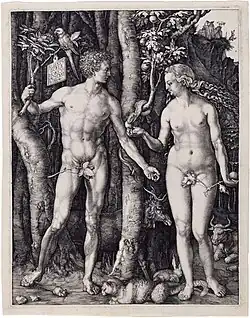

Adam and Eve is the title of two famous works in different media by Albrecht Dürer, a German artist of the Northern Renaissance: an engraving made in 1504, and a pair of oil-on-panel paintings completed in 1507.

The engraving of 1504 depicts Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, with several symbolic animals around them.[1] This famous engraving transformed how Adam and Eve were popularly depicted in art.[2]

The 1507 painting in the Museo del Prado offered Dürer another opportunity to depict the ideal human figure in a different medium.[3] Painted in Nuremberg soon after his return from Venice, the panels were influenced by Italian art.[3] Dürer's observations on his second trip to Italy provided him with new approaches to portraying the human form. Here, he depicts the figures at human scale—the first full-scale nude subjects in German painting.[3]

Engraving of Adam and Eve (1504)

Background and historical context

Dürer was perpetually chasing perfection in his work.[4] In this pursuit, he traveled to Italy to study the Italian Renaissance masters and incorporate their techniques into his art.[3] His first trip took place in 1494 where he studied great artists such as Giovanni Bellini, Andrea Mantegna, Leon Alberti, and more.[4]One work of art that particularly captured his attention was The Birth of Venus (c. 1484–1486) by Sandro Botticelli.[3][4] In addition, he was greatly influenced by two ancient classical marble sculptures (both copied after Greek Hellenistic sculptures, now lost) that illustrate the concept of ideal male and female beauty: the Apollo Belvedere and the Medici Venus, though Dürer likely discovered these works through second-hand sources, including the print of Apollo and Diana (c. 1503) made by Jacopo de' Barbari.[1][4][5] This image featured the intricately modeled figure of Apollo in classical Italian Renaissance contrapposto, later inspiring Dürer's interpretation of Adam.[3] Similarly, in Botticelli's The Birth of Venus, the figure of Venus acted as a model for Dürer's later renditions of Eve. [4] Raptured by newfound inspiration, Dürer returned to Nuremberg and in 1504 created the famous engraving Adam and Eve (burin on copperplate, 25.1 x 19.8 cm).[6]

Imagery, style, and symbolism

The engraving captures an idealistic Adam and Eve before the Fall of Man.[1][7] Both Adam and Eve are depicted as the ideal body shape of both man and woman respectively.[3] This engraving was one of the first depictions of Adam and Eve that focused on human physical beauty rather than the depiction of sin, causing many artists to later draw inspiration from this perspective shift.[5] As the first man and woman sculpted by God, Adam and Eve serve as the perfect characters to embody the ideal human figure.[5]Both figures are nude and posed in Italian contrapposto. Dürer, wielding an astonishing technical sophistication, uses the engraved line work to play with light and dark shadows (known as chiaroscuro), illuminating and modeling the musculature of each body.[5] Keeping with ancient tradition, Adam is depicted more lean and muscular while Eve's body is more supple and rounded.[4]

Beyond the figures of Adam and Eve, the background is equally significant. Adam and Eve are shown in the Garden of Eden.[3] Since this image is a depiction of the story from before the Fall, everything remains in perfect harmony. For example, place directly between the pair of figures stands a mountain ash, the Tree of Knowledge, but is represented here as a hybrid tree since the fruit of the tree is apple.[1][2][4][8] In addition, Eve holds a broken branch in front of her genitals that is adorned with fig leaves.[1][2][8] Dürer's inclusion of the fig leaves is a direct reference to the shame that Adam and Eve would experience after the Fall, as described in Genesis 3:7: "And the eyes of both were opened, and they knew that they were naked; and they sewed fig leaves together and made themselves aprons."[4]

Eve is grasping the Forbidden Fruit from the tree in her left (sinister in Latin) hand, symbolizing evil.[2][4] The parrot can symbolize different ideas, including: wisdom, the Word of God, Christ, eternal life, and paradise, but could also refer to the New World.[1][4][9] At this time, the colonization of the New World was in full swing and certain objects from the Americas came to symbolize paradise, as Europeans had come to believe paradise would be found in the Americas.[9] Thus, certain objects that originated from the New World became common symbols of paradise in art, a possible meaning for the parrot represented here.[9] Moreover, it is known through his diary writings that Dürer saw and even collected exotic items from the East (the Orient), as well as the Americas while on trips to both Venice and Brussels.[10] Some of these marvelous objects included a large fishbone, porcelain dishes from China, while other items like cloths (some made out of silk), feathers, an ivory salt-cellar came from "Calicut," which in the Renaissance was a catch-all term that could reference India, Africa or the Americas, indicating a geographical misunderstanding of the wider world.[10]

The little plaque (cartellino in Italian), written in Latin, reads "Albert Dürer noricvs faciebat 1504," which translates to "Albrecht Dürer of Nuremberg was making [this in] 1504."[1] Despite Dürer's fascination with Italian art, this inscription demonstrates his pride regarding his Northern heritage, clearly identifying his hometown as the German city of Nuremberg (Noricus in Latin).[1] Moreover, Dürer is subtly flaunting the immortality of his work since the plaque hangs from a branch on the Tree of Life.[5]

Below Adam and Eve lie four animals to represent the four humors or temperaments.[5] The cat symbolizes the choleric humor, the rabbit symbolizes the sanguine temperament, the ox represents the phlegmatic humor, and the elk is the melancholic temperament .[1] The common belief of the time was that an imbalance of bodily fluids caused these undesirable humors.[4] However, in Eden, everything is in perfect harmony, therefore, the bodily fluids must be as well. [1][5] Visually, this is represented by the peaceful cohabitant nature of the animals: the cat is not pouncing on the mouse, the ox is sitting calmly.[4] This representation of balanced harmony, however, would be forever destroyed once the Fall occurred. [5] Finally, the relationship of the mouse and feline at the feet of the figures parallels that of Adam and Eve.[11]

Provenance

During his lifetime, the Adam and Eve's print was printed many time, resulting in multiple prints of this engraving that survive today in different collections.[1][4] [5]In addition, copies of his print were made during Durer's lifetime in Florence, Italy, now at the Uffizi, and one made in Mainz, Germany during the time of Napoleon.[2][3] Currently, copies survive at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, The Art Institute of Chicago, The British Museum in London, The Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Yale University Art Gallery, among many others.

Provenance of engraving located at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Ernst Theodore Rodenacker(1837-1894), a German art collector.[8]

- Junius Spencer Morgan (1813-1890), an American banker and seller of this engraving.[8]

Provenance of engraving located at The Art Institute of Chicago

- Pierre Mariette (1634-1716), grandfather of Pierre Jean Mariette held the engraving in Paris.[12]

- Sir Francis Seymour Haden (1818-1910), a founder of printmaking, held this in London along with other works from artists such as Rembrandt.[12]

- John Pierpont Morgan (1837-1913), American banker and son of Junius Spencer Morgan, who owned of other engraving.[12]

- Emil Hirsch sold this piece to The Art Institute of Chicago in 1944.[12]

Oil paintings of Adam and Eve (1507)

_2.jpg.webp)

Background and historical context

After the creation of the engraving of 1504, Dürer revisited the subject of Adam and Eve after a second visit to Italy, when he spent most of his time in Venice to further study Italian Renaissance paintings.[3][13] During his two years in Venice, from 1505 until 1507, Dürer analyzed various techniques and famous works of art, developing his use of classical Italian contrapposto.[6] Returning to Nuremberg with his newly acquired skill and knowledge, Dürer painted in 1507 what is considered to be the first life-sized nude painting in German art, Adam and Eve (oil on wood, 209 x 81 cm per panel).[3]

Imagery, style, and symbolism

Dürer believed the way to paint the ideal human form was through a precise mathematical system of proportions.[8] In his oil painting of Adam and Eve, Dürer altered the proportions of the head to the body of Eve's figure from the 1:7.4 ratio of the engraving to 1:8.2.[3] This alteration visually elongated Eve's body, providing her with a slender, weightless quality.[13] This weightlessness was typical of Gothic figure depictions, illuminating a stylistic shift from the classical contrapposto of the engraving figures.[3][4] This can further be seen in the positioning of the limbs: Eve's legs are crossed, one directly behind the other rather than the more grounded-appearing side by side stance as seen in the engraving.[3] This new rendition of Eve acted as a template for many later female nude paintings.[6] Adam's figure, however, remains in contrapposto, still reminiscent of the classical depictions of Apollo.[14] Both figures are presented more androgynously than in the 1504 engraving, likely the result of a return to a more Gothic style.[4]

Lighting is also strategically used to emphasize the figures. Adam is awash with warm light, contrasting Eve who is bathed in cool toned, almost slivery, light.[3] The color palette as a whole is strategic, using subtle light and dark shadows to minimize contrast and allow the painting a subtly.[3] This choice is in opposition to the 1504 engraving where, due to the nature of the material, everything is sharp with high contrast.[8] In the oil painting, Adam holds a tree branch, meant to symbolize the mountain ash that symbolizes the Tree of Life just as the branch in the engraving does.[8][14] Eve rests her hand above a branch where a cartellino hangs with Latin writing that reads,"Albertus durer alemanus faciebat post virginis partum 1507," ("Albrecht Dürer, upper German, made this 1507 years after the Virgin's offspring.")[3]

The oil painting consists of two separate rectangular panels: one of Adam and one of Eve. The division of panels indicates that the two figures are independent of each other, unlike the engraving, in which they are dependent.[3] While the engraving of 1504 communicates the story of the Fall of Man, the oil painting is primarily focused on the individual figures of Adam and Eve, emphasized by the lack of intricate background and symbolism.[3][8] The actual reason behind Dürer's choice to paint Adam and Eve separately remains unknown, however, it was one of the first works of art to create a division of the subjects, an artistic choice that many later artists copied.[3]

Restoration

.jpg.webp)

As mentioned before, the oil painting of 1507 was done on wooden panels. Wood and paint both have complex aging processes, leading to difficulty in both conservation and restoration.[15] Over time, multiple attempts at restoration led to the addition of layers of new paint and oxidized varnish, which in turn distorted the original image.[15] Moreover, the back of the wooden panels had been reinforced in an attempt to prevent warping of wood.[15] Unfortunately, these reinforcements ultimately had the opposite effect, distorting the panels further.[15] The Met and the Museo del Prado collaborated to restore the painting to its original condition in 2020.[15] Removing the back support panels, smoothing the wood, removing oxidized varnish, and finally taking off additional attempts at restorative painting touch-ups, the painting was returned to what is believed to be its original state.[15] Due to the oxidized varnish, the image previously had an overall green hue. Now, that green hue is gone and the colors are as Dürer painted them.[15]

Provenance

There is no extant archival documents that shed light on the original patron of the paintings of Adam and Eve.[16] Scholars have suggested that they may have been commissioned to adorn the Town Hall in the city of Nuremberg, Dürer's hometown, as they were installed there at the end of the sixteenth century.[16] In turn, the Nuremberg City Council gave them as a gift to Emperor Rudolph II who displayed them in his new gallery room at Prague Castle.[16] During the Thirty Years' War, armies stormed the city, an event that came to be known as the Battle of Prague (1648).[16] The Swedes plundered the castle and moved the panels to Stockholm and then entered the collection of Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden.[16] His daughter, Christina of Sweden, gave the work to Philip IV of Spain in 1654, after her abdication.[16] The works moved next to The Royal Palace of Madrid, but were considered "nudes" so were relocated and displayed in a separate room known as the "Vaults of Titian."[16] This vault survived the fire in 1734 that destroyed much of the palace and its art.[16] The paintings were then transported to the Buen Retiro palace.[16] In 1762, if not for the persuasion of Anton Raphael Mengs, King Charles III of Spain's court painter at the time, the paintings would have been destroyed in because they were perceived as being "indecent" because of the nudity.[16] Mengs convinced the king that they panels were important pieces to study.[16] About ten years later, the paintings were moved to the Academia de San Fernando for storage.[16] The remained stored away for several decades and were able to be freely viewed n the Sala de Juntas between 1809 and 1818, which was during the rule of Jose Bonaparte.[16] In 1827, the two panels were moved to their current location, the Museo del Prado in Madrid, where they remained out of public view because of their nudity until 1838, when they finally were displayed to the public.[16]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Harbison, Craig (1995). The Mirror of the Artist: Northern Renaissance Art in Its Historical Context. Perspectives. New York, NY: Harry N. Abrams. pp. 166–167. ISBN 0-8109-2728-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Porras, Stephanie (2018). Art of the Northern Renaissance: Courts, Commerce and Devotion. London: Laurence King Publishing. pp. 133–134. ISBN 978-1-78627-165-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Strieder, Peter (1982). Albrecht Dürer, Paintings, Prints, Drawings. Translated by Gordon, Nancy M.; Strauss, Walter L. New York, NY: Abaris Books. pp. 168–173. ISBN 978-0898350425.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Snyder, James (2005). Northern Renaissance Art: Painting, Sculpture, the Graphic Arts, from 1350 to 1575. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. pp. 303–306, 321–322. ISBN 0-13-189564-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Smith, Jeffery Chipps (2004). The Northern Renaissance. London; New York, NY: Phaidon. pp. 263–266. ISBN 978-0-7148-3867-0.

- 1 2 3 Rossiter, Henry (1971). "Dürer the Incomparable". Boston Museum Bulletin. 95 (3): 96–130 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Laz, Lauren; Masson, Olivier; Ritter, Michaela (September 2014). "Dürer's "Adam and Eve" and a Possible 'Schweidlerization'". Print Quarterly. 31 (3): 259–269. ISSN 0265-8305 – via JSTOR.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Albrecht Dürer | Adam and Eve". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2023-04-17.

- 1 2 3 Jaffe, Irma B. (1993). "The Tell-Tale Tail of a Parrot: Dürer's "Adam and Eve"". The Print Collector's Newsletter. 24 (2): 52–53. ISSN 0032-8537 – via JSTOR.

- 1 2 Newall, Diana, ed. (2017). Art and its Global Histories: A Reader. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. 57–59. ISBN 9781526119926. OCLC 1007645503.

- ↑ Wallace, Robert (1968). The World of Rembrandt: 1606-1669. New York, NY: Time-Life Books. p. 71.

- 1 2 3 4 "Adam and Eve". The Art Institute of Chicago. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- 1 2 Strieder, Peter (2003). "Dürer family". Grove Art Online – via Oxford Art Online.

- 1 2 Moser, Peter (2005). Albrecht Dürer: His Life, His World, and His Art. Bamberg: Babenberg Verlag Gmbh. ISBN 3-933469-16-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Abraham, Melissa (2010-11-29). "Dürer's Conserved "Adam" and "Eve" Unveiled at the Prado". Getty Iris. Retrieved 2023-04-11.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 "Special Display: Adam and Eve, by Dürer, following their restoration - Exhibition - Museo Nacional del Prado". www.museodelprado.es. Retrieved 2023-04-12.

External links

- The 1504 print at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- The Adam panel at the Museo del Prado

- The Eve panel at the Museo del Prado