Introduction

This article traces the reaction of allied generals Douglas Haig and Philip Pétain to Operation Michael, the first assault by Germany during the German Spring Offensive against the Western Front on March 21, 1918. Having achieved peace and complete victory in the East by the Russian Revolution, the overthrow of the legitimate Russian Government and its replacement by a Communist one, and the Brest-Litovsk Peace Treaty, the Kaiser planned to secretly move as many of his combat divisions as possible from Germany's Eastern Front to her Western Front during the winter of 1917–1918, for a final, climatic, assault against France to end the war. The attack nearly succeeded, and if it wasn't for the appointment of General Ferdinand Foch as Allied Supreme Commander on March 26, there is a good chance that it could have.

Background

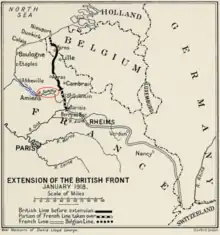

The World War was not going well for the British and French at the beginning of 1918, with the British just coming off the costly Flanders offensive, the French reeling with unhappiness in the trenches after the Nivelle offensive, and American troops slow in arriving to France. General Haig of the British Expeditionary Force (B.E.F.), knowing the war was one of attrition, requested to continue his costly assaults in the Fall of 1917 and Spring of 1918 to wear down the German Army. However, Prime Minister Lloyd George had no troops to give him unless he asked for another round of the draft and greater sacrifices from the public by expanding conscription (lowering the minimum draft age to 18, the maximum age to 55, and drafting the Irish) or diverting personnel from critical war industries. General Haig's requests to bring the B.E.F. up to full strength (the Flanders Offensive reduced his battalions per division from 12 to 9) were denied, the Prime Minister thinking he would just have to make do until the Americans arrive in force, and for an Allied offensive to take place sometime in 1919. In the meantime, Prime Minister Clemenceau, fearing most of his army would be demobilized in nine months due to drafts ending, asked the British to take over an additional 25 miles of the Front from the French, which they did in January 1918 (see Map #3). The area was occupied by the British Fifth Army, under the command of General Hubert Gough. Known as "The Fifth Army Front", it was poorly prepared for defense by the French, its natural barrier, the Oise River, had dried over the winter, and it was to receive the spearhead of the German assault.

The Assault on the Western Front

In the early morning hours of March 21, 1918, German artillery rained down on the Western Front. The spearhead of a massive German assault of nearly 200 divisions then hit and broke the Allied line right at its weakest point.[1] The exact area of the attack was predicted in January by the Supreme War Council,[2][3] the Prime Ministers of England and France had ordered a reserve of 30 divisions to deal with it, but generals Pétain and Haig ignored the order. When this was discovered on March 15, it was too late to fire them, so they had their way.[4] The Germans had been preparing for a massive attack for months. When it occurred, it caught the Allies by surprise. Due to good deception, in France General Petain was convinced it was a diversionary attack, that the main attack would be made in the middle of his sector (Champagne), 50 miles to the south, and in England Prime Minister Lloyd George received reassuring messages on the first two days of the battle that the attack might just be "a big raid".[5][6] Also, the General Reserve, that would have been available if General's Haig and Petain had followed their orders and contributed the soldiers, would have been deployed right where it was needed, and it would have been ready to respond. However, at the time of the attack, General Haig's reserve divisions were deployed way in the north (see Map #1, red circle), near the Channel Ports, General Pétain refused to use his reserves in Champagne (blue circle), because he thought the attack would be there, which only made his divisions near Switzerland (orange and yellow circles) available for deployment.[7] This meant it would take time, not weeks but in some cases months, to move them into position (the original 30 division reserve needed a three-month lead time to be put into place). Meanwhile, within days of the assault the Front had been breached along a 50-mile line, on March 24 General Petain issued orders for his army to retreat and cover Paris, on March 25 General Haig drafted an order for the British to retreat towards the English Channel, and the Germans were on the verge of winning the war (see Map #2).[8][9]

Allied Troop Movements

The English and French

The British Fifth Army bore the brunt of the German assault. Led by General Hubert Gough, it had taken over a section of the French Front during the winter, and it was the weakest part of the British line (see Map #3). Also, General Haig kept most of his reserve divisions near the English Channel (see Map #1, red circle), allowing Gough to make do with 17 divisions on the line, and 2 (from GHQ) in his rear. This army was attacked by 50 German divisions (thought to have been 81 by General Haig), and outnumbered three to one it could not hold. The thought of a permanent break between the English and French was serious, and due to bad luck, Allied leadership in Paris and London didn't know this was the big attack they had feared until March 23. To meet the threat, General's Petain & Haig a month earlier (on February 22) arranged a verbal agreement to mutually support one another.[10][11]

In the evening of March 21 and early March 22, General Haig asked General Pétain for 3 divisions to support Gough. His request was immediately granted, with the French Fifth Corp (3 divisions under the command of General Pelle, comprising half of the Third Army), ordered to the breach to reinforce the English right flank.[12] These troops were transported in lorries and started arriving on March 23.[13] In a confidential report to General Haig after the battle, General Gough wrote that on the first day of the attack, "I could only expect one division at a time, at intervals of 72 hours (3 days), and that the first to arrive could not be expected for 72 hours...and...the French division...would not arrive any faster."[14][15] Gough was referring to the British 8th Division, the only one General Haig could spare from his reserve, and the nearby French divisions of General Pétain's Third Army that were strategically positioned behind the Front in the French sector, but close to the English. Due to urgency from the attack, by March 26 seven French divisions and the one English division, coming on piecemeal and without their artillery, were fighting in the British Fifth Army Front.[16]

On the afternoon of March 22, General Haig asked for 3 more divisions, and General Pétain responded by ordering his entire Third Army (3 more divisions) under General Humbert to the breach.[17] In the evening, convinced that he was under attack by 81 German divisions, General Haig asked General Pétain for his entire Fifth Army (20 more divisions). He also asked the French to take over the English sector south of the Somme (See Maps #3 & 4), and for General Pétain to take over Gough's Fifth Army. However, General Pétain was certain only 26 divisions were attacking Haig, and the other 55 were about to attack him.[18] For this reason, he spared his reserves around Champagne, and he ordered his First Army, stationed much further south, to proceed to the breach. This delayed the arrival of its six divisions. General Pétain also agreed to take over the entire area of the breach, and he placed its command (now 12 divisions on the move) under General Fayolle.[19]

On March 23, Gough's Fifth Army, and the British Third Army on its left, were being swept away. Prime Minister Clemenceau visited General Pétain twice at French GQG in Compiègne, and returned both times telling President Poincaré that the government must evacuate Paris.[20] Also, as the first French reserves started arriving at the breach by battalion, they were immediately thrown in. At 4pm, Haig and Pétain met at Dury Town Hall. Here, General Haig again requested 20 French divisions to be concentrated around Amiens, along the Somme River, to prevent his encirclement by the Germans and to secure a way to the Channel Ports (see Map #2). General Pétain, who had 30 divisions left in his reserve, refused. He wanted to keep this force to cover Paris. At this point, national interests superseded those of the Allies as a whole, and both sides planned to leave the Front open to the Germans.[21][22]

On March 24, the French reserves arriving on scene couldn't hold a line at the Front or their link with the English. Keeping his reserves in Champagne, during the day General Pétain ordered 6 more divisions (18 total) from further south in his line (south of Champagne) to be moved to the rear of the breach to thwart German advances inland. As earlier, this delayed their arrival. By the evening, the separation between the French and English armies was so bad that General Pétain ordered General Fayolle to hold his link with the French all costs, and to link with the English only "if possible". Pétain then visited General Haig at his Dury headquarters at 11pm, to tell him that if he continued to pull away from the French, he would be forced to draw back his own armies to cover Paris. In fact, orders for this were issued.[23] General Haig, still thinking the B.E.F. was under attack by the entire German army, questioned General Pétain as to whether or not he would abandon him. Petain answered, "It is the only thing possible".[24][25]

After lunch at French headquarters on March 25, French Minister of Munitions Louis Loucher estimated the chances of an Allied defeat at 90%; General Petain corrected him and said it was 96%.[26][27] Pétain then told Loucheur that Prime Minister Clemenceau should be urged to ask for peace.[28] Under orders from Paris, in the afternoon on an easel in his office, General Pétain was arranging the redeployment of his armies to protect the capital. The situation bottomed out as Pétain envisioned the separation of the French and British armies, with the British falling back to Calais to defend its supply routes near the English Channel, and the French having to extend its army to the ocean somewhere behind the British lines. This would result in a series of battles north of Paris, and a French loss would mean Paris would be abandoned, with very serious consequences for the country.[29] To prevent this, it was necessary to defend the capital immediately, and orders for this were issued.[30]

The Americans

In the morning of March 25, a call was placed from Compiègne to General Pershing, asking him for all the help he could give. Pershing said, "I'm coming over." Upon hearing this, General Barescut at GQG said, "Mon Dieu, why doesn't he just use the telephone?" Pershing was called again, and he told the American liaison officer, "You tell the general I'm coming over right now!" The French waited throughout the day, General Pétain even postponed dinner, but still nothing. Finally, at 10:45pm Pershing arrived, delayed by traffic and refugees. In a meeting where Pershing said, "everyone talked fast", he agreed to loan General Pétain his 4 American divisions (equivalent to 8 French divisions). Pétain would substitute them for his own, and transfer his veteran divisions into the breach.[31] However, these troops would also come from further south in the line, below Verdun, and would take time to employ. Of the 4 American divisions, one went directly into battle with the English, and the three less trained ones took their place in the French line. With American help, General Pétain had a total of 24 divisions to send into action. The big handicap was time. As a rule of thumb, it took 2 days by train to move a single division, but with trucks, hopefully the time could be sped up. The mass movement of 24 divisions could take two months, and this did not include guns (heavier support weapons, like artillery), which took much longer to move. Certainly, this delay weighed heavily on the minds of General's Pétain and Haig, and Prime Minister Clemenceau, after the three teamed up to oppose the formation of an Allied General Reserve they had agreed to back in January, which would have been in the right place at the right time to stop the attack.

Follow Up

Fortunately for the Allies, a series of secret World War I meetings were held which culminated in the selection of French General Ferdinand Foch as supreme commander of the Western Front. These higher level meetings, held in Paris, Compiègne (French GQG Headquarters), and Doullens Town Hall, put an end to any idea of a retreat, and brought the war to an early conclusion. The exact Allied troop positions on the morning of March 26, 1918 are noted on a map made by General Foch at the Doullens Conference, and published in his autobiography in 1930 (See Map #4). Note that all of the divisions south of the Avre River are French (debarking), the general position of the British V Army, which retreated northwest from where the French are (the outstretched hand), and the broken line West of Amiens, along the Somme, where General Haig requested 20 French Divisions to cover the flank of the B.E.F., "which must fight its way slowly back covering the Channel Ports".[32] Not mentioned is the British III Army, which folded its right along the (North/South dividing) line of the Somme after the V Army retreat, was massing troops there to defend against a German attack, and had conditional plans to fall back to Arras, if necessary, to form its line there (See Map #3).

Footnotes

- ↑ Mott, Bentley, The Memoirs of Ferdinand Foch, pg. 284

- ↑ Amery, Leopold, "My Political Life, Vol. II", pgs. 138-139

- ↑ Parliament Meeting, 9 April 1918, Lloyd George comments

- ↑ Mott, pgs. 285-286

- ↑ Lloyd George, David, "War Memoirs, Vol. V", pg. 380

- ↑ UK National Archives, CAB 23-5, pg. 360 of 475

- ↑ Amery, pg. 139

- ↑ Mott, pgs. 291-293

- ↑ Lloyd George, pgs. 387-388

- ↑ Wright, Peter E. "At the Supreme War Council", pg. pg. 85

- ↑ Aston, George, "The Biography of the Late Marshal Foch", pg. 283

- ↑ Liddell-Hart, "Foch: The Man of Orleans", pg. 267

- ↑ Weygand, Maxime, "Memoires, Vol. I", pg. 471

- ↑ Wright, pgs. 115-116

- ↑ Wright, pgs. 194-195

- ↑ Wright, pg. 145

- ↑ Mott, pg. 290

- ↑ Liddell-Hart, pg. 268

- ↑ Weygand, pg. 473

- ↑ Huddleston, Sisley, "Poincaré: A Biographical Portrait", pg. 82

- ↑ Mott, pgs. 292-293

- ↑ Weygand, pg. 473

- ↑ Edmonds, James, "History of the Great War, Vol. VIII", pgs. 448-450

- ↑ UK National Archives, CAB 23-5, pg. 422 minute 1, par 2, of 475

- ↑ Edmonds, pg. 450

- ↑ Loucheur, Louis, "Carnets Secrets", pg. 179

- ↑ Reid, Walter, "Five Days From Defeat", pg. 177

- ↑ Loucheur, pg. 179

- ↑ Loucheur, pg. 54

- ↑ Edmonds, pgs. 448-450

- ↑ Smythe, Donald, "Pershing, General of the Armies", pgs. 98-99

- ↑ Lloyd George, pg. 388

References

- Mott, Bentley, The Memoirs of Marshall Foch, London: Heinemann, 1931

- Amery, Leo, My Political Life, Vol. II, War and Peace (1914-1929), London: Huchinson, 1953

- Parliament Minutes: Link

- Lloyd George, David, War Memoirs of David Lloyd George, Vol V, Boston: Little Brown, 1936

- UK National Archives (World War I section)

- Wright, Peter, At The Supreme War Council, New York & London: Putnam, 1921

- Aston, George, The biography of the late Marshal Foch, New York: MacMillan, 1929

- Liddell-Hart, B.H., Foch: The Man of Orleans, Boston: Little Brown, 1931

- Weygand, Maxime, "Memoires, Vol I", Paris: Flammarion, 1953

- Huddleston, Sisley, Poincare: A Biographical Portrait, Boston: Little Brown, 1924

- Edmonds, Sir James E, History of the Great War, Vol VIII, Military Operations, the March Offensive, 1918, London: MacMillan, 1935

- Loucheur, Louis, "Carnets Secrets", Brussels: Brepols, 1962

- Reid, Walter, "Five Days From Defeat", Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2017

- Smythe, Donald, "Pershing, General of the Armies", Bloomington: Indiana University, 1986

External Links

- Internet Archive (Please sign up to view footnote and reference details): Link

- UK National Archives: (World War I section)

- Parliament Minutes: Link