| Yang Xi | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Seal script for Yang Xi | |||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 楊羲 | ||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 杨羲 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||

| Hangul | 양희 | ||||||||||||

| Hanja | 楊羲 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||

| Kanji | 楊羲 | ||||||||||||

| Hiragana | ようぎ | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Yang Xi (楊羲, 330-c. 386), courtesy name Xihe (羲和, a mythological solar deity), was an Eastern Jin dynasty scholar, calligrapher, and mystic, who is best known for the "Shangqing revelations" that were purportedly dictated to him by Taoist deities between 364 and 370. The Taoist polymath Tao Hongjing subsequently compiled and redacted Yang's revealed texts into the c. 499 Zhen'gao (真誥, Declarations of the Perfected) compendium, which formed the foundations of the Shangqing School of Taoism.

Life

The life of Yang Xi was closely intertwined with the aristocratic Xu (許) family in Jurong, Jiangsu. He was employed as the in-house medium/shaman and spiritual advisor when the Perfected Ones directed Yang to transmit the revelation manuscripts to Xu Mi (許謐), an official in the court of Emperor Ai of Jin, and his son Xu Hui (許翽). The sinologist Isabelle Robinet stresses that Yang Xi was a mystic or a visionary, as opposed to a medium. Contrasting a simple medium who supposedly conveys information from a god or spirit, Yang Xi produced a comprehensive religious system with sacred scriptures, philosophy, and practices. Furthermore, he was highly cultured, a superb calligrapher, and well-informed about the Chinese classics and Buddhist scriptures available in the 4th century[1]

Few historical facts are known about Yang Xi's life, and most information comes from his own revealed texts. The Zhen'gao, for instance, is the only early record of Yang's birth and death dates; it says that when he was betrothed to the heavenly Consort An in 365, he told her that he had been born in October of 330 and was 36.[2] The actual date of his death is unknown; Tao Hongjing accepts the revelatory prediction that Yang would ascend to the heavens "in broad daylight" in 386, thus avoiding death in the forthcoming end of the world in 392,[3] Yang had an early connection with Daoism in 350 when Wei Huacun's eldest son, Liu Pu (劉璞) gave Yang a manuscript of the Lingbao School Wufu xu (五符序, Prolegomena to the Five Talismans of the Numinous Treasure).[4] Although Tao had copies of the Xu's jiapu (家譜, Family Genealogy), he preferred to rely upon the prophetic contents of the revelations themselves; the family records said Xu Mi died in 373, but Tao said 376 when it was predicted that he would enter Shangqing heaven.[5]

Unlike Yang's life, we have detailed information about the Xu family in more reliable sources such as the Book of Jin official dynastic history. The Xus had been established in Jurong since 185 CE, when Xu Guang (許光) joined the southward migration during the decline of the Eastern Han dynasty.[6] From 317 to 420, Jurong was the Eastern Jin capital Jiankang (modern Nanjing), where many Xu family members served as government officials.

The head of the household, Xu Mai (許邁, 300-348), whose father Xu Fu (許副) had converted to the Way of the Celestial Masters, resigned from his official career and turned to practicing Daoist waidan "external alchemy", meditation, and daoyin exercises.[7] He was a disciple of Bao Jing (260-330), the teacher and father-in-law of Ge Hong, and of the Xu family Way of the Celestial Masters jijiu (祭酒, Libationer) Li Dong (李東). In 346, Xu Mai changed his name to Xu Xuan (許玄), travelled to sacred mountains, and was said to have become a xian "transcendent; immortal" and disappeared.[4] The uncertain location is given as Chishan (赤山) in Rongcheng, Shandong or Xishan (西山) in Lin'an, Zhejiang.[8]

Yang Xi told Xu Mai's younger brother, Xu Mi (許谧, 303-376), the Perfected Ones said the Xu family would have an important role in the revelations. He became Yang's patron and help transmit the prophetic texts. In 367, Yang informed Xu Mi about Mao Ying's prophesy that in nine years he would be transferred from the earthly bureaucracy to begin his honorary position in the Shangqing Heaven.[9] Despite repeated celestial admonitions, Xu completed his official career in the capital as Senior Officer to the Defensive Army. He subsequently moved to Maoshan (茅山) or Mount Mao, about 15 miles southeast of the family home in Jurong, where he had erected a wooden jìngshì (靜室, Quiet Chamber) that served as his oratory for meditation and worship.[10]

Xu Mi's third son, Xu Hui (許翽, 341-c. 370), on the other hand, resigned from his official position as Assistant for Submission of Accounts, returned his wife to her family, and retired his father's retreat on Mount Mao in 362. An excellent calligrapher, he became close friends with Yang Xi, and devoted himself to the study and practice of the revealed scriptures.[11] In 370, Yang had a prophetic dream with an "untimely summons" that guaranteed Xu Hui a privileged official position awaiting him in the World Beyond.[12] Soon afterwards, he apparently drank a poisonous alchemical elixir to commit "ritual suicide" as a means of joining the ranks of the immortals in Shangqing Heaven.[13]

After Xu Mi's wife died in 362, the Xu family hired the medium Yang Xi to establish contact with her spirit. She explained the basic organization of heaven, and introduced Yang to other spirit figures.[14][15] Xu Mi introduced Yang Xi to the Prince of Langye (琅琊) Sima Yu (司馬昱, 320-372, later Emperor Jianwen of Jin), who employed him as both Household Secretary and Minister of Instruction.[16]

Between 364 and 370, Yang Xi had a series of midnight visions in which zhenren "Perfected Ones" from the Heaven of Shangqing Supreme Purity appeared to him in order to communicate both their sacred texts and personal instructions. The Daoist term zhenren has many English translations such as "Real Person", "Authentic Person", "True Person", "Perfected Person", and "Perfected".[17] The visions were dictated to Yang alone, but he was directed to transcribe them for transmission to Xu Mi and Xu Hui, who would make additional copies. The revelations included jing (經, Scriptures), several zhuan (傳, Hagiographies) of the Perfected, and supplementary jue (訣, Instructions) about understanding and employing the texts. Early readers of these revealed texts were impressed both by the erudite literary style of ecstatic verse and the artistic calligraphy of Yang Xi and Xu Hui.[18] The dated texts of the original Mao Shan records come to an end in 370, after which there is no more historical evidence of the principals.[19]

When the elder Xu died in 376, the younger Xu's son Xu Huangmin (許黄民, 361-429) spent several years compiling all the Yang-Xu transcribed scriptures, talismans, and secret registers. He subsequently distributed copies among his friends and relatives.[5]

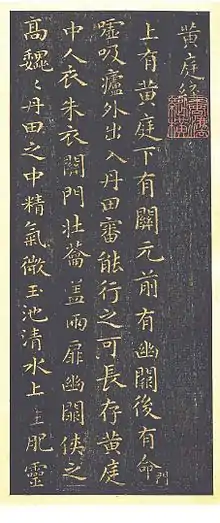

Although no autograph copies of Yang Xi's famous calligraphy have survived, one well-documented stone rubbing version of the revealed Huangting jing (黃庭經, Yellow Court Scripture) has been given special attention. The Song dynasty connoisseur and critic Mi Fu (1051-1107) analyzed four manuscripts of the Huangting jing, and said the best one was written on a silk scroll with a provenance that he traced back to the early 8th century. Mi disagreed with a former owner Tao Gu (陶穀, 903-970) who said that Wang Xizhi wrote the manuscript, and concluded it was a superb example of calligraphy from the Six Dynasties period. The Ming dynasty calligrapher and painter Dong Qichang (1555-1636) was so impressed by the Mi Fu manuscript that he made a copy, recommend it as the best model for studying kaishu script, and included it as the first example in his classic Xihong tang fatie (戲鴻堂法帖, Calligraphy Compendium of the Hall of the Playful Goose). Dong's colophon attributed the calligraphy to Yang Xi himself and described it as "the traces of a holy immortal". Ledderose calls Dong's attribution to Yang "extremely optimistic".[20]

Shangqing revelations

According to Shangqing School tradition, the fundamental Maoshan or Shangqing revelations were dictated by a group of some two dozen Taoist zhenren Perfected from the Heaven of Shangqing Upper Clarity. They were first revealed in 288 to Lady Wei Huacun, a Way of the Celestial Masters adept proficient in Taoist meditation techniques; and then to Yang Xi from 364 to 370. Tao Hongjing compiled and redacted these transcribed revelation texts from 490 to 499, constituting the Shangqing scriptures that formed the basis of the school’s beliefs in new visualization- and meditation-based ways to reach immortality. "The world of meditation in this tradition is incomparably rich and colorful, with gods, immortals, body energies, and cosmic sprouts vying for the adept's attention.".[21]

Yang wrote down the content of every vision in ecstatic verse, recording the date along with the name and description of each Perfected. The purpose of the revelations was to set up a new syncretic faith that claimed to be superior to all earlier Taoist traditions.[4]

The Zhen'gao records that Yang Xi's visitations started in the 11th month of 359 and continued at a rate of about six times a month up to 370. The heavenly maidens who would visit Yang Xi at night "never write themselves, neither with their hands nor with their feet", but instead would take his hand and engage him in a "sublime relationship" while he transcribed the sacred texts.[22]

The Perfected who appeared to Yang Xi constituted three groups.[23] The first were early sages in the Shangqing movement. The three brothers Mao Ying (茅盈), Mao Gu (茅固), and Mao Zhong (茅衷), referred to as the Three Lords Mao (三茅真君), supposedly lived in the 2nd century BCE. Wei Huacun herself was among the Perfected, and she became Yang's xuanshi (玄師, Teacher in the Invisible World).[16] Another notable example is the legendary xian transcendent Zhou Yishan (周義山, b. 80 BCE). The second group includes Yang Xi's bride, the Perfected Consort An (安妃) and her mythological parents Master Redpine and Lady Li (李夫人). The third are the Queen Mother of the West's daughters, such as the Lady of Purple Tenuity (紫微夫人) who served as matchmaker between Yang Xi and Consort An.

Some texts the Perfected bestowed upon Yang were modified or corrected versions of existing texts. For example, a new version of the Huangting jing (黃庭經, Yellow Court Scripture) was a corrected replacement of the text by the same name that was given to Wei Huacun along with thirty other revealed texts. Yang's new version of the Huangting jing was called the Neijing jing (内景經, Book of the Inner Effulgences) in contrast to the older version called the Waijing jing (外景經, Book of the Outer Effulgences).[24] The Perfected also dictated to Yang a more Taoistic version of the Sutra of Forty-two Chapters, believed to have been the first Buddhist scripture translated into Chinese.[25]

The Dadong zhenjing (大洞真經, Scripture of the Great Cavern) was also dictated to Yang. Although earlier fragments exist, the oldest extant complete text, known as the Shangqing dadong zhenjing (Perfected Scripture of the Great Cavern of Highest Clarity, 上清大洞真經), was edited by the twenty-third patriarch of the Shangqing School, Zhu Ziying (朱自英, 974–1029), and collated in the 13th century by the thirty-eighth patriarch, Jiang Zongying (蔣宗瑛, d. 1281).[26]

While most Shangqing revelations were addressed to Yang Xi and the Xu family, some were specifically for transmission to their relatives and friends. Prognostications for family members covered personal matters such as health, sickness, and longevity. Other materials included several messages and poems for the important official Qie Yin (郄愔, 313-384), and political predictions for acting regent Sima Yu (above).[27]

The central apocalyptic message transmitted by Yang to the Xus was that they were among a chosen few people destined to survive the imminent destruction of the world, and to live on as members of the Perfected ruling hierarchy in the new age. The three progenitors of the Shangqing sect shared with other contemporary sects a belief in an imminent apocalypse, which was originally prophesied to begin in 392, when the messianic Housheng daojun (後聖道君. Perfect Lord, Sage Who Is to Come, identified as Li Hong) would descend to earth.[28] After that failed to occur, Tao recalculated the devastation would come in 507, and in 512 the messiah would descend to gather up the elect survivors.[29]

Scholars have dismissively described the contents of the Shangqing revelations as "syncretistic", based chiefly upon a superficial reading of the Zhen'gao. Much of the content in Yang's visions seems to derive from a variety of older sources, Taoist, Buddhist, scholarly, and popular, despite the "resplendent homogeneity which originally disparate elements appear to have acquired in his inspired transcriptions".[30]

Tao Hongjing

The Daoist scholar, pharmacologist, and alchemist Tao Hongjing (456-536) was the redactor-editor of the basic Shangqing revelations and a founder of the Shangqing School.[31] Most of what is known about Yang Xi derives from Tao's scholarly and detailed writings.

In 483, Tao became fascinated with the Shangqing revelations given to Yang Xi more than a century earlier. Tao's Daoist master Sun Youyue (孫遊岳, 399–489)—who had been a disciple of Lu Xiujing (陸修靜, 406–477), the standardizer of the Lingbao School rituals and scriptures—showed him some fragments of Yang Xi's and Xu Hui's original textual manuscripts.[32][33] Tao Hongjing was enthralled by their calligraphy, and later wrote, "In my view, it is not something that could have been achieved by skill alone. Rather, Heaven conferred on them this mastery, that it might lead others to enlightenment". Tao decided to undertake the task of recovering all that remained of the original autograph manuscripts by Yang, Xu Mai, and Xu Mi.[34] Comparing the manuscripts of Yang and the two Xus, Tao Hongjing said, "the calligraphy of Master Yang is the most accomplished … The reason that his fame did not spread is only that his social position was low and that, moreover, he was suppressed by the Two Wangs", that is, his famous calligraphic contemporaries Wang Xizhi and Wang Xianzhi.[35]

Using calligraphy as his primary criterion of authenticity, Tao Hongjing assembled a substantial corpus of autograph texts by Yang and the Xus, as well as a number of transcripts written by others concerning the same Shangqing revelations.[36] These included flawed or forged copies, and "many fakes" had already been produced among the select circles that knew of the Shangqing revelations.[37] In Tao's estimation, "Of all the manuscripts in the handwriting of these three gentlemen extant at the present time, there are over ten [juan 卷 "scrolls; volumes" of] individual scriptures and biographies of greater or lesser length, mainly transcripts made by the younger [Xu], and more than forty scrollfuls [卷] of oral instructions dictated by the Perfected, the larger part of which are in Yang's hand."[38]

Tao knew two kinds of manuscripts transcribed by Yang, those written in regular script and those in cursive script. First, he wrote the original versions of revealed scriptures and hagiographies in the sanyuan bahui (三元八會, three origins and eight connections) script that was only used by celestial beings and not readily intelligible to mortals, other than Yang. Second, he wrote down the oral instructions dictated by the Perfected in a quick caoshu cursive script or xingshu semi-cursive script. All the Yang's writing done when receiving the revelations is hurried and abbreviated. Only later, when he had emerged from his trance, he would remember the words, make revisions, and transcribe the drafts into carefully written "new lishu" neo-clerical script, which is now called kaishu regular script.[39]

Tao Hongjing retired to Maoshan in 492 and spent seven years editing and annotating the manuscripts, based upon the notes of Yang Xi and his patrons Xu Mai and Xu Mi. His enterprise resulted in two major works, the c. 499 Zhen'gao (真誥, Declarations of the Perfected) that was intended for wide circulation, and the esoteric c. 493-514 Dengzhen yinjue (登真隱訣, Concealed Instructions for the Ascent to Perfection) that provides Shangqing adepts with guidance for their practices.[40] The Zhen'gao textual collection is divided into seven books. The first five mainly contain the revelations from the Perfected, the sixth includes letters and notes written by Yang and the Xus themselves, along with Tao's detailed commentary for these texts. The seventh book is Tao's editorial postface, comprising a genealogy of the Xu family and a historical account of the Yang-Xu manuscripts. The Dengzhen yinjue comprises technical materials from the Scriptures and Hagiographies of the Perfected, as well as from revealed texts included in the Zhen'gao. Only three of the original twenty-four chapters are extant, and they describe meditation practices, apotropaic techniques, and rituals.[30] In addition, Tao composed a commentary to Yang Xi's Jianjing (劍經, Scripture of the Sword) revelation, which is included in the 983 Taiping Yulan encyclopedia.[41]

Tao Hongjing's "Account of the Diffusion of the Yang-Xu Manuscript Corpus" (Zhen'gao 7) records a remarkable case of unauthorized copying, "amounting to a rabid, if idealistic, kleptomania".[42] In 404, following the violent "Daoist" rebellion of Sun En, Xu Mi's son Xu Huangmin (above) moved to the Shan (剡) region in eastern Zhejiang, taking with him the bulk of the original Shangqing revealed manuscripts. Xu gave the hereditary texts to his hosts, Ma Lang 馬郎 and Du Daoju 杜道鞠, for safekeeping. However, they were Way of the Celestial Masters practitioners who only kept the scriptures, without knowing the proper way to practice them.[43] The story involves a talented scholar named Wang Lingqi 王靈期 who was envious of the great influence and wealth that Ge Chaofu attained from producing the Lingbao School Scriptures, and wanted to spread the Shangqing revelations to the public. Wang requested Xu Huangmin to give him the texts but was refused. Following the traditional test of a disciple's sincerity, Wang then "stayed out in the frost and snow until it nearly cost him his life", whereupon Xu, who was moved by the extent of his devotion, allowed Wang to copy the revelations. Tao writes that

Having obtained the Scriptures, Wang returned home leaping for joy. Yet after due consideration he realized that it would not do to publish abroad their most excellent doctrine 至法, and that (the form of) their cogent sayings 要言 would not lend itself to wide diffusion. Therefore he presumed to make additions and deletions, and embellished the style. Taking the titles (of scriptures) in the Lives of (Lord) Wang and (the Lady) Wei as his basis, he began to fabricate works by way of furnishing out those listings. On top of that, he increased the fees for transmission, in order that his [Dao] might be more worthy of respect. There were in all more than fifty such works. When the eager and ambitious learned of this great wealth of material, they came one after another to do him honor and receive them. Once transmission and transcription had become widespread, the branch and its leaves were commingled. New and old were mixed indiscriminately, so that telling them apart is no easy task. Unless one has already seen the Scriptures of the Perfected, it is really difficult to judge with certainty.[44]

This description of Wang Lingqi deviously increasing the "fees for transmission" refers to the Shangqing tradition that none of Yang Xi's revealed texts could be transmitted without the recipient swearing an oath of secrecy and paying predetermined quantities of precious metal and silk.[45] In a sense, each of Yang's and Wang's texts "bore their own price-tag".[46] For examples, compare one of Yang's revealed texts with one of Wang's imitations. Yang Xi's authentic 364 or 365 Basu zhenjing (八素真經, True Classic of the Eight Purities) contains two rituals for absorbing beneficial qi from the Five Planets. In order to receive the first one, the disciple must give the transmitting master forty feet of fine white silk and two silver rings; and for the second ritual, he is to furnish thirty-two feet of blue silk, "as an earnest that he will not disclose it, till the end of his life, till all the blood be gone from his body".[45] Wang Lingqi's fake Taishang shenhu yujing (太上神虎玉經, Jade Scripture of the Most High Concerning the Spirit Tiger) lists the fees for copying as, "ten ounces of the finest gold: as a pledge to the spirits, ninety feet of brocaded silk: to enter into a contract with the Nine Heavens, and thirty feet of blue silk: to bind his heart by oath".[47]

In Shangqing traditional beliefs, any disciple who received a revealed document through authorized transmission had entered into "a bonded contract with the powers on high", and invested in "a sort of celestial security". After death, the disciple would enter into the Unseen World bearing documentary proof that certified the purchase of a posthumous official rank among the Perfected.[48] Moreover, the simple act of textual transmission made of each recipient a potential master, according to the classical formula that "He who transmits a scripture becomes a Teacher". This created an extended community of Shangqing Daoists bound to one another in overlapping master-disciple relationships through oaths that supported the transmission of sacred texts, "possession of which conferred both identity and authority".[49]

Lothar Ledderose explains the unique problems of "authenticity" in the transmission of the Maoshan manuscripts.

Authenticity was not simply a question of fact (as one normally regards it in the West), but rather a matter of degree. The mystic Yang Hsi immediately copied his own handwriting when he awoke from his trance, and these copies in turn were copied by the two Hsus. But even Yang's trance writings, in a sense, may be called copies, copies of otherworldly texts that existed on a primordial level. As such they were not legible by ordinary mortals and therefore had to be transcribed by Yang into a script of this world. Thus there exists no one unique handwritten piece in contrast to which all the other versions would be copies or forgeries. Rather there is a chain of copies whose beginnings are hidden in obscurity. What matters is not so much the authenticity of a single scroll but the authenticity of the chain of copies.[50]

Stoner seer

Yang Xi was a regular user of marijuana, according to Joseph Needham and his Science and Civilisation in China collaborators, Ho Ping-Yü, Lu Gwei-Djen, and Nathan Sivin. They conclude that he was "aided almost certainly by cannabis" in writing the Shangqing revelations.[51]

Yang Xi's revealed Maojun zhuan (茅君傳, Life of Lord Mao) text says that an immortality elixir, the 24-ingredient sirui dan (四蕊丹, Fourfold Floreate Elixir), which includes the 14 ingredients in langgan huadan (琅玕華丹, Elixir Efflorescence of Langgan) can be regularly taken in a mixture of hemp juice, producing hallucinatory sensations. "A daily dosage allowed one to divide his body and become ten thousand men, and to ride through the air". Tao Hongjing records seeing a copy of the hemp-juice potion formula in Hsu Mi's handwriting.[52]

The hallucinogenic properties of cannabis were common knowledge in Chinese medical and Daoist circles for two millennia or more.[53] The (c. 1st century BCE) Shennong bencao calls "cannabis flowers/buds" mafen (麻蕡) or mabo (麻勃) and says: "To take much makes people see demons and throw themselves about like maniacs. But if one takes it over a long period of time one can communicate with the spirits, and one's body becomes light"[54] A 6th-century Daoist medical work, the Wuzangjing (五臟經, Five Viscera Classic) says, "If you wish to command demonic apparitions to present themselves you should constantly eat the inflorescences of the hemp plant".[51]

The Zhen'gao gives alchemical prescriptions for gaining visionary power, and Yang Xi describes his own reactions to using the Chushenwan (初神丸, Pill of Incipient Marvels) that contains much cannabis.[53] Both Yang and Xu Mi were regularly taking Chushenwan cannabis pills that were supposed to improve health by eliminating the Sanshi (三尸, Three Corpses) from the body, but which also apparently brought about "visionary susceptibility". In a letter to Xu Mi, Yang Xi asked if he had begun to take the pills. Of his own experience, Yang wrote in the Zhen'gao, "I have been taking them regularly every day, from the lot which I obtained earlier. I have not really noticed any special signs, except, at the very beginning, for six or seven days, I felt a sensation of heat in my brain, and my stomach was rather bubbly. Since then there have been no other signs, and I imagine that they must gradually be dealing with the problem".[52]

In addition to editing the official Shangqing canon, the Daoist pharmacologist Tao Hongjing also wrote the (c. 510) Mingyi bielu (名醫別錄, Supplementary Records of Famous Physicians) that records, "Hemp-seeds ([mabo] 麻勃 "cannabis flowers") are very little used in medicine, but the magician-technicians ([shujia] 術家) say that if one consumes them with ginseng it will give one preternatural knowledge of events in the future.".[55]

Some early Daoists used ritual censers for the religious and spiritual use of cannabis. The (c. 570) Daoist encyclopedia Wushang Biyao (無上秘要, Supreme Secret Essentials) recorded that cannabis was added into ritual incense-burners. The ancient Daoists "experimented systematically with hallucinogenic smokes, using techniques which arose directly out of liturgical observance".[56]

The (5th-6th century) Yuanshi shangzhen zhongxian ji (元始上真眾仙記, Records of the Assemblies of the Perfected Immortals), which is attributed to Ge Hong (283-343), refers to the Shangqing founders using qīngxiāng (清香, "delicate fragrance; purifying incense"). "For those who begin practicing the Tao it is not necessary to go into the mountains. … Some with purifying incense and sprinkling and sweeping are also able to call down the Perfected Immortals. The followers of the Lady Wei [Huacun] and of [Xu Mi] are of this kind." Needham and Lu say, "For these 'psychedelic' experiences in ancient Taoism a closed room would have been necessary".[53] Namely, the Daoist jìngshì (靜室, Quiet Chamber) oratory, which most early descriptions represent as almost empty except for an incense-burner.[57]

References

- Espessett, Grégoire (2008). "Yang Xi 楊羲". In Fabrizio Pregadio (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Taoism. Two volumes. Routledge. pp. 1147–1148. ISBN 9780700712007.

- Ledderose, Lothar (1984). "Some Taoist Elements in the Calligraphy of the Six Dynasties". T'oung Pao. 70 (4/5): 246–278. doi:10.1163/156853284X00107.

- Needham, Joseph; Lu, Gwei-djen (1974). Science and Civilisation in China. Volume 5: Chemistry and Chemical Technology. Part 2, Spagyrical Discovery and Inventions: Magisteries of Gold and Immortality. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-08571-3.

- Needham, Joseph; et al. (1980). Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology. Part 4, Spagyrical Discovery and Invention: Apparatus, Theories and Gifts. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521085731.

- Robinet, Isabelle (1984). La révélation du Shangqing dans l'histoire du taoïsme (in French). École française d'Extrême-Orient.

- Smith, Thomas E. (2013). Declarations of the Perfected: Part One: Setting Scripts and Images into Motion. Three Pines Press. ISBN 9781387209231.

- Strickmann, Michel (1977). "The Mao shan Revelations: Taoism and the Aristocracy". T'oung Pao. 63: 1–64. doi:10.1163/156853277X00015.

- Strickmann, Michel (1979). "On the Alchemy of T'ao Hung-ching". In Holmes Welch; Anna Seidel (eds.). Facets of Taoism: Essays in Chinese Religion. Yale University Press. pp. 123–192.

Footnotes

- ↑ Robinet 1984, pp. 107–8, cited by Eskildsen, Stephen (1998), Asceticism in Early Taoist Religion, State University of New York Press, p. 70.

- ↑ Smith 2013, p. 61.

- ↑ Smith 2013, p. 104; Strickmann 1977, p. 47.

- 1 2 3 Espessett 2008, p. 1147.

- 1 2 Strickmann 1977, p. 42.

- ↑ Strickmann 1977, p. 6.

- ↑ Strickmann 1977, p. 8.

- ↑ Smith 2013, pp. 15, 283.

- ↑ Needham et al. 1980, p. 214.

- ↑ Ledderose 1984, p. 255.

- ↑ Espessett 2008, p. 1148.

- ↑ Needham & Lu 1974, p. 110.

- ↑ Strickmann 1979, p. 138.

- ↑ Strickmann 1979, p. 6.

- ↑ Kohn, Livia (2007), "Daoyin: Chinese Healing Exercises", Asian Medicine 3.1: 103 –129. pp. 113-4.

- 1 2 Strickmann 1977, p. 41.

- ↑ Miura, Kunio (2008). "'Zhenren 真人 Real Man or Woman; Authentic Man or Woman; True Man or Woman; Perfected". In Fabrizio Pregadio (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Taoism. Two volumes. Routledge. p. 1265. ISBN 9780700712007.

- ↑ Strickmann 1977, p. 3; Espessett 2008, p. 1147.

- ↑ Strickmann 1977, p. 14.

- ↑ Ledderose 1984, pp. 262–3.

- ↑ Kohn, Livia (2008). "Meditation and visualization". In Fabrizio Pregadio (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Taoism. Two volumes. Routledge. p. 119. ISBN 9780700712007.

- ↑ Ledderose 1984, pp. 254, 256.

- ↑ Smith 2013, p. 16.

- ↑ Ledderose 1984, p. 254.

- ↑ Strickmann 1977, p. 10.

- ↑ Kim, Jihyun (2015)."The Invention of Traditions: With a Focus on Innovations in the Scripture of the Great Cavern in Ming-Qing Daoism", 道教研究學報:宗教、歷史與社會 (Daoism: Religion, History and Society) 7: 63–115. p. 68.

- ↑ Strickmann 1977, p. 16.

- ↑ Strickmann 1977, pp. 12–3.

- ↑ Needham et al. 1980, p. 216.

- 1 2 Strickmann 1977, p. 5.

- ↑ Pregadio, Fabrizio (2008). "Waidan "external elixir; external alchemy" 外丹". In Fabrizio Pregadio (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Taoism. Two volumes. Routledge. p. 1002 (1002-1004). ISBN 9780700712007.

- ↑ Russell, Terence C. (2005), Tao Hongjing, Encyclopedia of Religion, Thomson Gale.

- ↑ Strickmann 1977, p. 39.

- ↑ Strickmann 1977, p. 3.

- ↑ Ledderose 1984, p. 258.

- ↑ Strickmann 1977, p. 4.

- ↑ Needham et al. 1980, p. 215.

- ↑ Tr. Strickmann 1977, pp. 24, 41–2.

- ↑ Ledderose 1984, pp. 256–7.

- ↑ Strickmann 1979, pp. 140–1.

- ↑ Espesset, Grégoire (2008). "Tao Hongjing 陶弘景". In Fabrizio Pregadio (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Taoism. Two volumes. Routledge. p. 970 (968-971). ISBN 9780700712007.

- ↑ Strickmann 1977, p. 19.

- ↑ Strickmann 1977, pp. 17–8.

- ↑ Tr. Strickmann 1977, pp. 45–6.

- 1 2 Strickmann 1977, p. 23.

- ↑ Strickmann 1977, p. 27.

- ↑ Strickmann 1977, p. 25.

- ↑ Strickmann 1977, p. 28.

- ↑ Strickmann 1977, pp. 29–30.

- ↑ Ledderose 1984, p. 271.

- 1 2 Needham et al. 1980, p. 213.

- 1 2 Strickmann 1979, p. 172.

- 1 2 3 Needham & Lu 1974, p. 152.

- ↑ Tr. Needham & Lu 1974, p. 150.

- ↑ Needham & Lu 1974, p. 151.

- ↑ Needham & Lu 1974, p. 154.

- ↑ Needham & Lu 1974, p. 131.

Further reading

- Andersen, Poul (1989), "The Practice of Bugang", Cahiers d'Extrême-Asie 5.5:15-53.