Environmental issues in Indonesia are associated with the country's high population density and rapid industrialisation, and they are often given a lower priority due to high poverty levels, and an under-resourced governance.[1]

Most large palm oil plantations in Indonesia owned by Singaporean rich conglomerates who employ thousands of local native Indonesians.

Issues include large-scale deforestation (much of it illegal) and related wildfires causing heavy smog over parts of western Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore; over-exploitation of marine resources; and environmental problems associated with rapid urbanisation and economic development, including air pollution, traffic congestion, garbage management, and reliable water and waste water services.[1]

Deforestation and the destruction of peatlands make Indonesia the world's third largest emitter of greenhouse gases.[2] Habitat destruction threatens the survival of indigenous and endemic species, including 140 species of mammals identified by the World Conservation Union (IUCN) as threatened, and 15 identified as critically endangered, including the Sumatran orangutan.[3]

History and background

For centuries, the geographical resources of the Indonesian archipelago have been exploited in ways that fall into consistent social and historical patterns. One cultural pattern consists of the formerly Indianized, rice-growing peasants in the valleys and plains of Sumatra, Java, and Bali; another cultural complex is composed of the largely Islamic coastal commercial sector; a third, more marginal sector consists of the upland forest farming communities which exist by means of subsistence swidden agriculture.

To some degree, these patterns can be linked to the geographical resources themselves, with abundant shoreline, generally calm seas, and steady winds favouring the use of sailing vessels, and fertile valleys and plains—at least in the Greater Sunda Islands—permitting irrigated rice farming. The heavily forested, mountainous interior hinders overland communication by road or river, but fosters slash-and-burn agriculture.

Each of these patterns of ecological and economic adaptation experienced tremendous pressures during the 1970s and 1980s, with rising population density, soil erosion, river-bed siltation, and water pollution from agricultural pesticides and off-shore oil drilling.

Marine pollution

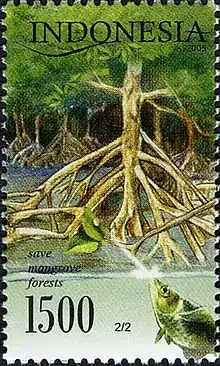

In the coastal commercial sector, for instance, the livelihood of fishing people and those engaged in allied activities—roughly 5.6 million people—began to be imperiled in the late 1970s by declining fish stocks brought about by the contamination of coastal waters. Fishermen in northern Java experienced marked declines in certain kinds of fish catches and by the mid-1980s saw the worst virtual disappearance of the fish in some areas. Effluent from fertiliser plants in Gresik in northern Java polluted ponds and killed milkfish fry and young shrimp. The pollution of the Strait of Malacca between Malaysia and Sumatra from oil leakage from the Japanese supertanker Showa Maru in January 1975 was a major environmental disaster for the fragile Sumatran coastline. The danger of supertanker accidents also increased in the heavily trafficked strait.

The coastal commercial sector suffered from environmental pressures on the mainland, as well. Soil erosion from upland deforestation exacerbated the problem of siltation downstream and into the sea. Silt deposits covered and killed once-lively coral reefs, creating mangrove thickets and making harbour access increasingly difficult, if not impossible, without massive and expensive dredging operations.

Although overfishing by Japanese and American "floating factory" fishing boats was officially restricted in Indonesia in 1982, the scarcity of fish in many formerly productive waters remained a matter of some concern in the early 1990s. As Indonesian fishermen improved their technological capacity to catch fish, they also threatened the total supply.

Water pollution

Indonesia holds at as much as 6% of global freshwater stock which thanks to its rich rainforest and tropical climate. However, Indonesia has been losing its forest every year where in 2018, 440,000 hectares of forest were lost although this figure is lower than 2017.[4] Such deforestation is associated with the reduction of water catchment capacity, as studies have found.[5] Meanwhile, Indonesia's Ministry of National Development Planning (BAPPENAS) reported that 96% of rivers in Jakarta have been polluted,[6] making fresh, clean water even more scarce.

Water pollution is caused by both industrial and domestic waste. Indonesian government has regulated industrial in which companies are required to meet the wastewater standard. Indonesia was also a pioneer in public disclosure of industrial pollution data through a program called Program for Pollution Control, Evaluation and Rating (PROPER)[7] which has been implemented since 1995. PROPER incentivizes industries to disclose their pollution data by giving a rating based on their performance, hence affecting their reputation.[8] This program helps strengthen the existing regulations which require industries to comply with industrial waste management standard.

On the other hand, domestic water pollution is produced by households who dump trash and wastewater from household activities, such as bathing, washing, open defecation, etc., to the surface water. These behaviours are not always realized as the problem will be more apparent when the domestic wastewater has accumulated from all households, and caused eutrophication.[9] The Environment and Forestry Ministry has reported that domestic wastewater as the major river polluter.[10] With a growing population and higher rate urbanization, domestic wastewater will contribute more to the overall water pollution in the country, even in the rural areas where the use of chemical detergents is increasing rapidly.

Both sources of pollution do not only deplete surface water quality, but also the groundwater. The chemical compounds from both industrial and domestic waste can sneak through the soil and when the groundwater is relatively shallow, these contaminants will mix with the clean water.[11] Unless the government regulates domestic wastewater management and ensures a strong law enforcement for industrial waste, the risk of pollution will remain. In addition, information dissemination related to water pollution, albeit required by law, is limited which makes communities vulnerable to the impacts of water pollution.[12]

Air pollution

The 1997 Indonesian forest fires in Kalimantan and Sumatra caused the 1997 Southeast Asian haze. It was a large-scale air quality disaster. The total costs are estimated at US$9 billion to health care, air travel and business. In 2013, the air quality in Singapore sank to its lowest in 15 years due to smoke from Sumatran fires. Singapore urged Indonesia to do more to prevent illegal burning.[13]

Deforestation and agricultural pollution

A different, but related, set of environmental pressures arose in the 1970s and 1980s among the rice-growing peasants living in the plains and valleys. Rising population densities and the consequent demand for arable land gave rise to serious soil erosion, deforestation due to the need for firewood, and depletion of soil nutrients. Runoff from pesticides polluted water supplies in some areas and poisoned fish ponds. Although national and local governments appeared to be aware of the problem, the need to balance environmental protection with pressing demands of a hungry population and an electorate eager for economic growth did not diminish.

Major problems faced the mountainous interior regions of Kalimantan, Sulawesi and Sumatra. These problems included deforestation, soil erosion, massive forest fires, and even desertification resulting from intensive commercial logging—all these threatened to create environmental disasters. In 1983 some 30,000 km2 (12,000 sq mi) of prime tropical forest worth at least US$10 billion were destroyed in a fire in Kalimantan Timur Province.

The disastrous scale of this fire was made possible by the piles of dead wood left behind by the timber industry. Even discounting the calamitous effects of the fire, in the mid-1980s Indonesia's deforestation rate was the highest in Southeast Asia, at 7,000 km2 (2,700 sq mi) per year and possibly as much as 10,000 km2 (3,900 sq mi) per year. Although additional deforestation came about as a result of the government-sponsored Transmigration Program (transmigrasi) in uninhabited woodlands, in some cases the effects of this process were mitigated by replacing the original forest cover with plantation trees, such as coffee, rubber, or palm.

In many areas of Kalimantan large sections of forest were cleared, with little or no systematic effort at reforestation. Although reforestation laws existed, they were rarely or only selectively enforced, leaving the bare land exposed to heavy rainfall, leaching, and erosion. Because commercial logging permits were granted from Jakarta, the local inhabitants of the forests had little say about land use, but in the mid-1980s, the government, through the Department of Forestry, joined with the World Bank to develop a forestry management plan. The efforts resulted in the first forest inventory since colonial times, seminal forestry research, conservation and national parks programs, and development of a master plan by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations.

The use of fires to clear land for agriculture has contributed to Indonesia being the world's third largest emitter of greenhouse gases, after China and the United States.[14] Forest fires destroy carbon sinks in old-growth rainforests and peatlands. Efforts to curb carbon emissions, known as Reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD), include monitoring of the progression of deforestation in Indonesia and measures to increase incentives for national and local governments to halt it. One such monitoring system is the Center for Global Development's Forest Monitoring for Action[15] platform, which currently displays monthly-updating data on deforestation throughout Indonesia.

Indonesia had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 6.6/10, ranking it 71st globally out of 172 countries.[16]

Climate change

.jpg.webp)

Due to its geographical and natural diversity, Indonesia is one of the countries most susceptible to the impacts of climate change.[17] This is supported by the fact that Jakarta has been listed as the world's most vulnerable city, regarding climate change.[18][19] It is also a major contributor as of the countries that has contributed most to greenhouse gas emissions due to its high rate of deforestation and reliance on coal power.

Made up of more than 17,000 islands and with a long coastline, Indonesia stands particularly vulnerable to the effects of rising sea levels and extreme weather events such as floods, droughts, and storms. Its vast areas of tropical forests are vital in balancing out climate change by taking in carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.[20] Projected impacts on Indonesia's agricultural sector, national economy and health are also significant issues.

Indonesia has committed to reducing its emissions within the framework of the Copenhagen Accord and Paris Agreement. Despite the significant impacts of climate change on the country, surveys show that Indonesia has a high proportion of climate change deniers.Emissions

Greenhouse gas emissions in Indonesia result from seasonal fires, deforestation, and the burning of peat. Depending on the severity of seasonal fires, Indonesia may range from the third to the sixth largest annual emitters.[21]

Greenhouse gas emissions produced by Indonesia represent a significant fraction of the world total. Indonesia has been called the "most ignored emitter" that "could be the one that dooms the global climate."[21] It is "one of the largest emitters of greenhouse gases" (GHG).[22] 2013 measurements show Indonesia's total GHG emissions were 2161 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent which totaled 4.47 percent of the global total.[23] In 2014, it was ranked eighth highest on the list of countries by greenhouse gas emissions.

During the 21st century, an area of forest roughly equivalent to the size of the US state of Michigan (92,000 square miles) has been cut down, mainly in order to expand palm oil plantations.[24]

Indonesia plans to double its consumption of coal by 2027 in order to build new coal power plants.[24]

1997 fires

The 1997 group of forest fires in Indonesia that lasted well into 1998 were probably among the two or three, if not the largest, forest fires group in the last two centuries of recorded history.

In the middle of 1997 forest fires burning in Indonesia began to affect neighbouring countries, spreading thick clouds of smoke and haze to Malaysia and Singapore. Then Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir bin Mohamad searched desperately for a solution, and based on a plan by the head of the Malaysian fire and rescue department sent a team of Malaysian firefighters across to Indonesia under code name Operation Haze. This is to mitigate the effect of the Haze to Malaysia economy. The value of the Haze damage to Malaysian GDP is estimated to be 0.30 per cent.

Seasonal rains in early December brought a brief respite but soon after the dry conditions and fires returned. By late 1997 and early 1998 Brunei, Thailand, Vietnam, the Philippines and Sri Lanka had also felt the haze from the smoke of the forest fires. By the time the 1997–98 forest fires were finally over some 8 million hectares of land had burned while countless millions of people suffered from air pollution.2010 fires

The 2010 Southeast Asian haze was an air pollution crisis which affected many Southeast Asia countries such as Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore during the month of October in 2010.[25]

This occurred during the dry season in October when forest fires were being illegally set off by Indonesian smallholders residing in the districts of Dumai and Bengkalis, in the Riau province of Sumatra.[26] These farmers use the slash and burn method to clear off land rapidly for future farming opportunities.[27] The number of fires in Sumatra peaked on 18 October, with 358 hotspots.[25]

2015 fires

In 2015, Indonesia had severe fires that lasted for almost two months. Peat was the main fuel source. An El Niño had caused a particularly dry season that worsened the situation.[28] The fires released enough greenhouse gasses for Indonesia to produce more daily emissions than the United States for 38 days.

Mining and the environment

Buyat Bay was used by PT Newmont Minahasa Raya from 1996 to 2004 as a tailings dumping ground for its gold mining activities.[29]

Natural environmental hazards

Natural hazards include occasional floods, severe droughts, tsunamis, earthquakes, volcanoes and forest fires. Human activities can help cause or exacerbate these hazards. For Indonesia, coastal flooding and the rising sea level are viewed to be among the major risks posed by climate change.[30]

Notable environmental issues

Buyat Bay has been used by PT Newmont Minahasa Raya since 1996 as a tailings dumping ground for its gold mining activities.

- Grasberg mine

- Blast fishing in Indonesia

- Deforestation in Borneo

- Water supply and sanitation in Indonesia

- Citarum River, one of the world's most polluted rivers[31]

Environmental education

A 2019 survey by YouGov and the University of Cambridge concluded that at 18%, Indonesia has "the biggest percentage of climate deniers, followed by Saudi Arabia (16 percent) and the U.S. (13 percent)."[24]

Climate education is not a part of the school curriculum.[24][32]

Government policies

The Indonesian government has voluntarily committed to a minimum 26 percent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2020 and by 29 percent by 2030.[33] However, Indonesia has been ineffective in implementing policies to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement. As of 2018, government policies were increasing emissions. These policies include the construction of 100 coal-fired power plants, the expansion of palm oil production, and the increase of biofuel consumption.[21]

Indonesia developed climate policy related to land use and forestry emissions. A moratorium on clearing of primary forests and peat lands was extended from two to four years.[34]

The Indonesian government is seeking to reduce poverty by 4 percent by 2025, but strong climate policies could make this impossible to achieve. International assistance could enable Indonesia to reduce its emissions by an estimated 41 percent by 2030.[22]

In December 2021 a court in Indonesia stopped two companies from logging forests for palm oil plantations. This corresponds to the pledge of the government to stop such logging for halt deforestation.[35]

See also

References

![]() This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Country Studies. Federal Research Division.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Country Studies. Federal Research Division.

- 1 2 Jason R. Miller (30 January 1997). "Deforestation in Indonesia and the Orangutan Population". TED Case Studies. Retrieved 14 August 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Higgins, Andrew (19 November 2009). "A climate threat, rising from the soil". The Washington Post. Retrieved 11 December 2009.

- ↑ Massicot, Paul. "Animal Info – Indonesia". Animal Info – Information on Endangered Mammals. Retrieved 14 August 2007.

- ↑ Wijaya, A., Samadhi, T.N., Juliane, R. (24 July 2019) Indonesia Is Reducing Deforestation, but Problem Areas Remain. WRI Indonesia.

- ↑ Booij, M.J., Schipper, T.C., and Marhaento, H. (2019). "Attributing Changes in Streamflow to Land Use and Climate Change for 472 Catchments in Australia and the United States". Water. 11 (5): 1059. doi:10.3390/w11051059.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Jakarta's river water severely polluted: Bappenas. The Jakarta Post. 2 February 2018.

- ↑ Program for Pollution Control, Evaluation and Rating (PROPER)

- ↑ Makarim, N., Ridho, R., Sarjanto, A., Salim, A., Setiawan, M.A., Ratunanda, D., Wawointana, F., Dahlan, R., Afsah, S., Laplante, B., and Wheeler, D. (1995). What Is Proper? Reputational Incentives for Pollution Control in Indonesia. PROPER-PROKASIH, BAPEDAL, PRDEI and World Bank.

- ↑ Chislock, M.F., Doster, E., Zitomer, R.A. and Wilson, A.E. (2013). "Eutrophication: Causes, Consequences, and Controls in Aquatic Ecosystems". Nature Education Knowledge. 4 (4): 10.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Air Sungai di Indonesia Tercemar Berat. National Geographic Indonesia. 2 May 2016.

- ↑ Fauzi, D., Widyapratami, H., Wicaksono, S., and Chandra, A. (10 May 2018) How to Tackle Domestic Wastewater Pollution? Start from the Upstream. WRI Indonesia.

- ↑ Excell, C., Moses, E. (2017). Thirsting for Justice: Transparency and Poor People’s Struggle for Clean Water in Indonesia, Mongolia, and Thailand. Working Paper. World Resources Institute (WRI).

- ↑ "Singapore pollution soars as haze from Indonesia hits air quality," The Guardian, 19 June 2012

- ↑ The Washington Post, 19 November 2009

- ↑ de Nevers, Michele. Forest Monitoring for Action. cgdev.org

- ↑ Grantham, H. S.; Duncan, A.; Evans, T. D.; Jones, K. R.; Beyer, H. L.; Schuster, R.; Walston, J.; Ray, J. C.; Robinson, J. G.; Callow, M.; Clements, T.; Costa, H. M.; DeGemmis, A.; Elsen, P. R.; Ervin, J.; Franco, P.; Goldman, E.; Goetz, S.; Hansen, A.; Hofsvang, E.; Jantz, P.; Jupiter, S.; Kang, A.; Langhammer, P.; Laurance, W. F.; Lieberman, S.; Linkie, M.; Malhi, Y.; Maxwell, S.; Mendez, M.; Mittermeier, R.; Murray, N. J.; Possingham, H.; Radachowsky, J.; Saatchi, S.; Samper, C.; Silverman, J.; Shapiro, A.; Strassburg, B.; Stevens, T.; Stokes, E.; Taylor, R.; Tear, T.; Tizard, R.; Venter, O.; Visconti, P.; Wang, S.; Watson, J. E. M. (2020). "Anthropogenic modification of forests means only 40% of remaining forests have high ecosystem integrity - Supplementary Material". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 5978. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.5978G. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19493-3. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7723057. PMID 33293507.

- ↑ "Wayback Machine" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 October 2019. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ↑ "Climate change: the cities most at risk". The Week UK. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ↑ "Photos: Where once were mangroves, Javan villages struggle to beat back the sea". Mongabay Environmental News. 3 July 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ↑ Chiappetta Jabbour, Charbel Jose; Seuring, Stefan; Lopes de Sousa Jabbour, Ana Beatriz; Jugend, Daniel; De Camargo Fiorini, Paula; Latan, Hengky; Izeppi, Wagner Colucci (15 June 2020). "Stakeholders, innovative business models for the circular economy and sustainable performance of firms in an emerging economy facing institutional voids". Journal of Environmental Management. 264: 110416. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110416. ISSN 0301-4797. PMID 32217311. S2CID 214679425.

- 1 2 3 Coca, Nithin (28 March 2018). "The Other Country Crucial to Global Climate Goals: Indonesia". The Diplomat. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- 1 2 Piesse, Mervyn (18 September 2018). "Indonesian Climate Change Policies: Striking a Balance between Poverty Alleviation and Emissions Reduction". Future Directions International. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ↑ "Greenhouse Gas Emissions Factsheet: Indonesia | Global Climate Change". www.climatelinks.org. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 Dickinson, Leta (10 May 2019). "With sea levels rising, why don't more Indonesians believe in human-caused climate change?". Grist. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- 1 2 National Environment Agency (2010). "Annual Weather Review 2010" (PDF). Review of Weather Conditions in 2010. 1: 2–5.

- ↑ "Worst haze from Indonesia in 4 years hits neighbors hard". Reuters. 21 October 2010. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ↑ "Harvard-Columbia study finds that 2015 haze in Indonesia likely caused 100,300 premature deaths". Mighty Earth. 18 September 2016. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ↑ Plumer, Brad (30 October 2015). "How Indonesia's fires became one of the world's biggest climate disasters". Vox.

- ↑ Mamonto, PDL, Sompie, CED & Mekel, PA (2012) "Sustainable development for post-closure – a case study of PT Newmont Minahasa Raya", in AB Fourie & M Tibbett (eds), Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Mine Closure, Australian Centre for Geomechanics, Perth, pp. 279–293. ISBN 978-0-9870937-0-7

- ↑ Overland, Indra et al. (2017) Impact of Climate Change on ASEAN International Affairs: Risk and Opportunity Multiplier, Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI) and Myanmar Institute of International and Strategic Studies (MISIS).

- ↑ Collins, Nancy-Amelia (5 December 2008). "ADB Gives Indonesia $500 Million to Clean Up World's Dirtiest River". voanews.com. Archived from the original on 2 July 2010. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ↑ Putrawidjaja, Mochamad (2008). "Mapping Climate Education in Indonesia". Jakarta: British Council.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Indonesia pledges to cut carbon emissions 29% by 2030, The Guardian, 2 September 2015

- ↑ "Climate Change – Indonesia". World Resources Institute. 26 September 2013. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ↑ Beo Da Costa, Agustinus; Ungku, Fathin (7 December 2021). "Indonesia Court Rejects Bid to Reinstate Palm Oil Permits in Papua". US news. Retrieved 9 December 2021.