| 1913 Ipswich Mills strike | |||

|---|---|---|---|

A meeting of strikers at a local Greek churchyard | |||

| Date | April 22 – July 31, 1913[note 1] (3 months, 1 week and 2 days) | ||

| Location | Ipswich, Massachusetts, United States | ||

| Goals | 20 percent wage increase | ||

| Methods | |||

| Resulted in |

| ||

| Parties | |||

| |||

| Casualties | |||

| Death(s) | 1 | ||

The 1913 Ipswich Mills strike was a labor strike involving textile workers in Ipswich, Massachusetts, United States. The strike began on April 22 and ended in defeat for the strikers by the end of July.

The strike was organized by the Industrial Workers of the World, a labor union that had begun organizing the workers of the Ipswich Mills, a hosiery mill, in 1912. By 1913, many immigrant workers of the mill, primarily Greek and Polish people, began to demand an increase in wages, and on April 22, a walkout of a majority of the plant's workers (as many as 1,500) caused the mill to temporarily close. Town officials responded to the strike by bringing in additional police officers from nearby municipalities, and local media disparaged the strikers. On June 10, in an event known locally as "Bloody Tuesday", police opened fire on a group of strikers near the gates of the mill, killing one bystander and injuring several others. Afterwards, several union leaders were arrested, and the company began to evict striking workers from their company-owned homes. By the end of July, the strike had collapsed, and an October article in The Quincy Daily Ledger stated that by that time, many of the strikers had left Ipswich. Despite attracting national attention at the time, the strike ultimately fell into obscurity in Ipswich. However, since the 2010s, there has been increased interest in the historical event, which have included a presentation on the strike at the Ipswich Museum in 2013 (the 100th anniversary of the strike) and the installation of a memorial plaque for the strike and "Bloody Tuesday" in 2022.

Background

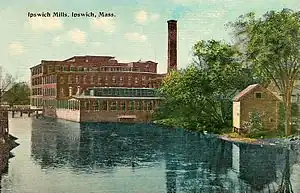

In the 1910s, the town of Ipswich, Massachusetts, was home to about 6,000 people.[3] Like many towns in the region during this time, Ipswich had a strong textile industry and was home to a large population of immigrants,[4] primarily Greeks and Poles.[5] The municipality operated as a company town for the Ipswich Mills, a large hosiery mill in downtown Ipswich.[5] Stockholders in this mill included several influential figures in the state, such as William Loring, a member of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, and William Lawrence, the bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts,[3] while the mill town itself was led by George Scofield,[note 2] a local politician and publisher of the Ipswich Chronicle newspaper.[5]

Workers in the mill often dealt with poor working conditions and low wages.[4] They were paid according to a piece rate and made between $2 and $7 (equivalent to between $59 and $207 in 2021) per 72-hour week.[note 3] These conditions made labor organizing an attractive choice for the workers, and in 1912, C. L. Pingree, a representative of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), arrived and began to organize the workers with that labor union.[3] The IWW had been established in 1905 and had had success in organizing millworkers in the region.[4] In 1912, Pingree pushed for the Ipswich Mills to enforce a state law stipulating a maximum workweek of 54 hours for the millworkers.[3][note 4] Additionally, the mill changed its policy regarding its notice period and paid out about $60,000 (equivalent to $1,777,000 in 2022) in back pay to workers who had previously quit without giving the company two weeks' notice.[3] During this time, many of the mill workers became IWW members.[3] As the workers began to organize, tensions began to rise between them and the millowners, and this reached a peak in mid-1913.[4] Workers began to demand better working conditions and higher wages,[6][7] with a pay increase of at least 20 percent.[note 5] A labor strike was organized to push for these demands,[5] with the IWW previously having led another textile strike in nearby Lawrence, Massachusetts.[4] That strike, which had involved about 20,000 mostly immigrant workers, had ended in success for the union, with an increase in wages for the workers.[4]

Course of the strike

Early strike action

On April 22, the strike began with a walkout that consisted of a majority of the workers at the mill, up to 1,500 people in total.[3] These strikers consisted primarily of non-English speaking immigrants, while about 500 English-speaking non-immigrants remained working.[2] The strike had the effect of idling the mill for about a month.[9] Over the next several weeks, several hundred strikers, primarily English-speakers, began to defect and return to work, though many Greek and Polish workers remained on the picket line.[10] The millowners and town officials, such as Scofield,[5] were sternly against the strikers' demands and began to bring in strikebreakers from Boston.[6] During the strike, additional police officers were brought in from nearby towns,[4] such as Lawrence, Beverly, and Salem.[10] This increased expenditure for police put a strain on the town's budget, and a meeting of town officials was scheduled for June 10 to discuss allocating more funds for the police.[10]

"Bloody Tuesday"

"They shot the Greek girl and killed her … She wasn't even a striker. I come out and tried to help, and they shoot me in the leg. My sister comes out with a baby in her hands, and they shoot her. My second sister called for help, and they club her. My mother comes out, and they started to shoot her. All they wanted is to shoot the goddamn foreigners"

-Steve Georgakopoulos, a millworker at the time of the strike and eyewitness to the shooting, during a 1984 interview[4]

On the evening of Tuesday, June 10, a large group of strikers were picketing near the front gates of the mill.[10] According to a contemporary report from the International Socialist Review, there was a confrontation between some of the picketers and strikebreakers, and a group of police began to arrest some of the strikers.[10] A town councilor read the riot act to the group, but as many of the picketers spoke only Greek, they probably did not understand what was being said.[5][6] As police continued to try to disperse the crowd, the strikers resisted, and police began to fire their guns into the crowd.[11] Within five minutes, between 50 and 100 shots had been fired by the police.[5][6] The incident, known locally as "Bloody Tuesday",[6] resulted in the death of one woman and injuries to seven others.[11][note 6] The woman, Nicholetta Paudelopoulou,[note 7] was struck in the head with a bullet and declared dead shortly after arriving at a local hospital.[5][4] Paudelopoulou was a worker at the mill who had not been involved in the strike, but was returning home from the mill when the shooting began.[6] Many of the injured were treated at Salem Hospital and faced steep medical bills upon their release.[4]

Following the shooting, several individuals associated with the strike, including three IWW leaders,[4] were arrested.[5][6] Those arrested were charged with murder,[10] as police officers claimed that Paudelopoulou had been killed by someone firing a gun from a nearby second-story vantage point.[5] Additionally, the police claimed that they had been fired on first before they began to fire into the crowd.[5][6] However, a medical examiner ruled that that was impossible and that Paudelopoulou's gunshot wound had most likely been caused by someone firing level to her.[5] Additionally, during the ensuing trial, no evidence was presented to substantiate the police's claim that they had been initially fired upon.[5][6] The case ultimately collapsed due to a lack of evidence,[5][6] and the IWW leaders were found innocent.[12] No police were ever charged for the death of Paudelopoulou.[5][6] During the period immediately following the shooting, the Ipswich Chronicle published a series of reports that disparaged the strikers.[5][6]

Later strike activities

On the evening of June 10, the same day as "Bloody Tuesday", the town government appropriated a further $12,000 (equivalent to $355,000 in 2022) for the police.[10] Following the shooting, the police began to crack down on meetings and parades held by the strikers, and, in an effort to avoid this, strikers began to hold meetings in the yard of a local Greek church.[10] However, police arrested many outside speakers who were present at these meetings.[1] By early July, the strike was still ongoing, but around this time, the mill began to evict striking families from their homes, a possibility that the mill had made clear much earlier in the strike.[4] At least 14 families were evicted from their company-owned houses during the strike.[2] According to Ipswich historian Gordon Harris, the strike petered out and was over by the end of July.[2] In October 1913, The Quincy Daily Ledger reported that, by that time, many of the strikers who had been involved in the strike had been evicted and had relocated from Ipswich.[13]

Aftermath

At the time, the strike received national attention, including coverage in a newspaper as far away as Honolulu.[12] However, over the next several decades, there was little acknowledgement of the strike from the town itself, as highlighted in a 2013 report on the strike given by several Ipswich High School students at the Ipswich Museum.[12] In October 2021, the Ipswich Historical Commission voted to create a plaque commemorating the strike and the death of Paudelopoulou.[5] On June 10, 2022, the 109th anniversary of "Bloody Tuesday",[6] the plaque was dedicated near the site of the event,[14][7] on property now owned by EBSCO Industries.[5] The event included a procession of dozens of individuals from the Assumption of the Virgin Mary Greek Orthodox Church to the plaque in downtown.[14]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Sources are unclear regarding an official end date for the strike. While an August 1913 article in the International Socialist Review mentioned that the strike was still ongoing in early July,[1] Ipswich historian Gordon Harris stated in 2018 that, "By the end of the month the strike was broken, and laborers went back to work". July 31 thus represents the latest end date for the strike.[2]

- ↑ Also given as "Schofield" in some sources.[2]

- ↑ Sources vary on the exact range of pay. Stewart Lytle of The Town Common newspaper stated in 2021 and 2022 articles that the workers made between $2 and $7 per week.[5][6] Meanwhile, J. S. Biscay wrote in a 1913 article in the International Socialist Review that workers made between $2 and $6.[3] In a 1984 interview, Steve Georgakopoulos, who worked at the mill in 1913, stated that he made $4.16 per week, with a range of between $2.50 and $7.[2]

- ↑ According to a 1913 article in the International Socialist Review, the millowners had ignored the 54-hour law,[3] a statement supported by a 1984 interview with a worker of the mill, who stated that many people at that time, himself included, worked 72 hours per week at the mill.[2]

- ↑ Sources vary on the exact demands of the workers during this time. Stewart Lytle, in 2021 and 2022 articles for The Town Common, states that the workers wanted a 20 percent wage increase,[5][6] a figure also given by Ipswich historian Gordon Harris in 2018.[2] However, in a 1914 article for The Survey, Edgar Fletcher Allen reported that, when asked about their demands, some workers stated that they wanted a 40 percent increase.[8]

- ↑ The figure of seven injuries comes from a 1969 report prepared by historians Hugh Davis Graham and Ted Robert Gurr for the federal government of the United States.[11] However, a contemporary report in the International Socialist Review states that ten people in total were treated for injuries at local hospitals following the shooting.[10]

- ↑ Also given in some sources as "Nicolette Pandepolus",[12] "Nicoletta Papadopoulou",[2] and "Nicoletes Pandeloppoulou".[13]

References

- 1 2 Biscay 1913, p. 92.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Harris 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Biscay 1913, p. 90.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Ashlock 2022a.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Lytle 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Lytle 2022.

- 1 2 Ipswich Local News 2022.

- ↑ Allen 1914, p. 217.

- ↑ Biscay 1913, pp. 90–91.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Biscay 1913, p. 91.

- 1 2 3 Graham & Gurr 1969, p. 252.

- 1 2 3 4 Zagarella 2013.

- 1 2 The Quincy Daily Ledger 1913, p. 4.

- 1 2 Ashlock 2022b.

Sources

- Allen, Edgar Fletcher (May 23, 1914). Kellogg, Paul U. (ed.). "Aftermath of Industrial War at Ipswich, Mass". The Survey. New York City. XXXII (8): 216–217.

- Ashlock, Tristan (March 27, 2022a). "Acknowledging History: The Strike of 1913 and Ipswich's Commitment to Remembrance". Ipswich Local News. Archived from the original on June 4, 2022. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Ashlock, Tristan (June 14, 2022b). "Ipswich dedicates memorial to victims of 1913 Ipswich Mill strike". Ipswich Local News. Archived from the original on August 28, 2022. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Biscay, J. S. (August 1913). Kerr, Charles H. (ed.). "The Ipswich Strike" (PDF). International Socialist Review. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Co. XIV (2): 90–92 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- Graham, Hugh Davis; Gurr, Ted Robert (June 1969). Violence in America: Historical and Comparative Perspectives. A Report to the National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence. Vol. I. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. LCCN 76601931.

- Harris, Gordon (January 24, 2018). "Police open fire at the Ipswich Mills Strike, June 10, 1913". Historic Ipswich. Archived from the original on October 1, 2022. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- "Bloody Tuesday memorial set for June 10". Ipswich Local News. May 30, 2022. Archived from the original on June 7, 2022. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- Lytle, Stewart (October 13, 2021). "Ipswich Mill Strike to be Honored". The Town Common. Archived from the original on December 9, 2022. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- Lytle, Stewart (June 22, 2022). "'Bloody Tuesday' Strike Honored". The Town Common. Archived from the original on November 28, 2022. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- "Riot Trial Begun". The Quincy Daily Ledger. Vol. 28, no. 241. October 17, 1913. p. 4.

- Zagarella, Gus (December 28, 2013) [December 27, 2013]. "Students shine light on century-old Ipswich tragedy". Wicked Local. Gannett. Archived from the original on February 20, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

Further reading

- Muldoon, John P. (June 10, 2015). "Riots, Ethnic Tension: Police Open Fire, 1 Killed, 7 Injured". Ipswich Local News. Archived from the original on October 6, 2022. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- "A 27-year-old Woman Died in a 1913 Ipswich Mill Strike; She Never Did Get Justice". New England Historical Society. 2022 [March 8, 2017]. Archived from the original on December 2, 2022. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- "Riot Bullets Kill Woman, Hurt Seven; Many Others Injured in Strikers' Battle with Police at Ipswich Mill". The New York Times. June 11, 1913. p. 7. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 20, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.