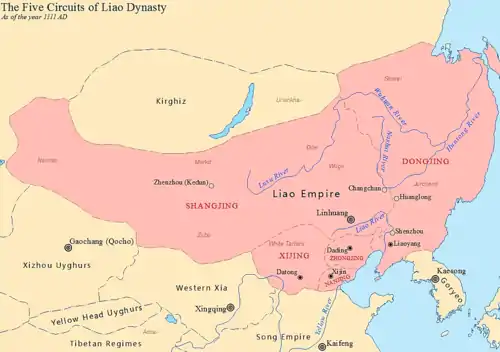

The Liao dynasty was a Khitan-led imperial dynasty of China. This article discusses the provincial system that existed within the Liao dynasty from the early 10th century until the fall of the empire in 1125, in what is now North China, Northeast China and Mongolia.

Overview

The expansion of the Liao dynasty in the 10th century eventually necessitated some sort of administrative division. During the reign of the first Liao emperor Taizu, he informally divided his lands into a northern region and a southern region; the third emperor, Shizong, formalized this arrangement in 947.[1] The northern section was mostly (but not entirely) inhabited by the Khitan and other nomadic tribes, while the southern half was largely inhabited by sedentary peoples, such as Han Chinese and Po-hai. Each region had its own capital and its own system of law. The northern region was originally governed mostly through a traditional Khitan system of tribal government, but a second system was set in place[2] that dealt with sedentary people living within its borders. The government of the southern region, in contrast, adopted many Chinese institutions and legal systems.

As time went on and the Liao consolidated their hold over their sedentary possessions, the southern region was eventually split into four provinces (called circuits).[3] This meant that, by the middle of the 11th century, the Liao Empire was divided into a total of five circuits. The names of their capitals are listed below:

| Capitals/Ancient name | Prefectures level | Modern location | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Westernized | Chinese | Westernized | Chinese | |

| Shangjing "Upper (Northern, Supreme) Capital" |

上京 | Linhuang | 臨潢 | Bairin Left Banner (巴林左旗) Inner Mongolia |

| Zhongjing "Central Capital" |

中京 | Dading | 大定 | near Ningcheng (寧城) Inner Mongolia |

| Dongjing "Eastern Capital" |

東京 | Liaoyang | 遼陽 | Liaoyang (遼陽) Liaoning |

| Xijing "Western Capital" |

西京 | Datong | 大同 | Datong (大同) Shanxi |

| Nanjing "Southern Capital" |

南京 | Xijinfu | 析津 | Beijing (北京) |

The high-ranking officials of each circuit would travel to the emperor's camp twice a year and discuss matters of the state. Each capital, except for the Supreme Capital, was governed by a regent, who was normally a member of the imperial family.[4] The governors of the southern provinces enjoyed a degree of power but were still under the firm control of the emperor and his advisers, who were mainly from the Northern Region. In addition, the southern governors were barred from having any effective command over the military; the emperor and his court were careful to reserve this power for themselves.[5]

Below the regents, government officers tended to be of the same ethnic background as the populations they ruled over; generally speaking, officials in the north were largely Khitan, while those in the south were not.[6] Although there were several exceptions, circuits were usually subdivided into prefectures, which were then themselves subdivided into counties ruled by magistrates. The powers of the prefects and magistrates varied depending on the region and time period; in several situations some of their functions were assumed by officials of the circuit level or the central government. In general, however, prefects were responsible for the collection of taxes and management of regionally stationed military forces, while magistrates dealt with village leaders and made sure the laws of the government were being carried out on a local basis.[7]

Circuits

Northern Region

This region was the largest geographically within the Liao state, and also contained the area the Khitan lived in prior to the foundation of the Liao dynasty. It was home to a large number of nomadic tribes that were under varying degrees of control, and also contained some sedentary settlements.

The tribal system that governed the various nomad clans who considered themselves to be a part of the Liao state was very convoluted and relied more on personal relationships than any formalized system.[8] In general, the more proximate a tribe was located relative to the center of the empire and the more its members had personal dealings with the emperor, the more loyal it was. At the opposite end of the spectrum, tribal confederations such as the Zubu or Tsu-Pu who were on the distant fringes of the empire tended to be significantly less reliable and more hostile to Khitan activity in their areas; frequent military expeditions were required to keep them in line.[9]

The Northern Region was home to a Supreme Capital, which was decently sized. The emperor and his advisers, however, rarely spent significant time there; they would instead spend most of the year traveling through the northern region and meeting with individual tribes and their leaders, who expected the emperor to personally make decisions regarding matters of law and justice.[8]

While the Northern Region retained its tribal character for the entire history of the Liao Empire, there was a gradual importation of governmental and economic customs taken from Chinese and other sedentary populations into the area. In 983 the legal code of the Tang dynasty, already in use in the Southern Capital, was translated into the Khitan language so it could be adopted by officials in the North. Further reforms followed, to the chagrin of Khitan tribal members.[10]

During the 1114-1125 war with the Jurchen that resulted in the destruction of the Liao state, the Jurchen leader Aguda decided to seize the Supreme Capital, not so much because it held any strategic importance as that it would be useful for symbolic purposes. This was accomplished in 1120; Jurchen troops looted and burned down buildings and tombs of the imperial family.[11] Aguda's Jin Empire, however, never managed to subordinate the bulk of the various Mongol and Turkic tribes that had previously pledged allegiance to the Liao; these tribes remained largely independent until the formation of the Mongol Empire at the beginning of the 13th century.

Southern Region

The original Southern Region, formed by the split of the Liao Empire into two administrative divisions, is discussed above. It was eventually split into multiple provinces, one of which was a "new" Southern Region, with a capital at modern-day Beijing.

The Southern Circuit largely formed out of a portion of the Sixteen Prefectures that had been ceded to the Liao Empire by Emperor Gao Zu of the Later Jin dynasty in 937.[12] Over the course of the next several centuries the Song Empire continually claimed a right to this province but despite military efforts it was retained by the Liao. Due to its wealth it was at times taxed more heavily than other provinces. The region was suitable for growing rice, but the central government repeatedly banned the growing of paddy fields, likely out of a fear that the fields and the canals needed to sustain them would hinder the effectiveness of the Khitan cavalry.[13]

During the Jurchen invasion the Southern Region held out until 1122, under the banner of a separatist government. A Song attempt to seize the province having failed that year, Aguda invaded and captured the Southern capital without much difficulty.[14]

Eastern Region

The Eastern Circuit consisted of the bulk of the old Kingdom of Balhae, which had originally survived within the Liao empire as a vassal state under the rule of a member of the imperial family.[15] The capital of the original Southern Region had been located here; after the Southern Region was split the city instead became the capital of the Eastern Region and was named Dongjing.[16] It bordered both the Kingdom of Goryeo and the Jurchen tribes, and as a result it contained a series of frontier stations and trading posts.[17]

As a result of its proximity to the Jurchen, it was the first Liao province to fall before them when they declared war. Having begun to attack border stations in 1114, they had largely completed their conquest of the Eastern Region by 1118.[18]

Central Region

The Central Circuit was composed of the former territories of the Hsi, a people who, like the Balhae, had been allowed to retain a degree of autonomy after their conquest by the Khitan. Administratively this area fell under the Southern Region. Toward the end of the 10th century the central government enacted a series of measures that largely ended the Hsi's special status and fully incorporated the region into the empire. In 1006 the former residence of the Hsi king was declared to be the site of a new Central capital, which was walled in the following year. Chinese settlers moved into the capital[19] and the surrounding lands, which were suitable for farming. Unlike the other capital cities, however, the Central capital never evolved into a large city, maintaining only a small population of Chinese and Hsi citizens.[20]

The Central Region was lost in the first month of 1122. Aguda had sent a Jurchen army under the command of a Liao defector toward the end of 1121, and during a winter campaign it seized the capital and surrounding area.[21]

Western Region

The Western Circuit was the final province created within the Liao state. In 1044 the modern-day city of Datong was declared to be a capital of an area consisting of parts of the conquered Sixteen Prefectures and the Yinshan Mountain region. Prior to this, it had been a part of the Southern Circuit. A large Chinese population was located within this region.[22]

During the war with the Jurchen the Liao emperor Tianzuo had retreated to the Yinshan region, which served as an effective move; although the Jurchen took the Western Capital in that same year they were unable to root out Tianzuo's remaining forces. It was only after Tianzuo left this area and attempted to recapture the Southern Capital that the Jurchen were finally able to defeat and capture him.[23]

Before Tianzuo launched his ill-fated offensive, a member of the royal family, Yelü Dashi, advised him not carry out the expedition. Upon Tianzuo's refusal, Dashi abandoned the emperor's camp and fled northward. From there he was able to eventually set up his own domain and expand west, forming the successor state known as the Qara Khitai or Western Liao.[24]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Twitchett and Tietze, p. 77

- ↑ Hucker, p. 54

- ↑ Wittfogel and Chia-sheng, p. 37

- ↑ Hucker, p. 53

- ↑ Twitchett and Tietze, p. 80

- ↑ Wittfogel and Chia-sheng, p. 446, states that most southern officials were Chinese. For an overview of the government offices that existed in both the northern and southern regions of the Liao empire, see Hucker, pp. 53-5

- ↑ Wittfogel and Chia-sheng, pp. 448-9

- 1 2 Twitchett and Tietze, pp. 79-80; Mote, p. 89

- ↑ Mote, pp. 59-60

- ↑ Twitchett and Tietze, pp. 93-4. On the other hand, ethnic Chinese that were subject to traditional Khitan law were known to complain about its relative harshness; see Mote, p. 74

- ↑ Twitchett and Tietze, p. 146

- ↑ Twitchett and Tietze, p. 79; Mote, p. 65

- ↑ Twitchett and Tietze, pp. 94-6

- ↑ For details of the opposition government and the fall of the Southern Circuit to Aguda, see Biran, pp. 20-23

- ↑ Twitchett and Tietze, p. 66. Prince Bei was made ruler in this state after his father Abaoji realized that Bei would likely be unable to enforce his claims as successor to the imperial title after his death. After Bei was removed from Balhae by his brother, the emperor Taizong, Balhae was largely incorporated into the state but still retained a few privileges; for details see ibid., pp. 112-3

- ↑ Twitchett and Tietze, p. 70

- ↑ The Ning-Chang Prefecture was the main frontier trading station in the region, and the first to come under Jurchen attack. Twitchett and Tietze, p. 142

- ↑ Twitchett and Tietze, pp. 142-4

- ↑ Dawson, p. 141

- ↑ Twitchett and Tietze, pp. 97-8

- ↑ Twitchett and Tietze, p. 147

- ↑ Twitchett and Tietze, p. 117

- ↑ Twitchett and Tietze, pp. 149-50; Biran, p. 21

- ↑ Biran, pp. 1, 25-6; Twitchett and Tietze, pp. 151-3

References

- Biran, Michal. The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian History: Between China and the Islamic World. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-521-84226-3

- Dawson, Raymond Stanley. Imperial China. London: Hutchinson, 1972. ISBN 0-09-108480-6

- Hucker, Charles O. A Dictionary of Official Titles in Imperial China. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 1985. ISBN 0-8047-1193-3

- Mote, Frederick W. Imperial China, 900-1800. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-674-01212-7

- Twitchett, Denis, and Klaus-Peter Tietze. "The Liao." The Cambridge History of China, Volume 6: Alien regimes and border states, 907-1368. Ed. Herbert Franke and Denis Twitchett. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1994. ISBN 0-521-24331-9

- Wittfogel, Karl A., and Feng Chia-sheng. "History of Chinese Society, Liao (907-1125)." Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, Volume 36. Lancaster, PA: Lancaster Press Inc, 1949.