Index: Races | Winners | |||

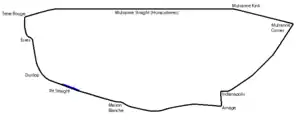

The 1953 24 Hours of Le Mans was the 21st Grand Prix of Endurance, and took place on 13 and 14 June 1953, at the Circuit de la Sarthe, Le Mans (France). It was also the third round of the F.I.A. World Sports Car Championship.[1]

British drivers Tony Rolt and Duncan Hamilton won the race with one of three factory-entered Jaguar C-Types, the first cars ever to race at Le Mans with disc brakes.

Regulations

With the ongoing success of the World Championship of Drivers, this year saw the introduction by the FIA of a World Championship for Sports Cars, creating great interest from the major sports car manufacturers.[2] It also drew together the great endurance races in Europe and North America. The Le Mans race was the third round in the championship after the 12 Hours of Sebring and the Mille Miglia.

After the efforts by drivers in the recent races to drive almost single-handedly (Chinetti in 1949, Rosier and Hall in 1950, Levegh and Cunningham in 1952) and the consequent safety danger through exhaustion, the ACO set limits of maximum driving spells of 80 consecutive laps and 18 hours in total for each driver.

This year also marked the first use of a radar-‘gun’ to measure speeds across a flying kilometre on the Hunaudières Straight. The Cunningham would touch almost 156mph. Some 6 mph faster than last years winning Mercedes gull wing coupe. These results, not surprisingly, aligned with engine size but, significantly, also the impact of aerodynamics on top speed:[3][4]

| Nation | Manufacturer | Engine | Top Speed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cunningham C-5R | Chrysler 5.45L V8 | 249.1 km/h | |

| Alfa Romeo 6C/3000CM | Alfa Romeo 3.5L S6 | 245.9 km/h | |

| Jaguar C-Type | Jaguar 3.45L S6 | 244.6 km/h | |

| Ferrari 340 MM | Ferrari 4.1L V12 | 242.1 km/h | |

| Talbot-Lago T26 GS | Talbot-Lago 4.5L S6 | 239.1 km/h | |

| Gordini T26S | Gordini 2.5L S6 | 233.9 km/h | |

| Allard J2R | Cadillac 5.4L V8 | 233.8 km/h | |

| Lancia D.20 | Lancia 2.7L V6 s/c | 219.6 km/h | |

| Aston Martin DB3S | Aston Martin 2.9L S6 | 212.2 km/h | |

| Porsche 550 Coupé | Porsche 1.5L F4 | 197.7 km/h | |

| DB HBR-4 LM | Panhard 0.7L F2 | 160.6 km/h | |

| Panhard X88 | Panhard 0.6L F2 | 169.8 km/h | |

Entries

The prestige of the race, as well as the advent of the new championship generated intense interest in Le Mans. Of the 69 entrants and reserves, nineteen different marques (and their subsidiaries) were present. There were an unprecedented 56 works-entered cars officially represented, with over half in the main S-8000, S-5000 and S-3000 classes. Mercedes-Benz did not return to defend their title – they were busy preparing new cars for both the F1 and Sports Car championships. So the overall victory was shaping up as a contest between Italy (Scuderia Ferrari, S.P.A. Alfa Romeo and Scuderia Lancia), England (Jaguar supported by Aston Martin, Allard and Nash-Healey/Austin-Healey and the United States (Cunningham), with the French (Talbot and Gordini) being the ‘dark horses’.

Drivers included all three F1 World Champions to date (Alberto Ascari, Juan Manuel Fangio, Giuseppe Farina) and over 30 other current and up-and-coming Grand Prix racers.[5]

The Italian teams had built new cars for the season and all had strong driver line-ups.[2][6] Ferrari entered two lightweight Ferrari 340 MM Berlinettas powered by the company's big 280 bhp 4.1 litre V12 engine built for a challenge at Mille Miglia,[7][4] All had Pinin Farina-designed bodies. Ascari and Luigi Villoresi were to share another lightweight coupé 375 MM converted to 4.5-litres,[8] while brothers Paolo and Gianni Marzotto (winner of the 2nd round of the championship: the Mille Miglia) and Giuseppe Farina and debutante Mike Hawthorn were down to drive the 340 MMs.[6] A third 340 MM Spyder was entered by American Ferrari agent Luigi Chinetti for himself, with Anglo-American Tom Cole (who had finished 3rd with Allard in 1950) as his co-driver. Such was the quality of the entry list that six other Ferraris could not make the starting list.[7]

Alfa Romeo was back at Le Mans for the first time since the war and fielded the beautiful new 6C/3000CM (‘’Cortemaggiore’’) powered by a 3.5L S6 engine (developing 270 bhp and 245 km/h) for Fangio and Onofre Marimón and Consalvo Sanesi and Piero Carini. The third car was driven by Mercedes-Benz works-drivers Karl Kling and Fritz Riess who also had their team manager, Alfred Neubauer, in the pits with them.[9] Lancia this year stepped up to the big class with three new D.20 Coupés. Having just won the non-Championship Targa Florio with a 3.0L V6 engine, team manager Vittorio Jano instead decided to install supercharged 2.7L engines. This proved to be a mistake as the small increase in power (to 240 bhp) increased unreliability and gave away over 20 km/h top speed to the rival Jaguars and Ferraris. GP-racers Louis Chiron and Robert Manzon, Piero Taruffi and Umberto Maglioli were in the team, with José Froilán González and endurance-race specialist Clemente Biondetti in the reserve car.[6]

Jaguar returned with their C-Types and after the debacle of the previous year, were determined not to repeat those mistakes, having undertaken a lot of development work. Team manager ‘Lofty’ England employed the same driver pairings as 1952, with Peter Walker and Stirling Moss, Peter Whitehead and Ian Stewart, and Tony Rolt and Duncan Hamilton. The cars reverted to the aerodynamic design prior to that of the 1952 Le Mans cars, whose revised nose and tail had adversely affected stability at speeds over 120 mph. For 1953 the cars were lighter and more powerful (now developing 218 bhp), and they were the first-ever Le Mans cars equipped with disc brakes, from Dunlop, whose greater efficiency gave the C-Types a distinct advantage over their drum-braked competitors.[10] The disc brakes had been available in 1952, but given the problems with the radiators they had been swapped out so the team could concentrate on just one potential issue in the race.[11] The works cars were supported by a standard production-body car entered by the new Belgian Ecurie Francorchamps team.[12]

Aston Martin entered their new DB3S cars for Reg Parnell and Peter Collins, George Abecassis and Roy Salvadori, and Eric Thompson and Dennis Poore. Using the same 3-litre engine as the DB3, it was put into a newly designed, shortened, chassis. However it was suffering from considerable lack of testing, being well down on speed.[13]

Donald Healey this year had two collaborations: his last year with Nash Motors with a pair of long-tailed models, and a new partnership with the Austin Motor Company using its 2.7L engine, producing only 100 bhp but capable of 190 km/h. Bristol also arrived with two cars for Lance Macklin / Graham Whitehead and Jack Fairman / Tommy Wisdom, and managed by former Bentley Boy and Le Mans winner Sammy Davis. The rear-engined 450 coupés were ugly and noisy but the 2 litre engine could get them to nearly 230 km/h.[6][14] Briggs Cunningham also brought three cars, all with 310 bhp 5.5L Chrysler V8 engines: a new C-5R (nicknamed “Le Requin” (the shark) by the French)[12] for Phil Walters and John Fitch who had won the inaugural championship race at Sebring; a C-4R for Cunningham himself and William "Bill" Spear and, a C-4RK coupé for veteran Charley Moran (the first American to race at Le Mans, back in 1929)[12] and Anglo-American John Gordon Bennett.

This year Talbot entered a full works-team, rather than just providing support to privateer entries. The trio of blue T26 GS cars were driven by Talbot regulars Guy Mairesse (with Georges Grignard), Louis Rosier and Elie Bayol, and Pierre Levegh and Charles Pozzi. Although still very fast, they were starting to show their age to the nimbler cars from Italy and Great Britain. André Chambas also returned with his supercharged modified SS spyder for a 5th and final time.[15][16] Gordini had intended to debut the new 3.0L T24S, but scratched it because of atrocious handling. Instead an uprated T16 design, the T26S with a 2.5L engine was prepared for Maurice Trintignant and Harry Schell. An older T15S was entered for Behra and Mieres. Though it only had a 2.3L engine it was lighter, and just as quick as its bigger brother.[17]

Without Mercedes-Benz, German representation fell to works teams from Borgward (here for the first and only time) and Porsche, both in the medium S-1500 class. Porsche stepped up from the S-1100 class with a new, purpose-designed race car, the 550 Coupé and its flat-four 1488cc engine, making only 78 bhp but a top speed of nearly 200 km/h.[18] There were also a pair of the smaller 356 SL in the S-1100 class.

As expected the French dominated the smaller-engined classes. The most eye-catching were the four from Panhard, bringing cars with their own badge this time under a new competition department, albeit under close collaboration with Monopole: with very aerodynamic designs from French aviation engineer Marcel Riffard using both of the Panhard engines.[19] Other works entries came from Renault, DB and Monopole themselves.

Practice

In Thursday practice the Jaguars showed their class with all three works cars going under the lap record, but drama also happened when the 3rd car, of Rolt and Hamilton, was disqualified. It had been on track at the same time as another Jaguar which had the same racing number (the spare car being used as a precaution to qualify Norman Dewis, the Jaguar test driver, as a reserve), and a protest raised by the Ferrari team. Jaguar chairman, Sir William Lyon, agreed to pay the ACO fine, and ‘Lofty’ England successfully pleaded his case to the official that no intention to cheat had been meant and it was an honest mistake and so they were reinstated. But Hamilton's account of the affair has become one of the great motor racing legends:[20] Devastated by their disqualification, he & Rolt had gone into the city for the night to drown their sorrows, and when England found them at 10am the next day (race-day) at Gruber's restaurant, they were nursing hangovers and drinking copious amounts of coffee![21] Unfortunately, such a colourful story is an urban myth: England later said: "Of course I would never have let them race under the influence. I had enough trouble when they were sober!"[22] Tony Rolt also said the story was fiction.[23]

The Spanish Pegaso team withdrew both their entries after Juan Jover crashed his Z-102 Spyder during practice. Misjudging the speed of his approach to the corner after the Dunlop bridge, he hit the barriers at over 200 km/h and was thrown from the car, seriously injuring his left leg. With no apparent explanation for the crash, the team decided on safety first and scratched the other car. It was the first and last time they got to Le Mans.[24]

Race

Start

At 4:00pm on the Saturday, the flag fell and the race was on. As usual, Moss was lightning-quick out of the blocks and led the cars away, but the Allard blasted past him on the Mulsanne straight and was leading the closely bunched field at the end of the first lap. But Sydney Allard’s early lead barely lasted, and by lap four he had to retire with a collapsed rear suspension that severed a brake pipe. The first few laps at Le Mans means very little and it was not until after 30 minutes that the true nature of the race became apparent. Rolt had already put in a lap record at 96.48 mph, while Moss led the way, closely followed by Villoresi, Cole, Rolt, Fitch, with Karl Kling rounding out the top six. But Moss was also soon in trouble. Although he had smoothly pulled away from the chasing pack, a misfire had set in after only 20 laps, in the second hour. The unscheduled pitstop to change spark plugs, plus another later for the eventual fix – removal of a clogged fuel filter – dropped the car well down to 21st.[10] At least Jaguar had remembered the pit regulations: A Ferrari mechanic topped up the brake system on Mike Hawthorn’s 340 MM before the specified 28 laps had been completed, thereby Hawthorn/Farina were disqualified.[7] Whilst all this was going on, Villoresi had taken the lead.[5][25]

By 5pm, at the end of the first hour, the order had settled down and it became clear that the Jaguars, Ferraris and Alfa Romeos were the teams to be reckoned with. The Lancias and Talbots were quite outclassed, as were the medium-engined Aston Martins. The race continued at a fantastic pace and now it was Jaguar setting it: passing Villoresi, Rolt lifted his lap times by 5 seconds to push his lead.[21] Then Consalvo Sanesi, in his Alfa Romeo 6C, continued to lower the lap record. Just before 6:00pm, Fangio retired with engine troubles in his Alfa Romeo. At the three-hour mark, Rolt/Hamilton led from Ascari/Villoresi, followed by Cole and his co-driver Luigi Chinetti, Sanesi/Carini, and the Germans Kling and Riess. Already these five cars had pull out a two lap advantage over the rest of the field.[25]

Night

As darkness fell, the Ferrari-Jaguar battle continued unabated, between Ascari/Villoresi and Rolt/Hamilton, with the Alfa Romeos close behind and the overall order swapping around according to pit-strategy.[26] During the early hours of the morning, Rolt and Hamilton continued to lead with no sign of tiring, while the Ferrari was now losing ground – the big engine starting to stretch the rest of the powertrain.[7]

The Gordinis were once again punching above their weight, mixing it in the top-10 with the third works Jaguar, the other Ferraris and the Cunninghams. The smaller-engined car was a high as 7th ahead of its stable-mate until its rear-axle seized, necessitating long repairs that proved terminal soon after midnight.[17] In the other classes the Porsche 550s had the measure of all the smaller cars and, aside from those superfast Gordinis, were even running ahead of the S2.0 and S3.0 cars.

Just after midnight, Tommy Wisdom's Bristol had an engine fire (almost an identical problem had hit its sister-car earlier in the evening). Crashing, Wisdom was trapped for a short while before being rescued and taken to hospital with minor burns and a dislocated shoulder.[14]

Then just before 3am, the rear suspension on the Sanesi/Carini Alfa Romeo had collapsed, and they were out, along with George Abecassis and Roy Salvadori with oil getting into their Aston Martin's clutch.[13][25][26]

Although the Ascari and Villoresi car was still taking the fight to the Jaguars, the car was hindered by a sticking clutch and drinking a lot of water. However, the Italians, in a win-or-bust attempt, were driving flat out at all times, but it had no effect on Rolt and Hamilton. Their Jaguar now had a lap lead over the Ferrari.[25]

Morning

Despite the night being very clear and fine, dawn approached with a certain amount of mist in the air, making driving conditions very tiring.[26] Just after 6.30am Tom Cole, running 7th, had just overtaken a back-marker when he lost control at the Maison Blanche corners. The Ferrari ploughed into the roadside ditch then rolled and struck a wooden hut nearby. Cole was hurled out of the car in the initial impact and died at the scene.[6][25]

The windscreen on the leading Jaguar had been smashed early in the race by bird-strike,[21] and as result Rolt and Hamilton were suffering from wind buffering, but the pair kept up the pace nevertheless, with an average speed of well over 105 mph. By the time the mist had cleared, Rolt and Hamilton still led by a lap from the struggling Ferrari. Third place, over three laps adrift, was the Cunningham of Fitch/Walters and a lap further back were the fast Jaguars of Moss/Walker (back in the race after a terrific hard drive back through the field) and Whitehead/Stewart.

Shortly after 8:30am, the leading Jaguar and Ferrari both made routine refuelling stops at the same time. Hamilton had what would now be termed an “unsafe release” when, in the rush to beat the Ferrari, he pulled out right in front of one of the DB-Panhards coming in for its own pitstop.[21] Walters had a big moment when his Cunningham blew a tyre at high speed but he was able to catch it. But with the subsequent pitstop to fix the damage, Moss was able to move up to third.[12] By 9:00am, the clutch issues with the lead Ferrari gave it a long stop, and it was now back in fifth place. This left Rolt and Hamilton clear up front, but they could not rest as Fitch and Walters started to fight back and hound the Moss/Walker Jaguar for second place.[6][25][27][28][7]

The lame Ferrari retired just before 11am having dropped down the order to sixth place. This left only the Marzotto car to challenge the Jaguars and the lead Cunningham. It could not do it and raced to finish in fifth, keeping the Gordini of Maurice Trintignant and Harry Schell behind them.[25]

The Lancias had never made an impression, none having made it into the top-10 and just after midday the engine of the last one running (of González and Biondetti) gave up.

Finish and post-race

_at_Greenwich%252C_2018.jpg.webp)

With three hours to ago, the Jaguars were still lapping at over 105 mph, however the pace had slackened a little. In the closing stages the order did not change, as Hamilton took over from Rolt to complete the last stage of the race. Driving their British license-plated Jaguar C-Type they took the victory, covering a distance of 2,555.04 miles (4,088.064 km), doing 304 laps and averaging a speed of 106.46 mph (170.336 km/h). Moss and Walker were four laps adrift at the finish, in second place with their C-Type after their epic drive. The podium was completed by Walters and Fitch, in their Cunningham C-5R a lap back. The third works Jaguar finished fourth, two laps further behind the Americans, after a very conservative and reliable race.[25]

The Marzotto brothers brought home the sole remaining Ferrari in fifth, finishing with virtually no clutch but having stayed in the top 10 throughout the race.[7] A lap back was the Gordini, having had a trouble-free run.[17] Owner-driver Briggs Cunningham came in 7th followed by the works Talbot of Levegh, finishing this year, and the private Jaguar, entered by Ecurie Francorchamps for Roger Laurent and Charles de Tornaco, in their standard C-Type.[5][25][29][30]

In a race of attrition where only 1 car, if any, of the many other works teams finished, it was an effort of remarkable reliability that all cars of the Jaguar, Cunningham and Panhard works teams finished.[27] The Panhard team staged a formation finish, winning the Index of Performance by the narrowest of margins.[12]

As expected, the Porsches finished 1–2 in the S-1500 class with the win going to the car driven by racing journalists Paul Frère and Richard von Frankenberg

The little DB-Panhards had an extraordinary run, that of owner-driver René Bonnet winning the S-750 class ahead of its sister car, and finishing 5 laps clear of the OSCA winning the bigger S-1100 class. They were on course for the coveted Index of Performance win, but a bad engine misfire meant it used too much fuel on its very last lap. The streamlined Panhard won the Index by the tiniest fraction on a countback.[31]

Records were broken across the board – the first time a car completed the race with an average speed over 100 mph (in fact the first six finishers did) and covered over 2500 miles (4000 km). All the categories broke their class records, and a new lap record was set.[27]

With such a varied and competitive field there could be no better advertisement for the new Sports Car Championship going forward. However, it would be without several teams: after dominating the early Formula 1 championship, and a semi-successful year in sports cars, Alfa Romeo withdrew from motor racing. Jowett was already in receivership and it would also be the last Le Mans for Allard, Lancia and Nash-Healey.

Official results

Results taken from Quentin Spurring's book, officially licensed by the ACO[32]

- Note: Not Classified because of Insufficient distance, as car failed to cover 70% of its class-winner's distance.

Did Not Finish

| Pos | Class | No | Team | Drivers | Chassis | Engine | Laps | Reason |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 27 | S 5.0 |

12 | Ferrari 375 MM Berlinetta | Ferrari 4.5L V12 | 229 | Clutch (20hr) | ||

| 28 | S 1.5 |

41 | Borgward-Hansa 1500 ‘Rennsport’ | Borgward 1498cc S4 | 228 | Overheating (24hr) | ||

| 29 | S 8.0 |

63 (Reserve) |

Lancia D20 | Lancia 2.7L V6 Supercharged |

213 | Engine (21hr) | ||

| 30 | S 3.0 |

27 | Aston Martin DB3S | Aston Martin 2.9L I6 | 182 | Engine (18hr) | ||

| 31 | S 5.0 |

16 | Ferrari 340 MM Vignale Spyder | Ferrari 4.1L V12 | 175 | Fatal accident (16hr) | ||

| 32 | S 8.0 |

31 | Lancia D20 | Lancia 2.7L V6 Supercharged |

174 | Engine (18hr) | ||

| 33 | S 1.1 |

49 | Porsche 356 SL | Porsche 1091cc F4 | 147 | Engine (18hr) | ||

| 34 | S 2.0 |

40 | Frazer Nash Le Mans MkII Replica | Bristol 1971cc S6 | 135 | Overheating (14hr) | ||

| 35 | S 5.0 |

23 | Alfa Romeo 6C 3000 CM | Alfa Romeo 3.5L S6 | 133 | Transmission (12hr) | ||

| 36 | S 5.0 |

21 | Alfa Romeo 6C 3000 CM | Alfa Romeo 3.5L S6 | 125 | Rear Suspension (12hr) | ||

| 37 | S 5.0 |

9 | Talbot-Lago T26 GS Spyder | Talbot-Lago 4.5L S6 | 120 | Engine (12hr) | ||

| 38 | S 8.0 |

30 | Lancia D20 | Lancia 2.7L V6 Supercharged |

117 | Electrics (12hr) | ||

| 39 | S 1.1 |

46 | (private entrant) |

Porsche 356 SL | Porsche 1091cc F4 | 115 | Engine (18hr) | |

| 40 | S 750 |

55 | (private entrant) |

Renault 4CV-1063 | Renault 747cc S4 | 84 | Engine (12hr) | |

| 41 | S 3.0 |

36 | Gordini T15S | Gordini 2.3L S6 | 84 | Transmission (10hr) | ||

| 42 | S 1.5 |

47 | O.S.C.A. MT-4 | O.S.C.A. 1343cc S4 | 80 | Transmission (10hr) | ||

| 43 | S 3.0 |

26 | Aston Martin DB3S | Aston Martin 2.9L S6 | 74 | Clutch (10hr) | ||

| 44 | S 2.0 |

38 | Bristol 450 Coupé | Bristol 1979cc S6 | 70 | Accident / Fire (10hr) | ||

| 45 | S 8.0 |

32 | Lancia D20 | Lancia 2.7L V6 Supercharged |

66 | Transmission (6hr) | ||

| 46 | S 8.0 |

5 | Allard J2R | Cadillac 5.4L V8 | 65 | Engine (10hr) | ||

| 47 | S 1.5 |

67 (Reserve) |

(private entrant) |

Gordini T15S | Gordini 1490cc S4 | 40 | Transmission (10hr) | |

| 48 | S 5.0 |

8 | Talbot-Lago T26 GS Spyder | Talbot-Lago 4.5L S6 | 37 | Transmission (4hr) | ||

| 49 | S 750 |

54 | D.B. 4CV-1066 | Renault 747L S4 | 35 | Engine (4hr) | ||

| 50 | S 2.0 |

37 | Bristol 450 Coupé | Bristol 1979cc S6 | 29 | Fire (10hr) | ||

| 51 | S 1.5 |

42 | Borgward-Hansa 1500 ‘Rennsport’ | Borgward 1498cc S4 | 29 | Out of fuel (4hr) | ||

| 52 | S +8.0 |

6 | (private entrant) |

Talbot-Lago SS Spyder | Talbot-Lago 4.5L S6 Supercharged |

24 | Accident (4hr) | |

| 53 | S 5.0 |

22 | Alfa Romeo 6C 3000 CM | Alfa Romeo 3.5L S6 | 22 | Engine (3hr) | ||

| 54 | S 3.0 |

25 | Aston Martin DB3S | Aston Martin 2.9L S6 | 16 | Accident (2hr) | ||

| 55 | S 750 |

52 | V.P. 4CV-1064 | Renault 747cc S4 | 14 | Engine (7hr) | ||

| 56 | S 5.0 |

14 | Ferrari 340 MM | Ferrari 4.1L V12 | 12 | Disqualified (1hr) | ||

| 57 | S 5.0 |

10 | Nash-Healey Sports | Nash 4.1L S6 | 9 | Engine (2hr) | ||

| 58 | S 750 |

59 | Monopole X84 | Panhard 612cc F2 | 9 | Engine (7hr) | ||

| 59 | S 2.0 |

62 | Fiat 8V | Fiat 1996cc V8 | 8 | Electrics (1hr) | ||

| 60 | S 8.0 |

4 | Allard J2R | Cadillac 5.4L V8 | 4 | Transmission (1hr) | ||

| DNS | S 1.5 |

43 | Borgward-Hansa 1500 ‘Rennsport’ | Borgward 1498cc S4 | 0 | withdrawn | ||

| DNS | S 3.0 |

28 | Pegaso Z-102 Spyder | Pegaso 2.8L V8 Supercharged |

0 | accident | ||

| DNS | S 3.0 |

29 | Pegaso Z-102 Spyder | Pegaso 2.8L V8 Supercharged |

0 | withdrawn |

Index of Performance

| Pos | Class | No | Team | Drivers | Chassis | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | S 750 |

61 | Panhard X88 | 1.319 | ||

| 2 | S 750 |

57 | D.B. HBR-4 LM | 1.317 | ||

| 3 | S 5.0 |

18 | Jaguar C-Type | 1.307 | ||

| 4 | S 3.0 |

35 | Gordini T26S | 1.301 | ||

| 5 | S 5.0 |

17 | Jaguar C-Type | 1.292 | ||

| 6 | S 750 |

58 | D.B. HBR-4 LM | 1.283 | ||

| 7 | S 5.0 |

19 | Jaguar C-Type | 1.279 | ||

| 8 | S 8.0 |

2 | Cunningham C-5R | 1.271 | ||

| 9 | S 5.0 |

15 | Ferrari 340 MM Berlinetta | 1.251 | ||

| 10 | S 750 |

60 | Monopole X85 | 1.250 | ||

- Note: Only the top ten positions are included in this set of standings. A score of 1.00 means meeting the minimum distance for the car, and a higher score is exceeding the nominal target distance.[33]

19th Rudge-Whitworth Biennial Cup (1952/1953)

| Pos | Class | No | Team | Drivers | Chassis | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | S 750 |

61 | Panhard X88 | 1.319 | ||

| 2 | S 8.0 |

1 | Cunningham C-4R | 1.233 | ||

| 3 | S 750 |

53 | Renault 4CV-1068 Spyder | 1.211 | ||

| 4 | S 5.0 |

11 | Nash-Healey 4-litre Sport | ? |

Statistics

Taken from Quentin Spurring's book, officially licensed by the ACO

- Fastest Lap in practice – Hamilton / Whitehead, #18 Jaguar C-Type – 4m 37.0s; 175.27 kp/h (108.91 mph)

- Fastest Lap – Alberto Ascari, #12 Ferrari 375 MM – 4m 27.4s; 181.64 kp/h (112.87 mph)

- Fastest Car in Speedtrap – #2 Cunningham C-4R – 249.14 kp/h (154.81 mph)

- Distance – 4088.06 km (2540.32 miles)

- Winner's Average Speed – 170.34 km/h (108.85 mph)

- Attendance – est. 200 000 (start)[34]

World Championship Standings after the race

| Pos | Championship | Points |

|---|---|---|

| 1= | 12 | |

| 12 | ||

| 3 | 11 | |

| 4 | 8 | |

| 5 | 6 | |

| 6 | 4 | |

| 7 | 4 | |

| 8= | 1 | |

| 1 |

Championship points were awarded for the first six places in each race in the order of 8-6-4-3-2-1. Manufacturers were only awarded points for their highest finishing car, with no points awarded for positions filled by additional cars.

- Citations

- ↑ "Le Mans 24 Hours 1953". Racing Sports Cars. 1953-06-14. Retrieved 2014-05-18.

- 1 2 Clausager 1982, p.85

- ↑ Moity 1974, p.51

- 1 2 Clarke 1997, p.91: Road & Track Sep 1953.

- 1 2 3 "Le Mans 1953: Jaguar's gigantic leap — History, Le Mans". Motor Sport Magazine. Retrieved 2014-05-18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Le Mans 1953". Sportscars.tv. Retrieved 2014-05-18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Spurring 2011, p.158

- ↑ "375 MM PF Berlinetta 0318AM". barchetta.cc. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- ↑ Spurring 2011, p.170

- 1 2 Spurring 2011, p.154

- ↑ Spurring 2011, p.126

- 1 2 3 4 5 Spurring 2011, p.156

- 1 2 Spurring 2011, p.169

- 1 2 Spurring 2011, p.167

- ↑ Spurring 2011, p.168

- ↑ Clarke 1997, p.77: Autocar June 1953

- 1 2 3 Spurring 2011, p.161

- ↑ Spurring 2011, p.164

- ↑ Spurring 2011, p.159

- ↑ Foreword by Earl Howe to "Touch Wood!" Archived 2009-02-28 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 3 August 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 Spurring 2011, p.155

- ↑ Daily Telegraph obituary of Tony Rolt, 2 February 2008. Retrieved on 3 August 2008.

- ↑ Obituary of Tony Rolt by Alan Henry, 9 February 2008. Retrieved on 3 August 2008.

- ↑ Spurring 2011, p.151

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "1953 Le Mans 24 Hours report — History, Le Mans". Motor Sport Magazine. Retrieved 2014-05-18.

- 1 2 3 Clarke 1997, p.85: Motor Jun 1953

- 1 2 3 Clausager 1982, p.86

- ↑ Spurring 2011, p.153

- ↑ "1953 24 Hours of Le Mans Results and Competitors". Experiencelemans.com. Retrieved 2014-05-18.

- ↑ 8/26/10 12:30pm 8/26/10 12:30pm. "1953 24 Hours of Le Mans: Night of the Disc Brakes". Jalopnik.com. Retrieved 2014-05-18.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Spurring 2011, p.163

- ↑ Spurring 2011, p.2

- ↑ Clarke 1997, p.88: Motor June 1953

- ↑ Clarke 1997, p.82: Motor June 1953

References

- Spurring, Quentin (2011) Le Mans 1949-59 Sherborne, Dorset: Evro Publishing ISBN 978-1-84425-537-5

- Clarke, R.M. - editor (1997) Le Mans 'The Jaguar Years 1949-1957' Cobham, Surrey: Brooklands Books ISBN 1-85520-357X

- Clausager, Anders (1982) Le Mans London: Arthur Barker Ltd ISBN 0-213-16846-4

- Laban, Brian (2001) Le Mans 24 Hours London: Virgin Books ISBN 1-85227-971-0

- Moity, Christian (1974) The Le Mans 24 Hour Race 1949-1973 Radnor, Pennsylvania: Chilton Book Co ISBN 0-8019-6290-0

- Pomeroy, L. & Walkerley, R. - editors (1954) The Motor Year Book 1954 Bath: The Pitman Press

External links

- Racing Sports Cars – Le Mans 24 Hours 1953 entries, results, technical detail. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- Le Mans History – Le Mans History, hour-by-hour (incl. pictures, YouTube links). Retrieved 20 October 2016..

- Formula 2 – Le Mans 1953 results & reserve entries. Retrieved 20 October 2016.