Haji Zakaria bin Muhammad Amin | |

|---|---|

_(cropped).jpg.webp) Zakaria in 1986 | |

| Born | Zakaria 7 March 1913[Note 1] Bangkinang, Dutch East Indies |

| Died | 1 January 2006 (aged 92) |

| Nationality | Indonesian |

| Occupations |

|

| Political party | Masyumi (1943–1960) PPP (1974–1986) |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 14, including Nukman, Gamal and Rita |

| Relatives | Tuan Guru Haji Ahmad (father-in-law) Abdul Karim Ahmad (brother-in-law) Muhammad Yahman (son-in-law) Wisra Okarianto (grandson) |

Haji Zakaria bin Muhammad Amin (7 March 1913[Note 1] – 1 January 2006) was an Indonesian ulama, politician, and writer from Bangkinang, Kampar. He was an ulama in Bengkalis Regency, and was the first head of Islamic religious administration in Bengkalis. Zakaria was the son in law of Tuan Guru Haji Ahmad, the first ulama of Bengkalis Regency. In 2023, he was posthumously awarded the title of Regional Hero of Riau by the Riau Regional People's Representative Council.

Early life and education

Zakaria bin Muhammad Amin was born on 7[Note 1] March 1913 in Bangkinang, Kampar, as the eldest child and son of the three children of Taraima, a seamstress, and Muhammad Amin (d. 1930s), a trader, both from Kuok, a village near his birth place.[2] He had three brothers and two sisters: Hasyim bin Muhammad Amin, Ahmad bin Muhammad Amin, Siti Mariam binti Muhammad Amin, Syarafiah Norwawi binti Muhammad Amin (1935–2002), a homemaker, and Ahmad Sanusi bin Muhammad Amin (d. 2022), a journalist; three of them are paternal half-siblings.[3] All of them were educated at Volks School due to difficulty in continuing higher education during colonial period, and later resided in Kuala Lumpur as a farmer and glassware dealer, and earned Malaysia citizenship in the 1960s.[3] Their parents were clothing traders in the market and moved from one village to another along the Riau-West Sumatra road to sell their wares.[2] Apart from working as a trader, they also have a herd of buffalo as livestock to graze on the rice fields they own.[2]

Zakaria spent his childhood herding buffalo in the rice fields and played the gambus.[4] He was raised in a religious and discipline environment where he wakes up every day at 4 am and helps prepare his parents' merchandise, then performs morning prayers in congregation followed by looking after the buffalo for a day.[5] His parents teach him and his siblings to be honest, does not disturb other people, gives in when disturbed by others, does not hurt others, and likes to help those in need.[6] Zakaria also liked to playing marbles, kites and swimming in the Kampar River with his friends, which is not far from the rice fields where his livestock graze.[7] He was referred as a kind person and make friends without distinction, and being familiar with all of his friends.[8] During his childhood, he feels that he has no specific speciality compared to his other siblings.[6] Even so, his parents did not differentiate the affection between him and his siblings so they all got along very affectionately.[6] He stated in his later years that the spirit of hard work and religious devotion possessed by his parents left a special impression on him.[1]

Zakaria began his schooling in 1920 at Tweede Inlandsche Public School in Bangkinang, during the period of Dutch colonialism.[9] He later dropped out at third grade and uninterested to continue due to considers religious knowledge to be more important than scientific knowledge.[9] In 1923, at the age of 10, he travelled to Mecca as part of the hajj along with his maternal aunt, Fatimah, who later died in her hometown as of 1991.[10] They travelled with Fatimah's husband, Abdullah, using a ship from Port of Teluk Bayur in Padang.[9] The trip exhausted Zakaria due to the ships that belonging to the Dutch East Indies government often stopped at a number of ports, including in its colonies, so the journey took around about three to four months.[11] After arrived in Mecca, Zakaria and his uncle got to know many pilgrims from British Malaya.[12] They then performed the Hajj and studied religious knowledge with famous sheikhs there.[12] Zakaria continued his education by studying with the scholars in Mecca such as Ali Al-Maliki, Syekh Umar Al-Turki, Umar Hamdan, Ahmad Fathoni, and Syekh Muhammad Amin Quthbi.[12] He then studied various of islamic knowledge such as Interpretation of the Quran, Hadith, Tawhid, and Arabic literature together with pilgrims from various countries using the Halaqa method after doing a prayer.[12] His sanad can be traced from the teachings of Syekh Ahmad Khatib Al-Minangkabawi, a Shafi'i scholar at Masjid al-Haram who was the teacher of Ahmad Dahlan, founder of Muhammadiyah, and Hasyim Asy'ari, founder of Nahdlatul Ulama.[12]

After he completed his studies in Mecca, Zakaria moved to British Malaya with his aunt and uncle due to the country being quite famous for its strict implementation of Islamic teachings.[12] He continued his Islamic knowledge study in Temerloh, Pahang, for six years under Muhammad Saleh, until Saleh, whose father was of Arab descent and mother from Pahang, died.[12] Zakaria studied Matan Jurumiyah, an Arabic literature book, with Saleh until finished.[12] He then moved to Kuala Lipis, a district in Pahang, for nine months but moved after it flooded at the end of 1929.[12]

Due to floods that hit the area, Zakaria and his friends moved to Bengkalis, the capital city of Bengkalis Regency, Riau.[12] He then arrived at Parit Bangkong Grand Mosque and continued his Islamic study with Tuan Guru Haji Ahmad, the first ulama in Bengkalis Regency.[13] Zakaria then taught at the mosque along with several of his friends, including Muhammad Toha, Muhammad Sidik, and Muhammad Ismail.[13] With a suggestion from Ahmad, he then moved to Bagan Datuk, Perak, after his marriage with Ahmad's daughter, Mariah, in 1933, to continued his Islamic education there.[13]

Military career

During the Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies, he led the resistance movement there along with Abdullah Nur and nationalists in Bengkalis.[14] He and Nur campaigned to raise people's spirits using the theme bubbun watal minal iman (English: loving one's homeland is part of faith).[14] They then formed a joint association with community leaders from various religions and delivered the "Sumpah Setia Perjuangan" (literally Oath of Allegiance to the Struggle) led by Judge Ahmad Khatib for the Islamic side and Joseph Hutabarat, former Head of Workshop and Shipping during the Dutch Colonial Period, for the Christian side.[14]

During the 1948 Dutch invasion of Indonesia, the Dutch Navy carried out initial attacks on Bengkalis, Selat Panjang, and its surroundings on 29 December.[1] Zakaria led the resistance movement together with Indonesian National Army troops in Bengkalis, in 1949, as a Titular Mayor.[15] Although Tanjung Pinang, Pekanbaru, Bengkalis, and the surrounding areas were later occupied by Netherlands Indies Civil Administration, Bengkalis City was successfully defended by several military units under the leadership of Lieutenant Mansur, a headquarters military unit led by Endut Gani, and a headquarters platoon along with a detachment of army police who were ordered to prioritize defense in the sea area because it prevents enemy troops from landing.[1] After surviving for one and a half months guerrillas in Bengkalis surrounding several villages such as Kelapapati, Pedekik, Bantan Tua, Selat Baru, etc, Zakaria together with the Indonesian National Army troops then moved to Sumatra.[1] They later moved to Dumai after received order from central government (which consist of Sudirman, Djatikoesoemo, and Abdul Haris Nasution), Zakaria then joined and was given task to continued leading the resistance movement, and later received the honorary title of Mayor.[16]

Scholarly career

Zakaria started his career as a preacher and teacher at religious school owned by Tuan Guru Haji Ahmad near Parit Bangkong Mosque in Parit Bangkong, Bengkalis, at the age of 16, and devoted himself to becoming a teacher at the school and mosque.[13][17] In this school, he meet with Abdullah Nur, who was arrived from Langkat and will became the future Chairman of the Indonesian Ulema Council in Bengkalis.[17]

In 1930, one year after returning from British Malaya, he began to write two books: Balqurramhi fi Sunniyyati Qunut Subhi, which discussed the issue of the qunut prayer at the morning prayer, and Kumpulan Khutbah Jumat dan Hari Raya Sebanyak Dua Belas Judul Khutbah.[18] These two books discuss Zakaria's opinions on the issue of Salah, which was a popular subject of Islamic academic discussion at that time and was released by At-Tabib magazine in Cikampek, in 1930, and Hidah Benar magazine in British Malaya, in 1939.[19] Zakaria also wrote about the problem of usholli in prayer in At-Tabib magazine in 1932 and wrote about the problem of the tarawih sunnah prayer rakaat in Hidah Benar magazine in 1939.[19] According to Zakaria, the khilafiyah issue is not only a topic of discussion within the country but also an international discussion, such as in British Malaya.[1] He said in an interview that as someone who had studied in Mecca and British Malaya, he felt burdened with the obligation to explain the solution to the problem proportionally so that no party blamed each other in discussing the problem.[1] However, due to his moving life during the aggression period, his books were lost and could not be found again.[1] After national condition began to improve, Zakaria began to wrote Kumpulan Muhadaroh Untuk Anak-anak Madrasah dalam Bidang Fiqih, Akhlak, Tauhid, dan sebagainya which then became a handbook for his students in learning at the school managed by him.[1]

In 1937, after finished his study in Perak, he along with Tuan Guru Haji Ahmad established Al-Khairiyah, the first Islamic boarding school located in a land owned by Abdul Rahman at Sulthan Syarif Kasim Bengkalis street in Bengkalis Regency, and became the school leader.[13] Being the first, it drew students from many regions of Riau to study there, such as from Selat Panjang, Bagan Siapi-api, Rupat, Tanah Putih, Merbau, Sungai Apit, Bukit Batu, Bangkinang, and etc.[16][20] He continued preaching and teaching his students at Al-Khairiyah using a classical system and at various mosque in Bengkalis, until Al-Khairiyah was closed in 1943 due to the Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies already spread to Bengkalis.[15] The teaching and learning activities were stopped and the students were returned to their respective areas of origin.[17] The former Al-Khairiyah building later became the Dayang Dermah Orphanage.[16]

During Operation Kraai, Zakaria provided religious education during his breaks from fighting by moving from one house to another in several villages, such as Kelapapati, Pedekik, and Wonosari.[1] After the war ended, he returned to continuing his activities of providing religious education on the terrace of his house.[1] In December 1949, he was appointed by Bengkalis Regent, Muhammad, to became the first head of Islamic religious administration in Bengkalis and assigned to help develop the religious sector in Bengkalis.[15][16] From 1950 until 1972, he was the Head of the Bengkalis Regency Religion Department Office, and was the first person to hold the position.[15] He later became a judge for the district level of Musabaqah Tilawatil Quran in Bengkalis, from 1964.[15] He also worked as a lecturer in the field of Religious Teacher Education at YPPI Bengkalis from 1964 until 1970 when the school was closed.[15]

On 17 July 1963, Zakaria established MDTA Mahbatul Ulum, a Islamic school for children and young adults located at Gerilya Street in Kelapapati Darat which provides educational levels at Ibtidaiyah (junior school), Tsanawiyah (middle school), and Aliyah (high school) levels.[15] This school had six classrooms when first built, which is used to carry out educational activities for six years at Ibtidaiyah level, three years for Tsanawiyah level, and three years for Aliyah level and were used for teaching various Islamic disciplines such as Nahwu Shorof, Fiqh, Tawhid, Akhlaq, Hadith, Tarikh, and Interpretation of the Quran, using a classical education method.[21] There is also a classroom on the second floor which is used as a prayer room to carry out Asr prayers when the students are resting at 15.30 PM.[22] In this room, the male students who are already at the Aliyah grade and have fulfilled the requirements take turns being the Asr prayer leaders as well as practicing the reading of the wirid and prayers that have been taught in class lessons.[23] On Sunday and holidays, such as the birthday and Isra Mi'raj of the Prophet Muhammad, the prayer room is used as a place to practice speeches in Arabic for the Aliyah class and speeches in Malay Arabic for the Tsanawiyah class while using verses from the Qur'an or prophet hadith in the concept of the speech.[23] Mahbatul Ulum was reportedly successful in teaching, directing, and motivating its students to become preachers in the religious field, and was used as a place to celebrate religious events in Bengkalis.[23] At the beginning of the construction, MDTA Mahbatul Ulum only has seven classrooms which do not have complete walls and only have dirt floors due to Zakaria's limited capabilities from the assistance provided by the local community.[23] The school floor was renovated and harden in 1977 by Bengkalis regent, Himron Saheman, at a cost of Rp 350.000 (USD 23).[23]

In 1986, during the preparations for the 1987 elections, the school underwent second round of renovations with the help from Riau Regional Government, at a cost of Rp 9.600.000, which was used to rehabilitate classroom walls that had experienced heavy damage and renovate three classrooms and their ceilings.[23] A third round of renovations took place in 1989 as part of the Abri Masuk Desa program created by President Suharto which targets the object of improving the social environment and places of worship, including MDTA Mahbatul Ulum, which then succeeded in rehabilitating four classes by replacing damaged walls and installing them with new walls.[23] Bengkalis Regional Government through the Local Revenue Fund Education Facility Assistance Project (Proyek Bantuan Sarana Pendidikan Dana Pendapatan Asli Daerah) from 1990 to 1991, build four additional classes including a prayer room above Aliyah class to support religious education facilities from schools that specifically teach religious education and was completed in early 1991.[18] On Islamic holidays, such as the Prophet's Birthday, Isra Mi'raj, and etc, MDTA Mahbatul Ulum is used as a place of activity to train students' abilities and improve social relations between parents and teachers, as well as to hold deliberations to discuss matters of increasing educational costs.[18] In 1991, through a large deliberation, it was decided that the education contribution fee for two academic years would be Rp. 1000 for each student as well as donors who are able to contribute continuously according to their ability.[18] After collecting funds for a month, a donation was given to the school from 263 parents of students and 40 regular donors, to pay the salary for nine permanent teachers with each person contributed more than Rp.1000, totalling more than Rp. 500.000.[18]

Zakaria used a classical education system in managing MDTA Mahbatul Ulum, with each teacher being individually responsible for the teaching methods used in their class.[19] The school academic year used the Islamic calendar system, which starts in Shawwal and ends in Sha'ban, with a full month of holidays in Ramadan.[19] The exam process at the school is not carried out using a quarterly chess system but is carried out directly every semester.[19] Zakaria served as school principal, and as the supervisor of teaching and learning process for the third grade of Tsanawiyah and Aliyah class.[19] His friend, Ustaz Ali Buyung, served as the vice principal and the supervisor for the first grade. The rest of the school staff such as Amri Almi, a supervisor for Tsanawiyah first grade, Abdul Hamid Asy'ari, a supervisor for Tsanawiyah second grade, Suhailis, a supervisor for Ibtidaiyah six grade, Sulaiman, a supervisor for fifth grade, Rita Puspita, a supervisor for fourth grade, Ahmadi, a supervisor for third grade, Harani, a supervisor for second grade, and Abdul Jalil Abbas, a supervisor for Ibtidaiyah first grade, which eight of them also served as the supervisors for the eight other year levels.[19] Almi also served as the school secretary.[19] Zakaria emphasized that the MDTA Mahbatul Ulum curriculum must teach religious lessons for 100 percent.[19] In leading the school which consists of 263 students and 9 teachers, he advised that the curriculum should not be changed again.[21] Even though there is a plan to implement a religious learning pattern of 30% and a general learning pattern of 70% designed by the Ministry of Religion in a joint decree with the Ministry of Education and Culture, Zakaria still insists on implementing 100% religious learning.[21] According to his students, the application of religious learning at 30% is completely insufficient.[21] He then added that according to the public, learning about the Islamic religion must always be carried out and guided 100 percent throughout life.[21] To implement the concept of 100 percent religious education, Zakaria compiled a detailed list of lessons so that it complies with Islamic religious education standards.[21] For the sixth class of Ibtidaiyah, he taught nahwu lessons using the book Mukhtasharjiddan, shorof using the book Kailani, fiqh using the book Fiqhul Wadhih volume two, tauhid using the book Jawahirul Kalamiyah, morals using the book Akhlaqun Nabi volume two, Hadith using the book Bulugul Maram, date using the book Khilashoh Nurul Yaqin volume two, translation of the Al-Qur'an using the book Mahmud Yunus, and Arabic using the book Durusul Lughah.[21] Meanwhile, for the third class of Tsanawiyah, he gives lessons from Monday to Saturday consisting of Nahwu using the book Qatrun Nada, shorof using the book Majmu'usyarif, Fiqh using the book Fathul Qarib, Ushul Fikih using the book Lathaiful Cues, tafsir using the book the book Jalalain, Hadith using the book Mukhtaru Shoheh Bukhori, tauhid using the book Kitafayatul 'Awam, Ma'ani and Bayan using the book Al-Balaghatul Wadhihah, Tarikh using the book Atmamul Wafair, and Arabic language lessons using the book Durulus Lughah.[21] And for the third grade Aliyah, Zakaria provided a lesson schedule consisting of Nahwu and Shorof material using the book of Ibn 'Aqil, Tauhid with the book Dasuki, Fiqh using the books Kifayatul Akhyar and Bidayatul Mujtahid, Ushul Fiqh using the book Lathaiful Icuas and Hudhorobik, tafsir using the Tafsir Jalalain and Al-Maraghi books, hadith using the Shohih Muslim book, and Mantiq lessons using the Audhohul Mabhum book.[24] By providing this learning material, Zakaria hopes that his students will be able to know, understand and implement the material that has been presented through practice and memorization every day.[25] He also hopes that with the material provided, his students can gain knowledge that is useful for their lives in this world and for facing life in the afterlife.[25] As of Zakaria's death, the school no longer provides the 100 percent religious education and uses the curriculum established by the Ministry of Religion.[25]

The courtyard of MDTA Mahbatul Ulum, which is quite large, is used by Zakaria and the society as a place for prayers during Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha.[1] During the prayer, Zakaria will provide spiritual advice to the community through sermons and campaign so that the community always pays attention to their children's education, especially religious education.[1] He added that religious education will guarantee happiness in the world and the hereafter, because whatever the journey of a person's life in this world, he will eventually return to meet God to be accountable for all his actions during his life.[1]

Zakaria, who was also called Abah by his students, became a religion teacher at musholla in Sri Pulau, Bengkalis, in 1964.[19] In 1984, he established Al-Ishlah mosque about 50 meters from his yard and later became a teacher at the mosque.[1] Apart from actively teaching in these two places, Zakaria is also active in giving recitations in several other mosques and prayer rooms.[1]

Political career

Zakaria was a member of the Masyumi Party lead by Muhammad Natsir until it was banned on 15 August 1960, by President Sukarno, for supporting the PRRI Rebellion.[26] After that, he then worked as an administrator of Nahdlatul Ulama in Bengkalis Regency and is active due to considers the organization that fight for Islam to be relevant with his political views.[15][26] He was a member of the People's Representative Council (DPR) in Bengkalis in 1955.[27]

To prepare materials to be taken to the Decentralization Conference and Conference of Regional People's Representative Councils throughout Indonesia which will be held from 10 until 14 March 1955 in Bandung, Zakaria attended the 8th plenary session held by the Bengkalis Regional People's Representative Council on 25 February and then resulted in a decision to convey the demand that the Riau region should be made into one province.[28] The demand was then successfully conveyed at the conference and received supporting votes from the Regional People's Representative Council throughout Riau.[28]

When Central Sumatra became a stronghold of the PRRI at the same time as preparations for the election, four regional People's Representative Councils throughout Riau consisting of Kampar, Bengkalis, Riau Islands and Indragiri held a conference on 7 August 1955 in Bengkalis lead by Mas Slamet with Zakaria as one of the delegation from Bengkalis who signed a petition for the former Riau province to be separated from Central Sumatra and demanded that Riau's autonomous status as an independent province be immediately granted.[28] Zakaria was then sent as a delegate from Bengkalis to meet the central government to convey requests for the results of the conference.[29] After two years of diplomation, the demand was finally fulfilled on 9 August 1957, when the Indonesian government issued Emergency Law Number 19 of 1957, which concerning the Formation of Level I Regions and divided Central Sumatra into three provinces; Riau, Jambi and West Sumatra.[29] The law was then signed by President Sukarno in Denpasar, Bali, and then inaugurated on 10 August 1957 until it was merged into Law Number 61 of 1958 concerning the Establishment of Emergency Law Number 19 of 1957 concerning the establishment of level I autonomous regions on 25 July 1958.[30]

From 1974 until 1986, he worked as a councillor, representing the United Development Party.[15] As of 1991, Zakaria is already retired from politics and only carried out learning and teaching Islamic religious activities to his students.[1]

Public image

Zakaria was referred by public as a figure who has the ability to socialize in society as an educator and religious leader, and has high knowledge and a proficient command of the Arabic language.[1] He often sends correspondence letters abroad, especially the Middle East, and is always a source of inspiration and motivation to work harder for his juniors.[1] He was a personal figure who is simple and dignified, consistent in every attitude and action, and was a productive community figure in every religious activity in Bengkalis District.[8][1] Abdullah Nur, whom at that time served as Chairman of the Bengkalis Regency Ulama Council, said that Zakaria is his friend when he returned from Langkat and was already teaching at the Parit Bangkong Bengkalis Grand Mosque when he returned from British Malaya.[1] He said that Zakaria was a figure who had extensive knowledge of religious knowledge, was persistent, persistent, tenacious, steadfast and selfless, and added that it was difficult to find a figure like him in this day and age.[1] Zakaria's work spirit is still unbeatable by anyone and Nur said that he is a more moderate figure than himself.[1] Ustaz Mil, Chairman of the Islamic Da'wah Council of Bengkalis Regency, in an interview on 25 July 1991, said that Zakaria is his friend when he returned from Ganting Village, Padang Panjang, and always discussed and exchanged ideas with him about religious matters.[1] He said that Zakaria was a figure who had interesting views and mastered the Yellow Book perfectly and was always firm in his stance.[1] Darmawi Karnadi, Head of the Bengkalis Regency Religion Department Office, whom was interviewed on 26 July, said that Zakaria, who was appointed as the first Head of the Bengkalis Regency Religious Affairs Office from 1950 until 1972, was the head of the office who served the longest in the ranks of the religious department.[1] He also added that Zakaria is a hard worker, tough, and has extensive knowledge.[1] Lumban Hutabarat, Chairman of the Bengkalis Religious Court, during an interview on the same day, said that Zakaria is a figure who should be emulated in his struggle to educate and guide the younger generation of Muslims in religious knowledge through the educational methods he developed.[1] He also praised Zakaria's enthusiasm for not fading even though he is old and is actually increasingly enthusiastic about advancing the quality of education at MDTA Mahbatul Ulum.[1]

Amri Almi, Secretary of MDTA Mahbatul Ulum, said that Zakaria is a true educator and added that he was a humble figure, had extensive knowledge, and was a role model and a place to ask questions, especially in the field of religion.[1] Zakaria's son, Gamal Abdul Nasir Zakaria, said that Zakaria is a democratic father, patient, and instills honesty in his children and gives them freedom, such as in choosing a school.[1] He taught religious knowledge to his children since they young and was a parent, teacher and friend in every discussion with them.[1] Alwi, Bengkalis District community figure, said that Zakaria is an honest person, simple in appearance, diligent in his work, respects other people's opinions, and was knowledgeable person but humble.[1] Fatah Lingga, Head of the Bengkalis District Health Service, said that the lecture delivered by Zakaria was very touching and easy to understand so that listeners would not get bored of listening to it.[1] Abdullah HM, an ulama and Principal of YPPI Bengkalis School, said that Zakaria was a person who was diligent, honest and discipline n teaching.[1] During the time he taught at YPPI, a lot of knowledge was passed on to his students and he became one of the scholars with the highest knowledge of religion at the school.[1] Wan Nasir, Head of Kelapapati Bengkalis Village, said that the existence of MDTA Mahbatul Ulum really helps Kelapapati Village and Bengkalis District.[1] He added that the children in the village can finally learn religious knowledge as well as possible so that they become an example for other villages to improve the quality of education in the community.[1] Suhaimi Thalib, Head of the Bengkalis Regency Education and Culture Service, said that Zakaria is an ideal figure for the younger and older generations as an example of perseverance and strong determination so that he succeeded in realizing his dreams well and as proof of his high dedication in serving to educate the nation's life in religious education.[1] He added that Zakaria had contributed as much as he could and it was the duty of other parties to follow up according to their respective professions.[1]

Views

Political views

Zakaria was a conservative and adhered to Ahlus Sunah Wal Jamaah, a political view of Nahdlatul Ulama which was based on understanding of the creed guided by the sunnah of the prophet Muhammad Sunni Islam.[25] In politics, Zakaria prioritizes campaign for the Islamic religion and adheres to Islamic political views.[26] He joined United Development Party because the party views at that time was still based on Islamic politics.[26]

During his time as a councillor for the United Development Party in the New Order, Zakaria was often offered for a position in People's Representative Council (DPR) but refused, stating that his purpose in joining politics was just to help Islamic parties with their campaigning.[26] When his friends such as Abdullah Nur and Ustaz Mil joined Golkar, he refused to follow them, as he felt it would be contrary to his views.[26] They however remained friends, with Zakaria stating that politics could not break their friendship.[31] He added a statement that "politics is just politics, friendship remain paramount and cannot be polluted by worldly lust and the nature of putting each other down".[31] Even though Zakaria was not involved in the management of the Indonesian Ulema Council like his friends who were close to the government, he did not feel disappointed and then chose to continue his preaching activities.[31]

Zakaria is a supporter of New Order and was one of the people who never opposes government policies.[31] When Fadlah Sulaeman became Bengkalis Regent, Zakaria was one of the person who has never had a dispute against him.[31] He never sent a crowd to criticize and embarrass the government if there were mistakes made during his term of office, but instead he would meet directly and convey suggestions using the mau'izhah hasanah method, a persuasive method to approach.[31] If the government ignores his advice, he never gets angry and will only respond that it is his duty as a cleric and he is only carrying out that duty.[31] After all parties and organizations established Pancasila as the only ideology that society must follow, Zakaria then resigned from the unity development party and returned to focusing on developing Islamic schools and teaching religious knowledge.[31]

Theology

Zakaria was a devout Muslim and was a follower of the Madhhab al-Shāfiʿī school of thought due to Imam Shafi'i who was an initiator and originator of the science of Ushul Fiqh which is the basis for many sharia laws and is one of the imams whose opinions are most widely and carefully paid attention to.[25] Even though he is a fanatical follower of Imam Shafi'i, he acknowledged the existence of four other Imams of the Madhhab school.[25] Zakaria's views on Islamic theology such as the caliphate tended to be moderate, and doesn't want to impose his opinions on other people regarding the matter due to prioritized discussions of the issues of brotherhood in Islam.[26] He said that discussions about Islamic political views should not lead to arguments as fellow Muslims which could result in a breakdown in solidarity.[26] Based on the matter, he gave an example from the lives of four school imams and stated that the four Imams of the Madhhab never say their opinion is the most correct, and always ready to discard their opinion if they learn of a more accurate one.[26] On the education matter, Zakaria stated that whatever a person's profession he still has to teach, because according to his religious views, even though a person only has a little knowledge but he can teach that knowledge to other people, even if it is only to one person and the knowledge is applied by the person he is teaching, the knowledge will be the only thing that can save his life in world and in the afterlife.[32]

Marriage and family relationships

Zakaria married his first wife Mariah binti Ahmad in 1933. Mariah was the daughter of Zakaria's teacher Tuan Guru Haji Ahmad and his first wife, Rohimah binti Sani.[3] Their marriage lasted until Mariah's death in 1955, due to illness after the events of the Dutch invasion of Indonesia.[3] They had three sons, Nashruddin (1934–1999), a civil servant and former employee of the Bengkalis Regency Department of Religion Office, Azra'ie (1947–2019), a lecturer at Asysyafi'iyah University in Jakarta, and Syakrani Zakaria (b. 23 November 1952), a harbormaster at Bengkalis Harbor, and four daughters, Aminah (1938–2011), a school principal formerly at SMP Negeri 2 Bengkalis, Zaharah (1942–2007), a politician from Golkar who served at People's Representative Council in Bengkalis from Development Works Fraction, Ulfah (b. 14 April 1943), a gynecologist at Manado General Hospital, and Hanim Zakaria (b. 11 September 1950), a junior school teacher in Pekanbaru.[3] After Mariah's death, Zakaria suffers from a heartbreak which he referred as the saddest heartbreak due to Mariah's loyalty who always accompanied him during the revolutionary period faithfully and steadfastly facing all the trials of life even though he was in a difficult situation.[33]

In order to provide a good care for his young children, Zakaria married his second wife, Siti Zainab binti Kimpal, 22 years his junior, in 1956.[9] Zainab was an Indonesian actress and singer from the Ratu Asia Troupe, and was known for her work in 1940s and 1950s Singapore films.[34] Their marriage lasted until Zakaria's death in 2006.[9] They had three sons, Zulkarnain (b. 17 August 1957), a civil and Nukman (b. 20 June 1960), both are civil servant at Department of Agriculture in Pekanbaru and Department of Agriculture and Food Crops in Bengkalis, respectively, and Gamal Abdul Nasir Zakaria (b. 22 June 1965), an Arabic and Islamic education lecturer at Universiti Brunei Darussalam, and four daughters, Rinie Yuslina Fairuz (1964–2021), and Rita Puspa (b. 20 November 1967), both are civil servant at RSUD Bengkalis with Rita served as Deputy Director of Services, Nida Suryani (b. 15 April 1971), a science teacher at SMP Al-Amin Bengkalis, and Sri Purnama Zakaria (b. 20 October 1973), an English teacher at SMA Negeri 2 Bengkalis.[9][35]

In raising his children, Zakaria educated them to have a simple and dignified attitude in every behavior and deed.[8] He adheres to religious principles in raising his family, one of which is that a newborn child must have the call to prayer in the right ear and the prayer in the left ear so that the first thing the child hears is the name of Allah.[1] He also prioritizes his children to implement practices that prioritize solving religious problems first before solving other matters.[1] He taught his children religious education since they were three years old with study time starting in the morning after the Fajr prayer, in the afternoon after the midday prayer, and in the evening after the Maghrib prayer.[1] After his children became proficient in reading the Quran and mastered Arabic, Zakaria then sent them to elementary school and gave them further lessons in the afternoon so that his children, who were already proficient, could help him in providing learning and teaching activities.[1] He said that by teaching religious knowledge to his children, they will believe that if this knowledge is ingrained in themselves and their souls then wherever they go and whatever the circumstances, they will still have a grip on life and have faith that was developed from an early age.[1] This resulted in Zakaria's children became fluent in Arabic and master in Ibn Aqil and Maqlub.[1] According to his eldest child, Nashruddin, Zakaria never forces his will on his children, such as when choosing a school he never forces his children to go to the school he wants, and leaves them free to make their own choices and does not like using his good name to get his children into a job, and wants them to always be independent and act according to procedures.[8] Even though they are given freedom, all of Zakaria's children have been taught religious knowledge so that no matter how much science they understand, they will be able to sort out what is good and what is bad because they already have a foundation of faith.[8] In raising his children, Zakaria never complained and carried out it as a person who never tires. According to his youngest son from first marriage, Syakrani, said that even though he is half his father's age, Zakaria's enthusiasm for work is higher than his own and sometimes it makes no sense to see this considering that Zakaria's physical condition has declined greatly.[1] Nashruddin later went to became Imam and Khatib for Friday Prayers replaced him, and his another son, Gamal, later became a teacher at MDTA Mahbatul Ulum during his holiday time from teaching at Sultan Syarif Kasim II State Islamic University.[1] While her daughter, Rita, also teaching on weekdays after returned from work at the Bengkalis District Health Department Office.[1] All of his children then got jobs according to their respective desires and abilities, and has also prepared them to replace him when he dies.[1] He was said to have succeeded in educating and directing his children well and feels happy and grateful.[1]

Bibliography

| Target/ Type | Title | Date | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Religious academic books | 1. Balqurramhi fi Sunniyyati Qunut Subhi | 1930 | [18][1] |

| 2. Masalah Usholli Dalam Sholat | 1932 | [19][1] | |

| 3. Rakaat Salat Sunah Tarawih | 1939 | [19][1] | |

| 4. Kumpulan Khutbah Jum'at dan Hari Raya Sebanyak Dua Belas Judul Khutbah | 1939 | [19][1] | |

| Kumpulan Muhadaroh Untuk Anak-anak Madrasah dalam Bidang Fiqih, Akhlak, Tauhid, dan sebagainya | Unknown | [1] | |

Death and legacy

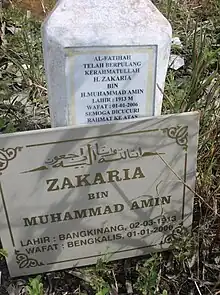

Zakaria died in Bengkalis, Riau, on 1 January 2006 at 06:30 WIB (UTC+07:00), at the age of 92, and was buried at Taman Makam Islam Harapan.[36] His obituary stated "Allahummaghfir lahu war hamhu wa 'afihi wa' fu'anhu, Amin" (English: O Allah, forgive him, give him mercy and peace and forgive him, Amen).[36] Several politicians paid tribute, including Bengkalis Regent, Syamsurizal, Deputy Regent, Normansyah Abdul Wahab, and Bengkalis Regional Secretary, Sulaiman.[37]

Zakaria was the subject of Profil Haji Zakaria Sebagai Pemuka Masyarakat Kecamatan Bengkalis, a thesis wrote by Sultan Syarif Kasim II State Islamic University student Azuwar Anuwar, which was based on an interview with him, his family, friends, and relatives from June until July 1991.[1][2] In 2023, he was the subject of Zakaria: Pahlawan Dalam Kenangan (literally Zakaria: a Hero in Memory), a documentary film which was based on footage from the thanksgiving ceremony for his award as a regional hero.

Honours

On 5 June 1980, Zakaria was awarded letter of appreciation from the Regional Qur'an Tilawatil Development Institute of Bengkalis Regency for his contribution in organizing the Musabaqah Tilawatil Qur'an selection between sub-districts in the Bengkalis Regency area at the Istiqomah Mosque in Bengkalis.[1] He received an award from Dharma Wanita in Bengkalis Regency on 22 January 1981 for his contribution to the Musabaqah Tilawatil Qur'an and Tambourine selection at the Bengkalis Regency level which took place from 20 until 22 January in Bengkalis.[1]

On 10 November 1990, Zakaria was awarded certificate and struggle medal for the class of 1945 by General Surono Reksodimedjo for his contribution, struggle, and devotion for Indonesian independence.[38] The award was given in order to celebrated 45 years of the founding of Indonesia.[38] Zakaria received the same award on 17 August 1995 in order to celebrated 50th years of Indonesia independence.[39]

In 2023, he along with twelve other people was posthumously named as a Regional Hero of Riau Province by Riau Regional People's Representative Council, in recognition of his contributions to the progress of Riau.[40] The award was received by his son, Gamal Abdul Nasir Zakaria.

National honours

- Award certificate and Medal of Struggle Level '45 from the National Daily Council (10 November 1990 and 17 August 1995)

- Regional Hero of Riau (9 August 2023)

Issue

| Name | Birth | Death | Marriage | Children | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Spouse | ||||

| Nashruddin Zakaria | 10 April 1934 | 1 January 1999 (aged 64) | Unknown | Nursiah | Syamsidar

Yusraini Muhammad Normayudin Erma Ernawati Hendrizon |

| Aminah Zakaria | 17 September 1938 | 15 July 2011 (aged 72) | Unknown | Rustam | Aprizami

Rudi Haryanto |

| Zaharah Zakaria | 1 February 1942 | 29 October 2007 (aged 65) | Unknown | Muhammad Yacub | Sri Mei Linda Andika

Sri Afrianti Wisra Okarianto Wiwik Siti Aisyah |

| Ulfah Zakaria | 14 April 1943 | — | Unknown | Diponegoro Dilapanga | Sutianingsih

Yusuf Aqil Siti Mariam |

| Azra'ie Zakaria | 31 July 1947 | 19 July 2019 (aged 71) | 1 December 1983 | Athiah Muhayat | Ilham Zurriyati Azra'ie

Maya Fadlilah Azra'ie Adri Imaduddin Azra'ie |

| Hanim Zakaria | 11 September 1950 | — | Unknown | Mokhtar | Tirta Mahdalena Mokhtar

Desy Ananda |

| Syakrani Zakaria | 23 November 1952 | — | Unknown | Rosnetti | Yudhi Andross

Elfikrie Andross Trio Andross Putri Rossya Ardelia Hasanah |

| Zulkarnain Zakaria | August 17, 1957 | — | Unknown | Mistiatiningsih | Muthia Vaora

Muhammad Zaqi Agil Nabila |

| Nukman Zakaria | 20 June 1960 | — | Unknown | Yuslina | Nurul Fitri Hidayah |

| Rinie Yuslina Fairuz Zakaria | 25 July 1964 | 14 March 2021 (aged 56) | 25 June 1990

Divorced 1 September 2020 |

Anton Budi Hartono Nasution | Latief Agam Hartono Nasution

Lizzy Paoly Hartono Nasution Melissa Alisya Hartono Nasution Susi Kartika Hartono Nasution Linda Claudia Hartono Nasution |

| Gamal Abdul Nasir Zakaria | 22 June 1965 | — | 13 March 2000 | Salwa Mahalle | Wafa Imani

Fawwaz Khalili Aisyah Syamila Umar Khalili |

| Rita Puspa Zakaria | 20 November 1967 | — | 28 January 2003 | Muhammad Yahman | Erin Kartika Puspa

Muhammad Asyrof Al-Ghifari Asy Syifa Kaila Saidah |

| Nida Suryani Zakaria | 15 April 1971 | — | 14 December 2016 | Khaidir Ahmad | — |

| Sri Purnama Zakaria | 20 October 1973 | — | 1 March 2009 | Amrizal | Amira Insyirah

Ammar Baihaqi |

Notes

- 1 2 3 According to an interview with Azuwar Anuwar on 15 June 1991, Zakaria stated that he cannot remember his birth date.[1][2] However, a document regarding the upgrading of mubalighs or preachers issued by the Governor of Riau Arifin Achmad in Pekanbaru on 20 August 1976 stated his date of birth as 7 March.[1]

Citations

- Saputra, Amrizal, Wira Sugiarto, Suyendri, Zulfan Ikhram, Khairil Anwar, M. Karya Mukhsin, Risman Hambali, Khoiri, Marzuli Ridwan Al-bantany, Zuriat Abdillah, Dede Satriani, Wan M. Fariq, Suwarto, Adi Sutrisno, Ahmad Fadhli (2020-10-15). PROFIL ULAMA KARISMATIK DI KABUPATEN BENGKALIS: MENELADANI SOSOK DAN PERJUANGAN (in Indonesian). CV. DOTPLUS Publisher. ISBN 978-623-94659-3-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Soelin, Emsjaf (1951-06-20). "ZAINAB, Bintang Harapan Panggung Sandiwara dari Ratu Asia". Aneka (in Indonesian).

- Pahlefi, Riza (2022-08-11). BENGKALIS: NEGERI JELAPANG PADI (in Indonesian). CV. DOTPLUS Publisher. ISBN 978-623-6428-59-7.

- Al-Bantany, Marzuli Ridwan (2021-09-04). SABDA PUJANGGA DARI NEGERI JUNJUNGAN (in Indonesian). CV. DOTPLUS Publisher. ISBN 978-623-6428-11-5.

- Nasution, Nasuha (2023-08-09). Ariestia (ed.). "Almarhum Tabrani Rab Hingga Maimanah Umar Terima Anugerah di HUT Riau". Tribunpekanbaru.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2023-08-10.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Anuwar, Azuwar (1991). "Profil Haji Zakaria Sebagai Pemuka Masyarakat Kecamatan Bengkalis". Sultan Syarif Kasim II State Islamic University (in Indonesian). Bengkalis.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Saputra 2020, p. 143.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Saputra 2020, p. 146.

- ↑ Tempo: Indonesia's Weekly News Magazine. (2007). Indonesia: Arsa Raya Perdana. p67

- ↑ Saputra 2020, p. 143–144.

- 1 2 3 Saputra 2020, p. 144.

- ↑ Saputra 2020, p. 144–145.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Saputra 2020, p. 145.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Saputra 2020, p. 147.

- ↑ Saputra 2020, p. 145, 147, 148.

- ↑ Saputra 2020, p. 147–148.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Saputra 2020, p. 148.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Saputra 2020, p. 149.

- 1 2 3 Pahlefi 2022, p. 158.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Saputra 2020, p. 150.

- 1 2 3 4 Pahlefi 2022, p. 135.

- 1 2 3 Pahlefi 2022, p. 134.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Saputra 2020, p. 152.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Saputra 2020, p. 153.

- ↑ Saputra 2020, p. 135.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Saputra 2020, p. 154.

- ↑ Saputra 2020, p. 150, 151.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Saputra 2020, p. 151.

- ↑ Saputra 2020, p. 154–155.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Saputra 2020, p. 155.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Saputra 2020, p. 156.

- ↑ Pahlefi 2022, p. 135, 187.

- 1 2 3 Pahlefi 2022, p. 187.

- 1 2 Pahlefi 2022, p. 188.

- ↑ Pahlefi 2022, p. 188, 189.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Saputra 2020, p. 157.

- ↑ Saputra 2020, p. 157–158.

- ↑ Saputra 2020, p. 146, 147.

- ↑ Soelin 1951.

- ↑ Al-Bantany 2021, p. 93–94.

- 1 2 Saputra 2020, p. 158.

- ↑ "Turut Berduka Cita Atas Berpulang Ke Rahmatullah Bpk. H. Zakaria". Pemerintah Daerah dan Masyarakat Kabupaten Bengkalis. 2006-01-01.

- 1 2 Surono (1990-11-10). "Piagam Penghargaan dan Medali Perjuangan Angkatan - 45". Dewan Harian Nasional Angkatan - 45 (in Indonesian).

- ↑ Surono (1995-08-17). "Piagam Penghargaan dan Medali Perjuangan Angkatan - 45". Dewan Harian Nasional Angkatan - 45 (in Indonesian).

- ↑ Nasution 2023.