| Zhao dynasty/Triệu dynasty | |

|---|---|

| Country | Nanyue |

| Founded | 204 BC |

| Founder | Zhao Tuo |

| Final ruler | Zhao Jiande |

| Titles | King of Nanyue |

| Estate(s) | Panyu |

| Deposition | 111 BC |

| Part of a series on the |

| History of China |

|---|

| History of Vietnam |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

The Triệu dynasty or Zhao dynasty (Chinese: 趙朝; lit. 'Zhao dynasty'; Vietnamese: Nhà Triệu; 茹趙) ruled the kingdom of Nanyue, which consisted of parts of southern China as well as northern Vietnam. Its capital was Panyu, in modern Guangzhou. The founder of the dynasty, Zhao Tuo (Triệu Đà), was a Chinese general[1][2] from Hebei and originally served as a military governor under the Qin dynasty.[3] He asserted the state's independence in 207 BC as the Qin dynasty was collapsing.[4] The ruling elite included both native Yue and immigrant Han peoples.[5] Zhao Tuo conquered the Vietnamese state of Âu Lạc and led a coalition of Yuè states in a war against the Han dynasty, which had been expanding southward. Subsequent rulers were less successful in asserting their independence and the Han dynasty finally conquered the kingdom in 111 BC.

Historiography

The scholar Huang Zuo produced the first detailed published history of Nanyue in the fifteenth century.[6] Chinese historians have generally denounced Nanyue as separatists from the Han dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD), but have also praised them as a civilizing force. A particularly strident denunciation was produced by poet Qu Dajun in 1696.[7] Qu praised Qin Shi Huang as a model of how to uphold the purity of Chinese culture, and compared Zhao Tuo unfavorably to the emperor.[7] A more positive view of Nanyue multiculturalism was presented by Liang Tingnan in Nányuè Wŭ Zhǔ Zhuàn (南越五主傳; "Biographies of the Five Lords of Nanyue") in 1833.[6] Cantonese refer to themselves as Yuht, the Cantonese pronunciation of Yuè/Việt.[8] In modern times, the character 粵 (yuè) refers to Cantonese while 越 (yuè) refers to Vietnamese. But historically, these two characters were interchangeable.[9]

Meanwhile, Vietnamese historians have struggled with the issue of whether to regard the Triệu dynasty heroically as founders of Vietnam, or to denounce them as foreign invaders. For centuries afterward, Zhao Tuo was a folk hero among the Viets, and was remembered for standing up to the Han Empire.[10] After Lý Bí drove the Chinese out of northern Vietnam, he proclaimed himself "Emperor of Nam Việt" (Nam Việt đế; 南越帝) in 544, thus identifying his state as a revival of the Nanyue, despite obvious differences in terms of location and ethnic makeup.[11] In the thirteenth century, Lê Văn Hưu wrote a history of Vietnam that used the Triệu dynasty as its starting point, with Zhao Tuo receiving glowing praise as Vietnam's first emperor.[6] In the 18th century, Ngô Thì Sĩ reevaluated Zhao Tuo as a foreign invader.[6] Under the Nguyễn dynasty, Zhao Tuo continued to receive high praise, although it was acknowledged that the original Nanyue was not in fact a Vietnamese state.[6] The current government of Vietnam portrays Zhao Tuo negatively as a foreign invader who vanquished Vietnam's heroic King An Dương despite there being a campaign to reconsider the role of Zhao Tuo due to rising tensions between Vietnam and China.[6] Modern Vietnamese are descended from the ancient Yue of northern Vietnam and western Guangdong, according to Peter Bellwood.[12]

History

Zhao Tuo

Zhao Tuo (r. 204–136 BC), also called Triệu Đà, the founder of the dynasty, was an ethnic Chinese born in the State of Zhao, now Hebei province. He became military governor of Nanhai (now Guangdong) upon the death of Governor Ren Xiao in 208 BC, just as the Qin dynasty was collapsing. The Qin governor of Canton advised Zhao to found his own independent kingdom since the area was remote and there were many Chinese settlers in the area.[13] He asserted Nanhai's independence declared himself the king of Nam Việt in 204 BC, established in the area of Lingnan, the modern provinces of comprises Guangdong, Guangxi, south Hunan, south Jiangxi and other nearby areas.[14] He ruled Nanyue and committed acts of defiance against Emperor Gaozu of Han and he severed all ties with the Han dynasty, killed many Han employees appointed by the central government and favored local customs.[14] Being a talented general and cunning diplomat, he sought a peaceful relationship with both the Qin dynasty and the succeeding Han dynasty.

In 196 BC, the Emperor Gaozu of Han sent the scholar Lu Jia to the court of Zhao Tuo.[15] On this occasion, Zhao Tuo squatted and wore his hair in a bun, in the Yuè manner.[15] "You are a Chinese and your forefathers and kin lie buried in Zhending in the land of Zhao", Lu told the king.[16] "Yet now you turn against that nature which heaven has given you at birth, cast aside the dress of your native land and, with this tiny, far-off land of Yue, think to set yourself up as a rival to the Son of Heaven and an enemy state....It is proper under such circumstances that you should advance as far as the suburbs to greet me and bow to the north and refer to yourself as a 'subject'."[16] After Lu threatened a Han military attack on Nanyue, Zhao Tuo stood up and apologized.[16] Lu stayed at Panyu for several months and Zhao Tuo delighted in his company.[17] "There is no one in all Yue worth talking to", said the king, "Now that you have come, everyday I hear something I have never heard before!"[17] Lu recognized Zhao Tuo as "King of Yue".[17] An agreement was reached that allowed legal trade between the Han dynasty and Nanyue, as the people of Nanyue were anxious to purchase iron vessels from the Han dynasty.[18] When Lu returned to Chang'an, the Emperor Gaozu of Han was much pleased by this result.[17]

Lü Zhi, the Han empress dowager, banned trade with Nanyue in 185 BC.[18] "Emperor Gaozu set me up as a feudal lord and sent his envoy giving me permission to carry on trade," said Zhao Tuo.[18] "But now Empress Lü...[is] treating me like one of the barbarians and breaking off our trade in iron vessels and goods."[18] Zhao Tuo responded by declaring himself an emperor and by attacking some border towns.[18] His imperial status was recognized by the Minyue, Western Ou (Âu Việt), and the Luolou.[19] The army sent against Nanyue by Empress Lü was ravaged by a cholera epidemic.[15] When Zhao Tuo was reconciled with the Han Empire in 180 BC, he sent a message to the Emperor Wu of Han in which he described himself as, "Your aged subject Tuo, a barbarian chief".[19] Zhao Tuo agreed to recognize the Han ruler as the only emperor.[19]

Peace meant that Nanyue lost its imperial authority over the other Yue states. Its earlier empire had not been based on supremacy, but was instead a framework for a wartime military alliance opposed to the Han.[15] The army Zhao Tuo had created to oppose the Han was now available to deploy against the Âu Lạc kingdom in modern-day northern Vietnam.[15] This kingdom was conquered in 179–180 BC.[15] Zhao Tuo divided his kingdom into two regions: Cửu Chân and Giao Chỉ. Giao Chỉ now encompasses most of northern Vietnam. He allowed each region to have representatives to the central government, thus his administration was quite relaxed and had a feeling of being decentralized. However, he remained in control. By the time Zhao Tuo died in 136 BC, he had ruled for more than 70 years and outlived his sons.

In modern Vietnam, Zhao Tuo is best remembered as a character in the "Legend of the Magic Crossbow". According to this legend, Zhao Tuo's son Trong Thủy married Mỵ Châu, the daughter of King An Dương of Âu Lạc, and used her love to steal the secret of An Dương's magic crossbow.[21]

Zhao Mo

Zhao Tuo died in 136 BC and was succeeded by his grandson Zhao Mo (Chinese: 趙眜; pinyin: Zhào Mò; Vietnamese: Triệu Mạt). He was 71 years old at the time of ascending to the throne. In 135 BC, the Minyue attacked and Zhao Mo requested the assistance of the Han Empire.[22] The Emperor Wu of Han offered to "help" by sending his army, ostensibly to suppress the assist Nanyue, but with an eye of seizing the country should an occasion arise. Crown Prince Zhao Yingqi was sent to live and study in the Han court.[22] Zhao Mo took this as a gesture of goodwill by the Emperor Wu of Han, whom he viewed as a brother, to strengthen the relationship between Han and Nanyue. Zhao Mo died in 124 BC. His mausoleum was found in Guangzhou in 1983.

Zhao Yingqi

Zhao Yingqi (Chinese: 趙嬰齊; pinyin: Zhào Yīngqí, Vietnamese: Triệu Anh Tề, r. 124–112 BC) was the crown prince when his father, Zhao Mo, died. Zhao Yingqi's appointment to kingship was a conciliatory measure to the Han emperor in Chang'an as a sign of respect. This crowned prince, Zhao Yingqi, lived most of his life in the Han dynasty where he had fathered a son by an ethnic Chinese woman surnamed Jiu (Chinese: 樛; pinyin: Jiū); In one popular theory, she was Emperor Wu's own daughter. He named the son Zhao Xing. Only when his father, Zhao Mo, died did Zhao Yingqi receive permission to go home for his father's funeral. This happened in 124 BC. Zhao Yingqi then ascended the throne of Nanyue. Not much is known about Zhao Yingqi's reign, probably because it is a short one and he was subservient to the Han emperor. His son, Zhao Xing, was only about 6 years old when he died. Owing to Zhao Xing's extreme youth, his mother Lady Jiu, became the Empress Dowager.

Zhao Yingqi's death precipitated the events that would lead to the seizure and domination of Nanyue by the Han forces.

Zhao Xing

Zhao Xing (r. 113–112 BC), also called Triệu Hưng, was just 6 years old when he ascended the throne. Soon thereafter, Emperor Wu of Han summoned him and his mother, Lady Jiu, to an audience to pay homage in the Han court. The Han dynasty held Lady Jiu and Zhao Xing under the pretext that the young king needed their protection. By acquiescing to this gesture, both the empress dowager and the young emperor gave the public the impression that they were just puppets in the hands of the Han court.

With Zhao Xing in their hands and the queen dowager beheaded, the Han dynasty prepared their army for an invasion. In 112 BC, the emperor sent two of his commanders, Lu Bode and Yang Pu, along with 5,000 of his best soldiers to invade Nanyue.

Zhao Jiande

Nanyue's senior prime minister, Quan Thai-pho, Lü Jia sent out the army to meet the Han at the border to repel the invasion. The army was strong, but smaller in number. Meanwhile, inside the country, the word has spread that Zhao Xing was in the hand of the Han dynasty. The Nanyue feared that if they resist, their king would be harmed by the Han dynasty. The country was now in a state of chaos. When the Han kept sending more and more reinforcements for his army at the border, the Nanyue's army was unable to hold their position. Lü Jia saw that Nanyue must have a new king in order to calm its people and to stir up Nanyue patriotism to fight. Zhao Jiande (also called Triệu Kiến Đức), Zhao Yingqi's eldest son from one of his concubines, took the burden of leading his people to war.

Decline of the dynasty

Emperor Wu of Han dispatched soldiers against Nanyue.[23] With its king being too young and inexperienced and leading an untrained, however brave army, Nanyue was only able to keep their stronghold for a while. Han crushed the Nanyue army along with Lü Jia and his King (Zhao Jiande), both resisted until the end. Based on many temples of Lü Jia, his wives and soldiers scattering in Red River Delta of modern-day northern Vietnam, the war might last until 98 BC.[24][25]

After the fall of Panyu, Tây Vu Vương (the captain of Tây Vu area of which the center is Cổ Loa) revolted against the First Chinese domination from Western Han dynasty.[26] He was killed by his assistant Hoàng Đồng (黄同).[27][28]

Afterwards, Nanyue territory was divided into nine districts and incorporated into the Han dynasty as the prefecture of Jiaozhi (Giao Chỉ). Han dynasty would dominate Jiaozhi until the revolt of the Trưng Sisters, who led a revolt in AD 40.[29]

List of monarchs

| Posthumous name | Given name | Reign | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | Pinyin | Vietnamese | Chinese | Pinyin | Vietnamese | |

| 武帝 | Wǔ Dì | Vũ Đế | 趙佗 | Zhào Tuó | Triệu Đà | 203–137 BC |

| 文帝 | Wén Dì | Văn Đế | 趙眜 | Zhào Mò | Triệu Mạt | 137–122 BC |

| 明王 | Míng Wáng | Minh Vương | 趙嬰齊 | Zhào Yīngqí | Triệu Anh Tề | 122–115 BC |

| 哀王 | Āi Wáng | Ai Vương | 趙興 | Zhào Xīng | Triệu Hưng | 115–112 BC |

| 術陽王 | Shù Yáng Wáng | Thuật Dương Vương | 趙建德 | Zhào Jiàndé | Triệu Kiến Đức | 112–111 BC |

Nanyue culture

There was a fusion of the Han and Yue cultures in significant ways, as shown by the artifacts unearthed by archaeologists from the tomb of Nanyue in Guangzhou. The Nanyue tomb in Guangzhou is extremely rich. There are quite a number of bronzes that show cultural influences from the Han, Chu, Yue and Ordos regions.[30]

Gallery

.JPG.webp) State of King Zhao Tuo (Triệu Đà)

State of King Zhao Tuo (Triệu Đà) Bronze wine vessel

Bronze wine vessel Đông Sơn bronze drum

Đông Sơn bronze drum Bronze disk

Bronze disk Bronze house model

Bronze house model Mausoleum of King Triệu Mạt (Zhao Mo)

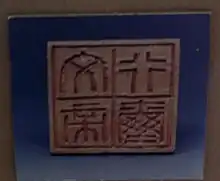

Mausoleum of King Triệu Mạt (Zhao Mo) Gold seal

Gold seal Jiaoxing yubei

Jiaoxing yubei Chengpan gaozu bei

Chengpan gaozu bei Jade burial suit of King Zhao Mo (Triệu Mạt)

Jade burial suit of King Zhao Mo (Triệu Mạt) Đông Sơn bronze jar

Đông Sơn bronze jar Bronze mortar and pestle

Bronze mortar and pestle Bronze mirror inlaid with silver

Bronze mirror inlaid with silver Game of Liubo

Game of Liubo Game of Liubo

Game of Liubo Armour with reconstructed replica

Armour with reconstructed replica.jpg.webp) Tomb of Prime minister Lü Jia (Lữ Gia) and General Nguyễn Danh Lang

Tomb of Prime minister Lü Jia (Lữ Gia) and General Nguyễn Danh Lang

See also

Citations

- ↑ Wicks, Robert (2018). Money, Markets, and Trade in Early Southeast Asia: The Development of Indigenous Monetary Systems to AD 1400. p. 27. ISBN 9781501719479.

- ↑ Walker, Hugh (2012). East Asia: A New History. p. 107. ISBN 9781477265178.

- ↑ Patricia M. Pelley Postcolonial Vietnam: New Histories of the National Past 2002 Page 177 "The fact that he was Chinese was irrelevant; what mattered was that Triệu Đà had declared the independence of Vietnam."

- ↑ Bodde, p. 84.

- ↑ Snow, Donald B., Cantonese as written language: the growth of a written Chinese vernacular (2004), Hong Kong University Press, p. 70.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Yoshikai Masato, "Ancient Nam Viet in historical descriptions", Southeast Asia: a historical encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor, Volume 2, ABC-CLIO, 2004, p. 934.

- 1 2 Shmuel Noah Eisenstadt, Wolfgang Schluchter, Björn Wittrock, Public spheres and collective identities, Transaction Publishers, 2001, p. 213.

- ↑ Caihua Guan, English-Cantonese Dictionary: Cantonese in Yale Romanization, New Asia – Yale-in-China Chinese Language Center, p. 57, 2000. "Cantonese N....Yuhtyúh (M: geui)".

Ramsey, S. Robert, The Languages of China, 1987, p. 98. "Named after an ancient 'barbarian' state located in the Deep South, the Yue [Cantonese] are true Southerners.

Constable, Nicole, Guest People: Hakka Identity in China and Abroad (2005) - ↑ Hashimoto, Oi-kan Yue, Studies in Yue Dialects 1: Phonology of Cantonese, 1972, p. 1. See also "百粤", YellowBridge.

- ↑ Woods, L. Shelton (2002). Vietnam: a global studies handbook. ABC-CLIO. p. 15. ISBN 9781576074169.

- ↑ Anderson, James (2007). The rebel den of Nùng Trí Cao: loyalty and identity along the Sino-Vietnamese frontier. NUS Press. p. 36. ISBN 9789971693671.

- ↑ Peter Bellwood. "Indo-Pacific prehistory: the Chiang Mai papers. Volume 2". Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association of Australian National University: 96.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Taylor (1983), p. 23

- 1 2 Chapius, Oscar, A history of Vietnam: from Hong Bang to Tu Duc

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Taylor, Keith Weller, The Birth of Vietnam, p. 24. University of California Press, 1991.

- 1 2 3 Sima Qian, Burton Watson, Records of the Grand Historian: Han Dynasty I, pp 224–225. ISBN 0-231-08165-0.

- 1 2 3 4 Sima Qian, p, 226.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wicks, Robert S., Money, markets, and trade in early Southeast Asia: the development of indigenous monetary systems to AD 1400, SEAP Publications, 1992. p. 27.

- 1 2 3 Wicks, p. 28.

- ↑ Hansen, Valerie (2000). The Open Empire: A History of China to 1600. New York, USA & London, UK: W.W. Norton & Company. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-393-97374-7.

- ↑ Sachs, Dana, Two cakes fit for a king: folktales from Vietnam, pp. 19–26. University of Hawaii Press, 2003.

- 1 2 Taylor, p. 27.

- ↑ Yu, Yingshi (1986). Denis Twitchett; Michael Loewe (eds.). Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220. University of Cambridge Press. p. 453. ISBN 978-0-5212-4327-8.

- ↑ "Lễ hội chọi trâu xã Hải Lựu (16–17 tháng Giêng hằng năm) Phần I (tiep theo)". 2010-02-03.

Theo nhiều thư tịch cổ và các công trình nghiên cứu, sưu tầm của nhiều nhà khoa học nổi tiếng trong nước, cùng với sự truyền lại của nhân dân từ đời này sang đời khác, của các cụ cao tuổi ở Bạch Lưu, Hải Lựu và các xã lân cận thì vào cuối thế kỷ thứ II trước công nguyên, nhà Hán tấn công nước Nam Việt của Triệu Đề, triều đình nhà Triệu tan rã lúc bấy giờ thừa tướng Lữ Gia, một tướng tài của triều đình đã rút khỏi kinh đô Phiên Ngung (thuộc Quảng Đông – Trung Quốc ngày nay). Về đóng ở núi Long Động – Lập Thạch, chống lại quân Hán do Lộ Bác Đức chỉ huy hơn 10 năm (từ 111- 98 TCN), suốt thời gian đó Ông cùng các thổ hào và nhân dân đánh theo quân nhà Hán thất điên bát đảo."

- ↑ "List of temples related to Triệu dynasty and Nam Việt kingdom in modern Vietnam and China". 2014-01-28.

- ↑ Từ điển bách khoa quân sự Việt Nam, 2004, p564 "KHỞI NGHĨA TÂY VU VƯƠNG (lll TCN), khởi nghĩa của người Việt ở Giao Chỉ chống ách đô hộ của nhà Triệu (TQ). Khoảng cuối lll TCN, nhân lúc nhà Triệu suy yếu, bị nhà Tây Hán (TQ) thôn tính, một thủ lĩnh người Việt (gọi là Tây Vu Vương, "

- ↑ Viet Nam Social Sciences vol.1–6, p91, 2003 "In 111 B.C. there prevailed a historical personage of the name of Tay Vu Vuong who took advantage of troubles circumstances in the early period of Chinese domination to raise his power, and finally was killed by his general assistant, Hoang Dong. Professor Tran Quoc Vuong saw in him the Tay Vu chief having in hands tens of thousands of households, governing thousands miles of land and establishing his center in Co Loa area (59.239). Tay Vu and Tay Au is in fact the same.

- ↑ Book of Han, Vol. 95, Story of Xi Nan Yi Liang Yue Zhao Xian, wrote: "故甌駱將左黃同斬西于王,封爲下鄜侯"

- ↑ Gernet, Jacques (1996). A History of Chinese Civilization. Cambridge University Press. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-521-49781-7.

- ↑ Guangzhou Xi Han Nanyue wang mu bo wu guan, Peter Y. K. Lam, Chinese University of Hong Kong. Art Gallery – 1991 – 303 pages – Snippet view

References

- Bodde, Derk (1986). "The State and Empire of Ch'in". In Twitchett, Denis; Loewe, Michael (eds.). The Cambridge History of China, Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- Taylor, Keith Weller. (1983). The Birth of Vietnam (illustrated, reprint ed.). University of California Press. ISBN 0520074173. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

- Viet Nam Su Luoc by Trần Trọng Kim

- Viet Su Toan Thu by Pham Van Son