The Yangzhou riot of August 22–23, 1868 was a brief crisis in Anglo-Chinese relations during the late Qing dynasty. The crisis was fomented by the gentry of Yangzhou who opposed the presence of foreign Christian missionaries in the city, who claimed that they were legally residing under the provisions of the Convention of Peking. Threats against the missionaries were circulated by large character posters placed around the city. Rumors followed that the foreigners were stealing babies and killing them to make medicine.

The riot that resulted was an angry crowd of Chinese estimated at eight to ten thousand who assaulted the premises of the British China Inland Mission in Yangzhou by looting, burning and attacking the missionaries led by Hudson Taylor. No one was killed, however several of the missionaries were injured as they were forced to flee for their lives.

As a result of the report of the riot, the British consul in Shanghai, Sir Walter Henry Medhurst took seventy Royal marines in a man-of-war and steamed up the Yangtze to Nanjing in a controversial show of force that eventually resulted in an official apology from the Chinese government under Viceroy Zeng Guofan and financial restitution was offered to the C.I.M. but not accepted, to create goodwill among the Chinese. The house that they had purchased in the city was however restored to the mission. Hudson Taylor and other Christian missionaries in China at that time were often accused of using gunboats to spread the gospel. However, none of the missionaries had requested or desired the military intervention.[1]

Prelude

There was an orphanage in Yangzhou operated by a French Roman Catholic where a number of infants had died of natural causes. However, this fueled the rumors that Chinese children were disappearing.[2]

Marshall Broomhall later noted regarding the cause of the riot:

In regard to riots in China the long-standing enmity of the literati of China to all things foreign must be remembered as well as the fact that the Chinese people were at that period " in the point of superstition very much where we were in the sixteenth century." Should the literati stir up the passions of the people by playing upon their superstitious fears, few officials had the moral courage as well as the ability to keep the peace for long, for their tenure of office was largely dependent upon the goodwill of the scholarly class. Du Halde tells of a book dated as early as 1624 which circulated the base and foolish charges of the foreigners kidnapping children, extracting their eyes, heart, and liver, etc., for medicine, and the Roman Catholic practice of extreme unction, and the habit of closing the eyes of the dead, may have given some basis for part of such a belief. In 1862 a book entitled Death-blow to Corrupt Doctrine a book republished at the time of the Tientsin massacre in 1870 brought forward similar charges. In 1866 Mr. S. R. Grundy, the Times correspondent in China, called attention to a proclamation extensively circulated in Hunan and the adjacent provinces. Clause VII. of this Proclamation read : " When a (Chinese) member of their religion (Roman Catholic) is on his death-bed, several of his co-religionists come and exclude his relatives while they offer prayers for his salvation. The fact is, while the breath is still in his body they scoop out his eyes and cut out his heart ; which they use in their country in the manufacture of false silver."[3]

About two weeks before the riot, a meeting of the literati was held in the city, and soon anonymous handbills were posted up throughout the city containing many absurd and foul charges. These handbills were followed by large posters calling the foreigners " Brigands of the religion of Jesus," and stating that they scooped out the eyes of the dying and opened foundling hospitals in order that they might eat the children. The Prefect had already been warned of the impending trouble, but did not take any action.

All possible conciliatory measures were adopted by the missionaries. Handbills were circulated promising the opening of the mission premises for inspection as soon as the workers had repaired the unfinished walls and removed the scaffolding which would be dangerous to a crowd.

The riot

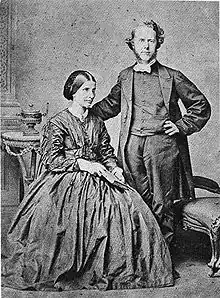

When the riot broke out the following members of the China Inland Mission were in Yangzhou : Mr. and Mrs. Hudson & Maria Taylor with four children (Herbert, Frederick, Samuel & Maria), Miss Emily Blatchley, Miss Louise Desgraz, Mr. and Mrs. William David Rudland, and Messrs. George Duncan and Henry Reid.

On Saturday, August 22, two foreigners came over from Zhenjiang to spend a few hours sight-seeing in the city, and almost immediately the city was full of wild rumors about the disappearance of as many as twenty-four children. By 4 P.M. the Mission premises were besieged. Messengers were dispatched to the Prefect, but with no effect. The passions of the crowd were growing, and at last, when the attack upon the premises had become full-scale, Mr. Taylor and Mr. Duncan determined to face the mob and try to make their way personally to the Yamen.

Mr. Taylor and Mr. Duncan, after having been badly stoned, reached the Yamen in an exhausted condition to find the terrified gatekeepers closing the gates; the doors gave way before the pressure of the mob when the missionaries rushed into the judgment hall crying Kiu ming! Kiu ming ! ("Save life! Save life ! "), a cry to which any official is bound to attend at any hour, day or night. They were kept waiting in an agony of suspense for forty-five minutes before they saw the Prefect, and then only to be provokingly asked, " What do you really do with the babies ? " ; this interview was followed by another agonizing delay of two hours before they learned that help had been sent, though even then they were told on their way back that all the foreigners left in the house had been killed.

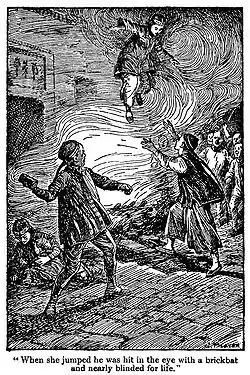

Those left in the mission house feared that the two who had faced the mob had been torn to pieces. When the house was set on fire from below the children and women had to be lowered from the upper story, and Mrs. Taylor and Miss Blatchley with their escape cut off had to jump, both were seriously injured. Mr. Reid was nearly blinded for life by being struck in the eye with a brick when trying to break Mrs. Taylor s fall.

That any of the party escaped to tell the tale was little less than a miracle. However, the whole party of missionaries, several of whom were severely wounded and weak from the loss of blood, were enabled on Monday, August 23, the anniversary of little Gracie Taylor's death, to journey down to Zhenjiang, where they were cared for.

Aftermath

On their way down to Zhenjiang the missionaries passed the Assistant British Consul and the American Consul on their way up. The Consular Authorities proceeded to investigate the situation personally, and reported their findings directly to William Henry Medhurst, the British Consul at Shanghai. Mr. Medhurst made prompt demands for reparation. Proceeding with an escort to Yangzhou he demanded that the Prefect should accompany him to Nanjing that the case might be judged before the Viceroy. The Prefect begged to be allowed to go in his own boat and not as a prisoner, and this was agreed to upon his furnishing his written promise not to escape. This he readily gave, yet fled under cover of darkness.

Even so, Mr. Medhurst proceeded to Nanjing with the gunboat Rinaldo as escort. In the course of the negotiations, which promised to terminate satisfactorily, the captain of the gunboat took ill and left for Shanghai. With the withdrawal of the gunboat the aspect of affairs immediately changed, and Mr. Medhurst had to depart diplomatically at a loss. This failure led Sir Rutherford Alcock to authorize Consul Medhurst to renew his demands, this time backed by a naval squadron. The Viceroy Zeng Guofan speedily came to terms, and appointed two deputies to proceed to Yangzhou and hold an enquiry. A proclamation was thereupon issued which secured the reinstatement of the mission, compensation for damages to property, and moral status in the eyes of the people by stating that " British subjects possess the right to enter the land," and that " Local Authorities everywhere are to extend due protection."

The British Foreign Office sharply criticized Medhurst and Alcock for having used gunboats to extract concessions from the Nanjing Viceroy. This was contrary to the British policy of holding the central government of China - not local governments - responsible for enforcing the commercial treaties and the safety of foreign residents in China. The incident prompted foreign secretary Lord Clarendon to officially censure Medhurst and Alcock for the actions, and to reiterate the policy of the British government to seek redress from Beijing whenever foreigners were attacked.[4]

The British press reacted critically of the missionaries working in China and blamed them for causing a crisis in Sino-British relations. There were heated debates in the British Parliament about whether missionaries should be allowed to continue to live abroad in China away from the Treaty Ports.[5]

Maria Taylor was among those who defended the actions of the China Inland Mission in the wake of the riot. She wrote to a friend in England:

In the riot we asked the protection of the Chinese Mandarin. . . . After our lives were safe and we were in shelter, we asked no restitution, we desired no revenge. I think I may say with truthfulness that we took cheerfully the spoiling of our goods. But a resident at Chinkiang, up to that time a perfect stranger to most of us, and only slightly acquainted with my dear husband, wrote stirring accounts to the Shanghai papers (without our knowledge), and public feeling demanded that action, prompt and decisive should be taken by our authorities. And this was taken unsolicited by us.[6]

On November 18 the Taylors were reinstated in their house at Yangzhou by the British Consul and the Taotai from Shanghai, who had come up as the Viceroy's deputy. For some time Yangchow became the home of Mr. and Mrs. Taylor despite the efforts of some high-placed officials to eject them. The Governor of Zhenjiang, however, personally purchased the mission premises from the anti-foreign landlord a high military official named Li.

See also

- Anti-missionary riots in China

- William Thomas Berger

- Nian Rebellion, final engagement happened in Yangzhou during the same year

Notes

References

- Austin, Alvyn (2007). China's Millions: The China Inland Mission and Late Qing Society. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2975-7.

- Broomhall, Alfred (1985). Hudson Taylor and China's Open Century, Book Five. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

- Broomhall, Marshall (1915). The Jubilee Story of the China Inland Mission. London: Morgan & Scott.

- Cohen, Paul A., China and Christianity: The Missionary Movement and the Growth of Chinese Anti-Foreignism, 1860-1870. (Harvard University Press, Cambridge: 1963)

- Fairbank, John King. "Patterns Behind the Tientsin Massacre." Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 20, no. 3/4 (1957): 480–511.

- Haar, Barend J. ter, Telling Stories: Witchcraft and Scapegoating in Chinese History, (Brill, Leiden: 2006) chap. 4, ‘Westerners as Scapegoats’ pp. 154–201.

- Howard Taylor; Mrs. Howard Taylor (1912). Hudson Taylor in Early Years: The Growth of a Soul. China Inland Mission.

- Taylor, Dr. & Mrs. Howard (1918). Hudson Taylor and the China Inland Mission: The Growth of a Work of God. London: Morgan & Scott.

- Taylor, James H. III (2005). Christ Alone: A Pictorial Presentation of Hudson Taylor's Life and Legacy. Hong Kong: OMF books.