been analyzed and interpreted by professional critics and theorists, amateur writers, and melodrama fans. The film explores themes of love, betrayal, and social status. Here are a few interpretations of the film:

Social Commentary

In terms of its social criticism, the picture is best understood as a parody of the ultimate achievement of the American dream. The Hadleys have achieved the American ideal of material affluence, but they are unhappy and isolated. Their acceptance of materialism's ideology makes it impossible to question its foundations.[15] The Hadleys rule their town, and the film's opening scenes show endless rows of phallic oil towers and the massive corporate skyscraper; the Hadleys are everywhere, but emotionally and spiritually they are nowhere. One of the film's central topics is the impact of 1950s materialism on the American character.

Exploration of Love and Desire

The film can be interpreted through the complexity of love and desire between the main characters. It suggests that desire can lead people to make irrational choices. Lucy is torn between her husband and her growing attraction to Mitch Wayne.[16] Similarly, Mitch struggles with his loyalty to his best friend, Kyle, and his feelings for Lucy. Kyle Hadley's obsession with his best friend's wife, Lucy, leads him to neglect his own wife. These conflicting obligations drive a lot of tension and create a painful process.[16] The film suggests that navigating emotions can have positive and negative consequences. The men and women of Written on the Wind are racked with guilt and tangled in increasingly indistinct relationships.[16]

Reception and legacy

.jpg.webp)

Alan Brien, reviewing the film for the Evening Standard following its British release in October 1956, commented on its glossy appearance, writing: "All of the characters in Written on the Wind talk like, act like, and even look like the characters in a woman's magazine serial. The men have the same improbably over-bronzed, regular faces, and wear the same outsized draped suits so dear to the heart of fiction illustrators."[2]

In his review in The New York Times upon the initial release of the film, Bosley Crowther said: "The trouble with this romantic picture ... is that nothing really happens, the complications within the characters are never clear and the sloppy, self-pitying fellow at the center of the whole thing is a bore."[17]

Variety praised the "outspoken drama" and said: "Intelligent use of the flashback technique ... builds immediate interest and expectancy without diminishing plot punch. Tiptop scripting ... dramatically deft direction ... and sock performances by the cast add a zing to the characters that pays off in audience interest. Hudson scores ... [Stack], in one of his best performances, draws a compelling portrait of a psychotic man ruined by wealth and character weaknesses.... Malone hits a career high as the completely immoral sister."[18]

On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, 87% of 31 reviews are positive, and the average rating is 7.7/10.[19] On Metacritic — which assigns a weighted mean score — the film has a score of 86 out of 100 based on 15 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[20]

In 1998, Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times called the film "a perverse and wickedly funny melodrama in which you can find the seeds of Dallas, Dynasty, and all the other primetime soaps. Sirk is the one who established their tone, in which shocking behavior is treated with passionate solemnity, while parody burbles beneath.... To appreciate a film like Written on the Wind probably takes more sophistication than to understand one of Ingmar Bergman's masterpieces, because Bergman's themes are visible and underlined, while with Sirk, the style conceals the message. His interiors are wildly over the top, and his exteriors are phony—he wants you to notice the artifice, to see that he's not using realism but an exaggerated Hollywood studio style.... Films like this are both above and below middle-brow taste. If you only see the surface, it's trashy soap opera. If you can see the style, the absurdity, the exaggeration, and the satirical humor, it's subversive of all the 1950s dramas that handled such material solemnly. William Inge and Tennessee Williams were taken with great seriousness during the decade, but Sirk kids their Freudian hysteria."[21]

TV Guide described the film as "the ultimate in lush melodrama", "Douglas Sirk's finest directorial effort", and "one of the most notable critiques of the American family ever made."[22]

Leonard Maltin gave the film three out of four stars, calling it "Irresistible kitsch."[23]

The New Yorker's Richard Brody discusses the film, which he says may be "Sirk's most full-blossomed achievement", in a video posted on the magazine's website in 2015.[24]

In 2005, actress Lauren Bacall accepted the Frontier Award on behalf of the film from the Austin Film Society, which annually makes inductions into the Texas Film Hall of Fame recognizing actors, directors, screenwriters, filmmakers, and films from, influenced by, or inspired by the Lone Star State.[25]

Accolades

| Award | Category | Nominee(s) | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards | Best Supporting Actor | Robert Stack | Nominated | [26] |

| Best Supporting Actress | Dorothy Malone | Won | ||

| Best Song | "Written on the Wind" Music by Victor Young; Lyrics by Sammy Cahn |

Nominated | ||

| Golden Globe Awards | Best Supporting Actress – Motion Picture | Dorothy Malone | Nominated | [27] |

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Written on the Wind". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved February 6, 2022.

- 1 2 3 Brien, Alan (October 4, 1956). "Poverty and Bliss for Miss Bacall". Evening Standard. p. 6 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Reversing Poor Broadway Showing". Variety. April 3, 1957. p. 7.

- 1 2 Cohn, Lawrence (October 15, 1990). "All-Time Film Rental Champs". Variety. p. M196.

- ↑ Wigley, Samuel (July 10, 2017). "10 great southern gothic films". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on December 10, 2021.

- ↑ Dorothy Malone Wins Supporting Actress: 1957 Oscars

- 1 2 3 4 Evans 2013, p. 14.

- ↑ Evans 2013, pp. 14–16.

- ↑ Evans 2013, pp. 16–17.

- ↑ "Written on the Wind (1957) – Articles". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ↑ Evans 2013, p. 21.

- ↑ Evans 2013, p. 13.

- ↑ Duncan, Phillip (July 6, 2001). "Written on the Wind". DVD Talk. Archived from the original on August 13, 2020.

- ↑ "Written on the Wind – Criterion Collection". High-Def Digest. Archived from the original on January 31, 2022.

- ↑ "Written on the Wind". www.lotsofessays.com. Archived from the original on May 10, 2023. Retrieved June 3, 2023.

- 1 2 3 McClendon, Blair (February 1, 2022). "Written on the Wind: No Good End". www.criterion.com. The Criterion Collection. Archived from the original on May 10, 2023. Retrieved June 3, 2023.

- ↑ Crowther, Bosley. "Movie Review : Screen: Sad Psychosis; 'Written on the Wind' Opens at Capitol". The New York Times. Retrieved September 22, 2017.

- ↑ "Written on the Wind". Variety. December 25, 1956. Archived from the original on March 17, 2016.

- ↑ "Written on the Wind". Metacritic. Fandom, Inc. Retrieved December 1, 2022.

- ↑ "Written on the Wind Reviews". Metacritic. Fandom, Inc. Retrieved December 1, 2022.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger. "Written on the Wind Movie Review (1956)". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved April 29, 2022 – via RogerEbert.com.

- ↑ "Written On The Wind". TV Guide. Archived from the original on April 2, 2019.

- ↑ "Written on the Wind (1957) – Overview". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ↑ Brody, Richard (December 17, 2015). "Movie of the Week: "Written on the Wind"". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on July 31, 2021.

- ↑ Texas Film Hall of Fame|Austin Film Society

- ↑ "The 29th Academy Awards (1957) Nominees and Winners". Oscars.org (Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences). Retrieved August 21, 2011.

- ↑ "Written on the Wind – Golden Globes". HFPA. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

Bibliography

- Evans, Peter William (2013). Written on the Wind. BFI Film Classics. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-844-57866-5.[1]

External links

- Written on the Wind at IMDb

- Written on the Wind at AllMovie

- Written on the Wind at Rotten Tomatoes

- Written on the Wind at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Written on the Wind at the TCM Movie Database

- Essay by Laura Mulvey at The Criterion Collection

- Richard Brody's take on Written on the Wind

- ↑ "Written on the Wind". www.lotsofessays.com. Archived from the original on May 10, 2023. Retrieved June 3, 2023.