| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Routes of administration | Oral, intranasal, injection, |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Elimination half-life | 6-12 hours |

| Excretion | Urine |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C10H15N |

| Molar mass | 149.237 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

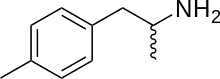

4-Methylamphetamine (4-MA; PAL-313; Aptrol; p-TAP) is a stimulant and anorectic drug of the phenethylamine and amphetamine chemical classes.

In vitro, it acts as a potent and balanced serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine releasing agent with Ki affinity values of 53.4nM, 22.2nM, and 44.1nM at the serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine transporters, respectively.[1] However, more recent in vivo studies that involved performing microdialysis on rats showed a different trend. These studies showed that 4-methylamphetamine is much more potent at elevating serotonin (~18 x baseline) relative to dopamine (~5 x baseline). The authors speculated that this is because 5-HT release dampens DA release through some mechanism. For example, it was suggested that a possible cause for this could be activation of 5HT2C receptors since this is known to inhibit DA release. In addition there are alternative explanations such as 5-HT release then going on to encourage GABA release, which has an inhibitory effect on DA neurons.[2]

4-MA was investigated as an appetite suppressant in 1952 and was even given a trade name, Aptrol, but development was apparently never completed.[3] More recently it has been reported as a novel designer drug.

In animal studies, 4-MA was shown to have the lowest rate of self-administration out of a range of similar drugs tested (the others being 3-methylamphetamine, 4-fluoroamphetamine, and 3-fluoroamphetamine), likely as a result of having the highest potency for releasing serotonin relative to dopamine.[4][5]

More than a dozen deaths were reported throughout Europe in 2012-2013 after consumption of amphetamine ('speed') contaminated with 4-methylamphetamine.[6]

See also

References

- ↑ Wee S, Anderson KG, Baumann MH, Rothman RB, Blough BE, Woolverton WL (May 2005). "Relationship between the serotonergic activity and reinforcing effects of a series of amphetamine analogs". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 313 (2): 848–54. doi:10.1124/jpet.104.080101. PMID 15677348. S2CID 12135483.

- ↑ Di Giovanni G, Esposito E, Di Matteo V (June 2010). "Role of serotonin in central dopamine dysfunction" (PDF). CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics. 16 (3): 179–94. doi:10.1111/j.1755-5949.2010.00135.x. PMC 6493878. PMID 20557570.

- ↑ Gelvin EP, McGAVACK TH (January 1952). "2-Amino-1-(p-methylphenyl)-propane (aptrol) as an anorexigenic agent in weight reduction". New York State Journal of Medicine. 52 (2): 223–6. PMID 14890975.

- ↑ Wee S, Anderson KG, Baumann MH, Rothman RB, Blough BE, Woolverton WL (May 2005). "Relationship between the serotonergic activity and reinforcing effects of a series of amphetamine analogs". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 313 (2): 848–54. doi:10.1124/jpet.104.080101. PMID 15677348. S2CID 12135483.

- ↑ Baumann MH, Clark RD, Woolverton WL, Wee S, Blough BE, Rothman RB (April 2011). "In vivo effects of amphetamine analogs reveal evidence for serotonergic inhibition of mesolimbic dopamine transmission in the rat". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 337 (1): 218–25. doi:10.1124/jpet.110.176271. PMC 3063744. PMID 21228061.

- ↑ Blanckaert P, van Amsterdam J, Brunt T, van den Berg J, Van Durme F, Maudens K, van Bussel J (September 2013). "4-Methyl-amphetamine: a health threat for recreational amphetamine users". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 27 (9): 817–22. doi:10.1177/0269881113487950. PMID 23784740. S2CID 35436194.