The Yukaghir birch-bark carvings were traditionally drawn by Yukaghir people of Siberia on birch barks for various purposes such as mapping, record-keeping, and party games. Russian writers observed these carvings in the 1890s, and based on their descriptions, several 20th-century scholars misunderstood them to be the examples of a writing system. One particular carving became well-known as the "Yukaghir love letter", but is actually the product of a guessing game.

Types

Three kinds of Yukaghir carvings are known from the accounts of the Russian writers S. Shargorodskii and Vladimir Jochelson:[1][2]

- The so-called "Yukaghir love letters", which are actually product of a guessing game at social gatherings (see below).

- Small-scale maps drawn by men to assist in travels for hunting and other purposes. These maps used a limited set of symbols to depict features such as rivers and dwellings, so it appears that the Yukaghir men had established certain mapping conventions.

- Depictions of record-keeping: for example, Shargorodskii provides a picture, which according to a Yukaghir man, records that a Yukaghir woman made a shawl for him, and received payment in form of several items such as a comb, tobacco, and buttons.

According to John DeFrancis, the Yukaghir carving is "an example not of writing but of anecdotic art", whose meaning is clear only to someone who is in contact with the creator or another interpreter who understands its meaning.[1]

The so-called "Yukaghir love letter"

A notable example of the Yukaghir carving is a sketch by the Russian writer S. Shargorodskii (1895), reproduced by Gustav Krahmer (1896).[3][4]

Shargorodskii, a member of the revolutionary group Narodnaya Volya, had been exiled to Siberia by the Tsarist regime. He spent 1892-1893 in the Yukaghir village of Nelmenoye in the Kolyma river area, near the Arctic Ocean. He gained the trust of the local Yukaghir people, and joined them in social activities.[1]

In 1895, Shargorodskii published a 10-page article titled On Yukaghir Writing in the journal Zemlevedenie. Six photographs of the alleged Yukaghir writing system accompanied the article.[1] Shargorodskii obtained the picture of what later came to be known as a "love letter" from a Yukaghir party game, similar to charades or twenty questions.[4][3] He states that he observed such pictures being made during social gatherings: a young girl would start carving on a fresh birch bark, and the onlookers made guesses about what she was depicting. Eventually, after several incorrect guesses, all the participants in the game would arrive at a common understanding of the picture. Since the participants knew each other well, they could easily deduce the meaning of the carvings; it was not easy for the outsiders to understand the meaning, but Shargorodskii could do so with the help of his Yukaghir acquaintances. According to Shargorodskii, such birch bark carvings were drawn only by young women, and only discussed love lives.[1]

In 1896, General-Major Gustav Krahmer published a translation of Shargorodskii's article in the geographical journal Globus. Shargorodskii had referred to the pictures as "writings" and "figures", but Krahmer presented them as "letters". In 1898, Shargorodskii's friend Vladimir Jochelson, a political exile turned ethnographer, published another example of the Yukaghir carving. Subsequently, several other writers reproduced these pictures. Jochelson wrote that the Yukaghir men often visited the Russian settlement of Srednekolymsk for various purposes; the Yukaghir pictures were expressions of sadness by the jealous Yukaghir girls, who were concerned about losing their lovers to Russian women during such visits.[1]

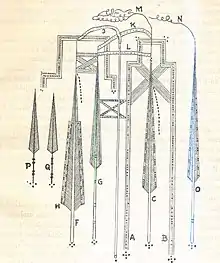

German writer Karl Weule (1915) published a slightly different version of the Shargorodskii's picture, drawn by the artist Paul Lindner, with the caption "Yukaghir Love Letter" in a popular museum booklet.[1] Thus, Weule appears to have been primarily responsible for promoting the idea that the Yukaghir pictures represent love letters.[4] David Diringer's widely-read book The Alphabet (1948) included an illustration, likely based on Weule's work, with the caption "Sad love-story of a Yukaghir girl".[1] According to one interpretation, the arrow shapes represent four adults and two children. The solid and broken lines connecting the arrows represent current and previous relationships between the adults.[5]

The so-called "Yukaghir love letter" was alleged to be the best example of ideographic picture writing for years.[4] British linguist Geoffrey Sampson (1985) included a modified version of this sketch in his Writing Systems.[3] Sampson described the sketch as a love letter sent by a Yukaghir girl to a young man, presenting it as an example of a semasiographic writing system, which is capable of "communicating its meaning independently of speech".[4]

Although Sampson did not mention his source, American linguist John DeFrancis (1989) traced it to Diringer, and ultimately Shargorodskii.[3][4] DeFrancis asserted that the pictures were not letters, but the product of a party game, in which young women could publicly express their feelings about love and separation to a small circle of friends in a socially acceptable way.[1] In a Linguistics article, Sampson admitted that the picture was "not an example of 'communication' at all", and that he had taken the picture (and its interpretation) from Diringer.[6]

Apparently unaware of DeFrancis' work, art historian James Elkins (1999) described the Yukaghir pictures as "diagrams of emotional attachments" and "texts, because they tell stories".[4] American linguist J. Marshall Unger dismisses this interpretation as inaccurate.[4]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 John DeFrancis (1989). "A Yukaghir Love Letter". Visible Speech. The Diverse Oneness of Writing Systems. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 24–34. ISBN 0824812077.

- ↑ Waldemar Jochelson (2018). Erich Kasten; Michael Dürr (eds.). The Yukaghir and the Yukaghirized Tungus. SEC. pp. 434–447. ISBN 9783942883900.

- 1 2 3 4 J. Marshall Unger; John DeFrancis (2012). "Logographic and Semasiographic Writing Systems: A Critique of Sampson's Classification". In Insup Taylor; David R. Olson (eds.). Scripts and Literacy: Reading and Learning to Read Alphabets, Syllabaries and Characters. Neuropsychology and Cognition. Vol. 7. Springer. pp. 47–48. doi:10.1007/978-94-011-1162-1_4. ISBN 978-94-010-4506-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 J. Marshall Unger (2003). "Cryptograms vs. pictograms". Ideogram: Chinese Characters and the Myth of Disembodied Meaning. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 21–25. ISBN 0-8248-2656-6.

- ↑ Nicola Brunswick; Sine McDougall; Paul de Mornay Davies (2010). Reading and Dyslexia in Different Orthographies. Psychology Press. p. 5. ISBN 9781135167813.

- ↑ Geoffrey Sampson (1994). "Chinese script and the diversity of writing systems". Linguistics. 32: 117–132. doi:10.1515/ling.1994.32.1.117. Retrieved 2023-02-22.