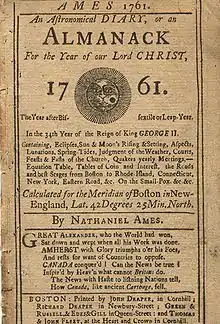

Cover of Ames Almanack in 1761 | |

| Author | Nathaniel Ames (1725-1764) Nathaniel Ames (1764-1775) |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Almanac |

| Published | 1725-1775 |

Ames' Almanack (almanac) was the first almanac printed in the British North American colonies. While Benjamin Franklin's Poor Richard's Almanack is the one often mentioned in contemporary history classes, at the time Ames' Almanack enjoyed a much larger readership. Franklin's publication had a circulation of 10,000 copies, while Ames' Almanack had a circulation of 60,000.[1]

Authors

Nathaniel Ames, a second generation colonial American, established and wrote Ames' Almanac.[2] Ames was only seventeen when the first almanac was printed. The family also owned Ames Tavern and often advertised the establishment in the almanac.[3] Upon Ames' death in 1764, his son, also Nathaniel, began writing the almanac. He continued to print the almanac until 1775.[4] The younger Nathaniel strongly supported the antifederalist cause, which contrasted to his brother, the prominent Federalist congressman Fisher Ames. Based on a correspondence between Ames and Roger Sherman, it appears that Sherman wrote some of the mathematical portions of the almanac in 1753.[5]

Intellectual property

With no real intellectual property enforcement, readers frequently copied the almanac for others. This led to bickering among printers as to who published the genuine edition of Ames' Almanack forcing Ames to certify by card as to the original version.[6]

Legacy

Ames wrote during a time of a growing national concept of 'America' and not that of the traditional political conception of 'state' (in Ames' case Massachusetts). The growing conception of a national 'American' entity was reflected and propagated by the annual almanacs.[7] By 1775, the almanac published a manual on how to make gunpowder so that every man could supply himself "with a sufficiency of that commodity."[8] As the American Revolution started in 1775, there was a severe gunpowder shortage in Boston. As George Washington wrote to Congress, the Continental Army was "exceedingly destitute" of the material.[9]

Ames took a stand on the religious Great Awakening running through the colonies in the early 18th century. The Great Awakening challenged the traditional authority of the congregationalist church. George Whitefield, an English evangelist, created controversy in the colonies with his Great Awakening sermons. In 1741, Ames satirized critics of Whitefield in "To the Scoffers at Mr. Whitefield's Preaching." Four years later, Whitefield came to Ames' hometown of Dedham to give one of his sermons.[10]

The same format used in Ames' Almanack was implemented by the Old Farmer's Almanac the popular annual publication in existence since 1792. This includes the following: page headings with the corresponding zodiac sign; left margin noting movable feasts, lines from a poem relevant to that month; phases of the moon; weather predictions; and anniversaries.[11]

Some early colonists used the blank pages of the almanac to keep personal diaries. Their memories are interlaced within the annual almanacs. The American Antiquarian Society collection in Worcester, Massachusetts holds at least two of these diaries, including that of Reverend Thomas Balch (1759).[12] Ebenezer Gay, a pastor at the Church at Hingham in Hingham, Massachusetts similarly recorded his visits to Boston and days of prayer in his copy of the Ames Almanack.[13]

References

- ↑ Jorgenson, Chester E. (Dec 1935). "The New Science in the Almanacs of Ames and Franklin". The New England Quarterly. 8 (4): 555–556. doi:10.2307/360361. ISSN 0028-4866. JSTOR 360361.

- ↑ Drake, Samuel, ed., New England Historical and Genealogical Register, New England Historic Genealogical Society, p. 255.

- ↑ Earle, Alice Morse; Cairns Collection of American Women Writers (1900). Stage-coach and Tavern Days. The Macmillan Company. pp. 164, 167.

- ↑ Stowell, Marion Barber, Early American Almanacs; the Colonial Weekday Bible: The Colonial Weekday Bible, Ayer Publishing, 1977, p. 72.

- ↑ Hamm, Margherita Arlina (1902). Builders of the Republic. J. Pott. pp. 153.

- ↑ Tract. Western Reserve and Northern Ohio Historical Society, Bernard Shaw Society. 1888. p. 473.

- ↑ Sidwell, Robert T (Autumn 1968). ""Writers, Thinkers and Fox Hunters". Educational Theory in the Almanacs of Eighteenth-Century Colonies". History of Education Quarterly. History of Education Society. 8 (3): 279. doi:10.2307/367428. ISSN 0028-4866. JSTOR 367428.

- ↑ Winsor, Justin (1888). Narrative and Critical History of America. Houghton, Mifflin and company. p. 118.

- ↑ Volo, James M. (2003). Daily life during the American Revolution. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 151–152. ISBN 978-0-313-31844-3.

- ↑ Stowell, Marion Barber (Fall 1983). "The Influence of Nathaniel Ames on the Literary Taste of His Time". Early American Literature. University of North Carolina Press. 18 (2): 133. ISSN 0012-8163.

- ↑ Morison, Samuel Eliot and S. E. Morison, Squire Ames and Doctor Ames, The New England Quarterly, Vol. 1, No. 1 (Jan., 1928), pp. 7.

- ↑ Williams, Julie Hedgepeth (1999). The Significance of the Printed Word in Early America: Colonists' Thoughts on the Role of the Press. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-313-30923-6.

- ↑ Lacey, Barbara E. (Summer 1991). "Gender, Piety, and Secularization in Connecticut Religion, 1720-1775". Journal of Social History. Peter N. Stearns. 24 (4): 814. doi:10.1353/jsh/24.4.799. ISSN 0022-4529.