Agostino Depretis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Prime Minister of Italy | |

| In office 29 May 1881 – 29 July 1887 | |

| Monarch | Umberto I |

| Preceded by | Benedetto Cairoli |

| Succeeded by | Francesco Crispi |

| In office 19 December 1878 – 14 July 1879 | |

| Monarch | Umberto I |

| Preceded by | Benedetto Cairoli |

| Succeeded by | Benedetto Cairoli |

| In office 25 March 1876 – 24 March 1878 | |

| Monarchs | Victor Emmanuel II Umberto I |

| Preceded by | Marco Minghetti |

| Succeeded by | Benedetto Cairoli |

| Minister of the Interior | |

| In office 25 November 1879 – 29 July 1887 | |

| Prime Minister | Benedetto Cairoli Himself |

| Preceded by | Tommaso Villa |

| Succeeded by | Francesco Crispi |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | |

| In office 4 April 1886 – 29 July 1886 | |

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Carlo Felice Nicolis |

| Succeeded by | Francesco Crispi |

| In office 29 June 1885 – 6 October 1885 | |

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Pasquale Stanislao Mancini |

| Succeeded by | Carlo Felice Nicolis |

| In office 19 December 1878 – 14 July 1879 | |

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Benedetto Cairoli |

| Succeeded by | Benedetto Cairoli |

| In office 26 December 1877 – 24 March 1878 | |

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Luigi Amedeo Melegari |

| Succeeded by | Luigi Corti |

| Minister of Finance | |

| In office 25 March 1876 – 26 December 1877 | |

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Girolamo Cantelli |

| Succeeded by | Agostino Magliani |

| In office 17 February 1867 – 10 April 1867 | |

| Prime Minister | Bettino Ricasoli |

| Preceded by | Antonio Scialoja |

| Succeeded by | Francesco Ferrara |

| Minister of the Navy | |

| In office 20 June 1866 – 17 February 1867 | |

| Prime Minister | Bettino Ricasoli |

| Preceded by | Diego Angioletti |

| Succeeded by | Giuseppe Biancheri |

| Minister of Public Works | |

| In office 3 March 1862 – 8 December 1862 | |

| Prime Minister | Urbano Rattazzi |

| Preceded by | Ubaldino Peruzzi |

| Succeeded by | Luigi Federico Menabrea |

| Member of the Chamber of Deputies | |

| In office 18 February 1861 – 29 July 1887 | |

| Constituency | Stradella |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 31 January 1813 Stradella, Lombardy, Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy |

| Died | 29 July 1887 (aged 74) Stradella, Lombardy, Kingdom of Italy |

| Political party | Historical Left |

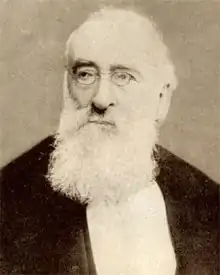

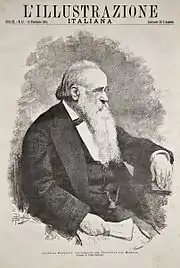

Agostino Depretis (31 January 1813 – 29 July 1887) was an Italian statesman and politician. He served as Prime Minister of Italy for several stretches between 1876 and 1887, and was leader of the Historical Left parliamentary group for more than a decade. He is the fourth-longest serving Prime Minister in Italian history, after Benito Mussolini, Giovanni Giolitti and Silvio Berlusconi, and at the time of his death he was the longest-served. Depretis is widely considered one of the most powerful and important politicians in Italian history.[1]

He was a master in the political art of Trasformismo, the method of making a flexible, centrist coalition of government which isolated the extremes of the left and the right in Italian politics after the unification.[2]

Early life and Italian Unification

Depretis was born at Bressana Bottarone, near Stradella, which at the time was a province of the French Empire of Napoleon and now is in the province of Pavia, Lombardy.[3] After Napoleon's defeat and restoration of the Kingdom of Sardinia, Depretis graduated in law and started working as lawyer.

From early manhood he was a disciple of Giuseppe Mazzini and affiliated with the La Giovine Italia. He took an active part in the Mazzinian conspiracies and was nearly captured by the Austrians while smuggling arms into Milan. Elected deputy in 1848, he joined the Left and founded the newspaper Il Diritto, but he held no political offices.[4]

In the same period he strongly opposed the policies of the Piedmontese Prime Minister Camillo Benso di Cavour and voted against the main reforms that he presented, including the bill regarding the Piedmontese participation to the Crimean War. Despite their struggles, after the annexation of Lombardy by the Kingdom of Sardinia in 1859, Cavour appointed Depretis governor of Brescia.[5]

In 1860, Giuseppe Garibaldi sailed with his Expedition of the Thousand toward Sicily. The Expedition was formed by corps of volunteers led by Garibaldi in order to conquer the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, ruled by the Bourbons. The project was an ambitious and risky venture aiming to conquer, with a thousand men, a kingdom with a larger regular army and a more powerful navy. The expedition was a success and concluded with a plebiscite that brought Naples and Sicily into the Kingdom of Sardinia, the last territorial conquest before the creation of the Kingdom of Italy on 17 March 1861.[6]

The sea venture was the only desired action that was jointly decided by the "four fathers of the nation" Giuseppe Mazzini, Giuseppe Garibaldi, Victor Emmanuel II, and Camillo Cavour, pursuing divergent goals.[7] The various groups participated in the expedition for a variety of reasons: for Garibaldi, it was to achieve a united Italy; to the Sicilian bourgeoisie, an independent Sicily as part of the kingdom of Italy, and for the mass farmers, land distribution and the end of oppression.[7]

In 1860 Depretis went to Sicily on a mission to reconcile the policy of Cavour, who desired the immediate incorporation of the island in the Kingdom of Italy, with that of Garibaldi, who wished to postpone the Sicilian plebiscite until after the liberation of Naples and Rome. Depretis replaced Garibaldi's close councilor Francesco Crispi as pro-dictator (prodittatore) of Sicily, during the dictatorial government; however he failed in his attempt to win round Garibaldi and his comrades to the idea of immediately incorporating Sicily into the new Italian kingdom, and resigned in September 1860.[8]

In government

Minister of Public Works

After Cavour's death king Victor Emmanuel II gave the task to form a new government firstly to Bettino Ricasoli and then to Urbano Rattazzi; Rattazzi was the leader of the Left and created a cabinet composed by both political groups. On 3 March 1862, Depretis was appointed Minister of Public Works, and served as intermediary in arranging with Garibaldi.[9]

However, in August 1862 the Royal Italian Army defeated Garibaldi's army of volunteers, who were marching from Sicily towards Rome, with the intent of annexing it into the Kingdom of Italy. In the battle, which took place a few kilometers from Gambarie, Garibaldi was wounded and taken as prisoner. Rattazzi's policy of repression towards Garibaldi at Aspromonte, caused lot of public protests and the Prime Minister was forced to resign in September 1862.[8][10]

Moreover, Francesco Crispi accused Depretis of having mounted the Mazzinian riots in Sarnico in May 1862 to discredit Garibaldi. After the fall of the Rattazzi government, therefore, it was easy to predict the end of Depretis's political career, when Crispi was elected leader of the Left.[11] Depretis remained on the sidelines during the 8th legislature (1863–65), but he regularly participated in the parliamentary works, intervening regarding the laws for administrative unification and declaring himself hostile to regionalism. He was particularly active during the electoral campaign of 1865 and at the beginning of the 9th legislature he was elected Vice President of the Chamber of Deputies.[12]

Minister of Navy

In 1866, in anticipation of the war with the Austrian Empire, after the signing of the Italo-Prussian alliance, Ricasoli was appointed Prime Minister by the king to replace General Alfonso Ferrero La Marmora, who would lead the Italian troops during the war. The king wanted to established a government of "national conciliation" that included members both form the Right and the Left.

On 20 June, Depretis was appointed Minister of the Navy,[8] on the same day the Third Italian War of Independence began.[13] After the Italian defeat in the Battle of Custoza, Depretis insisted with admiral Carlo Persano on the attack against the island of Lissa, as a revenge for Custoza. But he also refused to give to admiral Persano detailed orders about the expedition in the Adriatic Sea against the fleet led by Wilhelm von Tegetthoff. However the Italian Royal Navy was soundly defeated. To quell the public outcry after the two defeats, Depretis called for process Persano, who was judged by the Italian Senate, condemned for incompetence in 1867 and cashiered from duty.[14] However the war ended in an Austrian defeat, with Austria conceding the region of Venetia to Italy. Italy's acquisition of this wealthy and populous territory represented a major step in the process of Italian unification.[15]

On 17 February 1867, Depretis resigned as Minister of the Navy. His tenure as minister was quite controversial, his apologists contend, however, that, as an inexperienced civilian, he could not have made sudden changes in naval arrangements without disorganizing the fleet, and that in view of the impending hostilities he was obliged to accept the dispositions of his predecessors.[8]

Leader of the Left

On 17 February 1867 Depretis was appointed Minister of Finance in the second cabinet of Ricasoli; however after few months, on 10 April, Ricasoli resigned and Depretis returned to be a simple deputy.

Upon the death of Rattazzi in 1873, Depretis became leader of the Left. On 25 June 1873, the conservative government of Giovanni Lanza fell, beaten by a vote that saw the Depretis's moderate Left united with a large part of the Right, no longer in support of the Minister of Finance Quintino Sella; in fact Sella abandoned the proposal of a further fiscal tightening in order to achieve a balanced budget.[16] Victor Emmanuel II then asked the conservative Marco Minghetti to form a new government, inviting him to include also members from the Left. Minghetti accepted the suggestion but his efforts to agree with Depretis were vain.

Minghetti and Sella were involved into an ambitious program of budget which needed a strong majority, for which they tried to oblige the Independents to choose their side, beginning to build a two-party system as in the United Kingdom.[17] However, in the Italian non-partisan political system, hugely affected by localism and corruption, their bet was equivalent to an all-in that afterwards they lost.[18]

The 1874 election did not give to Minghetti the advantage he was hoping, especially for the high support to Depretis's opposition in Southern Italy.[19] Minghetti's government survived, but the bipolarisation of the Parliament he had imposed, strengthened the Left so that it could take the leadership of the country. Two years later, MPs from Tuscany became dissatisfied with the government after it refused to intervene in the financial problems of Florence. The government was defeated on a vote on nationalising railways on 18 March 1876 and Minghetti was forced to resign.[20] As a result, Depretis became Prime Minister, with 414 of the 508 MPs supporting the government.[21] The fall of the Minghetti's cabinet was called, by political commentators, the "parliamentary revolution".[22]

Prime Minister of Italy

First term

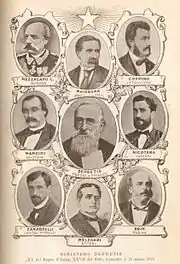

On 25 March 1876, Depretis sworn in as Prime Minister; his cabinet was the first one to be composed only by members of the Left. Prominent ministers were Giovanni Nicotera, Pasquale Stanislao Mancini, Michele Coppino, Giuseppe Zanardelli and Benedetto Brin.

To strengthen his position, Depretis called for new election in November.[20] For the first time, the left-wing won an election, gaining almost 70% of votes and taking 414 of the 508 seats, of which 12 were extreme left-wingers.[20] As opposed to the previous right-wing governments, whose members were largely aristocrats representing rentiers from the north of the country, and held moderate political views including loyalty to the crown and low government spending,[23] the left-wing government represented the bourgeoisie of the south of the country and supported low taxation, secularism, a strong foreign policy and public jobs.[20]

The main reform proposed by the government was the school one that took its name from Minister Coppino and was presented on 15 July 1877. The law introduced compulsory, secular and free primary education for children aged six to nine. On the other hand, while maintaining the electoral promises, Depretis raised the minimum exemption for the mobile wealth tax from 250 to 800 lire, granting greater deductions for industrial income. Important, although not very effective, was the decree of 25 August 1876 which regulated the office of the Prime Minister with the will to contain the monarchical power and above all the conflict of ministers.

The foreign policy of his first government was prudent, similar to that of the cabinets which had preceded it. His policies created criticisms from the progressives who were pushing for an approach to German Empire to fight France. This francophobic attitude increased in May 1877 when the government of Albert de Broglie, favorable to clericals positions, sworn in Paris. The government however had to face the violent attacks against the Minister of the Interior Nicotera, who was considered guilty, according to a part of the majority, of abuses and illegality; unable to cope with the crisis, Depretis decided to resign in December 1877.

The king, gave again to Depretis the task of forming a new cabinet; it was the last political act of the king who would die after few months. Depretis failed in stopping the contrasts within the Left. He was criticized for having abolished the Ministry of Agriculture, Industry and Commerce and having established the Ministry of Treasury in order to achieve greater control over state budget. On 11 March 1878, Depretis resigned from his office, when his candidate lost the election to become President of the Chamber of Deputies; the following cabinet was led by another prominent leftist member Benedetto Cairoli.

Second term

In November 1879, Depretis joined the Cairoli cabinet as Minister of the Interior. In the same period, a general irritation was caused by Cairoli and Count Corti's policy of clean hands at the Berlin Congress, where Italy obtained nothing, while Austria-Hungary secured a European mandate to occupy Bosnia and Herzegovina. A few months later the attempt of Giovanni Passannante to assassinate King Humbert I at Naples on 12 December 1878, caused Cairoli's downfall.[8]

Depretis was appointed Prime Minister by the king; his cabinet was formed by members of the Left and of the Right. On 24 June 1879 the Italian Senate approved, with significant amendments, the bill on the abolition of the tax on the mill. However, on 3 July, the Chamber rejected the law and voted down the government; third cabinet of Depretis therefore had to resign after only six months of troubled political life and the next government was again led by Cairoli, on 14 July.

Third term

Following the French occupation of Tunis on 11 May 1881, in view of popular indignation Cairoli resigned in order to avoid making inopportune declarations to the Chamber. The king, after the failed attempt by Quintino Sella to establish a new cabinet, appointed Depretis once again Prime Minister.

On 20 May 1882, Depretis signed the Triple Alliance, a secret military agreement between Italy, Germany and Austria-Hungary to oppose the power of France and Russia. Italy sought support against France shortly after it lost North African ambitions to the French. Each member promised mutual support in the event of an attack by any other great power. The treaty provided that Germany and Austria-Hungary were to assist Italy if it was attacked by France without provocation. In turn, Italy would assist Germany if attacked by France. In the event of a war between Austria-Hungary and Russia, Italy promised to remain neutral.

In domestic policy, 1882 saw the approval of the electoral reform of which Depretis had also become the main spokesman and on 22 January the parliament approved what the Prime Minister had called "the only possible universal suffrage". All men of at least 21 years of age who had attended at least the first two years of elementary school or who contributed an annual tax of no less than 19.80 lire were entitled to vote. the voting age was lowered from 25 to 21 and the tax requirement lowered from ₤40 to ₤19.80, whilst men with three years of primary education were exempted from it.[24] This resulted in the number of eligible voters increasing from 621,896 at the 1880 elections to 2,017,829.[25] The electoral system was changed from one based on single-member constituencies to one based on small multi-member constituencies with between two and five seats.[24] Voters had as many votes as there were candidates, except in constituencies with five seats, in which they were limited to four votes.[26] To be elected in the first round a candidate needed an absolute majority of the votes cast and to receive a number of votes equivalent to at least one-eighth of the number registered voters. If a second round was required, the number of candidates going through was double the number of seats available.[26]

In the 1882 general election the Left emerged as the largest in Parliament, winning 289 of the 508 seats; the Right arrived second with 147 seats.[27] Depretis was confirmed Prime Minister by the king.

During his long tenure Depretis recomposed his cabinet four times, first throwing out Giuseppe Zanardelli and Alfredo Baccarini in order to please the Right, and subsequently bestowing portfolios upon Cesare Ricotti-Magnani, Robilant and other Conservatives, so as to complete the political process known as Trasformismo.[8]

Depretis also completed the railway system and initiated colonial policy by the occupation of Massawa; but, at the same time, he increased indirect taxation, corrupted the parliamentary parties, and, by extravagance in public works, impaired the stability of Italian finance.[8] He argued that a wider suffrage would give citizens a moral dignity and sense of responsibility.[28]

Despite an insistent gout, Depretis remained Prime Minister until his death. More and more often he gathered the government in the living room of his house, at Via Nazionale in Rome. Transferred to Stradella due to the aggravation of the disease, he died there on 29 July 1887, at 74 years old. After the funeral he was buried in the cemetery of his home town. He was replaced at the head of the Left and at the head of the government by Francesco Crispi.

Political ideology and legacy

Depretis was the founder and the main proponent of Trasformismo ("Transformism"), a method of making a flexible centrist coalition of government which isolated the extremes of the left and the right. The process was initiated in 1883, when he moved to the right and reshuffled his government to include Marco Minghetti's conservatives. This was a move Depretis had been considering for a while before 1883. The aim was to ensure a stable government that would avoid weakening the institutions by extreme shifts to the left or right. Depretis felt that a secure government could ensure calm in Italy.

At this time middle class politicians were more concerned with making deals with each other and less about political philosophies and principles. Large coalitions were formed, with members being bribed to join them. The liberals, the main political group, was tied together by informal "gentleman's agreements", but these were always in matters of enriching themselves. Indeed, actual governing did not seem to be happening at all, but since only 2 million men had franchises, most of these wealthy landowners did not have to concern themselves with such things as improving the lives of the people they were supposedly representing democratically.

However trasformismo fed into the debates that the Italian parliamentary system was weak and actually failing; it ultimately became associated with corruption. It was perceived as the sacrifice of principles and policies for short term gain. The system of trasformismo was little loved and seemed to be creating a huge gap between 'Legal' (parliamentary and political) Italy, and 'Real' Italy where the politicians became increasingly isolated. This system brought almost no advantages, illiteracy remained the same in 1912 as before the unification era, and backward economic policies, combined with poor sanitary conditions, continued to prevent the country's rural areas from improving.

References

- ↑ La dittatura parlamentare di Giolitti

- ↑ Killinger, The history of Italy, p. 127–28

- ↑ Agostino Depretis – Dizionario Biografico

- ↑ Depretis Agostino, pages 60-61

- ↑ Il presidente del Consiglio, in Illustrazione Italiana, Anno XII, N. 47, 22 November 1885, p. 322.

- ↑ Raccolta degli atti del governo dittatoriale e prodittatoriale in Sicilia, 1860, Stabilimento tipografico Francesco Lao, Palermo

- 1 2 Christopher Duggan (2000). Creare la nazione. Vita di Francesco Crispi. Laterza.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Rattazzi, Urbano". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 22 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 919. This work in turn cites:

- Rattazzi, Laetitia (1881). Rattazzi et son temps. Paris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - King, Bolton (1899). History of Italian Unity. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

- Rattazzi, Laetitia (1881). Rattazzi et son temps. Paris.

- ↑ Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

- ↑ Fulvio Cammarano, Storia dell'Italia liberale, Roma-Bari, Laterza, 2011

- ↑ Christopher Duggan, Creare la nazione. Vita di Francesco Crispi, Roma-Bari, Laterza, 2000

- ↑ Biografia di Agostino Depretis

- ↑ Il Risorgimento – Enciclopedia Treccani

- ↑ Storia Militare n. 215, Parma 2011, p. 64

- ↑ La Terza Guerra d'Indipendenza

- ↑ Giancarlo Giordano, Cilindri e feluche. La politica estera dell'Italia dopo l'Unità, Roma, Aracne, 2008

- ↑ La Stampa, Thursday, 5 November 1874

- ↑ La Stampa, Sunday, 8 November 1874

- ↑ La Stampa, Monday, 16 November 1974

- 1 2 3 4 Nohlen & Stöver, p1029

- ↑ Flynn, John T. Pre-Fascist Italy: Tax and Borrow and Spend, Mises Institute

- ↑ La rivoluzione parlamentare che segnò la storia d’Italia

- ↑ Nohlen & Stöver, p1028

- 1 2 Nohlen & Stöver, pp1029-1030

- ↑ Nohlen & Stöver, p1049

- 1 2 Nohlen & Stöver, p1039

- ↑ Nohlen & Stöver, p1082

- ↑ Frank J. Coppa, Planning, protectionism, and politics in liberal Italy: economics and politics in the Giolittian age (Catholic University of America Press, 1971.)

.svg.png.webp)