Index: Races | Winners | |||

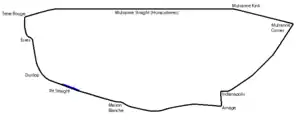

The 1958 24 Hours of Le Mans was the 26th running of the 24 Hours of Le Mans, Grand Prix of Endurance, and took place on 21 and 22 June 1958, on the Circuit de la Sarthe. It was also the fifth round of the 1958 World Sports Car Championship, which was running to new regulations introduced at the beginning of the season. Some 150,000 spectators had gathered for Europe's classic sports car race, around the 8.38-mile course. The prospect of an exciting duel between Ferrari, Jaguar, Aston Martin and giantkiller Porsche was enough to draw large crowds to the 24 Hours race.

The race was dominated by fifteen hours of rain, three of which were torrential, marking a bad summer solstice.[1] There were thirteen accidents, one killing gentleman-driver Jean-Marie Brussin. It marked the first ever overall win for an American and a Belgian driver and was the third win for the Scuderia Ferrari. The works Testarossas took over the lead in the third hour when, this year, it was the British challenge that ran out of steam. After their 1957 rout, the Italians took their revenge as Osca also won the Index of Performance.

Regulations

This year, the second under the new FIA Appendix C rules, a revision put a maximum engine size of 3.0 litres. This was an effort to limit the very high speeds of the new Maserati and Ferrari prototypes (and, indirectly ruling out the Jaguars) in the Sportscar Championship. The equivalence for forced-induction engines (supercharged or turbo) was reduced from x1.4 down to only x1.2 to encourage manufacturers to utilise that technology.

For the race itself, the Automobile Club de l'Ouest (ACO) allowed an increase of a driver's stint to a maximum of 40 laps (from 36), although the 14-hour total limit was still in place. Pushing a car anywhere on the track, aside from in the pit-line, was now no longer allowed.[2][1]

Following Colin Chapman's example for Lotus in the previous year, many cars adopted the ‘wraparound’ windscreen to meet the official dimension requirements. This year Chapman introduced tonneau-covers for the passenger seat to reduce draught and air resistance.[1]

Entries

A total of 70 cars registered for the event, of which 59 were allowed to practice, to qualify for the 55 starting places event.[3][4][5]

| Category | Classes | Entries |

|---|---|---|

| Large-engines | S-3000 | 21 (+2 reserves) |

| Medium-engines | S-2000 / S-1500 | 15 (+2 reserves) |

| Small-engines | S-1100 / S-750 | 19 (+3 reserves) |

The duels of the previous years between Jaguar and Ferrari were trimmed back by the new engine restriction. Although those manufacturers arrived with new engines, it also made Aston Martin (fresh from their triumph on the 1000km of Nürburgring) much more competitive, already with its tried and tested 3-litre engine. In the main class, only Ferrari and Aston Martin sent works entries.

Although defending champions Jaguar had no works team, they developed the new short-stroke 3-litre XK-engine, using carburettors not fuel-injection, to meet the 3.0L regulations for their customer teams.[6] It operated at around 5500–7000rpm, instead of the 4500–5800rpm of the previous bigger engines.[7] Winners of the past two races the Ecurie Ecosse team had two cars, for Ninian Sanderson/’Jock’ Lawrence and Jack Fairman/Masten Gregory The three other privateers included former winners Duncan Hamilton driving with Ivor Bueb. Also using the new 3-litre Jaguar motor was the new, small British manufacturer Lister, with two cars. Brian Lister had already been very successful in Britain however his lead driver, Archie Scott-Brown had been tragically killed at a sports-car race at Spa-Francorchamps just three weeks earlier.

Ferrari again arrived with a mighty force with no less than eleven cars for their works and private teams. Just prior to the meeting, Enzo Ferrari decided not to enter his latest two prototypes, reasoning that his well proven 3-litre 12-cylinder Testa Rossa was just the car for the circuit, and his best drivers. The pairings mostly came from the Ferrari F1 works team: Mike Hawthorn/Peter Collins, Phil Hill/Olivier Gendebien and Wolfgang von Trips/Wolfgang Seidel (called in to replace Luigi Musso injured in the previous weekend's Belgian Grand Prix). A fourth car was planned but Gino Munaron was also injured. The factory was backed up by no less than six other privately entered Testa Rossas, including two for Luigi Chinetti’s new North American Racing Team (NART) and single entries for Le Mans regulars Equipe Nationale Belge and Equipe Los Amigos.[8][9] A 2-litre Ferrari was entered for the Mexican Rodriguez brothers. However, Ricardo was judged to be too young (16 years old) by the ACO, and not allowed to start so he was replaced by José Behra (Jean Behra’s brother).[6][1][10]

Without its big engines and now in serious financial trouble, Maserati did not put in an effort this year, with only two private entries: in the 3-litre and a 2-litre classes.[11]

The new regulations suited Aston Martin very well, as they had already been running 3-litre cars for several years. They entered three of their updated DBR1s, as well as a privateer entry for the Whitehead brothers running a three-year-old Aston Martin DB3S (the runner-up car in 1955[12]). The strong driver line-up in the works team consisted of Stirling Moss/Jack Brabham, Tony Brooks/Maurice Trintignant and Roy Salvadori/ Stuart Lewis-Evans.[6][8][9]

After its success in the previous year, Lotus returned with four works cars and two private entries. It was only a month after Cliff Allison came sixth after the team's auspicious F1 début at the Monaco Grand Prix. For this race, they put at least one car in 4 classes. The new Lotus 15 was designed by Frank Costin and carried several Coventry-Climax engine options: a 2-litre, 1.5-litre or even 750cc (for the affiliated Equipe Lotus France privateer team). Colin Chapman also got Coventry Climax to develop a new 741cc engine based on their 650cc lightweight boat engine. Finally, there were also a pair of older Lotus 11 models to contest the S-1100 class

The S-2000 class had a diverse group of eight entries: aside from the new Lotus and the privateer Maserati, AC returned with two entries, one based around a John Tojeiro design. NART had a Ferrari 500 TR, and the British company Peerless entered a true GT car, with a Triumph engine.

Porsche, having dominated the S-1500 class now broadened their focus by uprating two of their three works 718 RSKs with 1.6L engines. The 718RSK in the S-1500 was supported by three privately entered 550A cars. As well as a works Lotus there were two Alfa Romeo Giuliettas from the Italian Squadra Virgilio Conrero team.

The reduced S-1100 class was the preserve of the Coventry Climax engine – two Lotuses and a car from the new specialist designer John Tojeiro. There was a big field in the smallest S-750 class and dominated by works entries: defending champions Lotus had two cars; from France were three from Deutsch et Bonnet, four from Monopole and one from specialist VP-Renault. Italy had a pair of OSCAs and four from Stanguellini

Practice

After the success of the vintage cars in the previous year, this year on the Friday evening the ACO held a 1-hour regularity trial for classic Le Mans race-cars.[2]

Qualifying was held over three sessions for a total of 660 minutes over the Wednesday and Thursday. Most of the qualifying runs took place on a dry track and the best time was achieved by Moss, who pushed his Aston Martin around in time of 4:07, averaging 121.7 mph. Next quickest were Brooks and most of his Aston Martin teammates, ahead of the rest of the field. Fastest Jaguar went to Fairman, who did 4 min 13 sec, a time matched by Hawthorn in his Ferrari. The others Ferraris were around the 4 min 20 sec mark.[9]

The 2-litre Lotus 15 proved remarkably quick – Allison and debutante Graham Hill had the 4th and 5th fastest times in practice in a car virtually half the weight of the Ecosse Jaguars. In contrast the small works Lotus broke its new engine and had to switch to an FWC-spare.[13]

As a comparison, some of the lap-times recorded during practice were:[14][1]

| Class | Car | Driver(s) | Best Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| S-3000 | Aston Martin DBR1/300 #2 | Moss | 4min 07.3sec |

| S-2000 | Lotus 15 #26 | G. Hill | 4min 12.7sec |

| S-3000 | Jaguar D-Type #6 | Fairman | 4min 13sec |

| S-3000 | Ferrari 250 TR/58 #12 | Hawthorn | 4min 13sec |

| S-2000 | Porsche 718 RSK #29 | Behra | 4min 20.5sec[1] / 4min 29sec[14] |

| S-1500 | Porsche 718 RSK #31 | Barth | 4min 31sec |

| S-1100 | Lotus 11 #38 | Frost/Hicks | 5min 10sec |

| S-750 | OSCA 750S #42 | de Tomaso | 5min 19sec |

Race

Start

It was a hot and sunny afternoon when the French tricolour fell at 4 pm. The first driver away was Moss in his Aston Martin – as lightning-quick off the line as usual – chased by his teammate Brooks and the Jaguars and Ferraris. Just 4½ minutes after his standing start, Moss came past at the end of the first lap with a quarter-mile, five-second, lead on Hawthorn, Brooks, von Trips, Gendebien and the Aston of Salvadori. The best Jaguar was tenth.[15] At the end of the second lap, Sanderson brought in one of the Ecosse Jaguars with a broken piston. Five laps later, his teammate Fairman arrived with the same terminal problem.[7] The rapid Allison/Hill 2-litre Lotus, so fast in practise, had also retired after only three laps with a blown head-gasket.[16]

Moss was very fast – extending his lead by 3 seconds a lap over the pursuing Ferraris. Hawthorn, leading the pack, tried his hardest – setting the fastest lap of the race at 4min 08sec. After the first hour, Moss was leading Hawthorn by 26 sec. Then came von Trips, Brooks, Gendebien and Hamilton in his Jaguar, with only the first three on the lead lap.[17] Behra's uprated Porsche was leading the 2-litre class, running in 11th ahead of bigger Ferraris, Jaguars and Listers and well ahead of the rest of their class. Meanwhile, the two OSCAs were leading the S-750 class as well as the Index of Performance. The Ecosse Jaguars were gone – the team blaming the ‘official’ fuel for burning out the pistons[11] though it was traced to defective valvegear operation.[7]

Such was Moss's pace, all the competitors with exception of the first three leaders, had been lapped at least once. In the next hour Moss extended his lead to 95 seconds. Hawthorn tried to keep up, but his car was now suffering from a slipping clutch, with von Trips and Brooks rapidly closing in on him.[17] Then at 6.10pm just a lap before the first pit-stops were due, Moss stopped at the Mulsanne corner with a broken conrod.[12] Hawthorn went to the pits for an extended stop and it was the other works Ferraris – Hill ahead of von Trips – who took up the lead positions, ahead of Brooks’ Aston Martin and Hamilton's Jaguar.

Soon after, the weather (which was to dominate the rest of the race) suddenly changed as an enormous storm swept across the circuit, flooding the track and reducing the visibility to nil.[10][9] The track was soon awash and a terrible series of accidents began: between 6.30 and 10pm, no less than a dozen cars were involved in crashes. In the 3rd hour Maurice Charles lost control of his Jaguar in the downpour at Maison Blanche and was taken to hospital after being hit by two other cars.[7] In the 5th hour as a second downpour started, Stuart Lewis-Evans tangled the second Aston Martin with a back-marker at Dunlop Curve doing terminal damage.

But the worst happened in the twilight just after 10pm when Jean-Marie Brussin (racing under the pseudonym “Mary”) lost control of his Jaguar going into the sweeping Dunlop curve after the pits, hitting the earth bank, rolling and ending up near the crest of the rise. Unsighted, the next car on the scene was Bruce Kessler’s NART Ferrari, running 5th, who smashed into the Jaguar and burst into flames. Kessler was fortunate to be thrown clear, receiving only heavy bruising and broken ribs, but Brussin was killed in the accident.[18][17][19] Duncan Hamilton, running second at the time, was next to the scene but was alerted by an anonymous spectator throwing his hat onto the track – an action that Hamilton later considered possibly saved his life - by giving him just enough time to lift off and avoid the wrecked cars.[20]

Night

Hamilton was driving extremely well in the wet and soon after 10pm had his Jaguar up to second and within the hour had taken the lead after the next scheduled pit-stops. Phil Hill recalled the night-time driving: "The volume of rain was amazing but I discovered that if I sat on the tool roll to prop myself up – no, we didn’t use seatbelts – and then tilted my head back and looked just over the tip of the windshield and under the bottom of my visor, the view wasn’t too bad." He also keenly listened out for the sound of downshifting gears from cars ahead to get an idea of the approaching Mulsanne corner at the end of the long straight.[21][22][23]

Indeed, around 11.40pm von Trips (in the second-placed Ferrari) came to the high-speed Mulsanne kink and saw wreckage across the track and a driver lying unconscious on the road. Jean Hébert had been thrown clear when he rolled his Alfa Romeo avoiding a crashed car, and which had then caught fire. Von Trips stopped, ran back and pulled the Frenchman clear, as well as the biggest of the wreckage. When marshals ran up from the nearest post, he got back into his car and carried on his race. Hébert was not seriously injured.[24][25]

Another major accident then occurred at the Dunlop curve just before midnight. American Jay Chamberlain crashed his Lotus also avoiding a spinning car. He was lucky to be picked off the track before François Picard, in the Equipe Los Amigos Ferrari, crashed into it and destroying both cars, although both Chamberlain and Picard only received minor injuries. At 12.15am Wolfgang Seidel slipped his Ferrari, running 3rd, off at Arnage. Although only suffering light damage, it was well and truly stuck in the thick mud. Seidel was later reprimanded for not making more of an effort to dig out the car.[23] Hill, having taken over from Gendebien, drove exceptionally through the rain to catch and pass Hamilton's co-driver Ivor Bueb to go back into the lead. By 2.30am he had established a solid lap-and-a-half advantage.[26]

Hawthorn and Collins finally retired at 2am – having driven back up to 9th after falling as low as 18th with their clutch problems. NART's last Ferrari running – the 2-litre 500 TR of Rodriguez / Behra - retired just before half-time with a holed radiator.[27] At this point, there were just 26 cars left running, just half the field. The weather was not improving. Hill/Gendebien were still leading with Hamilton/Bueb a lap adrift. Now in third, some five laps behind the leader was the Aston Martin of Brooks/Trintignant, still going strong. The S-2000 Behra/Herrmann Porsche (proving very stable in the rain) had moved up to 4th overtaking the Whitehead brothers’ Aston Martin. The Halford/Taylor Lister was 6th with the Barth/ Frère Porsche in 7th leading the S-1500 class. Meanwhile, in the Index of Performance, it was a very close race between the works cars of de Tomaso's OSCA and Laureau's DB[17][9]

Morning

Soon after 6am Trintignant, who had been running a solid 3rd through the night, was stopped by a broken gearbox.[12][28] It ground to a halt at Mulsanne corner, where Moss had parked the sister car almost exactly twelve hours earlier.

Bruce Halford's Lister-Jaguar was running in 7th when it struck engine problems. Losing half an hour replacing the camshaft it then stopped on the Mulsanne straight. Watched by a crowd, and discreetly advised by his mechanic standing nearby, co-driver Brian Naylor spent over an hour repairing the gearbox on his own and bump-starting it again.[29]

Hamilton had been running a solid 2nd place all morning but it was another heavy thunderstorm around noon that led to his retirement. Coming into Arnage he was suddenly confronted with a stationary Panhard in the road. Taking avoiding action, he lost control and rolled the Jaguar which landed upside-down straddling a water-soaked ditch. Once again, he was lucky as two spectators were nearby, sheltering from the heavy rain, and could pull out the unconscious Hamilton before he drowned. He was taken to hospital with concussion, minor cuts and leg injuries.[20][9][4] Hamilton's accident had happened right in front of Hill and the Jaguar's demise left the Hill / Gendebien Ferrari with an enormous 10-lap lead over Whitehead's Aston Martin. The Porsche team had been having an outstanding race with the Behra / Herrmann 1.6L RSK up to 3rd despite, struggling with fading brakes. The 1.5L variant of Barth/Frère was a lap behind and the privateer Porsche of Carel de Beaufort in 5th.

Finish and post-race

.jpg.webp)

By mid-afternoon the rain finally ceased, so it was rather ironic that the race ended in sunshine on a drying track. Hill crossed the finish line at 4pm, ending one of the wettest and most difficult 24 Heures du Mans in history. Second step on the podium went to the private-entry Aston Martin of the Whitehead brothers. Porsche completed its best Le Mans to date with a remarkable 3-4-5 result with the S-2000 and S-1500 class victories after so many of the bigger-engined cars failed.

The OSCA of de Tomaso/Davis won the S-750 class, finishing 11th overall, having been chased hard throughout the race by the DB-Panhard of Laureau/Cornet, eventually finishing only 2 laps ahead of them. Three DBs finished, however only a single representative from Lotus, Stanguellini and Monopole got to the finish line in this largest class. In contrast, both OSCAs finished and claimed a 1-2 success in the Index of Performance, giving both major trophies to Italian cars. Alejandro de Tomaso subsequently founded his own supercar company in the next year, with his racing wife, Coca-Cola heiress, Elizabeth Isabel Haskell.[30][31] The new Tojeiro-AC eventually finished 8th, and second in S-2000 (the only other classified finisher in the class) but 31 laps behind the Porsche. Throughout Sunday Stoop and Bolton had battled loose handling, traced to the differential mountings gradually falling apart and had driven very cautiously in the bad weather. It managed to exactly meet its Index requirements with a ratio of 1.0, whereas the other AC, finishing 2 laps behind just missed out being classified. The Lister made it to the finish but its delays had also cost it too much time to be classified.[32][33]

This was Ferrari's third win, and coincidentally, the 1954 second victory had also been a contest in the rain versus Duncan Hamilton's Jaguar. This time however none of the Jaguars or works Aston Martins finished. Despite the atrocious weather for most of the race, the race distance of winners Gendebien and Hill would still have given them fifth place in the previous year's race. For the fourth consecutive race, Hawthorn was the quickest driver over a single lap, but his best lap of 4’ 08 was well down on his 3’ 58.7 record of 1957.[10] Sadly, this was the last Le Mans for the Ferrari works drivers: both Musso and Collins were killed in Grand Prix later in the year and, after retiring as the 1958 F1 World Champion, Hawthorn would also be killed within the next year.[34][35] In a grim year it also saw the death of Peter Whitehead, killed in an accident when his half-brother was driving in the Tour de France Automobile.[12]

Official results

Results taken from Quentin Spurring's book, officially licensed by the ACO[36] Class Winners are in Bold text.

| Pos | Class | No | Team | Drivers | Chassis | Engine | Laps |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | S3.0 | 14 | Ferrari 250 TR/58 | Ferrari 3.0L V12 | 305 | ||

| 2 | S3.0 | 5 | (private entrant) |

Aston Martin DB3S | Aston Martin 3.0L S6 | 293 | |

| 3 | S2.0 | 29 | Porsche 718 RSK | Porsche 1588cc F4 | 291 | ||

| 4 | S1.5 | 31 | Porsche 718 RSK | Porsche 1498cc F4 | 290 | ||

| 5 | S1.5 | 32 | Porsche 550A | Porsche 1498cc F4 | 288 | ||

| 6 | S3.0 | 21 | Ferrari 250 TR | Ferrari 3.0L V12 | 279 | ||

| 7 | S3.0 | 22 | (private entrant) |

Ferrari 250 TR | Ferrari 3.0L V12 | 278 | |

| 8 | S2.0 | 28 | AC Ace LM Prototype | Bristol 1971cc S6 | 257 | ||

| N/C * | S2.0 | 27 | AC Ace | Bristol 1971cc S6 | 255 | ||

| 9 | S1.5 | 34 | (private entrant) |

Porsche 550A | Porsche 1498cc F4 | 254 | |

| 10 | S750 | 42 | O.S.C.A. 750S | OSCA 749cc S4 | 252 | ||

| 11 | S750 | 44 | Deutsch et Bonnet |

D.B. HBR-4 Spyder | Panhard 745cc F2 | 250 | |

| 12 | S750 | 46 | Deutsch et Bonnet |

D.B. HBR-4 Spyder | Panhard 745cc F2 | 242 | |

| 13 | S750 | 41 | O.S.C.A. 750S | OSCA 749cc S4 | 241 | ||

| N/C * | S3.0 | 10 | (private entrant) |

Lister | Jaguar 3.0L I6 | 241 | |

| N/C * | S2.0 | 24 | Peerless GT Coupé | Triumph 1991cc S4 | 240 | ||

| 14 | S750 | 51 | Monopole X86 | Panhard 745cc F2 | 218 | ||

| 15 | S750 | 45 | Deutsch et Bonnet |

D.B. HBR-4 GTS Coupé | Panhard 745cc F2 | 214 | |

| 16 | S750 | 53 | Stanguellini S750 Sport | Fiat 741cc S4 | 212 | ||

| 17 | S750 | 55 | Lotus 11 | Coventry Climax FWC 741cc S4 |

202 |

- Note *: Not Classified because of Insufficient distance covered

Did Not Finish

| Pos | Class | No | Team | Drivers | Chassis | Engine | Laps | Reason |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNF | S3.0 | 8 | (private entrant) |

Jaguar D-Type | Jaguar 3.0L S6 | 251 | Accident (20hr) | |

| DNF | S3.0 | 3 | Aston Martin DBR1/300 | Aston Martin 3.0L S6 | 173 | Gearbox (15hr) | ||

| DNF | S1.1 | 38 | Lotus 11 | Coventry Climax FWA 1098cc S4 |

162 | Electrics (20hr) | ||

| DNF | S3.0 | 1 | (private entrant) |

Maserati 300 S | Maserati 3.0L S6 | 142 | Transmission (15hr) | |

| DNF | S750 | 47 | (private entrant) |

D.B. HBR-5 Coupé | Panhard 745cc F2 | 129 | Engine (14hr) | |

| DNF | S2.0 | 25 | Ferrari 500 TR | Ferrari 1998cc V12 | 119 | Overheating (12hr) | ||

| DNF | S3.0 | 12 | Ferrari 250 TR/58 | Ferrari 3.0L V12 | 112 | Clutch (11hr) | ||

| DNF | S750 | 54 | Stanguellini S750 Sport | Fiat 741cc S4 | 110 | Engine (14hr) | ||

| DNF | S3.0 | 16 | Ferrari 250 TR/58 | Ferrari 3.0L V12 | 101 | Accident (9hr) | ||

| DNF | S750 | 48 | Monopole X89 | Panhard 745cc F2 | 101 | Accident (12hr) | ||

| DNF | S1.1 | 40 | Tojeiro TCM | Coventry Climax FWA 1098cc S4 |

83 | Transmission (9hr) | ||

| DNF | S3.0 | 19 | Ferrari 250 TR | Ferrari 3.0L V12 | 77 | Electrics (8hr) | ||

| DNF | S3.0 | 20 | Ferrari 250 TR | Ferrari 3.0L V12 | 72 | Accident (7hr) | ||

| DNF | S3.0 | 18 | Ferrari 250 TR | Ferrari 3.0L V12 | 64 | Accident (7hr) | ||

| DNF | S1.5 | 37 | Alfa Romeo Giulietta SZ | Alfa Romeo 1290cc S4 | 59 | Accident (8hr) | ||

| DNF | S2.0 | 30 | Porsche 718 RSK | Porsche 1588cc F4 | 55 | Accident (9hr) | ||

| DNF | S3.0 | 4 | Aston Martin DBR1/300 | Aston Martin 3.0L S6 | 49 | Accident (5hr) | ||

| DNF | S3.0 | 11 | (private entrant) |

Jaguar D-Type | Jaguar 3.0L S6 | 47 | Fatal accident (7hr) | |

| DNF | S3.0 | 17 | (private entrant) |

Ferrari 250 TR | Ferrari 3.0L V12 | 45 | Engine (7hr) | |

| DNF | S750 | 50 | Monopole VM-S | Panhard 745cc F2 | 44 | Engine (10hr) | ||

| DNF | S3.0 | 9 | Lister | Jaguar 3.0L S6 | 43 | Engine (4hr) | ||

| DNF | S1.5 | 35 | Lotus 15 | Coventry Climax FPF 1476cc S4 |

39 | Accident (8hr) | ||

| DNF | S750 | 52 | Stanguellini 750 S | Fiat 741cc S4 | 38 | Accident (5hr) | ||

| DNF | S3.0 | 58 (reserve) |

Ferrari 250 TR | Ferrari 3.0L V12 | 33 | Accident (4hr) | ||

| DNF | S1.5 | 36 | Alfa Romeo Giulietta SVZ | Alfa Romeo 1290cc S4 | 31 | Fuel system (8hr) | ||

| DNF | S3.0 | 2 | Aston Martin DBR1/300 | Aston Martin 3.0L S6 | 30 | Engine (3hr) | ||

| DNF | S3.0 | 57 (reserve) |

(private entrant) |

Jaguar D-Type | Jaguar 3.0L S6 | 29 | Accident (3hr) | |

| DNF | S1.1 | 39 | Lotus 11 | Coventry Climax FWA 1098cc S4 |

28 | Accident (3hr) | ||

| DNF | S2.0 | 23 | (private entrant) |

Maserati 200 SI | Maserati 1994cc S4 | 20 | Gearbox (3hr) | |

| DNF | S750 | 56 | Lotus 15 | Coventry Climax FWMA 741cc S4 |

19 | Accident (4hr) | ||

| DNF | S750 | 49 | Monopole X86 | Panhard 745cc F2 | 10 | Engine (2hr) | ||

| DNF | S3.0 | 6 | Jaguar D-Type | Jaguar 3.0L S6 | 7 | Engine (1hr) | ||

| DNF | S2.0 | 26 | Lotus 15 | Coventry Climax FPF 1965cc S4 |

3 | Engine (1hr) | ||

| DNF | S3.0 | 7 | Jaguar D-Type | Jaguar 3.0L S6 | 2 | Engine (1hr) | ||

| DNF | S750 | 43 | V.P. Spyder | Renault 747cc S4 | 2 | Gearbox (1hr) |

Did Not Start

| Pos | Class | No | Team | Drivers | Chassis | Engine | Reason |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNS | S3.0 | 15 | (private entrant) |

Ferrari 250 TR | Ferrari 3.0L V12 | Withdrawn | |

| DNS | S1.5 | 33 | (private entrant) |

Porsche 550A | Porsche 1498cc F4 | Withdrawn | |

| DNS | S1.5 | 59 (reserve) |

(private entrant) |

Porsche 550A | Porsche 1498cc F4 | Reserve entry | |

| DNS | S750 | 60 (reserve) |

Stanguellini 750 S | Fiat 741cc S4 | Reserve entry | ||

| DNS | S750 | 61 (reserve) |

V.P. Sport | Renault 747cc S4 | Reserve entry | ||

| DNS | S750 | 62 (reserve) |

CTAP | Renault 747cc S4 | Reserve entry | ||

| DNS | S2.0 | 63 (reserve) |

Peerless GT Coupé | Triumph 1991cc S4 | Reserve entry |

Index of Performance

| Pos | Class | No | Team | Drivers | Chassis | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | S750 | 42 | O.S.C.A. 750S | 1.270 | ||

| 2 | S750 | 44 | Deutsch et Bonnet |

D.B. HBR-4 Spyder | 1.265 | |

| 3 | S750 | 46 | Deutsch et Bonnet |

D.B. HBR-4 Spyder | 1.225 | |

| 4 | S750 | 41 | O.S.C.A. 750S | 1.216 | ||

| 5 | S1.5 | 31 | Porsche 718 RSK | 1.191 | ||

| 6 | S1.5 | 32 | Porsche 550A | 1.183 | ||

| 7 | S2.0 | 29 | Porsche 718 RSK | 1.181 | ||

| 8 | S3.0 | 14 | Ferrari 250 TR/58 | 1.135 | ||

| 9 | S750 | 51 | Monopole X86 | 1.103 | ||

| 10 | S3.0 | 5 | (private entrant) |

Aston Martin DB3S | 1.089 |

- Note: Only the top ten positions are included in this set of standings. A score of 1.00 means meeting the minimum distance for the car, and a higher score is exceeding the nominal target distance.[37]

24th Rudge-Whitworth Biennial Cup (1957/1958)

There were no eligible finishers for the Biennial Cup.[38]

Statistics

Taken from Quentin Spurring's book, officially licensed by the ACO

- Fastest Lap in practice – Moss, #2 Aston Martin DBR1/300 – 4m 07.3s; 195.85 kp/h (121.70 mph)

- Fastest Lap: Hawthorn, #12 Ferrari 250 TR/58 - 4:08.0secs; 195.40 kp/h (121.42 mph)

- Distance - 4,101.93 km (2,548.82 mi)

- Winner's Average Speed - 170.91 km/h (106.20 mph)

- Attendance – 150 000[14]

Standings after the race

| Pos | Championship | Points |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 32 (38) | |

| 2 | 18 (19) | |

| 3 | 14 | |

| 4 | 3 | |

| 5 | 2 | |

Championship points were awarded for the first six places in each race in the order of 8-6-4-3-2-1. Manufacturers were only awarded points for their highest finishing car with no points awarded for additional cars finishing. Only the best 4 results out of the 6 races would be included for the final score. Total points earned, but not counted towards the championship, are given in brackets.

- Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Moity 1974, p.69

- 1 2 Spurring 2011, p.310

- ↑ Spurring 2011, p.308

- 1 2 "Le Mans 24 Hours 1958 - Racing Sports Cars".

- ↑ "Edição de 1958".

- 1 2 3 Clausager 1982, p100

- 1 2 3 4 Spurring 2011, p.322

- 1 2 "Le Mans 24 Hours 1958 - Entry List - Racing Sports Cars".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Le Mans 1958".

- 1 2 3 "Reference at www.sportscars.tv".

- 1 2 Laban 2001, p.125

- 1 2 3 4 Spurring 2011, p.317

- ↑ Spurring 2011, p.326

- 1 2 3 Clarke 2009, p.11: Road & Track Oct 1958

- ↑ Clarke 2009, p.12: Motor Jun25 1958

- ↑ Spurring 2011, p.327

- 1 2 3 4 Clarke 2009, p.12: Road & Track Oct 1958

- ↑ Spurring 2011, p.311

- ↑ Clarke 2009, p.19: Motor Jun25 1958

- 1 2 Spurring 2011, p.323

- ↑ Hill 2004, p.122

- ↑ Cannell 2011, p.173

- 1 2 Fox 1973, p.143

- ↑ Spurring 2011, p.325

- ↑ Cannell 2011, p.174

- ↑ Cannell 2011, p.176

- ↑ Spurring 2011, p.315

- ↑ Clarke 2009, p.21: Motor Jun25 1958

- ↑ Spurring 2011, p.329

- ↑ Spurring 2011, p.318

- ↑ "Reference at www.motorsportmagazine.com".

- ↑ "1958 le Mans 24 Hours". Archived from the original on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2015-12-26.

- ↑ "Reference at www.sportscars.tv".

- ↑ Spurring 2011, p.314

- ↑ Clausager 1982, p101

- ↑ Spurring 2011, p.2

- ↑ Clarke 1997, p.88

- ↑ Spurring 2011, p.335

References

- Spurring, Quentin (2011) Le Mans 1949-59 Sherborne, Dorset: Evro Publishing ISBN 978-1-84425-537-5

- Cannell, Michael (2011) The Limit London: Atlantic Books ISBN 978-184887-224-0

- Clarke, R.M. - editor (2009) Le Mans 'The Ferrari Years 1958-1965' Cobham, Surrey: Brooklands Books ISBN 1-85520-372-3

- Clausager, Anders (1982) Le Mans London: Arthur Barker Ltd ISBN 0-213-16846-4

- Fox, Charles (1973) The Great Racing Cars and Drivers London: Octopus Books Ltd

- Hill, Phil (2004) Ferrari: A Champion's View Deerfield: Dalton Watson Fine Books ISBN 978-185443-212-4

- Laban, Brian (2001) Le Mans 24 Hours London: Virgin Books ISBN 1-85227-971-0

- Moity, Christian (1974) The Le Mans 24 Hour Race 1949-1973 Radnor, Pennsylvania: Chilton Book Co ISBN 0-8019-6290-0

External links

- Racing Sports Cars – Le Mans 24 Hours 1958 entries, results, technical detail. Retrieved 13 February 2017

- Le Mans History – Le Mans History, hour-by-hour (incl. pictures, YouTube links). Retrieved 13 February 2017

- Sportscars.tv – race commentary. Retrieved 10 March 2017

- World Sports Racing Prototypes – results, reserve entries & chassis numbers. Retrieved 13 February 2017

- Unique Cars & Parts – results & reserve entries. Retrieved 10 March 2017

- Formula 2 – Le Mans 1958 results & reserve entries. Retrieved 13 February 2017

- YouTube English colour footage & engine sound (1½ mins). Retrieved 13 February 2017

- YouTube English b/w footage (3 mins). Retrieved 13 February 2017

- YouTube French colour footage (3 mins). Retrieved 13 February 2017

- YouTube German colour footage, looking at Porsche (3 mins). Retrieved 13 February 2017