Stadium Australia, the match venue | |||||||

| Event | 2003 Rugby World Cup | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| After extra time | |||||||

| Date | 22 November 2003 | ||||||

| Venue | Stadium Australia, Sydney | ||||||

| Man of the Match | Jonny Wilkinson (England) | ||||||

| Referee | André Watson (South Africa)[1] | ||||||

| Attendance | 82,957 | ||||||

| Weather | slightly wet | ||||||

The 2003 Rugby World Cup Final was the final match of the 2003 Rugby World Cup, the fifth edition of the Rugby World Cup competition organised by the International Rugby Board (IRB) for national rugby union teams. The match was played at Stadium Australia in Sydney on 22 November 2003, and was contested by Australia (the tournament hosts) and England. The 20-team competition consisted of a group stage, from which eight squads qualified for the knockout stage. En route to the final, Australia finished first in Pool A with four wins and no losses or draws before defeating Scotland in the quarter-final and New Zealand in the semi-final. England finished on top of Pool C and, like Australia, went undefeated with four victories and no draws before beating Wales in the quarter-final and France in the semi-final.

The final was played in front of a Rugby World Cup record crowd of 82,957, with 22 to 30 million television viewers, and was refereed by André Watson of South Africa. Australia scored first when Lote Tuqiri scored a try in the sixth minute, but Elton Flatley failed to score the resulting conversion. England's first points were through a penalty goal scored by Jonny Wilkinson at 11 minutes; Wilkinson scored a second penalty nine minutes later to put his side ahead of Australia. A third Wilkinson penalty goal after 28 minutes and a 38th-minute try by Jason Robinson (which Wilkinson was unable to convert) gave England a 14–5 lead at half-time. The second half saw Flatley score three penalty goals in succession; regular time ended with both teams tied 14–14, and the match went into extra time. Wilkinson scored a fourth penalty goal to put England back ahead of Australia in the second minute of extra time before Flatley equalised again with his fourth penalty goal with two minutes of extra time to play. With 28 seconds remaining, Wilkinson scored a drop goal with his right foot to secure a 20–17 victory for England.

England's win was their first Rugby World Cup title. They were the first Northern Hemisphere team to win the tournament, ending 16 years of dominance by Southern Hemisphere teams. They are currently the only Northern Hemisphere team to have won a Rugby World Cup title. Wilkinson was named man of the match, and the England playing and senior coaching team were appointed to the Order of the British Empire in the 2004 New Year Honours. England failed to defend their trophy at the following 2007 Rugby World Cup (hosted by France), losing 15–6 to South Africa in the final. Australia reached the tournament's quarter-final stage, where they were defeated by England.

Background

The 2003 Rugby World Cup, the fifth edition of the Rugby World Cup (the International Rugby Board's (IRB) leading quadrennial rugby union tournament for national teams), was held in Australia from 10 October to 22 November 2003.[lower-alpha 1][3][4] In the finals, 20 teams played a total of 48 matches.[4] The eight quarter-finalists in the 1999 Rugby World Cup automatically qualified for the tournament; the remaining twelve spots were decided in qualifying rounds played between 23 September 2000 and 27 April 2003 by teams from a record 81 nations.[2][5]

Teams were divided into four groups of five in the finals, with each team playing each other once in a round-robin format. The two top teams from each group advanced to a knockout stage.[4] Rights to host the final were awarded to Stadium Australia, a purpose-built venue for the 2000 Summer Olympics and the 2000 Summer Paralympics in Sydney Olympic Park (an urban renewal project in the mid-west suburb of Homebush Bay).[6] The stadium played host to six other matches in the World Cup.[7]

Australia had won the World Cup on two previous occasions, in 1991 and 1999. Although England had never won the tournament before, they reached the 1991 final (losing to Australia, 12–6).[3] The 2003 final was the 29th match between Australia and England.[8] Since Australia and England first played each other in 1909, England won 16 of those meetings (including the previous four), Australia won 11 and drew once, in November 1997.[9] The teams had played each other in three of the past four World Cups,[10] and the 2003 final was their fourth meeting in the competition's history.[8] The most recent match between them before the 2003 World Cup was played at Docklands Stadium in Melbourne on 21 June 2003, a 29–14 victory for England.[9] England had won 21 of their previous 22 test matches, and Australia had lost four matches before the competition began.[11] At the start of the tournament, England were ranked first in the inaugural IRB World Rugby Rankings; Australia were ranked fourth.[12]

Route to the final

Australia

| Opponent | Result | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Argentina | 24–8 |

| 2 | Romania | 90–8 |

| 3 | Namibia | 142–0 |

| 4 | Ireland | 17–16 |

| QF | Scotland | 33–16 |

| SF | New Zealand | 22–10 |

Australia qualified for the tournament as defending champions, and were drawn in Pool A with Argentina, Ireland, Namibia and Romania. Their first match, against Argentina on 10 October at Stadium Australia, was the tournament's opening game.[4] Australia led 11–0 after two Elton Flatley penalties and Wendell Sailor's try at 20 minutes which Flatley failed to convert. Felipe Contepomi scored Argentina's only penalty seven minutes later, before a third Flatley penalty put Australia ahead 13–3 at half-time. Flatley scored his final penalty to extend Australia's lead before Ignacio Corleto scored a 72nd-minute try. A Joe Roff try converted by Flatley two minutes later, however, gave Australia a 24–8 win.[13][14] Australia's second pool match was against Romania at Suncorp Stadium in Brisbane on 18 October.[4] They won 90–8, scoring three tries by Mat Rogers, two tries each by Matt Burke, Stephen Larkham and one try each by Flatley, Stirling Mortlock, Roff, Matt Giteau, Lote Tuqiri and George Smith; Flatley adding 11 conversions and a penalty. Romania's eight points came from a Petrișor Toderașc try and a Ionuț Tofan penalty. At 18 seconds, Flatley scored the earliest World Cup try.[15]

The team's third group fixture was against Namibia at Adelaide Oval on 25 October.[4] Australia won by a World Cup-record margin of 142–0, with a tournament-record 22 tries: five by Chris Latham, three each by Giteau and Tuqiri, two each by Rogers and Morgan Turinui and one each by David Lyons, Mortlock, Jeremy Paul, Nathan Grey, Matt Burke, John Roe. Rogers had one penalty try and 16 conversions.[lower-alpha 2][17] Australia concluded their pool matches against Ireland on 1 November at Melbourne's Docklands Stadium. George Gregan gave Australia the lead with a drop goal, followed with a try by Smith. Ronan O'Gara's penalty put Ireland five points behind before a Flatley penalty restored Australia's eight-point lead. A second penalty goal by O'Gara gave Australia an 11–6 lead at half-time. Four minutes into the second half, Flatley scored a second penalty before a Brian O'Driscoll try (converted by O'Gara) put Ireland one point behind. Australia went four points ahead after Flatley's third penalty and, despite an O'Driscoll drop goal, advanced to the quarter-finals 17–16 as pool winners.[18]

Their quarter-final was against Scotland at Brisbane's Suncorp Stadium on 8 November.[4] The sides were tied 9–9 at half-time, after three penalties by Flatley and two penalties and a drop goal by Chris Paterson. Tries by Mortlock, Gregan and Lyons were converted by Flatley, who scored his fourth penalty in the second half to put Australia 24 points ahead of Scotland. A last-minute Robbie Russell try (converted by Paterson) gave Scotland seven extra points, but Australia won the match 33–16 for a place in the semi-final.[19] They returned to Sydney's Stadium Australia to play New Zealand in their semi-final on 15 November. Australia opened the scoring at nine minutes, when Mortlock scored a try which Flatley converted. Flatley scored two penalties to increase Australia's lead before a try by New Zealand's Reuben Thorne, converted by Leon MacDonald, cut Australia's lead to 13–7 at half-time. Flatley scored three more penalties in the second half and, although MacDonald scored a late penalty for New Zealand, Australia held on to win the match 22–10 and a berth in the final.[20]

England

| Opponent | Result | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Georgia | 84–6 |

| 2 | South Africa | 25–6 |

| 3 | Samoa | 35–22 |

| 4 | Uruguay | 111–13 |

| QF | Wales | 28–17 |

| SF | France | 24–7 |

England qualified for the finals by reaching the quarter-finals of the 1999 World Cup, and were placed in Pool C with Georgia, Samoa, South Africa and Uruguay. Their finals campaign began on 12 October at Subiaco Oval in Perth against Georgia.[4] The team secured a 84–6 victory with one try each by Mike Tindall, Matt Dawson, Steve Thompson, Neil Back, Lawrence Dallaglio, Mark Regan, Dan Luger and Jason Robinson, two tries by Will Greenwood and Ben Cohen, and conversions by Jonny Wilkinson and Paul Grayson; Wilkinson added two penalties. Georgia's six points were penalties by Malkhaz Urjukashvili and Paliko Jimsheladze.[21] Six days later, England played South Africa at Subiaco Oval.[22] The teams were tied 6–6 at half-time, with two Louis Koen penalties for South Africa and two penalties by England's Wilkinson. Two more penalties by Wilkinson followed, before he converted a Greenwood try and scored two drop goals to put England at the top of their pool with a 25–6 win.[23]

Their third group game was against Samoa at Docklands Stadium in Melbourne on 26 October.[4] Samoa went ten points ahead with a penalty and a converted try by Earl Va'a before England levelled with a Neil Back try (converted by Wilkinson), after which Wilkinson scored a penalty. Two more penalties by Va'a and a second penalty by Wilkinson gave Samoa a 16–13 lead at half-time. England earned a penalty try after Samoa conceded a scrum, and Wilkinson converted it to return England to the lead. Va'a's two subsequent penalties put Samoa back in the lead, but England won 35–22 with tries by Wilkinson, Iain Balshaw and Vickery; Wilkinson converted a second try.[24] England's final group match was against Uruguay at Brisbane's Suncorp Stadium on 2 November. They had a team World Cup record victory of 111–13, with a national-record-equalling 17 tries scored by Lewis Moody, Josh Lewsey, Balshaw, Andy Gomarsall, Luger, Grayson, Stuart Abbott and Robinson (converted by Grayson or Mike Catt) to qualify for the quarter-finals as pool winners. Uruguay's points came from two first-half Juan Menchaca penalties and a second-half Pablo Lemoine try converted by Menchaca.[25]

In the quarter-finals, England faced Wales at Suncorp Stadium on 9 November.[26] England scored the game's first points with a Wilkinson penalty, but Wales led 10–3 at half-time after tries by Stephen Jones and Colin Charvis (which Jones failed to convert). England moved 15 points ahead of Wales with a Greenwood try (converted by Wilkinson), followed by five successive penalties by Wilkinson. Martyn Williams scored a try (converted by Iestyn Harris) to put Wales eight points behind before a last-minute Wilkinson drop goal advanced England to the semi-finals, 28–17.[27] England then faced France in the semi-finals in wet, cold conditions at Stadium Australia on 16 November. Wilkinson gave England the lead with a ninth-minute penalty before an England line-out error allowed Serge Betsen to score a try, converted by Frédéric Michalak to give France a 7–3 advantage. England retook the lead when Wilkinson scored two drop goals and two penalties to give them a 12–7 lead at half-time. In the second half, Wilkinson scored a second drop goal and three more penalties to put England through to the final with a 24–7 victory.[28]

Match

Before the match

André Watson, a 45-year-old retired civil engineer and school rugby fly-half from South Africa, was selected as referee for the final.[29] Watson had refereed two 2003 World Cup matches: the New Zealand–Wales and Argentina–Ireland matches in the group stage.[30] He also refereed the 1999 Rugby World Cup Final and a number of Currie Cup and Super 12 finals.[29] Watson was assisted by Paddy O'Brien and Paul Honiss of New Zealand, the two touch judges. Joël Jutge and Alain Rolland of France and Ireland were named the fourth and fifth officials, respectively, and South Africa's Jonathan Kaplan was the television match official.[1] Tickets for the final sold out on 22 August 2003.[31] The IRB returned an additional 2,000 tickets for the match to the Australian Rugby Union which it sold to the public since 13 November.[32] Several Australian and British bookmakers cited England as the favourite to win the match.[33][34]

Australia coach Eddie Jones noted that World Cup finals were generally disorganised, and said that it would be good if the match was contested "with a good balance between the important ingredients of rugby, and that is contest versus continuity": "Our responsibility is to play naturally and with freedom and our natural game is to attack, so we'll be keeping our part of the bargain. If we can get England to, and the referee to contribute, we should have a great spectacle. It could be the world's great game of rugby."[11] England coach Clive Woodward was pleased with Australia for their organisation of the tournament and the quality of their players and said about his team's chances for the final, "My only goal when I left my business to take his job six years ago was to make England the best team in the world and win this thing. Now we have a real chance of doing exactly that."[35] Woodward added, "When the tournament began, I would have said this was my dream final. We have one objective and we're now one game away from achieving it. We certainly haven't come out here to finish second."[35]

A closing ceremony was held before the match. It began with the release of 18 of 20 inflatable cylindrical figures (representing the 20 qualifying teams), placed in a circle outside the pitch.[36] Kate Ceberano performed Cyndi Lauper's "True Colors", the competition's official song, replacing Kasey Chambers, who had withdrawn.[37][38] Three young children from the Sydney Children's Choir sang the rugby anthem, "World in Union", as part of the Rugby World Choir.[39] The Australian national anthem, "Advance Australia Fair", was performed by Alice Girle and performing-arts student Akos Miszlai[40] before the English national anthem "God Save the Queen" was played by Rugby World Choir members Belinda Evans and James Laing.[36]

The match was broadcast live on television by the Seven Network in Australia,[41] Sportsnet in Canada,[42] and on ITV1 and S4C in the United Kingdom.[43] The Theatre Broadcasting System of the Department of Defence carried coverage of the final for Australian troops stationed in Baghdad.[44] Radio coverage was by ABC Radio on the non-commercial programme ABC Radio Grandstand and the commercial Macquarie Network in Australia and by BBC Radio 5 Live in the United Kingdom.[45][46] Live sites were set up across Australia and London, with large screens to enable the public to watch the final.[47] Australian Foreign Minister Alexander Downer cautioned Australian citizens watching the final abroad to be mindful of their safety after the Istanbul bombings in Turkey.[48] The New South Wales Police adjusted its security measures to stop pitch invasions by spectators during the final.[49] The British government was represented at the match by Culture Secretary Tessa Jowell.[50]

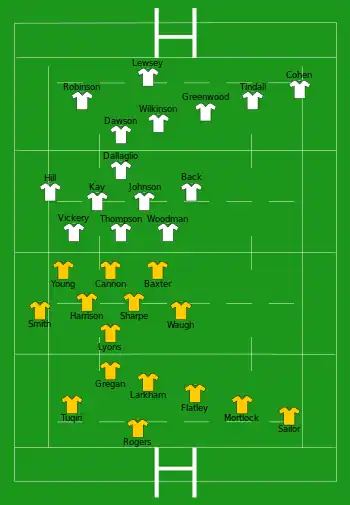

Both teams' coaches released their line-ups on 19 November.[51] Australia were without prop Ben Darwin, who sustained a prolapsed disc in his neck (contacting his spinal cord) during a scrum in the team's semi-final with New Zealand.[52] Coach Eddie Jones replaced Darwin with Al Baxter at the tight head prop position.[51] Jones also made Matt Dunning a prop reserve, and utility back Giteau replaced Grey as a substitute after Giteau's recovery from an ankle injury in Australia's quarter-final with Scotland.[53] England coach Clive Woodward made one change to the side which began their semi-final against France; Tindall replaced Catt (who was made a substitute) to counter Mortlock's running ability, and indicating that England wanted to run more with the ball, and not rely on Catt and Wilkinson's dual kicking strategy.[51] The final was the last time that captain Martin Johnson and Back represented England; both players retired the following year.[54]

First half

Low cloud cover and sporadic downpours fell in Sydney on the morning of the match; it tapered off to a drizzle,[35] making the pitch damp.[55] The match began before a World Cup record crowd of 82,957[36] at 20:00 local time with Wilkinson kicking the ball into Australia's right-hand defence, where it was collected by Nathan Sharpe.[56][57] At two minutes, Rogers threw to Tuqiri; it threatened to overlap, but went into touch.[57][58] A touch judge noticed that Woodman's right fist went outside at the back of a maul, and he was reprimanded by Watson.[55][59] A penalty on England's 10-yard (9.1 m) line was awarded to Australia,[56] but the team decided that it was too far for their players and Rogers should kick into touch. Australia earned a free kick when England had too many players in a line-out, but opted for a scrum.[55][57] Gregan passed the ball to Larkham, whose high shot was directed from right to left.[35][55] The taller Tuqiri out-jumped Robinson,[36][60] and gathered the ball to score a try in the corner after a short run. Flatley's attempt to convert the try from the right-hand touchline struck the inside of the left-hand post, preserving Australia's 5–0 lead.[35][55][56] Robinson passed some Australian players;[55] Lyons committed an infraction in a tackle, earning England a penalty kick.[58] Wilkinson made it 5–3 after 11 minutes, scoring the penalty from 47 m (154 ft).[59] Australia got a penalty kick two minutes later when Back held the ball too long in a line-out.[57][58] England gained possession with breaks by Lewsey, but both teams had difficulty handing the ball and were cautioned by Watson.[55]

At 20 minutes, England got a penalty kick when Cohen was tackled by Larkham without the ball.[56][57] Larkham sustained a lip injury for which he received medical attention, and Giteau was brought in as a blood replacement.[56][60] Wilkinson scored the penalty from outside the Australia half to put England ahead, 6–5.[56][57] At 23 minutes, Wilkinson's long drop-goal attempt with his left foot went wide.[57][59] Two minutes later, Ben Kay gathered the ball after Richard Hill kicked it through Australia's defence when Giteau dropped it after a Wilkinson tackle; Kay failed to score a try when he was tackled.[59][61] Wilkinson sustained a minor shoulder injury when he tackled Giteau.[61] In the 28th minute, England got another penalty kick after they won a scrum after a Flatley tackle and moved up the pitch.[55][56] Wilkinson scored a third penalty goal from a narrow angle to extend England's lead to four points.[57][59] Woodman was penalised two minutes later for incorrectly binding during a scrum, earning Australia a penalty.[57] Flatley failed to score the penalty goal from the left of England's 10-metre (33 ft) line.[56] Larkham returned to the pitch after 31 minutes, following medical treatment of his lip.[57] Dallaglio passed Australia's mid-pitch defence seven minutes later and passed the ball to Wilkinson,[62] who briefly ran with it before making a long pass to the approaching Robinson on his left.[2][55][56] Robinson passed Sailor, scoring a left-corner try.[36][61] Wilkinson failed to convert the try almost from the touchline, and the first half ended with England leading 14–5.[55]

Second half

Flatley began the second half of the match by kicking deep into the England half,[56] and England started making errors in a scrum or a line-out.[62] Seven minutes later, England made two errors in succession from consecutive line-outs and Australia earned a penalty kick when Dallaglio was penalised for being offside when he thought it was open play; Watson, however, decided that a ruck was being formed.[55][57][58] Flatley successfully scored the penalty from inside Australia's half to put Australia three points behind.[56] Soon afterwards, Australia made a change when David Giffin came on in place of Sharpe.[57] In the 53rd minute, Dawson and Lewsey made an illegal cross that caused an accidental obstruction and gave Australia a penalty kick inside the England 10-metre (33 ft) line.[56][59] Flatley kicked for goal from where he could score a try, but failed to score the penalty.[35] After 56 minutes, Australia substituted Larkham for Giteau.[57][59] The team made a double substitution one minute later, bringing on Paul for Brendan Cannon and Matt Cockbain for Lyons. At 58 minutes, Australia earned a penalty after Vickery incorrectly bound in a scrum; Rogers failed to score the goal. The rain began to increase in intensity, and both sides made more playing errors.[58]

In the 61st minute, Vickery was informed that he had illegally handled the ball on the floor in a ruck, giving Australia a penalty kick.[55][56][57] Flatley took the penalty in front of the posts from the 10-metre (33 ft) line, scoring to put Australia three points behind England.[56][62] Watson then called England for three consecutive infractions during scrums.[35] A shot by Tindall spun to the right at 68 minutes, and Greenwood gathered the ball.[56] Greenwood was prevented from scoring a try by a left-footed leg tackle from Rogers,[57][59] which brought the ball into touch just before the try line.[61] After 71 minutes, Australia substituted Roff for Sailor.[57] After England secured a line-out one minute later, Lewsey got the ball and passed it to Wilkinson[56] (whose second attempt to score a drop goal went wide of the left-hand post).[55][58] In the 79th minute, Catt was brought on for the injured Tindall.[56][57] With 90 seconds of regular time remaining,[2] Watson penalised England for collapsing a scrum and Woodman's failure to engage on their 22-metre (72 ft) line on the right side of the pitch; Woodman felt that Australia engaged too early, but a penalty kick was awarded to Australia.[55][36] Flatley scored the penalty from 15 m (49 ft) out on the right of the England half with ten seconds left, bringing on extra time with the teams tied 14–14.[60][62]

Extra time

One minute into extra time, England substituted Vickery for Leonard. England were awarded a penalty kick a minute later, when a line-out Johnson was pulled down by Justin Harrison.[56][57] Wilkinson opted to take the penalty,[57] and kicked a shot from 44 m (144 ft) out wide on the right which went between the posts and put England back in the lead.[55][62] Larkham came off the pitch again for Giteau because he was still bleeding, and an injured-looking Lewsey came off for Balshaw. Catt unsuccessfully attempted to score a drop goal on 89 minutes because Phil Waugh stopped him with a knock-on.[57] Wilkinson also tried to score a drop goal a minute later, but his shot went wide.[57][59] This ended the first half of extra time, with England leading Australia 17–14.[61]

At 92 minutes, Australia replaced Young with Dunning; England substituted Moody for Hill, who had a cramp, one minute later.[56][57] Tuqiri was prevented from scoring a try when Cohen and Robinson were tackled from 5 m (16 ft) three minutes later;[59][62] Wilkinson held the ball, giving Australia a line-out.[57] England got a penalty line-out in the 96th minute when Rogers held onto the ball during a tackle.[57][58] Dallaglio was penalised from coming in on the side and handling the ball in a ruck, giving Australia a penalty kick at 97 minutes.[55][57] Flatley scored the penalty from outside the England area to level the score 17–17 and, potentially, require a match-ending penalty shootout.[56][59] With more than one minute remaining, England won a line-out and moved towards Australia's area three times, including a dummy and run by Dawson that broke the line and brought England within drop goal range.[2] Dawson passed the ball to Wilkinson,[36] who could not be stopped by Gregan and scored a right-foot drop goal from 30 m (98 ft) out with 28 seconds left to put England back in the lead.[55][59][62] No further points were scored; Watson blew the final whistle, with England winning the match 20–17 for their first Rugby World Cup.[35]

Details

| 22 November 2003 20:00 AEDT (UTC+11) |

| Australia | 17–20 (a.e.t.) | |

| Try: Tuqiri 6' m Pen: Flatley 47', 61', 80', 97' | Report | Try: Robinson 38' m Pen: Wilkinson 11', 20', 28', 82' Drop: Wilkinson 100' |

| Stadium Australia, Sydney Attendance: 82,957[1] Referee: André Watson (South Africa)[1] |

Australia

|

England

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Man of the Match:[64]

|

Match rules[43]

|

Statistics

| Statistic | Australia | England |

|---|---|---|

| Tries | 1 | 1 |

| Conversions | 0 | 0 |

| Penalties | 4 | 4 |

| Dropped goals | 0 | 1 |

| Scrums | 12 | 9 |

| Possession | 42% | 58% |

| Territory | 46% | 54% |

| Yellow cards | 0 | 0 |

| Red cards | 0 | 0 |

Aftermath

England was the first Northern Hemisphere nation to win the Rugby World Cup, ending 16 years of Southern Hemisphere dominance.[35] IRB chairman Syd Millar presented the runner-up medals to the Australian side. The victorious England team received their medals from Australian Prime Minister John Howard before Johnson held up the Webb Ellis Cup presented to him by Howard.[66] The England team then took a lap of honour around the stadium.[35] Wilkinson was named man of the match and won the BBC Sports Personality of the Year Award.[64][67] Every member of England's playing and senior coaching staff was appointed at least a Member of Order of the British Empire in the 2004 New Year Honours.[68] In May 2004, the England squad received the Laureus World Sports Award for Team of the Year and Woodward was knighted.[69]

According to Woodward, the victory was "very important and it is just a big thank you to the Premiership clubs and the Rugby Football Union. We have just put the icing on the cake and we want to keep this going."[70] His counterpart, Jones, conceded that the better side won the final:[35] "You slug it out for 100 minutes and get beaten in the 99th – yeah, that would qualify as a photo finish. England were outstanding and are the best team in the world by one minute."[70] Wilkinson explained why he scored a drop final in the last minute of the match: "I didn't want the game to go to a drop-goal competition. I just wanted to win so much for the other guys. I had to make sure I hit the target when the chance came my way."[35] In a 2019 interview with BBC Sport, he described the goal as "not a memory that I treasure because I don't have much memory of it – but just an experience which gave me a glimpse of life a little bit outside the boundaries of what I thought was possible – something bigger."[71] Cannon described the drop goal as "like witnessing a car accident, you know it's about to happen but you don't want it to happen."[72]

Dawson said the win was "very surreal" after England's comeback from elimination in the quarter-final stage of the 1999 tournament.[35] Greenwood said that during the match and when he received his World Cup winners medal he thought about his son, Freddie, who died shortly after he was born in 2002.[73] Gregan said that although the Australian team were disappointed, they had "a good deal of pride there as well. It was a gutsy effort, coming down to the last play of the game. My team didn't leave anything out so I couldn't ask for anything more."[74] Injured prop Darwin said that he was frustrated to be unable to play in the final.[72] Flatley described the pressure he felt when scoring the two penalty goals which meant that the match would go into extra time: "I had my hands together praying and I didn't see either kick. I had my eyes closed. It was scary pressure. There wasn't a great deal going on in my head ... I just had to knock them over."[75] Although Rogers blamed himself for the loss because he had been unable to clear the ball in the final minute, Flatley told him that he was not to blame: "A million things go on and in a game like that you can't really put it down to one thing. "It wasn't like I was about to slit my wrists or anything, but I was hoping to kick it up a bit further and make it even harder for them to score."[76]

Watson's refereeing was criticised by the media and rugby-world figures.[55][77] Woodward's assistant Andy Robinson asked Watson during the post-match celebrations why England were penalised for scrum infringements, and was told to review the video footage.[77][78] Watson defended his decisions: "I was satisfied with my handling of the match and that includes the scrum infringements .... I ref what I see and nothing else and I was happy with my performance. If there were any problems, they will have been noted by the IRB and I have not had any comebacks from them."[78]

The team left Sydney on the evening of 24 November, and arrived at Heathrow Airport (greeted by 8,000 to 10,000 people) early the next morning.[68] Johnson, holding the trophy, was the first player to appear, and "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot" was sung.[79] A national day of celebration was organised by the Rugby Football Union on 8 December, and was seen by almost a million people.[68] The team paraded in open-top buses from Marble Arch to Trafalgar Square.[68] Ken Livingstone, the Mayor of London, awarded the squad the freedom of Greater London. The team then met the queen and other senior royal family members at Buckingham Palace, followed by a reception at 10 Downing Street with Prime Minister Tony Blair.[80]

The match viewership on ITV1 peaked overnight at around 14.5 million (82 percent of the British viewership) between 11:20 and 11:25 am and averaged 12.3 million (a 77 per cent viewing share);[81] it had a final peak rating of 15 million viewers. This was the highest viewership in the United Kingdom of a rugby union match since the 1991 Rugby World Cup Final was watched by an average of 13.6 million.[82] The Seven Network's coverage of the final had a nationwide average of four million viewers in Australia and peaked at a total of 4.3 million viewers, making it the most-watched football game in the history of Australian television.[83] Global audience figures for the 2003 Rugby World Cup final totalled between 22 and 30 million.[36][82]

At the next World Cup, hosted by France in 2007, England reached the final for the third time in tournament history before they were defeated by South Africa 15–6. Australia advanced from their group as winners before they were knocked out in the quarter-final stage by England.[84]

See also

Notes and references

Notes

- ↑ New Zealand were due to co-host the tournament, but the IRB forced the nation to withdraw in April 2002 over a disagreement about ground-signage rights.[2]

- ↑ As of 2021, this is the only occasion in which Australia have scored 100 points in one game, and it is Namibia's most significant loss.[16]

- ↑ Will Greenwood, for superstitious reasons, prefers to play wearing the number 13 shirt, even when selected to play inside centre.[63]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Jenkins, Graham (22 November 2003). "England clinch World Cup crown". Scrum.com. Archived from the original on 13 January 2004. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Welch 2007, pp. 70–73

- 1 2 Tikkanen, Amy; Augustyn, Adam; Levy, Michael; Ray, Michael; Luebering, J. E.; Lotha, Gloria; Young, Grace; Shepherd, Melinda C.; Sinha, Surabhi; Rodriguez, Emily (8 November 2015). "Rugby Union World Cup". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 9 November 2021. Retrieved 11 December 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Peatey 2011, pp. 146, 148–150, 323–348

- ↑ "A record 80 nations involved in RWC qualifiers". International Rugby Board. Archived from the original on 7 May 2006. Retrieved 11 December 2021."Final two places decided for Rugby World Cup 2003". International Rugby Board. Archived from the original on 26 February 2004. Retrieved 11 December 2021.

- ↑ Searle, Glen (September 2012). "The long-term urban impacts of the Sydney Olympic Games". Australian Planner. 49 (3): 195–202. doi:10.1080/07293682.2012.706960. S2CID 110259887. Archived from the original on 6 February 2022. Retrieved 11 December 2021 – via ResearchGate.

- ↑ "Stadium Australia: Sydney, New South Wales". ESPNscrum. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 11 December 2021.

- 1 2 "England set for Aussie showdown". BBC Sport. 21 November 2003. Archived from the original on 8 November 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- 1 2 Griffiths, John (21 November 2003). "Rugby World Cup 2003 Final: Head to Head Record". Scrum.com. Archived from the original on 28 November 2003. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ↑ Grace, Ben (19 November 2003). "Australia v England: Match preview". International Rugby Board. Archived from the original on 1 May 2005. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- 1 2 Pye, John (21 November 2003). "Rugby final promises to be 'great spectacle'". Brantford Expositor. p. B6. Archived from the original on 6 February 2022. Retrieved 10 November 2021 – via ProQuest.

- ↑ "England top rugby world rankings". CNN. 11 September 2003. Archived from the original on 9 November 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ↑ Thornley, Gerry (11 October 2003). "Hosts serve up nice starter". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 6 February 2022. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ↑ Harris, Bret (11 October 2003). "Tough for Wallabies". Herald Sun. p. 037. Archived from the original on 6 February 2022. Retrieved 18 December 2021 – via Gale OneFile: News.

- ↑ Growden, Greg (19 October 2003). "Wallabies Bust Records but the Riddles Remain Rugby Union World Cup Full-time Australia 90 D Romania 8". Sunday Age. p. 8. ProQuest 367389295. Archived from the original on 24 December 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2021 – via ProQuest.

- ↑ Hawkes 2015, pp. 50, 72

- ↑ Phillips, Mitch (26 October 2003). "Australia's embarrassing records". The Observer. Archived from the original on 9 November 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2021.Corrigan, James (26 October 2003). "Latham's leading role in theatre of the absurd". The Independent on Sunday. Archived from the original on 18 December 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ↑ Clark 2015, pp. 117–120, 141

- ↑ "Blacks should handle Aussies". Sunday Star-Times. 9 November 2003. p. B7. ProQuest 314016776. Retrieved 18 December 2021 – via ProQuest.

- ↑ Clark 2015, pp. 141–143

- ↑ Team England Rugby 2003, pp. 49, 57–59

- ↑ Team England Rugby 2003, p. 61

- ↑ Clark 2015, pp. 130–132

- ↑ Team England Rugby 2003, pp. 74–75, 82–85

- ↑ Team England Rugby 2003, pp. 87, 94–97

- ↑ Team England Rugby 2003, p. 99

- ↑ Clark 2015, pp. 138–140

- ↑ Team England Rugby 2003, pp. 113–114, 122–126

- 1 2 Averis, Mike (18 November 2003). "Watson earns his second final". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 November 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ↑ "Watson to referee World Cup final". ABC News. 17 November 2003. Archived from the original on 20 December 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2021.

- ↑ "World Cup Final sold out". ESPNscrum. 22 August 2003. Archived from the original on 19 December 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ↑ "Last chance to get to the big games – World Cup: 2 days to the All Blacks showdown". The Daily Telegraph. 13 November 2003. p. 013. Archived from the original on 24 December 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021 – via Gale OneFile: News.

- ↑ Riddle, Geoffrey (18 November 2003). "Rugby World Cup: Punters go for England". Racing Post. Archived from the original on 20 December 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2021 – via TheFreeLibrary.com.

Woods, Graham (22 November 2003). "Rugby World Cup: Punters put their shirts on England". Racing Post. p. 128. Archived from the original on 24 December 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2021 – via Gale OneFile: News.

Woolcock, Nicola (21 November 2003). "Breakfast of champions". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 20 December 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2021. - ↑ Kershler, Ray (21 November 2003). "Pommie plunge". The Daily Telegraph. p. 92. ProQuest 359025450. Archived from the original on 24 December 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2021 – via ProQuest.

Kogoy, Peter (21 November 2003). "Big bets are on England to win – Rugby: Bringing you the 2003 World Cup Final". The Australian. p. 33. ProQuest 357652818. Archived from the original on 24 December 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2021 – via ProQuest.

"Hard work will win Cup". Illawarra Mercury. 22 November 2003. p. 88. Archived from the original on 24 December 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2021 – via Gale OneFile: News. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Team England Rugby 2003, pp. 127–130, 137–144

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Jones 2004, pp. 219–227, 238

- ↑ Ceberano & Gilling 2014, p. 236

- ↑ "Ceberano gets a guernsey". The Mercury. 22 November 2003. p. 007. Archived from the original on 24 December 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021 – via Gale OneFile: News.

- ↑ "The final performance". International Rugby Board. 18 November 2003. Archived from the original on 3 May 2005. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ↑ Dennis, Anthony (19 August 2003). "The duo who'll sing for Wallabies – just don't ask about the rules". The Sydney Morning Herald. p. 3. ProQuest 363927170. Archived from the original on 24 December 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2021 – via ProQuest.

- ↑ Munro, Peter (22 November 2003). "All eyes now turn to the prize World Cup Special". The Sydney Morning Herald. p. 3. ProQuest 363999944. Archived from the original on 24 December 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021 – via ProQuest.

- ↑ "On TV". The Globe and Mail. 21 November 2003. p. S7. ProQuest 383937055. Archived from the original on 24 December 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2021 – via ProQuest.

- 1 2 "Rugby World Cup Final 2003: Rules". The Independent. 22 November 2003. p. 3. Archived from the original on 24 December 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021 – via ProQuest.

- ↑ Hart, Cath (22 November 2003). "Fans tune in around the globe". The Courier-Mail. p. 12. ProQuest 354265309. Archived from the original on 24 December 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2021 – via ProQuest.

- ↑ "Rugby World Cup radio coverage". Radioinfo. 6 October 2003. Archived from the original on 10 November 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ↑ "Your armchair guide to the two teams". The Guardian. 21 November 2003. p. 8. Archived from the original on 20 December 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2021 – via Newspapers.com

.

. - ↑ "Get behind the boys with songs of praise; Come on England". London Evening Standard. 20 November 2003. p. 6. ProQuest 329587894. Archived from the original on 24 December 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021 – via ProQuest."Where To Party Tonight – Rugby: Bringing you the 2003 World Cup Final". The Weekend Australian. 22 November 2003. p. 2. ProQuest 356539467. Archived from the original on 24 December 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021 – via ProQuest.

- ↑ "Downer issues World Cup warning". ABC News. 21 November 2003. Archived from the original on 10 November 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ↑ "Police ready for pitch invaders". The Newcastle Herald. Australian Associated Press. 22 November 2003. p. 123. ProQuest 365097456. Archived from the original on 24 December 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2021 – via ProQuest.

- ↑ "Blair sends support". BBC Sport. 21 November 2003. Archived from the original on 9 November 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- 1 2 3 Team England Rugby 2003, pp. 129–130

- ↑ Peatey 2011, p. 171

- ↑ "Baxter in for Darwin". The Sydney Morning Herald. 20 November 2003. Archived from the original on 19 December 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ↑ Stephens, John (31 October 2013). "2003 Rugby World Cup winners: where are they now? – in pictures". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 19 December 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Clark 2015, pp. 145–148

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 "Australia 17–20 England". Scrum.com. 22 November 2003. Archived from the original on 29 December 2003. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 "Clockwatch: Australia 17–20 England". BBC Sport. 22 November 2003. Archived from the original on 23 December 2005. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Jones, Dan (22 November 2003). "England 20 – 17 Australia". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 November 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Lemke, Gary (23 November 2003). "Timetable of a triumph: how the cup was won and lost". The Independent on Sunday. p. 2. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2021 – via Newspapers.com

.

. - 1 2 3 Smith 2015, pp. 177–179

- 1 2 3 4 5 "It's England's Cup". International Rugby Board. 22 November 2003. Archived from the original on 1 May 2005. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Mills, Simon (22 November 2003). "Wilkinson drop-goal makes England world champions at last". Rugby Football Union. Archived from the original on 4 March 2004. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ↑ "Greenwood sticks with lucky 13 despite move inside". ESPNscrum. New Zealand Press Association. 7 July 2005. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- 1 2 Mitchell, Kevin (23 November 2003). "Rugby Union: World Cup Final: Man of the Match". The Observer. p. 2. Archived from the original on 22 December 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2021 – via Newspapers.com

.

. - ↑ "Match Stats". International Rugby Board. Archived from the original on 14 October 2004. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ↑ Crabb, Annabel (25 November 2003). "PM makes amends with rugby praise". The Age. p. 4. ProQuest 363653783. Retrieved 22 December 2021 – via ProQuest.

- ↑ Bierley, Stephen (15 December 2003). "Jonny the drop-kick wins it for rugby". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 December 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 Jones 2004, pp. 239–240

- ↑ "Sports Awards: England's World Cup winners Team of the Year". The Independent. 10 May 2004. Archived from the original on 24 October 2017. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- 1 2 "We have just put the icing on the cake' – What They Said". The Observer. 23 November 2003. p. 5. Archived from the original on 22 December 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2021 – via Newspapers.com

.

. - ↑ "'It's not me kicking it' – Jonny Wilkinson recalls World Cup-winning moment". BBC Sport. 28 November 2019. Archived from the original on 22 December 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- 1 2 "Rugby World Cup 2003: What They Said". The Advertiser. 24 November 2003. p. 042. Archived from the original on 24 December 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2021 – via Gale OneFile: News.

- ↑ "Greenwood memorial to son Freddie". ESPNscrum. 26 November 2003. Archived from the original on 22 December 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ↑ "England jubilant". Scrum.com. 22 November 2003. Archived from the original on 3 March 2004. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ↑ Tucker, Jim (23 November 2003). "Elton keeps his cool – Flatley's gutsy strikes in vain". The Courier-Mail. p. 011. Archived from the original on 24 December 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2021 – via Gale OneFile: News.

- ↑ Weidler, Danny (30 November 2003). "Mat admits touch-bid torment". The Sun-Herald. p. 109. Archived from the original on 24 December 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2021 – via Gale OneFile: News.

- 1 2 Godwin, Hugh (30 November 2003). "Woodman: the referee nearly blew it for us". The Independent on Sunday. Archived from the original on 23 December 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- 1 2 Hollely, Andrew (28 November 2003). "Woodward takes Watson to task over RWC final". Independent Online. South African Press Association. Archived from the original on 23 December 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ↑ "England rugby heroes arrive home". BBC Sport. 25 November 2003. Archived from the original on 19 April 2009. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ↑ Tait 2013

- ↑ Wilkes, Neil (24 November 2003). "Massive ratings for England's World Cup win". Digital Spy. Archived from the original on 24 December 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- 1 2 "RWC final tops TV viewing figures". ESPNscrum. 16 December 2003. Archived from the original on 22 February 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ↑ Warneke, Ross (27 November 2003). "Rugby rewrites records". The Age. p. 16. Archived from the original on 24 December 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2021 – via Gale Academic OneFile.

- ↑ Peatey 2011, pp. 179, 203–204

Bibliography

- Team England Rugby (2003). World Cup 2003: The official Account of England's World Cup triumph. London, England: Orion Media. ISBN 0-7528-6048-8 – via Open Library.

- Jones, Stephen (2004). On My Knees: The Pains and Passions of England's Attempt on the 2003 Rugby World Cup. Edinburgh, Scotland: Mainstream Publishing. ISBN 1-84018-708-5 – via Open Library.

- Welch, Ian (2007). "England Beat Australia in the World Cup Final 2003". Greatest Moments of Rugby. Swindon, Wiltshire: Green Umbrella Publishing. ISBN 978-1-906229-40-5 – via Open Library.

- Peatey, Lance (2011) [2007]. A Complete History of the Rugby World Cup: In Pursuit of Bill (Second ed.). Croydon, South London: New Holland Publishers. ISBN 978-1-78009-219-5 – via Open Library.

- Tait, Paul (2013). Rugby World Cups – 2003 and 2015: What's happened in between and can England repeat the success?. Luton, Bedfordshire: Andrews UK. ISBN 978-1-78333-353-0.

- Ceberano, Kate; Gilling, Tom (2014). I'm Talking: My Life, My Words, My Music (eBook ed.). Didcot, Oxfordshire: Hachette UK. ISBN 978-0-7336-3038-5.

- Clark, Joe (2015). Rugby World Cup: A History in 50 Greatest Games. Durrington, West Sussex: Pitch Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78531-053-9 – via Open Library.

- Smith, Martin, ed. (2015). The Telegraph Book of the Rugby World Cup. Islington, London: Aurum Press. ISBN 978-1-78131-493-7 – via Open Library.

- Hawkes, Chris (2015) [2012]. World Rugby Records (Fourth ed.). London, England: Carlton Books. ISBN 978-1-78097-719-5 – via Open Library.

External links

- Australia v England – Final – rwc2003.irb.com

- Australia 17–20 England