| An Lushan rebellion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

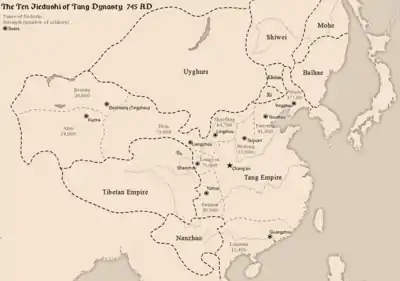

Map of military movements during the An Lushan rebellion | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Tang dynasty Uyghur Khaganate Supported by: | Yan dynasty | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Tang Xuanzong # Tang Suzong # Tang Daizong Feng Changqing Gao Xianzhi Geshu Han Guo Ziyi Li Guangbi Zhang Xun Li Siye (DOW) Pugu Huai'en Yu Chao'en Yan Zhenqing Hun Jian Li Baoyu |

An Lushan X An Qingxu Shi Siming X Shi Chaoyi Zhang Xiaozhong Wang Wujun Xue Song Zhang Zhongzhi Li Huaixian Tian Chengsi Tian Shengong (defected) Gao Juren (mutinied and attempted to defect) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| c. 600,000–700,000 at peak | c. 200,000–300,000 at peak | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Heavy but uncertain: see § Death toll | |||||||

The An Lushan rebellion was an eight-year civil war (from 755 to 763 AD) during the mid-point of the Tang dynasty that started as a commandery rebellion against the Imperial Government, attempting to overthrow and replace it with the rogue Yan dynasty. The more commonly referred term Ān-Shǐ is used to recognize the two families that led the rebellion, originally by An Lushan, a fangzhen (a system of autonomous military districts during Medieval China) general officer and jiedushi of the Taiyuan Commandery who led the rebellion for two years before he was assassinated by his son An Qingxu. Two years after An Qingxu's ascension, Shi Siming, the governor of Pinglu Commandery and a close ally to An Lushan, violently usurped the leadership and killed An Qingxu. Shi Siming ruled for two years, but in turn fell victim to patricide by his own son Shi Chaoyi, who ruled for another two years before the rebellion was finally quelled by Tang loyalists. The rebellion is also known in Chinese historiography either as the An–Shi rebellion, An–Shi Disturbances (simplified Chinese: 安史之乱; traditional Chinese: 安史之亂; pinyin: Ān Shǐ zhī luàn) or Tianbao Chaos (天寶之乱).

The rebellion began in the 14th year of the Tianbao era (755 AD), and its overt phase began on December 16 (November 9 on the traditional lunisolar calendar)[1] when An Lushan mobilized his army and marched to Fanyang, and ended when the Yan dynasty fell on 17 February, 763 AD[2] (although the extended effects lasted past this), spanning the reigns of three Tang emperors (Emperor Xuanzong, Suzong and Daizong). There were also other anti-Tang rebel forces, especially those in An Lushan's base area in Hebei, as well as Sogdian forces and other opportunist parties who took advantages of the chaos.

The rebellion was an important turning point in the history of Medieval China, as the military activities and associated combat deaths caused significant population loss from famine, population displacements and large-scale infrastructure destruction, significantly weakening the Tang dynasty, collapsing the prestige of the Tang emperors as the Khan of Heaven and leading to the permanent loss of the Western Regions. It was a direct cause of Tang dynasty's decline, and led to rampant regional warlord secessionism during the latter half of the dynasty that continued into the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period for nearly a century after Tang's demise, and the fear of repeating Tang's commandery secessionism also led the Song dynasty that followed to distrust and oppress prominent military commanders even when invaded by hostile foreign states such as Liao, Western Xia and Jin. It also triggered the long-term decline of the Guanzhong region, which had then been a political and economic heartland of China at least since the Han dynasty, and the economic center of China had shifted towards the Jiangnan region afterwards.

Background

Political

Beginning in 742, Eurasia entered a 13-year period of major political turmoil, with the regional empires generally suffering "a major rebellion, revolution, or dynastic change."[3] In this year the Second Turkic Khaganate of the eastern Eurasian Steppe was overthrown and then replaced by Sogdian-influenced Uighur rulers.[3] This was apparently the first of several revolutionary events either led by or intimately connected with the merchants and tradespeople involved with the international commerce often referred to as the Silk Road.[4] In 747, the Abbasids began their rebellion against the Umayyad Caliphate in Merv, Khurasan, resulting in the proclamation of a new Abbasid Caliph in about 750.[5] This rebellion also seems to have been organized by merchants and persons identifying themselves as merchants.[5]

The western expansion of the Tang Empire was checked in 751 by the defeat of a large expeditionary force led by General Gao Xianzhi in the Battle of Talas in the modern Fergana Valley, with the Abbasid victory attributable to the defection of the Karluk Turks in the midst of the battle. However, the Arabs did not proceed any further after the battle, and the Tang retained their Central Asian territories until the An Lushan rebellion.[6][7]

Further, southern expansion of the Tang was limited by the ineffective, and even disastrous, campaigns against the Kingdom of Nanzhao. However, the concurrent Tang campaign against the Tibetan Empire was proceeding more successfully, with the campaign to capture the Tibetans' Central Asian territories appearing nearly successful. With the assassination of the Tibetan emperor Me Agtsom in 755 in the midst of a major rebellion within the Tibetan polity, final Tang victory over the Tibetan Empire seemed all but assured. However, back in the increasingly financially challenged Chinese heartland, the Sogdian-Turkic General An Lushan had worked himself into a position of trust with the Tang emperor Xuanzong and his consort Yang Guifei.

General An Lushan

An Lushan was a general of uncertain birth origins, but thought to have been adopted by a Sogdian father and Göktürk mother of the Ashina tribe.[8] Eventually he managed to become a favorite of the reigning emperor of China. His success in this regard is shown, for example, by the luxurious house Emperor Xuanzong built for him in 751, in the capital Chang'an. The house was furnished with luxuries such as gold and silver objects and a pair of ten-foot-long (3.0 m) by six-foot-wide (1.8 m) couches appliqued with rare and expensive sandalwood.[9]

He was appointed by Emperor Xuanzong (following the suggestion of Xuanzong's favorite concubine Yang Guifei and with the agreement of Chancellor Li Linfu) to be Jiedushi of three garrisons in the north—Pinglu, Fanyang and Hedong. In effect, An was given control over the entire area north of the lower reaches of the Yellow River, including garrisons about 164,000 strong. He took advantage of various circumstances, such as popular discontent with an extravagant Tang court, the synchronous Sogdian-involved Abbasid Revolution against the Umayyad dynasty,[10] and eventually the absence of strong troops guarding the palace coupled with a string of natural disasters. An Lushan was very influential in the Tang court, his close relationship with Emperor Xuanzong led to him being adopted by the imperial concubine Yang Guifei. The positions of power of Yang clan members (the family of the preceding Sui dynasty into which the Tang emperor had married) were important in this situation, especially complicated by the position of Yang Guifei's relative Yang Guozhong in the Tang governmental administration.[11]

Course of the rebellion

The An Lushan rebellion signaled a period of disorder spanning the reigns of three Tang dynasty emperors, beginning during the final (Tianbao era) period of the reign of Xuanzong (8 September 712 to 12 August 756), continuing through the reign of Suzong (12 August 756 to 16 May 762) and ending during the reign of Daizong (18 May 762 to 23 May 779), as well as spanning the four imperial claimants of the failed Yan dynasty.

Revolt and capture of Luoyang

At the end of 755 An Lushan revolted.[12] On 16 December, his army surged down from Fanyang (near modern Beijing). Along the way, An Lushan treated surrendered local Tang officials with respect. As a result, more and more of them joined his ranks. He moved rapidly along the Grand Canal and captured the "Eastern Capital" city of Luoyang on 18 January 756,[13][14] defeating the poorly supplied General Feng Changqing. There, on 5 February,^ An Lushan declared himself Emperor of the new Great Yan dynasty (大燕皇帝). His next steps would be to capture the Tang western capital of Chang'an and then to attempt to continue into southern China to complete his conquest.

Battle of Yongqiu

However, the Battle of Yongqiu, in the spring of 756, went badly for An Lushan. Although his army, under Linghu Chao, was numerous, it was unable to make further territorial gains due to the failure to wrest control of Yongqiu (modern Qi County, Kaifeng, in Henan) and (later) the nearby Suiyang from the Tang defenders led by Zhang Xun. This prevented the Yan forces from conquering southern China, before the Tang were able to recover. The Yan army did not take control of Suiyang until after the Siege of Suiyang (January–October 757), almost two years after their initial capture of Luoyang.

Advance on Chang'an

Originally, An Lushan's forces were blocked from the main imperial (or "Western") capital at Chang'an (modern Xi'an), by loyal troops placed in nearly impregnable defensive positions in the intervening high mountain passes of Tongguan. Unfortunately for Chang'an, the two generals in charge of the troops at Tong Pass, Gao Xianzhi and Feng Changqing, were executed due to a court intrigue involving the powerful eunuch Bian Lingcheng. Yang Guozhong, with grossly inept military judgment, then ordered the replacement General Geshu Han, who was in charge of the troops in the passes, together with reinforcement troops, to attack An's army on open ground. On 7 July,[15] the Tang forces were defeated. The road to the capital now lay open.

Flight of the emperor

With rebel forces clearly an imminent threat to the imperial seat of Chang'an, and with conflicting advice from his advisers, Tang emperor Xuanzong determined to flee to the relative sanctuary of Sichuan with its natural protection of mountain ranges so the Tang forces could reorganize and regroup. He brought along the bulk of his court and household. The route of travel from Chang'an to Sichuan was notoriously difficult, requiring hard travel on the way through the intervening Qin Mountains.

However, the geographical features of the terrain were not the only hardships on the journey: there was a matter that first had to be settled, involving the relationship between Xuanzong and the Yang family, especially the emperor's beloved Yang Guifei. So, before progressing more than a few kilometers along the way, an incident occurred at Mawei Inn, in today's Xingping in Xianyang, Shaanxi. Xuanzong's bodyguard troops were hungry and tired, and very angry with Yang Guozhong for exposing the whole country to danger. They demanded the death of the much-hated Yang Guozhong, and then of his cousin and imperial favorite, Yang Guifei. Soon the angry soldiers killed Yang Guozhong, Yang Xuan (his son), Lady Han and Lady Qin (Yang Guifei's sisters). With the army on the verge of mutiny, the Emperor had no choice but to agree, ordering the strangling of Lady Yang. The incident made Xuanzong fear for his own safety, so he fled to Chengdu at once. However, people stopped his horse, not wanting him to go away. So he made the crown prince, Li Heng, stay to hold the fort.[16] Instead, Li Heng fled in the other direction to Lingzhou (today called Lingwu, in Ningxia province). Later, on 12 August,[17] after reaching Sichuan, Xuanzong abdicated (becoming Taishang Huang), in favor of the crown prince, who had already been proclaimed emperor.

Fall of Chang'an

In July 756 An Lushan and his rebel forces captured Chang'an, an event that had a devastating effect upon this thriving metropolis. Before the revolt, estimates put the population within the city walls at from 800,000 to 1,000,000. Including small cities in the vicinity forming the metropolitan area, the census in 742 recorded 362,921 families with 1,960,188 persons. Much of the population fled at the approach of the rebels. Then the city was captured and looted by the rebel forces and the remaining population put in jeopardy.

A new Tang emperor

The third son of Xuanzong, Li Heng, was proclaimed Emperor Suzong at Lingzhou (modern-day Lingwu), although another group of local officials and Confucian literati tried to promote a different prince, Li Lin, the Prince of Yong, at Jinling (modern-day Nanjing). One of Suzong's first acts as emperor was to appoint the generals Guo Ziyi and Li Guangbi to deal with the rebellion. The generals, after much discussion, decided to borrow troops from an offshoot of the Turkic Tujue tribe, the Huihe, or Huige, also known as the Uyghur Khaganate, who were ruled by Bayanchur Khan until his death in the summer of 759. Three thousand Arab mercenaries were sent by the Abbasid caliph al-Mansur to join the Tang in 756 against An Lushan.[18] With Uyghur assistance, the Tang Imperial forces recaptured both Chang'an and Luoyang in late 757.[10] However, they failed to capture or subdue the rebel troops, who fled to the rebel heartland in the northeast.

Uyghur Khaganate diplomats clashed against Arab Abbasid diplomats over who would enter the diplomatic hall in Chang'an first in 758.[19][20]

Role of Nestorian Christians and Esoteric Buddhists against An Lushan

The Nestorian Church of the East Christians like the Bactrian Priest Yisi of Balkh helped the Tang dynasty general Guo Ziyi militarily crush the An Lushan rebellion, with Yisi personally acting as a military commander and Yisi and the Nestorian Church of the East were rewarded by the Tang dynasty with titles and positions as described in the Nestorian Stele.[21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30]

Epitaphs were found dating from the Tang dynasty of a Christian couple in Luoyang of a Nestorian Christian Sogdian woman, Lady An (安氏) who died in 821 and her Nestorian Christian Han Chinese husband, Hua Xian (花献) who died in 827. These Han Chinese Christian men may have married Sogdian Christian women because of a lack of Han Chinese women belonging to the Christian religion, limiting their choice of spouses among the same ethnicity.[31] Another epitaph in Luoyang of a Nestorian Christian Sogdian woman also surnamed An was discovered and she was put in her tomb by her military officer son on 22 January, 815. This Sogdian woman's husband was surnamed He (和) and he was a Han Chinese man and the family was indicated to be multiethnic on the epitaph pillar.[32] In Luoyang, the mixed raced sons of Nestorian Christian Sogdian women and Han Chinese men had many career paths available for them. Neither their mixed ethnicity nor their faith were barriers and they were able to become civil officials, military officers, and to openly celebrate their Christian religion and support Christian monasteries.[33]

Vajrayana Buddhist master Amoghavajra assisted the Tang dynasty state against the An Lushan rebellion. He carried out Vajrayana rituals which were ostensibly effective in supernaturally attacking and destroying An Lushan's army including the death of one of An Lushan's generals, Zhou Zhiguang.[34][35]

Amoghavajra used his rituals against An Lushan while staying in Chang'an when it was occupied in 756 while the Tang dynasty crown prince and Xuanzong emperor had retreated to Sichuan. Amoghavajra's rituals were explicitly intended to introduce death, disaster and disease against An Lushan.[36] As a result of Amoghavajrya's assistance in crushing An Lushan, Estoteric Buddhism became the official state Buddhist sect supported by the Tang dynasty, "Imperial Buddhism" with state funding and backing for writing scriptures, and constructing monasteries and temples. The disciples of Amoghavajra did ceremonies for the state and emperor.[37] Tang dynasty Emperor Suzong was crowned as cakravartin by Amoghavajra after victory against An Lushan in 759 and he had invoked the Acala vidyaraja against An Lushan. The Tang dynasty crown prince Li Heng (later Suzong) also received important strategic military information from Chang'an when it was occupied by An Lushan though secret message sent by Amoghavajra.[38]

Siege of Suiyang

In the beginning of 757 and continuing through October of that year, a protracted stalemate between the Yan and Tang forces occurred in Suiyang. This effectively blocked the Yan forces from attacking the extensive areas south of the Yangzi River, which remained relatively untouched by the An–Shi disturbances.

Death of An Lushan, An Qingxu became Emperor of Yan

The Tang imperial forces were helped by the newly formed dynasty's internal fighting. On 29 January 757, An Lushan was betrayed and killed by his son, An Qingxu, (An Lushan's violent paranoia posed too much of a threat to his entourage). The rebel An Lushan had a Khitan eunuch named Li Zhu'er (李豬兒) (Li Chu-erh) who was working for An Lushan when he was a teenager but An Lushan used a sword to sever his genitals and he almost died after losing multiple pints of blood. An Lushan revived him after smearing ashes on his injury. Li Zhu'er was An Lushan's eunuch after this and highly used and trusted by him. Li Zhu'er and another two men helped carry the obese An Lushan when he was taking off or putting on his clothes. Li Zhu'er helped clothe and unclothe at the Huaqing (Hua-ch'ing) steam baths granted by Emperor Xuanzang. Li Zhuer was approached by people who wanted to assassinate An Lushan after An Lushan became paranoid and blind, stricken with skin disease and started flogging and murdering his subordinates. An Lushan was hacked to death in his stomach and abdomen by Li Zhuer and another conspirator, Yan Zhuang (Yen Chuang) (嚴莊) who was beaten by An before. An Lushan screamed "this is a thief of my own household" as he desperately shook his curtains since he could not find his sword to defend himself. An Lushan's intestines came out of his body as he was hacked to death by Li Zhuer and Yan Zhuang.[39][40] A horse was once crushed to death under An Lushan's sheer weight due to his fatness.[41]

It was said that An Qingxu was an introvert who couldn't speak to others properly. As a result, Yan Zhuang advised him not to meet officials frequently, and he entrusted most of affairs of state to Yan and created Yan the Prince of Fengyi. He tried to ingratiate his generals by promoting their positions. Meanwhile, with the major general Shi Siming besieging the Tang general Li Guangbi at Taiyuan, An Qingxu ordered Shi to return to his base of Fanyang and leave the general Cai Xide (蔡希德) at Taiyuan to watch Li Guangbi's actions. He also sent the general Yin Ziqi (尹子奇) to attack the city of Suiyang, then under the defense by the Tang generals Zhang Xun and Xu Yuan (許遠), intending to capture Suiyang first and then send Yin south to capture Tang territory south of the Huai River (Yin, however, was locked into a siege of Suiyang that would last until winter 757, stopping any possibility of Yan's advancing south). To show favor to Shi, he created Shi the Prince of Guichuan and made him the jiedushi of Fanyang Circuit; instead, Shi, hoarding the supplies that An Lushan had previously shipped to Fanyang, began to disobey An Qingxu's orders, and An Qingxu could not keep him in check. When the Tang general Guo Ziyi attacked Tong Pass, intending to recapture Chang'an, however, An was able to send forces to repel Guo's attack.

Siege of Yecheng

However, the Tang prince Li Chu the Prince of Guangping (the son of Li Heng, who by this point had taken imperial title as Emperor Suzong), with aid from Huige, was able to recapture Chang'an in summer 757. Tang forces under Li Chu and Huige forces then advanced east, toward Luoyang. In winter 757, An put together his forces and sent them, under Yan Zhuang's command, to defend Shan Commandery (陝郡, roughly modern Sanmenxia, Henan). When Yan forces engaged Tang forces, however, they saw that Huige forces were on Tang's side, and, in fear, they collapsed. Yan Zhuang and Zhang Tongru (張通儒) fled back to Luoyang to inform An, and An, after executing some 30 Tang generals who had been captured, abandoned Luoyang and fled north, to Yecheng, which he converted to Ancheng Municipality.

At the time that An arrived at Yecheng, he had only 1,000 infantry soldiers and 300 cavalry soldiers. Soon, however, Yan generals Ashina Chengqing (阿史那承慶), Cai Xide, Tian Chengsi, and Wu Lingxun (武令珣), who had been attacking other Tang cities, headed to Yecheng and coalesced there, allowing An to have over 60,000 soldiers under his disposal and thus regaining some measure of strength. Meanwhile, apprehensive of Shi, he sent Ashina and An Shouzhong (安守忠) to Fanyang to order Shi to contribute troops, but was intending to have Ashina and An Shouzhong take over Shi's command if possible. Instead, Shi arrested Ashina and An Shouzhong and submitted to Tang. Many other cities previously under Yan's control also submitted to Tang, and An Qingxu's territory shrank to just Yecheng and the surrounding area. It was said that An Qingxu became cruel and paranoid in light of these military losses, and that if generals submitted to Tang, he would slaughter their families if they were Han and their tribes if they were non-Han. Meanwhile, believing accusations that Zhang made against Cai, he killed Cai, which further led to dissension among his soldiers, particularly since he then put Cui Qianyou (崔乾祐) in command of his army, and the soldiers resented Cui for his harshness.

By winter 758, the Tang generals Guo Ziyi, Lu Jiong (魯炅), Li Huan (李奐), Xu Shuji (許叔冀), Li Siye, Ji Guangchen (季廣琛), Cui Guangyuan (崔光遠), Dong Qin (董秦), Li Guangbi, and Wang Sili (王思禮), were gathering at Yecheng and putting it under siege. An Qingxu tried to fight out of the siege, but was defeated by Tang forces, and his brother An Qinghe (安慶和) was killed. Meanwhile, with Shi recently having again rebelled against Tang, An sent the general Xue Song to Fanyang to seek aid from Shi, offering the throne to him. Shi thus advanced south toward Yecheng. Meanwhile, Tang forces, under the command of nine generals (with Li Siye having died during the siege), were uncoordinated. On 7 April 759,[42] Shi engaged Tang forces—and, when a storm suddenly arrived, both armies panicked; Shi's forces fled north, and Tang forces fled south, lifting the siege on Yecheng. An Qingxu's forces gathered the food and supplies abandoned by Tang forces, and An thereafter considered, with Sun Xiaozhe (孫孝哲) and Cui, the possibility of refusing Shi, who gathered his troops and again approached Yecheng, admittance. Shi himself was not communicating with An, but was feasting his soldiers and watching Yecheng. Zhang and Gao Shang (高尚) requested permission to meet Shi, and An agreed; Shi gave them gifts and let them return to Yecheng. An, unsure what to do, again offered the throne to Shi, which Shi declined. Shi instead suggested to him that perhaps they could both be emperors of independent, allied states. An, pleased, exited Yecheng and met with Shi to swear to the alliance.

Resurgence under Shi Siming

On 10 April 759, An Qingxu was killed by Shi Siming who enthroned as Emperor Zhaowu of Yan. Shi Siming soon left Empress Xin's son Shi Chaoqing (史朝清) in charge of Fanyang and headed south. He quickly captured Bian Prefecture (汴州, roughly modern Kaifeng, Henan) and Luoyang, but his further attempts to advance were rebuffed by Tang forces at Heyang (河陽, in modern Jiaozuo, Henan) and Shan Prefecture (陝州, roughly modern Sanmenxia, Henan), and the sides stalemated.

At this time, Shi was described as cruel and prone to kill, terrorizing his army. He favored Shi Chaoqing over Shi Chaoyi and considered creating Shi Chaoqing crown prince and killing Shi Chaoyi.[43]

In spring 761, Shi Siming began another attempt to attack Shan Prefecture, wanting to attack Chang'an. He had Shi Chaoyi serve as his forward commander, but Shi Chaoyi was repeatedly repelled by the Tang general Wei Boyu (衛伯玉). Shi Siming was angered by Shi Chaoyi's failures and considered punishing him and the generals below him. On 18 April,[44] Shi Siming ordered Shi Chaoyi to build a triangular fort with a hill as its side, to store food supplies, and ordered that it be completed in one day. Near the end of the day, Shi Chaoyi had completed it, but had not plastered the walls with mud, when Shi Siming arrived and rebuked him for not applying mud. He ordered his own servants to stay and watch the plastering. He then angrily stated, "After I capture Shan Prefecture, I will kill you, thief!" That night, Shi Chaoyi's subordinates Luo Yue (駱悅) and Cai Wenjing (蔡文景) warned him that he was in dire straits—and that if he refused to take action to depose Shi Siming, they would defect to Tang. Shi Chaoyi agreed to take action, and Luo persuaded Shi Siming's guard commander General Cao (personal name lost to history) to agree with the plot. That night, Luo led 300 soldiers and ambushed Shi Siming, binding him and then beginning a return to Luoyang with the troops. On the way back to Luoyang, Luo feared that someone might try to rescue Shi Siming, and so strangled him to death. Shi Chaoyi was enthroned as the new emperor of Yan even though he failed to get widespread support from the other Yan generals.

Implosion of Yan and end of the rebellion

By 762, Emperor Suzong had become seriously ill; and the combined forces of the Tang and their Huige allies were led by his eldest son. This son, first named Li Chu, was renamed Li Yu in 758, after being named crown prince. On 18 May 762, on the death of his father, he became Emperor Daizong of Tang.

By this time it was clear that the new Yan dynasty would not last and Yan officers and soldiers began to defect to the Tang side. Then, in the winter of 762, the eastern capital Luoyang was retaken by Tang forces for the second time. Yan Emperor Shi Chaoyi attempted to flee, but was intercepted early in 763. Shi Chaoyi chose suicide over capture, dying on 17 February 763, ending the eight-year-long rebellion.

Aftermath

The end of the rebellion was a long process of rebuilding and recovery. Due to the Imperial Court's weakened condition, other disturbances flared up. The Tibetan Empire under Trisong Detsän, taking advantage of the Tang's weakness, had reconquered much of its Central Asian territories, and proceeded to capture Chang'an on 18 November 763[45] before withdrawing back to the borders of its empire.

Lulong Circuit

Li Huaixian and fellow Yan generals Xue Song, Li Baochen, and Tian Chengsi submitted to Tang thus were allowed to keep their territory. Li Huaixian was made the military governor (jiedushi) of Lulong Circuit (盧龍, headquartered in modern Beijing) consisting of Youzhou, the core territory of the former Yan. In 768, Li Huaixian was killed by his subordinates Zhu Xicai, who then took over command of the circuit. Lulong Jiedushi remained a semi-independent fief, survived the fragmentation of Tang until being annexed by Li Cunxu's Jin state in 913.

Legacy

Death toll

「賊臣不救,孤城圍逼,父陷子死,巢傾卵覆。」

— Excerpt from Yan Zhenqing's Draft of a Requiem to My Nephew about the deaths of Yan Gaoqing (Magistrate of Changshan) and Yan Jiming

Censuses taken in the half-century before the rebellion show a gradual increase in population, with the last census undertaken before the rebellion, in 755, recording a population of 52,919,309 in 8,914,709 taxpaying households. However, a census taken in 764, the year following the end of the rebellion, recorded only 16,900,000 in 2,900,000 households. Later censuses count only households, but by 855 this figure had risen to only 4,955,151 households, little over half the number recorded in 755.[46] The difference in the census figures amounts to 36 million people, two-thirds of the population of the empire, though scholars have attributed this to factors including a breakdown in taxation and census gathering.[47]

The figure of 36 million was used in Steven Pinker's book The Better Angels of Our Nature, where it is presented as proportionally the largest atrocity in history with the loss of a sixth of the world's population at that time,[48] though Pinker stated that the figure was controversial.[49] Matthew White, from whom Pinker had taken the figure of 36 million, later revised his figure down to 13 million (based on a different calculation from the census results) in his book The Great Big Book of Horrible Things.[50] White's revised figure is repeated by cultural historians such as Johan Norberg.[51][52]

Historians such as Charles Patrick Fitzgerald argue that claims of massive depopulation are incompatible with contemporary accounts of the war, which was fought intermittently over three or four provinces.[53] They point out that the numbers recorded on the postwar registers reflect not only population loss, but also a breakdown of accuracy of the census system as well as the removal from the census figures of various classes of untaxed persons, such as those in religious orders, foreigners and merchants.[47] In addition, several of the northern provinces, with approximately a quarter of the empire's population, were no longer subject to the imperial revenue system.[54] For these reasons, census numbers for the post-rebellion Tang are considered unreliable.[55]

The An Lushan rebellion was one of several wars in northern China along with the Uprising of the Five Barbarians, Huang Chao Rebellion, the wars of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms and Jin–Song Wars which caused a mass migration of Han Chinese from northern China to southern China called 衣冠南渡(yì guān nán dù).[56][57][58][59][60][61] These mass migrations led to southern China's population growth, economic, agricultural and cultural development as it stayed peaceful unlike the north.[62][63][64][65][66][67][68]

Massacres of foreigners

A massacre of foreign Arab and Persian Muslim merchants by former Yan rebel general Tian Shengong happened during the An Lushan rebellion in the Yangzhou massacre (760),[69][70] since Tian Shengong was defecting to the Tang dynasty and wanted them to publicly recognize and acknowledge him, and the Tang court portrayed the war as between rebel Hu barbarians of the Yan against Han Chinese of the Tang dynasty, Tian Shengong slaughtered foreigners as a blood sacrifice to prove he was loyal to the Han Chinese Tang dynasty state and for them to recognize him as a regional warlord without him giving up territory, and he killed other foreign Hu barbarian ethnicities as well whose ethnic groups were not specified, not only Arabs and Persians since it was directed against all foreigners.[71][72]

The former Yan rebel general Gao Juren of Goguryeo descent ordered a mass slaughter of West Asian (Central Asian) Sogdians in Fanyang, also known as Jicheng (Beijing), in Youzhou identifying them through their big noses and lances were used to impale their children when he rebelled against the rebel Yan emperor Shi Chaoyi and defeated rival Yan dynasty forces under the Turk Ashina Chengqing,.[73][74] High nosed Sogdians were slaughtered in Youzhou in 761. Youzhou had Linzhou, another "protected" prefecture attached to it, and Sogdians lived there in great numbers.[75][76] Because Gao Juren, like Tian Shengong wanted to defect to the Tang dynasty and wanted them to publicly recognize and acknowledge him as a regional warlord and offered the slaughter of the Central Asian Hu "barbarians" as a blood sacrifice for the Tang court to acknowledge his allegiance without him giving up territory, according to the book, "History of An Lushan" (安祿山史記).[77][78] Another source says the slaughter of the Hu barbarians serving Ashina Chengqing was done by Gao Juren in Fanyang in order to deprive him of his support base, since the Tiele, Tongluo, Sogdians and Turks were all Hu and supported the Turk Ashina Chengqing against the Mohe, Xi, Khitan and Goguryeo origin soldiers led by Gao Juren. Gao Juren was later killed by Li Huaixian, who was loyal to Shi Chaoyi.[79][80]

Weakening of Tang

The rebellion of An Lushan and its aftermath greatly weakened the centralized bureaucracy of the Tang dynasty, especially in regards to its perimeters. Virtually autonomous provinces and ad hoc financial organizations arose, reducing the influence of the regular bureaucracy in Chang'an.[81] The Tang dynasty's desire for political stability in this turbulent period also resulted in the pardoning of many rebels. Indeed, some were even given their own garrisons to command. Political and economic control of large swathes of the empire became intermittent or was lost, and these areas came to be controlled by fanzhen, autonomous regional authorities headed by the jiedushi (regional military governors). In Hebei, three fanzhen became virtually independent for the remainder of the Tang dynasty. Furthermore, the Tang government also lost most of its control over the Western Regions, due to troop withdrawal to central China to attempt to crush the rebellion and deal with subsequent disturbances. Continued military and economic weakness resulted in further subsequent erosions of Tang territorial control during the ensuing years, particularly in regard to the Tibetan empires. By 790 Chinese control over the Tarim Basin area was completely lost.[82] Moreover, during the rebellion, the Tang general Gao Juren massacred all the Sogdians in Fanyang, who were identified through their noses and faces.

The political decline was paralleled by economic decline, including large Tang governmental debt to Uighur money lenders.[83] The old taxation system of Zu Yong Diao no longer functioned after the rebellion. In addition to being politically and economically detrimental to the empire, the rebellion also affected the intellectual culture of the Tang dynasty. Many intellectuals had their careers interrupted, giving them time to ponder the causes of the unrest. Some lost faith in themselves, concluding that a lack of moral seriousness in intellectual culture had been the cause of the rebellion.[84] However, a political and cultural recovery eventually did occur within Tang China several decades after the rebellion, until about 820,[85] the year of the death of Emperor Xianzong of Tang. Much of the rebuilding and recovery occurred in the Jiangnan region in the south, which had escaped the events of the rebellion relatively unscathed and remained more firmly under Tang control. However, due in part to the jiedushi system, the Tang Empire by 907 devolved into what is known as the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period.[86]

The Tang dynasty recovered its power decades after the An Lushan rebellion and was still able to launch offensive conquests and campaigns like its destruction of the Uyghur Khaganate in Mongolia in 840–847.[87] The Yenisei Kyrgyz Khaganate of the Are family bolstered his ties and alliance to the Tang dynasty Imperial family against the Uyghur Khaganate by claiming descent from the Han dynasty Han Chinese general Li Ling who had defected to the Xiongnu and married a Xiongnu princess, daughter of Qiedihou Chanyu and was sent to govern the Jiankun (Ch'ien-K'un) region which later became Yenisei. Li Ling was a grandson of Li Guang (Li Kuang) of the Longxi Li family descended from Laozi which the Tang dynasty Li Imperial family claimed descent from.[88] The Yenisei Kyrgyz and Tang dynasty launched a victorious successful war between 840–848 to destroy the Uyghur Khaganate in Mongolia and its centre at the Orkhon valley using their claimed familial ties as justification for an alliance.[89] Tang dynasty Chinese forces under General Shi Xiong wounded the Uyghur Khagan (Qaghan) Ögä, seized livestock, took 5,000-20,000 Uyghur Khaganate soldiers captive, killed 10,000 Uyghur Khaganate soldiers on 13 February 843 at the battle of Shahu (kill the barbarians) mountain in 843.[90][91][92]

It was the Huang Chao rebellion in 874–884 by the native Han rebel Huang Chao that permanently destroyed the power of the Tang dynasty since Huang Chao not only devastated the north but marched into southern China which An Lushan failed to do due to the Battle of Suiyang. Huang Chao's army in southern China committed the Guangzhou massacre against foreign Arab and Persian Muslim, Zoroastrian, Jewish and Christian merchants in 878–879 at the seaport and trading entrepot of Guangzhou,[93] and captured both Tang dynasty capitals, Luoyang and Chang'an. A medieval Chinese source claimed that Huang Chao killed 8 million people.[94] Even though Huang Chao was eventually defeated, the Tang Emperors lost all their power to regional jiedushi. Huang Chao's former lieutenant Zhu Wen, who had defected to the Tang court, turned the Tang emperors into his puppets and completed the destruction of Chang'an by dismantling Chang'an and transporting the materials east to Luoyang when he forced the court to move the capital. Zhu Wen deposed the last Tang Emperor in 907 and founded Later Liang (Five Dynasties), plunging China into the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period as regional jiedushi warlords declared their own dynasties and kingdoms.

Cultural influence

The Tang dynasty hired 3,000 mercenaries from Abbasid territories, and the Uyghur Khaganate intervened for the Tang dynasty against An Lushan.

The Uyghur Khaganate exchanged princesses in marriage with Tang dynasty China in 756 to seal the alliance against An Lushan. The Uyghur Khagan Bayanchur Khan had his daughter Uyghur Princess Pijia (毗伽公主) married to Tang dynasty Chinese Prince Li Chengcai (李承采), Prince of Dunhuang (敦煌王), son of Li Shouli, Prince of Bin, while the Tang dynasty Chinese princess Ninguo married Uyghur Khagan Bayanchur.

Sogdian merchants continued as active traders in China following the defeat of the rebellion, but many of them were compelled to hide their ethnic identity. A prominent case was An Chongzhang, Minister of War and Duke of Liang, who in 756 requested of Emperor Suzong to allow him to change his name to Li Baoyu, due to his shame in sharing the same surname with the rebel leader.[95] This change of surnames was enacted retroactively for all of his family members, so that his ancestors would also be bestowed the surname Li.[95]

The events involved in the An Lushan rebellion had an immense cultural influence both in China and beyond. Many poets of the time wrote about their lives and emotions, which were deeply impacted by war and rebellion, but few poets wrote outwardly about the rebellion. In fact, only eighteen of around one hundred poems produced between the years of 755 and 763 discussed the rebellion.[96] Although the majority of poems written at the time simply do not mention the rebellion, a few poets attempted to write openly about their experiences living during the rebellion. Some examples of this include:

- The great poet Li Bai (also known as "Li Bo" or "Li Po", who lived about 701–762) avoided the rebels, but at the cost of getting involved on the wrong side of a power struggle between the princes of the royal family. He was convicted of involvement with rebellion and sentenced to exile, although he was later reprieved. His surviving poems reflect the golden days before the An Lushan rebellion, his lengthy and deliberately protracted journey toward exile (and then return as in his poem "Departing from Baidi in the Morning", together with his hardships, wandering and disillusionment as the Tang re-consolidated control after the rebellion. He died in 762, before the final defeat of the rebel forces a year later.

- Li Bai's colleague Du Fu (712–770) had finally attained a minor appointment in the imperial bureaucracy when the rebellion broke out. He spent the winter of 756 and the summer of 757 as a captive in rebel-occupied Chang'an,[97] but later managed to escape and join with Suzong's side and thus avoid charges of treason. Living until 770, his subsequent poetry is a primary source of information about the massive upheavals of the period.

- Wang Changling (698–756?), was another Tang official and renowned poet who died in the rebellion, in about 756.[98]

- Wang Wei (approximately 699–759) was captured by the rebels in 756 and sent to Luoyang, where he was forced to serve as an official in their governmental administration, for which he was briefly imprisoned after his capture by loyalist forces.[99] Dying before the end of the rebellion, somewhere between 759 and 761, Wang Wei lived his last years in retirement at his country home in Lantian, secluded in the hills.

- Wei Yingwu (737–792) of Three Hundred Tang Poems fame is credited with writing the poem "At Chuzhou on the Western Stream", apparently written in response to the seemingly helmless ship of state of the times.[100]

Later poets, such as Bai Juyi (772–846), also wrote famous verses about the events of the period of the Anshi affairs. The tragic events were epitomized in the story of Xuanzong and Yang Guifei, and generations of Chinese and Japanese painters depicted various iconic scenes, such as Yang Guifei bathing or playing a musical instrument or the flight of the imperial court on the "hard road to Shu" (that is, the royal progress to Sichuan). These artistic themes were also a major source of inspiration in Japan, in regards to the Tale of Genji, partially inspired by the story of Yang Guifei.

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ John Curtis Perry, Bardwell L. Smith (1976). Essays on Tʻang society: the interplay of social, political and economic forces. Brill Archive. p. 41. ISBN 978-90-04-04761-7.

- ↑ Szczepanski, Kallie (2019). What Was the An Lushan Rebellion?. ThoughtCo.

- 1 2 Beckwith, 140

- ↑ Beckwith, 141

- 1 2 Beckwith, 143

- ↑ ed. Starr 2004, p. 39.

- ↑ Millward 2007, p. 36.

- ↑ Beckwith, 145, note 19

- ↑ Schafer 1985, p. 137.

- 1 2 Beckwith, 146

- ↑ Stevens, Keith. "Images on Chinese popular religion altars of the heroes involved in the suppression of the An Lushan Rebellion [AD 755–763]." Journal of the Hong Kong Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 40 (2000): 155–184.

- ↑ Beckwith, 145

- ↑ Ju-n̂eng Yao, Robert baron Des Rotours (1962). Histoire de Ngan Lou-chan. p. xxi.

- ↑ Perry, L. Smith, 41

- ↑ Graff, David. Fang Guan's Chariots: Scholarship, War, and Character Assassination in the MiddleTang (PDF). p. 1.

- ↑ 中华上下五千年. 吉林出版集团有限责任公司. 2007. p. 167. ISBN 978-7-80720-980-5.

- ↑ Graff, 1

- ↑ Needham, Joseph; Ho, Ping-Yu; Lu, Gwei-Djen; Sivin, Nathan (1980). Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 4, Spagyrical Discovery and Invention: Apparatus, Theories and Gifts (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 416. ISBN 052108573X.

- ↑ Wan, Lei (2016). The First Chinese Travel Record on the Arab World: Commercial and Diplomatic Communications during the Islamic Golden Age (PDF). Qiraat No. 7 {December 2016 – January 2017). King Faisal Center For Research and Islamic Studies. p. 42. ISBN 978-6038206218.

- ↑ Wang, Zhenping (2005). Ambassadors from the Islands of Immortals: China–Japan Relations in the Han-Tang Period (illustrated ed.). University of Hawaii Press. p. 133. ISBN 0824828712.

- ↑ Morrow, Kenneth T. (May 2019). NEGOTIATING BELONGING: THE CHURCH OF THE EAST'S CONTESTED IDENTITY IN TANG CHINA (PDF) (DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The University of Texas at Dallas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY OF IDEAS). THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT DALLAS. pp. 557, 77, 78, 95, 104.

- ↑ Johnson, Scott Fitzgerald (26 May 2017). "Silk Road Christians and the Translation of Culture in Tang China". Studies in Church History. Published online by Cambridge University Press. 53: 15–38. doi:10.1017/stc.2016.3. S2CID 164239427.

- ↑ Translation by Max Deeg, 'A Belligerent Priest: Yisi and His Political Context', in Tang and Winkler, eds, From the Oxus River, 109–10 (with typographical corrections and with slight modifications based on Eccles and Lieu, 'Stele on the Diffusion of the Luminous Religion'); text and punctuation follows Pelliot, L'Inscription nestorienne.

- ↑ Deeg, Max (Cardiff University, UK) (2013). "A BELLIGERENT PRIEST– YISI AND HIS POLITICAL CONTEXT". In Tang, Li; Winkler, Dietmar W. (eds.). From the Oxus River to the Chinese Shores: Studies on East Syriac Christianity in China and Central Asia (illustrated ed.). LIT Verlag Münster. p. 113. ISBN 9783643903297.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Deeg, Max (2007). "The Rhetoric of Antiquity. Politico-Religious Propaganda in the Nestorian Steleof Chang'an 安長". Journal for Late Antique Religion and Culture. 1: 17–30. doi:10.18573/j.2007.10291. ISSN 1754-517X.

- ↑ Chen, Huailun (6 January 2021). "Hello, I'm @ChenHuailun and I'll be continuing to tweet about Christianity in Tang China. Yesterday, I introduced the Xi'an stele and its narration of Christianity's entrance into Chang'an. Today I'll continue the story and add some of its context. ~ahc #jingjiao /1" – via Twitter.

- ↑ Godwin, R. Todd (2018). Persian Christians at the Chinese Court: The Xi'an Stele and the Early Medieval Church of the East. Library of Medieval Studies. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1786723161.

- ↑ Chin, Ken-pa (2019). "Jingjiao under the Lenses of Chinese Political Theology". Religions. 10 (10): 551. doi:10.3390/rel10100551.

- ↑ Lippiello, Tiziana (2017). "ON THE DIFFICULT PRACTICE OF THE MEAN IN ORDINARY LIFE TEACHINGS FROM THE ZHONGYONG". In Hoster, Barbara; Kuhlmann, Dirk; Wesolowski, Zbigniew (eds.). Rooted in Hope: China – Religion – Christianity Vol 1: Festschrift in Honor of Roman Malek S.V.D. on the Occasion of His 65th Birthday. Monumenta Serica Monograph Series. Routledge. ISBN 978-1351672771.

- ↑ Wu, Paul (24 December 2019). "Christmas Celebrated in Ancient China Over 1000 Years Ago?". CHINA CHRISTIAN DAILY.

- ↑ Morrow, Kenneth T. (May 2019). NEGOTIATING BELONGING: THE CHURCH OF THE EAST'S CONTESTED IDENTITY IN TANG CHINA (PDF) (DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The University of Texas at Dallas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY OF IDEAS). THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT DALLAS. pp. 109–135, viii, xv, 156, 164, 115, 116.

- ↑ Morrow, Kenneth T. (May 2019). NEGOTIATING BELONGING: THE CHURCH OF THE EAST'S CONTESTED IDENTITY IN TANG CHINA (PDF) (DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The University of Texas at Dallas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY OF IDEAS). THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT DALLAS. pp. 149–150, 155–156, viii, xv.

- ↑ Morrow, Kenneth T. (May 2019). NEGOTIATING BELONGING: THE CHURCH OF THE EAST'S CONTESTED IDENTITY IN TANG CHINA (PDF) (DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The University of Texas at Dallas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY OF IDEAS). THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT DALLAS. p. 164.

- ↑ Acri, Andrea (2016). Esoteric Buddhism in Mediaeval Maritime Asia: Networks of Masters, Texts, Icons. Vol. 27 of Nalanda-Sriwijaya series. ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute. p. 137. ISBN 978-9814695084.

- ↑ Sundberg, Jeffrey (2018). "Appreciation of Relics, Stupas, and Relic Stupas in Eighth Century Esoteric Buddhism: Taisho Tripitaka Texts and Archaeological Residues in Guhya Lanka_Part 2". The Indian International Journal of Buddhist Studies. 19: 211, 230.

- ↑ Goble, Geoffrey C. (2019). Chinese Esoteric Buddhism: Amoghavajra, the Ruling Elite, and the Emergence of a Tradition. The Sheng Yen Series in Chinese Buddhist Studies. Columbia University Press. pp. 10, 11. ISBN 978-0231550642.

- ↑ Goble, Geoffrey C. (2019). Chinese Esoteric Buddhism: Amoghavajra, the Ruling Elite, and the Emergence of a Tradition. The Sheng Yen Series in Chinese Buddhist Studies. Columbia University Press. pp. 11, 12. ISBN 978-0231550642.

- ↑ Lehnert, Martin (2007). "ANTRIC THREADS BETWEEN INDIA AND CHINA 1. TANTRIC BUDDHISM – APPROACHES AND RESERVATIONS". In Heirman, Ann; Bumbacher, Stephan Peter (eds.). The Spread of Buddhism. Vol. 16 of Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 8 Uralic & Central Asian Studies (Volume 16 of Handbuch der Orientalistik: Achte Abteilung, Central Asia) (Volume 16 of Handbuch der Orientalistik. 8, Zentralasien). Brill. p. 262. ISBN 978-9004158306.

- ↑ Liu, Xu (1960). Biography of An Lu-shan, Issue 8 [Chiu Tang shu]. University of California, Chinese Dynastic Histories translations. Vol. 8. Translated by Levy, Howard Seymour. University of California Press. pp. 42, 43.

- ↑ Chamney, Lee (Fall 2012). The An Shi Rebellion and Rejection of the Other in Tang China, 618–763 (PDF) (A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History and Classics). Edmonton, Alberta: University of Alberta. p. 41. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.978.1069.

- ↑ Holcombe, Charles (2017). A History of East Asia: From the Origins of Civilization to the Twenty-First Century (2, revised ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-1108107778.

- ↑ Volume 221 of Zizhi Tongjian recorded that the siege of Yecheng was lifted on the renshen day of the 3rd month of the 2nd year of the Qianyuan era of Tang Suzong's reign. This date corresponds to 7 Apr 759 on the Gregorian calendar.

- ↑ The sources conflict with each other as to whether Shi Chaoqing was, indeed, created crown prince. His biographies in the Old Book of Tang and the New Book of Tang indicated that he was only considering it, but the Jimen Jiluan, an account of the Anshi Rebellion written by the Tang Dynasty historian Ping Zhimei (平致美) no longer extant but often cited by others,"Archived copy". Archived from the original on 4 February 2014. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) indicated that An did create Shi Chaoqing crown prince. Compare Old Book of Tang, vol. 200, part 1, and New Book of Tang, vol. 225, part 1 Archived 2008-05-28 at the Wayback Machine, with Bo Yang Edition of the Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 53 [761], citing Jimen Jiluan. - ↑ Volume 221 of Zizhi Tongjian recorded that An was killed three days after the siege of Yecheng was lifted, which happened on the renshen day of the 3rd month of the 2nd year of the Qianyuan era of Tang Suzong's reign. This date corresponds to 7 Apr 759 on the Gregorian calendar. Thus, by calculation, An was killed on the yihai day of the same month, which corresponds to 10 Apr 759 on the Gregorian calendar.

- ↑ Beckwith 1987, p. 146

- ↑ Durand, John D. (1960). "The Population Statistics of China, A.D. 2–1953". Population Studies. 13 (3): 209–256. doi:10.1080/00324728.1960.10405043. JSTOR 2172247.

- 1 2 Schafer 1985, p. 280, note 18.

- ↑ Pinker, Steven (2011). The Better Angels of Our Nature. Penguin Books. p. 194. ISBN 978-1-846-14093-8.

- ↑ Pinker, 707

- ↑ White, Matthew (2011). The Great Big Book of Horrible Things: The Definitive Chronicle of History's 100 Worst Atrocities. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-08192-3.

- ↑ Norberg, Johan (2016). Progress: Ten Reasons to Look Forward to the Future. Oneworld Publications. p. 95. ISBN 978-1-78074-951-8.

- ↑ Gross, Alan G. (2018). "Steven Pinker and the Scientific Sublime: How a New Category of Experience Transformed Popular Science". In Rutten, Kris; Blancke, Stefaan; Soetaert, Ronald (eds.). Perspectives on Science and Culture. Purdue University Press. pp. 19–37. doi:10.2307/j.ctt2204rxr.6. ISBN 978-1-61249-522-4. JSTOR j.ctt2204rxr.6. p. 33.

- ↑ Fitzgerald, C.P. (1961). China: A Short Cultural History (3rd ed.). pp. 313–315.

- ↑ Fairbank, 86

- ↑ Durand, 224

- ↑ 衣冠南渡 .在线新华字典[引用日期2013-08-09

- ↑ 唐宋时期的北人南迁 .内蒙古教育出版社官网.2008-01-15[引用日期2013-08-09]

- ↑ 六朝时期北人南迁及蛮族的流布 .内蒙古教育出版社官网.2008-01-15[引用日期2013-08-09]

- ↑ 东晋建康的开始—永嘉南渡 .通南京网.2012-10-10[引用日期2013-08-09]

- ↑ 从衣冠南渡到西部大开发 .中国期刊网.2011-4-26 [引用日期2013-08-12]

- ↑ 中华书局编辑部.全唐诗.北京:中华书局,1999-01-1 :761

- ↑ Yao, Yifeng (2016). Nanjing: Historical Landscape and Its Planning from Geographical Perspective (illustrated ed.). Springer. p. 95. ISBN 978-9811016370.

- ↑ "Six Dynasties". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. 4 December 2008.

- ↑ Entenmann, Robert Eric (1982). Migration and settlement in Sichuan, 1644–1796 (reprint ed.). Harvard University. p. 14.

- ↑ Shi, Zhihong (2017). Agricultural Development in Qing China: A Quantitative Study, 1661–1911. The Quantitative Economic History of China. Brill. p. 154. ISBN 978-9004355248.

- ↑ Hsu, Cho-yun (2012). China: A New Cultural History. Masters of Chinese Studies (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. p. 194. ISBN 978-0231528184.

- ↑ Pletcher, Kenneth, ed. (2010). The History of China. Understanding China (illustrated ed.). The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. p. 127. ISBN 978-1615301096.

- ↑ Chinese journal of international law, Volume 3. Chinese journal of international law. 2004. p. 631.

- ↑ Wan, Lei (2017). The earliest Muslim communities in China (PDF). Qiraat No. 8 (February – March 2017). King Faisal Center For Research and Islamic Studies. p. 11. ISBN 978-603-8206-39-3.

- ↑ Qi 2010, p. 221–227.

- ↑ Chamney, Lee. The An Shi Rebellion and Rejection of the Other in Tang China, 618–763 (PDF) (A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History and Classics). University of Alberta Libraries. pp. 91, 92, 93.

- ↑ Old Tang History "至揚州,大掠百姓商人資產,郡內比屋發掘略遍,商胡波斯被殺者數千人" "商胡大食, 波斯等商旅死者數千人波斯等商旅死者數千人."

- ↑ Hansen, Valerie (2003). "New Work on the Sogdians, the Most Important Traders on the Silk Road, A.D. 500–1000". T'oung Pao. 89 (1/3): 158. doi:10.1163/156853203322691347. JSTOR 4528925.

- ↑ Hansen, Valerie (2015). "Chapter 5 – The Cosmopolitan Terminus of the Silk Road". The Silk Road: A New History (illustrated, reprint ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 157–158. ISBN 978-0190218423.

- ↑ Morrow, Kenneth T. (May 2019). NEGOTIATING BELONGING: THE CHURCH OF THE EAST'S CONTESTED IDENTITY IN TANG CHINA (PDF) (DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The University of Texas at Dallas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY OF IDEAS). THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT DALLAS. pp. 110, 111.

- ↑ de la Vaissière, Étienne (2018). Sogdian Traders: A History. Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 8 Uralic & Central Asian Studies. Brill. p. 220. ISBN 978-9047406990.

- ↑ Chamney, Lee. The An Shi Rebellion and Rejection of the Other in Tang China, 618–763 (A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History and Classics). University of Alberta Libraries. pp. 93, 94. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.978.1069.

- ↑ History of An Lushan (An Lushan Shiji 安祿山史記) "唐鞠仁今城中殺胡者重賞﹐於是羯胡盡殪﹐小兒擲於中空以戈_之。高鼻類胡而濫死者甚眾"

- ↑ "成德军的诞生:为什么说成德军继承了安史集团的主要遗产" in 时拾史事 2020-02-08

- ↑ 李碧妍, 《危机与重构:唐帝国及其地方诸侯》2015-08-01

- ↑ DeBlasi, Anthony (2001). "Striving for Completeness: Quan Deyu and the Evolution of the Tang Intellectual Mainstream". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. Harvard-Yenching Institute. 61 (1): 5–36. doi:10.2307/3558586. JSTOR 3558586.

- ↑ Beckwith, 157

- ↑ Beckwith, 158

- ↑ DeBlasi (2001) p. 7

- ↑ Schafer 1985, pp. 9–10.

- ↑ Fairbank, 86–87

- ↑ Baumer 2012, p. 310.

- ↑ Drompp, Michael Robert (2005). Tang China And The Collapse Of The Uighur Empire: A Documentary History. Vol. 13 of Brill's Inner Asian Library (illustrated ed.). BRILL. pp. 126, 291, 190, 191, 15, 16. ISBN 9004141294.

- ↑ Drompp, Michael R. (1999). "Breaking the Orkhon Tradition: Kirghiz Adherence to the Yenisei Region after A. D. 840". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 119 (3): 390–403. doi:10.2307/605932. JSTOR 605932. Retrieved 4 September 2021.

- ↑ Drompp, Michael Robert (2005). Tang China And The Collapse Of The Uighur Empire: A Documentary History. Vol. 13 of Brill's Inner Asian Library (illustrated ed.). BRILL. p. 114. ISBN 9004141294.

- ↑ Drompp, Michael R. (2018). "THE UIGHUR-CHINESE CONFLICT OF 840–848". In Cosmo, Nicola Di (ed.). Warfare in Inner Asian History (500-1800). Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 8 Uralic & Central Asian Studies. BRILL. p. 92. ISBN 978-9004391789.

- ↑ Drompp, Michael R. (2018). "THE UIGHUR-CHINESE CONFLICT OF 840–848". In Cosmo, Nicola Di (ed.). Warfare in Inner Asian History (500-1800). Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 8 Uralic & Central Asian Studies. BRILL. p. 99. ISBN 978-9004391789.

- ↑ Gernet 1996, p. 292.

- ↑ 《殘唐五代史演義傳》:"卓吾子評:'僖宗以貌取人,失之巢賊,致令殺人八百萬,血流三千里'"

- 1 2 Howard, Michael C., Transnationalism in Ancient and Medieval Societies, the Role of Cross Border Trade and Travel, McFarland & Company, 2012, p. 135.

- ↑ Lam, Eve (2001). The Royal Asiatic Society (Hong Kong Branch): the faces, the stories and the memories (Thesis). The University of Hong Kong Libraries. doi:10.5353/th_b3197246.

- ↑ Cotterell and Cotterell, 164

- ↑ Rexroth, 132

- ↑ Davis, x

- ↑ Wu, 162

Sources

- Baumer, Christoph (2012), The History of Central Asia: The Age of the Steppe Warriors

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (2009): Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13589-2.

- Bender, Lucas Rambo. "Other Poetry on the An Lushan Rebellion: Notes on Time and Transcendence in Tang Verse." Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 79.1 (2019): 1–48. Online

- Davis, A. R., Editor and Introduction (1970), The Penguin Book of Chinese Verse. (Baltimore: Penguin Books).

- Cotterell, Yong Yap and Arthur Cotterell (1975). The Early Civilization of China. New York: G.P.Putnam's Sons ISBN 0-399-11595-1

- Fairbank, John King (1992), China: A New History. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press/Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-11670-4

- ——— (1996), A History of Chinese Civilization (2nd ed.), New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-49781-7

- Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231139243. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- E. G. Pulleyblank, The Background of the Rebellion of An Lu-Shan, London: Oxford University Press (1955).

- E. G. Pulleyblank, "The An Lu-Shan Rebellion and the Origins of Chronic Militarism in Late T'ang China", in Perry & Smith, Essays on T'ang Society, Leiden: E. J. Brill (1976).

- Qi, Dongfang (2010), "Gold and Silver Wares on the Belitung Shipwreck", in Krahl, Regina; Guy, John; Wilson, J. Keith; Raby, Julian (eds.), Shipwrecked: Tang Treasures and Monsoon Winds, Washington, DC: Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, pp. 221–227, ISBN 978-1-58834-305-5, archived from the original (PDF) on 4 May 2021, retrieved 9 February 2022

- Rexroth, Kenneth (1970). Love and the Turning Year: One Hundred More Poems from the Chinese. New York: New Directions.

- Schafer, Edward H. (1985). The Golden Peaches of Samarkand. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05462-2.

- Denis Twitchett (ed.), The Cambridge History of China, Volume 3, Sui and T'ang China, Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press (1979). ISBN 978-0-521-21446-9.

- Starr, S. Frederick, ed. (2004). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland (illustrated ed.). M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 0765613182. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Wu, John C. H. (1972). The Four Seasons of Tang Poetry. Rutland, Vermont: Charles E.Tuttle. ISBN 978-0-8048-0197-3.

External links

- Tang (618–907), Chinese Graphic Arts Net

- Chinese History – Tang dynasty 唐 (618–907), Chinaknowledge.org

- "Empress of the dynasty". Daming Palace. Episode 3. China Central Television. CCTV-9 Documentary.

- The An Lushan rebellion by In Our Time (BBC Radio 4)