| Part of Judaic series of articles on |

| Ritual purity in Judaism |

|---|

| |

In Jewish ritual law, a zavah (Hebrew זבה, lit. "one who[se body] flows") is a woman who has had vaginal blood discharges not during the usually anticipated menstrual cycle, and thus entered a state of ritual impurity. The equivalent impurity that can be contracted by males, by experiencing an abnormal discharge from their genitals, is known as the impurity of a zav.

In the realm of tumah and taharah, the zavah, just like a niddah (menstruant woman) and yoledet (woman after giving birth), is in a state of major impurity, and creates a midras by sitting and by other activities (Leviticus 15:4, 15:9, 15:26). Another aspect of her major impurity, is that a man who conducts sexual intercourse with her becomes unclean for a seven-day period. Additionally, the zavah and her partner are liable to kareth (extirpation) for willfully engaging in forbidden sexual intercourse, as is the case for a niddah and yoledet.

Hebrew Bible

Torah sources for the zavah are sourced in the book of Leviticus (Leviticus 15:1–15, Leviticus 15:25–33).

According to textual scholars, the regulations concerning childbirth,(Leviticus 12) which have a similar seven-day waiting period before washing, and the sin and whole offerings, were originally suffixed to those concerning menstruation, but were later moved.[1]

In rabbinic literature

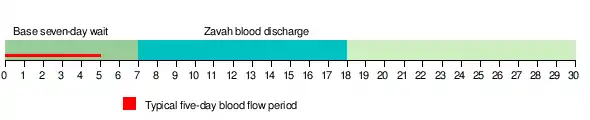

According to the Jerusalem Talmud, the eleven-day period between each [monthly] menstrual cycle is Halakha LeMoshe MiSinai.[2] This has been explained by Maimonides[3] to mean that seven days are given to all women during their regular monthly menstrual cycle, known as the days of the menstruate (Hebrew: niddah), even if her actual period lasted only 3 to 5 days. From the eighth day after the beginning of her period (the terminus post quem, or the earliest date in which they begin to reckon the case of a zavah), when she should have normally concluded her period, these are days that are known in Hebrew as the days of a running issue (Hebrew: zivah), and which simply defines a time (from the 8th to the 18th day, for a total of eleven days) that, if the woman had an irregular flow of blood for three consecutive days during this time, she becomes a zavah gedolah and is capable of defiling whatever she touches, and especially whatever object she happens to be standing upon, lying upon or sitting upon. If blood flows or issues during that short window when it is expected not to, that, then, is an irregular flow.[4] Only in such cases of irregular sightings of blood would the woman require seven days of cleanness before she can be purified, according to the Written Law of Moses (Leviticus 15:25–28).

Although the Written Law explicitly enjoins women to count seven days of cleanness when they have seen irregular blood sightings (the irregularity occurring only from the eighth day of the start of her regular period and ending with the conclusion of the eighteenth day), the Sages of Israel have required all women who have experienced even their regular and natural purgation to count seven days of cleanness before they can be purified.[5]

Zavah ketanah

The woman, within an eleven-day window of the completion of her base seven-day niddah period (and her typical immersion in the mikveh) notices an abnormal blood discharge. This one time discharge deems her a zavah ketanah (minor zavah) and brings the requirement for her to verify that the next day will show no discharge. Provided the next day is clean, her immersion in the mikveh prior to sunset makes her tahor (pure) after sunset.

Zavah gedolah

In the zavah gedolah (major zavah) scenario, the woman, within an eleven-day window of the completion of her base seven-day niddah period (and immersion in the mikveh) notices an abnormal blood discharge.[6] If the next day another discharge is noticed, followed by yet another discharge on the third consecutive day, she is deemed a zavah gedolah. She is then required to count seven clean days, immerse in a mikveh on the seventh day and bring a korban on the eighth.

Other laws

According to the Talmud, the law of zavah gedolah is applicable if the discharge in question happens for a minimum of three consecutive days[7]

A female must be at least ten days old to be eligible for zavah gedolah status.[8] this is possible only in a case wher the newborn experienced a uterine discharge of blood on the day of her birth, and again on the 8th 9th and 10th day consecutively[9]

The Tosefta[10] stipulates that unlike a zav, who is required to immerse in a spring (as opposed to the standard mikveh bath) to obtain taharah, a zavah may complete her purification process by immersing in a either a mikveh or a spring. This is the halakhic position accepted by virtually all Orthodox authorities.[11]

The zavah is commonly known as one of four types of tumah that are required to bring a sacrifice post the purification process.[12] The korban consists of both a sin offering and a whole offering, each involving a dove.

Viewed as Divine punishment

Obadiah ben Jacob Sforno reasons that the zavah gedolah state is a divine consequence to alert the woman from acting in a manner comparative to Chava (Eve). This unpleasant consequence is implied by God's message to Chava in the verse "I will increase and multiply your discomfort" (Genesis 3:16), with the seven-day waiting period intended to allow a spirit of repentance and purity to enter her will. Her bringing of a dual sacrifice, the Chatat and Olah, are to rectify her negative action and thought, respectively.[13]

Targum Yonathan describes the zavah state as a divine consequence to a woman who neglects the requirement to take adequate precautions involving the laws and nuances of menstrual impurity.[14]

In modern Judaism

Due to the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem, Judaism regards the sacrificial regulations as being in abeyance; rabbinical tradition subsequently differentiated less between the regulations of zavah and those for niddah.

In Orthodox Judaism nowadays, zavah (an abnormal discharge) and niddah (healthy menstruation) are no longer distinguished. A menstruating woman (niddah) is required to wait the seven additional clean days that she would if she were a zavah.

Conversely, Reform Judaism regards such regulations as anachronistic; adherents of Conservative Judaism take a view somewhere between these views, with opinions in favor of returning to the Biblical distinction between niddah (ending seven days from the beginning of a normal menstrual period) and zavah (ending seven days after the end of an abnormal discharge).

See also

References

- ↑ Jewish Encyclopedia, Leviticus

- ↑ Jerusalem Talmud (Berakhoth 37a [5:1])

- ↑ Maimonides, Mishne Torah (Hil. Issurei Bi'ah 6:1–5)

- ↑ Rabbi Avram Reisner (2006), Observing Niddah in Our Day, Committee on Jewish Law and Standards, Rabbinical Assembly, p. 9

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud (Berakhot 31a, Rashi s.v. יושבת עליה ז' נקיים)

- ↑ This one time discharge deems her a zavah ztanah (minor zavah) and brings the requirement for her to verify that the next day will show no discharge

- ↑ Bava kama, 24 a.

- ↑ Sifra to Leviticus 15:19

- ↑ Rashi on niddah, 32b.

- ↑ Megillah, ch 1: 14.

- ↑ Hilchot haRif, Shevu'ot 5a.

- ↑ Rashi on Makkoth 8b

- ↑ Sforno to Vayikra 15:19

- ↑ Targum Jonathan on Ecclesiastes 10:18