| Part of a series on |

| Anarchism |

|---|

|

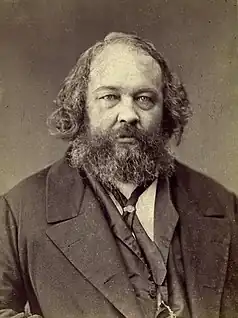

Anarchism and nationalism both emerged in Europe following the French Revolution of 1789 and have a long and durable relationship going back at least to Mikhail Bakunin and his involvement with the pan-Slavic movement prior to his conversion to anarchism. There has been a long history of anarchist involvement with nationalism all over the world as well as with internationalism.

During the early 20th century, anarchism was very supportive of anationalism and Esperanto.[1][2][3] After the Spanish Civil War, Francoist Spain persecuted anarchists and Catalan nationalists, among whom the use of Esperanto was extensive.[4]

Irish anarchist Andrew Flood argues that anarchists are not nationalists and are completely opposed to it, but rather they are anti-imperialists.[5] Similarly, the Anarchist Federation in Britain and Ireland views nationalism as an ideology totally bound up with the development of capitalism and unable to go beyond it.[6]

Overview

Anarchist opposition to nationalism

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, the first person to call himself an anarchist in a positive sense, opposed nationalism, arguing that the "end of militarism is the mission of the nineteenth century, under pain of indefinite decadence".[7] Proudhon argued that under his proposed mutualism "[t]here will no longer be nationality, no longer fatherland, in the political sense of the words: they will mean only places of birth. Man, of whatever race or colour he may be, is an inhabitant of the universe; citizenship is everywhere an acquired right".[8] Anarchism has supported both anationalism and the Esperanto language.[1][2][3]

A critique of nationalism from an anarchist point of view is Rudolf Rocker's 1937 book Nationalism and Culture. American anarchist Fredy Perlman wrote a number of pamphlets that were strongly critical of all forms of nationalism, including Anti-Semitism and the Beirut Pogrom (a critique of Zionism)[9] and The Continuing Appeal of Nationalism in which Perlman argues that nationalism is a process of state formation inspired by imperialism which capitalists, fascists and Leninists use as a mean of controlling their subjects.[10]

In 1984, Perlman also wrote a work in the post-left anarchist tradition on the subject of nationalism called The Continuing Appeal of Nationalism.[11] In it, Perlman argues that "[l]eftist or revolutionary nationalists insist that their nationalism has nothing in common with the nationalism of fascists and national socialists, that theirs is a nationalism of the oppressed, that it offers personal as well as cultural liberation".[11] To challenge these claims and in his view "to see them in a context",[11] Perlman asks "what nationalism is - not only the new revolutionary nationalism but also the old conservative one".[11] Perlman concludes that nationalism is an aid to capitalist control of nature and people regardless of its origin. Nationalism provides a form through which "[e]very oppressed population can become a nation, a photographic negative of the oppressor nation" and that "[t]here's no earthly reason for the descendants of the persecuted to remain persecuted when nationalism offers them the prospect of becoming persecutors. Near and distant relatives of victims can become a racist nation-state; they can themselves herd other people into concentration camps, push other people around at will, perpetrate genocidal war against them, procure preliminary capital by expropriating them".[11]

Mikhail Bakunin and nationalism

Prior to his involvement with the anarchist movement, Mikhail Bakunin had a long history of involvement in nationalist movements of various kinds. In his Appeal to the Slavs (1848), Bakunin called for cooperation between nationalist revolutionary movements across Europe (both Slavic and non-Slavic) to overthrow empires and dissolve imperialism in an uprising of "all oppressed nationalities" which would lead to a "Universal Federation of European Republics".[12] Bakunin also agitated for a United States of Europe, a contemporary nationalist vision originated by revolutionary Italian nationalist and fellow socialist Giuseppe Mazzini.[13]

Later exiled to eastern Siberia, Bakunin became involved with a circle of Siberian nationalists who planned to separate from the Russian Empire. They were connected with his cousin and patron Nikolay Muravyov-Amursky, the Governor General of Eastern Siberia, whom Bakunin defended in Alexander Herzen's journal The Bell.[14] It was not until a full four years after leaving Siberia that Bakunin proclaimed himself an anarchist. Max Nettlau remarked of this period in his life that "[t]his may be explained by Bakunin's increasing nationalist psychosis, induced and nourished by the expansionist ideas of the officials and exploiters who surrounded him in Siberia, causing him to overlook the plight of their victims".[15]

National-anarchism

Among the first advocates of national-anarchism were Hans Cany, Peter Töpfer and former National Front activist Troy Southgate, founder of the National Revolutionary Faction, a since disbanded British-based organization which cultivated links to certain far-left and far-right circles in the United Kingdom and in post-Soviet states, not to be confused with the national-anarchism of the Black Ram Group.[16][17][18] In the United Kingdom, national-anarchists worked with Albion Awake, Alternative Green (published by former Green Anarchist editor Richard Hunt) and Jonathan Boulter to develop the Anarchist Heretics Fair.[17] Those national-anarchists cite their influences primarily from Mikhail Bakunin, William Godwin, Peter Kropotkin, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Max Stirner and Leo Tolstoy.[16] However, the ideas that have influenced the national-anarchists could be seen as cherry-picked to fit a nationalist narrative, running contrary to the beliefs expressed by the influential anarchists.

A position developed in Europe during the 1990s, national-anarchist groups have arisen worldwide, most prominently in Australia (New Right Australia/New Zealand), Germany (International National Anarchism) and the United States (BANA).[17][18] National-anarchism has been described as a radical right-wing[19][20][21] nationalist ideology which advocates racial separatism and white racial purity.[16][17][18] National-anarchists claim to syncretize neotribal ethnic nationalism with philosophical anarchism, mainly in their support for a stateless society whilst rejecting anarchist social philosophy.[16][17][18] The main ideological innovation of national-anarchism is its anti-state palingenetic ultranationalism.[19] National-anarchists advocate homogeneous communities in place of the nation state. National-anarchists claim that those of different ethnic or racial groups would be free to develop separately in their own tribal communes while striving to be politically meritocratic, economically non-capitalist, ecologically sustainable and socially and culturally traditional.[16][18]

Although the term national-anarchism dates back as far as the 1920s, the contemporary national-anarchist movement has been put forward since the late 1990s by British political activist Troy Southgate, who positions it as being "beyond left and right".[16] The few scholars who have studied national-anarchism conclude that it represents a further evolution in the thinking of the radical right rather than an entirely new dimension on the political spectrum.[19][20][21] National-anarchism is considered by anarchists as being a rebranding of totalitarian fascism and an oxymoron due to the inherent contradiction of anarchist philosophy of anti-fascism, abolition of hierarchy, dismantling of national borders and universal equality between different nationalities as being incompatible with the idea of a synthesis between anarchism and fascism.[18]

National-anarchism has elicited skepticism and outright hostility from both left-wing and far-right critics.[17][18] Critics, including scholars, accuse national-anarchists of being nothing more than white nationalists who promote a communitarian and racialist form of ethnic and racial separatism while wanting the militant chic of calling themselves anarchists without the historical and philosophical baggage that accompanies such a claim, including the anti-racist egalitarian anarchist philosophy and the contributions of Jewish anarchists.[17][18] Some scholars are skeptical that implementing national-anarchism would result in an expansion of freedom and describe it as an authoritarian anti-statism that would result in authoritarianism and oppression, only on a smaller scale.[22]

By country

China

Anarchists formed the first labor unions and the first large-scale peasant organizations in China. During the roughly two decades when anarchism was the dominant radical ideology in China (roughly 1900–1924), anarchists there were active in mass movements of all kinds, including the nationalist movement.

A small group of anarchists, mostly those associated with the early Paris Group, a grouping of Chinese expatriates based in France, were deeply involved in the nationalist movement and many served as "movement elders" in the Kuomintang (KMT) right up until the defeat of the Nationalists by the Maoists. A minority of Chinese anarchists associated with the Paris Group also helped funnel large sums of money to Sun Yat-sen to help finance the Nationalist Revolution of 1911.

After the Nationalist Revolution, anarchist involvement with the Kuomintang was relatively minor, not only because the majority of anarchists opposed nationalism on principle, but also because the KMT government was more than willing to level repression against anarchist organizations whenever and wherever they challenged state power. Still, a few prominent anarchists, notably Jing Meijiu and Zhang Ji, both affiliated with the Tokyo Group, were elected to positions within the KMT government and continued to call themselves anarchists while doing so. The response from the larger anarchist movement was decidedly mixed. They were roundly denounced by the Guangzhou group, but other groupings that favored an evolutionary approach to social change instead of immediate revolution such as the Pure Socialists were more sympathetic.

The "Diligent Work and Frugal Study" program in France, a series of businesses and educational programs organized along anarchist lines that allowed Chinese students from working-class backgrounds to come to France and receive a European education that had previously been only available to a tiny wealthy elite, was one product of this collaboration of the anarchists with nationalists. The program received funding from both the Chinese and French governments as well as raising its own independent funds through a series of worker-owned anarchist businesses, including a tofu factory that catered to the needs of Chinese migrant workers in France. The program allowed poor and working-class Chinese students to receive a high-quality modern university education in France at a time when foreign education was almost exclusively limited to the children of wealthy elites, and educated thousands of Chinese workers and students, including many future Chinese Communist Party (CPC) leaders such as Deng Xiaoping.

Following the success of the Bolsheviks in the Russian Revolution, anarchism went into decline in the Chinese labour movement. In 1924, the CPC allied itself with the nationalist KMT. Originally composed of many former anarchists, it soon attracted a mass base, becoming increasingly critical of anarchism. When the Kuomintang purged the CPC from its ranks in 1927, the small group of anarchists who had long participated in the KMT urged their younger comrades to join the movement and utilize it in the same way that the Stalinists had been using it as a vehicle to gain membership and influence.

Partly because of the growing power of the right-wing within the KMT and the repression of workers movements advocated by that right-wing, the anarchists opted not to join the KMT en masse or even work within it. Instead, the result of this last collaboration was the creation of China's first Labor University. The Labor University was intended to be a domestic version of the Paris groups Diligent Work and Frugal Study educational program and sought to create a new generation of labor intellectuals who would finally overcome the gap between "those who work with their hands" and "those who work with their minds". The goal was to train working-class people with the skills they needed to self-organize and set up their own independent organizations and worker-owned businesses which would form the seed of a new anarchist society within the shell of the old in a dual power-based evolutionary strategy reminiscent of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon.

The university would only function for a very few years before the Nationalist government decided that the project was too subversive to allow it too continue and pulled funding. When the KMT initiated a second wave of political repression against the few remaining mass movements, anarchists left the organization en masse and were forced underground as hostilities between the KMT and the CPC, both of whom were hostile towards the anarchists, who are anti-authoritarians and libertarians, escalated.

Ireland

The armed struggle against British rule in Ireland, particularly up to and during the Irish War of Independence, is portrayed as a national liberation struggle within the Celtic anarchist milieu. Anarchists, including the platformist Workers Solidarity Movement (WSM), support a complete end to British involvement in Ireland, a stance traditionally associated with Irish republicanism, but they are also very critical of statist nationalism and the Irish Republican Army (IRA) in particular. Anarchists are extremely critical of the IRA as well as of the various loyalist paramilitaries because of their use of political violence and internal authoritarianism. From the anarchist view, British and Irish nationalism are both authoritarian, statist and seek to dominate and exploit the Irish nation to empower their competing sovereign states. Anarchism would instead create a political system without the nation state where communities are self-governing on the local level. The achievement of home rule, or political self-determination, is therefore a precondition for and a consequence of anarchism. At its root, the anarchist objection to Irish nationalism is that nationalists use reprehensible means to demand far too little. Still, anarchists seek to learn from and examine the liberatory aspects of the struggle for Irish independence and the WSM includes a demand for complete British withdrawal from Northern Ireland in its platform.

In two articles published on Anarkismo.net, Andrew Flood of the WSM outlines what he argues was the betrayal of class struggle by the IRA during the war of independence and argues that the statism of traditional Irish nationalism forced it to place the interests of wealthy Irish nationalists who were financing the revolution ahead of the interests of the vast majority of Ireland's poor. The Irish Citizens Army, a workers militia which was led by James Connolly and based in the radical wing of the Irish Home Rule and Irish union movements, is held up as a better example of how the larger revolutionary movement could have and should have been organized.[23]

The WSM has produced a number of articles and essays on the relationship between anarchism and Irish republicanism over the years. Their position is that anarchism and republicanism are incompatible and opposed to each other, but that anarchists can and should learn things from Ireland's long history of struggle. In their analysis, republicanism has always been split between rich people who want to rule directly and working class movements that demand social equality and community self-governance instead of simply trading foreign bosses for local ones. In "The Republican Tradition – A Place to Build From?", the WSM wrote:

In Ireland in the 1790s we had a mass republican movement influenced by the American and then the French revolutions. That movement included those who favored a radical leveling agenda as well as the democratic agenda of mainstream republicans. Edward Fitzgerald, the military planner of the rising was one such proponent. But it also contained those like Wolfe Tone who saw an independent Ireland as opening up its own colonies in the Caribbean. In the north Henry Joy McDonald had to remove the existing United Irish leadership paralyzed by fear of the mob seizing property before the rising there could get underway, weeks after it had begun in the south. After its defeat and before his execution he warned future republicans to beware that "the rich always betray the poor." [...] This process was mirrored in republican movements elsewhere. Left republicans would build real popular struggle but then be confronted with the need to preserve national unity in the face of the wealthy republicans whose funds were often needed for arms backing off because they feared for their privilege. And this is where we find the roots of the early anarchist movement. [...] So in terms of historical development anarchism and republicanism have a lot in common, in fact anarchism is arguably an offshoot of republicanism, an offshoot that emerged for the first time in the 1860s but has emerged on other occasions since then including in 1970s Ireland where some of those leaving the official republican movement became anarchists while other anarchists were joining both provisional and official republican movements.[24]

According to this analysis, anarchism is the successor to left-wing nationalism, a working-class movement working to achieve the liberation that the republican movements that toppled the worlds monarchies in the last two centuries promised, albeit never delivered. According to the WSM, although the ideas of anarchism are fundamentally different from those of nationalism, it is still possible to learn from nationalist movements by studying the working-class elements of those movements that demanded more than the bourgeoisie leadership was willing or able to deliver. In "An Anarchist Perspective on Irish Nationalism", Irish anarchist Andrew Flood wrote:

Anarchists are not nationalists, in fact we are completely against nationalism. We don't worry about where your granny was born, whether you can speak Irish or if you drink a green milkshake in McDonalds on St Patrick's Day. But this doesn't mean we can ignore nations. They do exist; and some nationalities are picked on, discriminated against because of their nationality. Irish history bears a lot of witness to this. The Kurds, Native Americans, Chechins, and many more have suffered also – and to an amazingly barbaric degree. National oppression is wrong. It divides working class people, causes terrible suffering and strengthens the hand of the ruling class. Our opposition to this makes us anti-imperialists. [...] So fight national oppression but look beyond nationalism. We can do a lot better. Changing the world for the better will be a hard struggle so we should make sure that we look for the best possible society to live in. We look forward to a world without borders, where the great majority of people have as much right to freely move about as the idle rich do today. A worldwide federation of free peoples – classless and stateless – where we produce to satisfy needs and all have control over our destinies – that's a goal worth struggling for.[5]

The Anarchist Federation views nationalism as an ideology totally bound up with the development of capitalism and unable to go beyond it, stating:

At heart, nationalism is an ideology of class collaboration. It functions to create an imagined community of shared interests and in doing so to hide the real, material interests of the classes which comprise the population. The 'national interest' is a weapon against the working class, and an attempt to rally the ruled behind the interests of their rulers. [...] Anarchist communists do not simply oppose nationalism because it is bound up in racism and parochial bigotry. It undoubtedly fosters these things, and has mobilised them through history. Organising against them is a key part of anarchist politics. But nationalism does not require them to function. Nationalism can be liberal, cosmopolitan and tolerant, defining the 'common interest' of 'the people' in ways which do not require a single 'race'. Even the most extreme nationalist ideologies, such as fascism, can co-exist with the acceptance of a multiracial society, as was the case with the Brazilian Integralist movement. Nationalism uses what works – it utilises whatever superficial attribute is effective to bind society together behind it.[6]

India

In the 1910s, Lala Har Dayal became an anarchist agitator in San Francisco, joining the Industrial Workers of the World before becoming a pivotal figure in the Ghadar Party. A long-time advocate of Indian nationalism, Dayal developed a vision of anarchism based upon a return to the principles of ancient Aryan society.[25] Dayal was particularly influenced by Guy Aldred, who was jailed for printing The Indian Sociologist in 1907. An anarcho-communist, Aldred was careful to point out that this solidarity arose because he was an advocate of free speech and not because he felt that nationalism would help the working class in British India or elsewhere.[26]

Spain

During the Spanish Civil War, Spanish anarchists and Basque nationalists fought together against the Francoist Nationalist side. The anarchist Felix Likiniano fought fascism even from the French Resistance. Along with Federico Krutwig, Likiniano tried to synthesize Basque nationalism and anarchism. In France, Likiniano befriended disgruntled members of the Euzko Gaztedi and created for them the symbol of the axe and the snake and the Bietan jarrai motto that they adopted for their new revolutionary armed organization ETA.[27]

Ukraine

Classical anarchist theory posed anti-statism as a solution to the national question, claiming that without a state "the bourgeoisie is no longer able to oppress the workers by playing on their nationalism" and that abolishing the state would naturally put an end to the oppression of one nation by another.[28] Most classical anarchists in the Russian Empire therefore dismissed nationalism entirely, although a minority still paid attention to the national question, with Maksim Rayevsky and Peter Kropotkin expressing their support for the national liberation of Poles, Georgians and Jews, among other minority nationalities.[29] With the outbreak of the 1905 Russian Revolution, anarchist activity in Ukraine was mostly limited to Russified urban centers, with the anarchist movement largely taking on a Russian character, both linguistically and culturally. Although Ukrainian Jews were themselves a notably large force within the anarchist movement, ethnic Ukrainian participation in the anarchist movement was rather limited, with no evidence of anarchist periodicals being published in the Ukrainian language during this period.[30] Of the locations that were noted for sustained anarchist activity, only a quarter of them displayed a national consciousness, all of which were small towns in Northern Ukraine.[31]

Following the ratification of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, the Ukrainian peasantry began to revolt against the conservative Hetmanate and the occupying forces of the Central Powers. The Directorate of Ukraine assumed leadership of the rebellion in the north-west, while Nestor Makhno prosecuted a guerrilla war in the southern steppe.[32] Despite attempts to form an alliance between the two forces, Makhno ardently rejected cooperation with the "counterrevolutionaries" that sought to establish a Ukrainian nation state.[33] Throughout the Ukrainian War of Independence, the Ukrainian anarchists took a stance of internationalism and condemned Ukrainian nationalism in their Russian language newspapers.[34] When the Ukrainian nationalist Nykyfor Hryhoriv launched an anti-Bolshevik uprising, the Makhnovists immediately condemned him for his antisemitism and his divisive politics. According to the historian Frank Sysyn, "the [anarchist] movement as a whole [was] opposed to Ukrainian nationalism."[35] There was only one short-lived case of cooperation between the Ukrainian nationalists and the anarchists, in September 1919, when the Ukrainian Sich Riflemen accepted a wounded Makhnovist contingent that had been forced into retreat by Denikin's offensive.[36] Only four days later, the Makhnovists denounced Petliura as an agent of the White movement and the Petliurists began to fear Makhno intended to "deal with Petliura as he had with Hryhoriv."[37]

Despite their hostility to Ukrainian nationalism, the Ukrainian anarchists were not "anti-Ukrainian", as they recognized the Ukrainian nation and culture.[38] In October 1919, when the use of the Ukrainian language in schools was forbidden in South Russia, the Makhnovshchina's "Cultural Enlightenment Section" declared that people were to be educated in whichever language was used by the local population, to be decided on voluntarily by the people themselves.[39] It was this that finally brought the Makhnovists to establish a newspaper in the Ukrainian language, dealing with issues specific to Ukraine.[40] Driven by a small number of Ukrainian intellectuals, led by Halyna Kouzmenko, the Makhnovschina increasingly used the Ukrainian language in both its propaganda and educational activities, leading to a notable Ukrainization of the Makhnovist movement.[41] Kouzmenko even attempted to convert the Makhnovists to Ukrainian nationalism, but this campaign was aborted after a nationalist plot to assassinate Makhno was uncovered. Nevertheless, Ukrainian cultural activities and the Ukrainization of the Makhnovschina continued unabated.[42] Despite the movement's increased Ukrainization, the bulk of the movement's cadre was still made up of Russian and Jewish anarchists, who espoused a clear internationalist and anti-nationalist ideology.[43]

The Soviet historian Mikhail Kubanin noted that the number of ideological anarchists within the Makhnovist ranks diminished substantially by the later period of the war, with the Nabat themselves breaking with the Makhnovists by November 1920. But his claims of the Makhnovists forming a "truce, non-aggression pact, and joint action against the Soviets" with the Petliurists were contradicted by his own sources, which noted "no official link" between the two opposing camps and only scant examples of "certain chance meetings".[44] There were cases of former Petliurists joining the Makhnovists in 1920, which introduced more Ukrainian nationalists into their ranks, but Makhno claimed to resist their influence, as the Makhnovist command was still strongly opposed to nationalism.[45] Former Makhnovists came to view the confluence of Ukrainian nationalists and the anarchists as a result of desperation, brought on only at the last minute by the successful Russian offensive, rather than as the culmination of a gradually increasing nationalist sentiment.[46]

While the emergence of a Ukrainian national consciousness had largely been a product of the war of independence against the Hetmanate, the Ukrainian anarchist movement only developed a national consciousness as a result of the Bolshevik victory in the Soviet–Ukrainian War, having paid little attention to the national question during the course of the war.[47] While exiled in Paris, Nestor Makhno himself began to develop an anarchist theory of Ukrainian national liberation in reaction to the Soviet policy of Korenizatsiya. Himself a Russified Ukrainian, involved deeply in the Russian anarchist movement, Makhno had been disinterested in the Ukrainian national revival during the conflict due to his acceptance of the anarchist position on anti-nationalism. But following the rise in Ukrainian nationalism during the 1920s, the national question began to be taken up by broader sections of the Ukrainian political sphere, even by anarchists, with Makhno devoting much thought to it in his memoirs and in the pages of Dielo Truda.[48]

Anarchism and anti-imperialism

Black anarchism

Black anarchism opposes the existence of a state and subjugation and domination of people of color, favoring a non-hierarchical organization of society. Black anarchists seek to abolish the state alongside capitalism and white supremacy. Theorists include Ashanti Alston, Lorenzo Kom'boa Ervin, Kuwasi Balagoon, many former members of the Black Panther Party and Martin Sostre. Black anarchism rejects the classical anarchist movement on racial issues.

Black anarchists oppose the anti-racist conception, based on the universalism of the Age of Enlightenment which is proposed by the classical anarchist tradition, arguing that it is not adequate enough to struggle against racism and that it disguises real inequalities by proclaiming a de jure equality. Pedro Ribeiro has criticized the whole of the anarchist movement by declaring that "[i]t is a white, petty-bourgeois Anarchism that cannot relate to the people. As a Black person, I am not interested in your Anarchism. I am not interested in individualistic, self-serving, selfish liberation for you and your white friends. What I care about is the liberation of my people".[49]

Black anarchists are influenced by the civil rights movement and the Black Panther Party, seeking to forge their own movement that represents their own identity and tailored to their own unique situation. However, in contrast to black activism that was in the past based in leadership from hierarchical organizations, black anarchism rejects such methodology in favor of developing organically through communication and cooperation to bring about an economic and cultural revolution that does away with capitalism, racist domination and the state. In the @narchist Panther Zine, Alston wrote:

Panther anarchism is ready, willing and able to challenge old nationalist and revolutionary notions that have been accepted as 'common-sense.' It also challenges the bullshit in our lives and in the so-called movement that holds us back from building a genuine movement based on the enjoyment of life, diversity, practical self-determination and multi-faceted resistance to the Babylonian Pigocracy. This Pigocracy is in our 'heads,' our relationships as well as in the institutions that have a vested interest in our eternal domination.[50]

Independence anarchism

Independence anarchism (also known as anarcho-independentism) attempts to synthesise certain aspects of national liberation movements with an opposition to hierarchical institutions grounded in libertarian socialism. Where a certain nation or people exists with its own distinct language, culture and self-identity, independence anarchists concur with supporters of nationalism that such a nation is entitled to self-determination. While statist nationalists advocate the resolution of national questions by the formation of new states, independence anarchists advocate self-government without the need for a state and are committed to the key anarchist societal principles of federalisation, mutual aid and anarchist economics. Some supporters of the movement defend its position as a tactical one, arguing that secessionism and self-organisation is a particularly effective strategy with which to challenge state power.[52]

Independence anarchism frames national questions primarily in terms of equality, and the right of all peoples to cultural autonomy, linguistic rights, etc. Being grounded in such concepts, independence anarchism is strongly opposed to racism, xenophobia, national supremacism and isolationism of any kind, favouring instead internationalism and cooperation between peoples. Independence anarchists also stand opposed to homogenisation within cultures, holding diversity as a core principle. Those who identify as part of the tendency may also ground their position in a commitment to anti-racism (postcolonial anarchism), class struggle (anarcho-communism and anarcho-syndicalism), ecology (green anarchism), feminism (anarcha-feminism) and LGBT liberation (queer anarchism).[53]

Post-colonial anarchism

Post-colonial anarchism is a relatively new tendency within the larger anarchist movement. The name is taken from an essay by Roger White, one of the founders of Jailbreak Press and an activist in North American Anarchist People of Color (APOC) circles. Post-colonial anarchism is an attempt to bring together disparate aspects and tendencies within the existing anarchist movement and re-envision them in an explicitly anti-imperialist framework.

Where traditional anarchism is a movement arising from the struggles of proletarians in industrialized western European nations and sees history from this perspective, post-colonial anarchism approaches the same principles of class struggle, mutual aid and opposition to social hierarchy as well as support for community-level self-determination, self-government and self-management from the perspective of colonized peoples throughout the world. In doing so, post-colonial anarchism does not seek to invalidate the contributions of the more established anarchist movement, but rather it seeks to add a unique and important perspective. The tendency is strongly influenced by anti-statist forms of left-wing nationalism, APOC and indigenism, among other sources.

References

- 1 2 Firth, Will. "Esperant Kaj Anarkiismo". Nodo50. Retrieved 21 September 2020. "Anarkiistoj estis inter la pioniroj de la disvastigo de Esperanto. En 1905 fondiĝis en Stokholmo la unua anarkiisma Esperanto-grupo. Sekvis multaj aliaj: en Bulgario, Ĉinio kaj aliaj landoj. Anarkiistoj kaj anarki-sindikatistoj, kiuj antaŭ la Unua Mondmilito apartenis al la nombre plej granda grupo inter la proletaj esperantistoj, fondis en 1906 la internacian ligon Paco-Libereco, kiu eldonis la Internacian Socian Revuon. Paco-libereco unuiĝis en 1910 kun alia progresema asocio, Esperantista Laboristaro. La komuna organizaĵo nomiĝis Liberiga Stelo. Ĝis 1914 tiu organizaĵo eldonis multe da revolucia literaturo en Esperanto, interalie ankaŭ anarkiisma. Tial povis evolui en la jaroj antaŭ la Unua Mondmilito ekzemple vigla korespondado inter eŭropaj kaj japanaj anarkiistoj. En 1907 la Internacia Anarkiisma Kongreso en Amsterdamo faris rezolucion pri la afero de internacia lingvo, kaj venis dum la postaj jaroj similaj kongresaj rezolucioj. Esperantistoj, kiuj partoprenis tiujn kongresojn, okupiĝis precipe pri la internaciaj rilatoj de la anarkiistoj."

- 1 2 Roselló, Josep Maria Roselló (17 August 2005). "Dossier: El naturalismo libertario en la península ibérica (1890-1939)". Ekintza Zuzena. No. 32. Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2014.

Proliferarán así diversos grupos que practicarán el excursionismo, el naturismo, el nudismo, la emancipación sexual o el esperantismo, alrededor de asociaciones informales vinculadas de una manera o de otra al anarquismo. Precisamente las limitaciones a las asociaciones obreras impuestas desde la legislación especial de la Dictadura potenciarуán indirectamente esta especie de asociacionismo informal en que confluirá el movimiento anarquista con esta heterogeneidad de prácticas y tendencias. Uno de los grupos más destacados, que será el impulsor de la revista individualista Ética será el Ateneo Naturista Ecléctico, con sede en Barcelona, con sus diferentes secciones la más destacada de las cuales será el grupo excursionista Sol y Vida.

- 1 2 Díez, Xavier (1 April 2006). "La insumisión voluntaria. El anarquismo individualista español durante la Dictadura y la Segunda República (1923-1938)" (PDF). pp. 1–36. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 6 May 2011.

La insumisión voluntaria: El anarquismo individualista español durante la Dictadura y la Segunda República (1923–1938).

- ↑ Del Barrio, Toño; Lins, Ulrich (27–29 November 2006). "La utilización del esperanto durante la Guerra Civil Española". Nodo50. International Congress on the Spanish Civil War. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- 1 2 Flood, Andrew. "An Anarchist Perspective on Irish Nationalism". Workers Solidarity Movement.

- 1 2 "Against Nationalism". Anarchist Federation. 3 April 2009. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- ↑ Woodcock, George. Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. p. 233.

- ↑ Proudhon, Pierre-Joseph. General Idea of the Revolution in the Nineteenth Century. p. 283.

- ↑ Perlman, Fredy (1983). Anti-Semitism and the Beirut Pogrom by Fredy Perlman. Detroit: Black & Red. ISBN 9780939306077.

- ↑ Perlman, Fredy (1985). The Continuing Appeal of Nationalism. Detroit: Black & Red. ISBN 9780934868273.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Perlman, Fredy (Winter 1984). "The Continuing Appeal of Nationalism". Fifth Estate. Retrieved 20 September 2010 – via Libcom.org.

- ↑ Bakunin 1848.

- ↑ Knowles n.d.

- ↑ Billingsley n.d.

- ↑ Nettlau 1953.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Macklin, Graham D. (September 2005). "Co-opting the counter culture: Troy Southgate and the National Revolutionary Faction". Patterns of Prejudice. 39 (3): 301–326. doi:10.1080/00313220500198292. S2CID 144248307.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Sunshine, Spencer (Winter 2008). "Rebranding Fascism: National-Anarchists". The Public Eye. 23 (4): 1–12. Retrieved 12 November 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Sanchez, Casey (Summer 2009). "California Racists Claim They're Anarchists". Intelligence Report. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- 1 2 3 Griffin, Roger (March 2003). "From slime mould to rhizome: an introduction to the groupuscular right". Patterns of Prejudice. 37 (1): 27–63. doi:10.1080/0031322022000054321. S2CID 143709925.

- 1 2 Goodrick-Clarke, Nicholas (2003). Black Sun: Aryan Cults, Esoteric Nazism and the Politics of Identity. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-3155-0.

- 1 2 Sykes, Alan (2005). The Radical Right in Britain: Social Imperialism to the BNP (British History in Perspective). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-59923-5.

- ↑ Lyons, Matthew N. (Summer 2011). "Rising Above the Herd: Keith Preston's Authoritarian Anti-Statism". New Politics. 7 (3). Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- ↑ Flood, Andrew. "Insurrection in Ireland". Anarkismo.net. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- ↑ "The Republican Tradition - A Place to Build From?". World Socialist Movement. 26 November 2010. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ↑ Puri 1983.

- ↑ Aldred 1948.

- ↑ Pascual, Jakue (27 October 2011). "Aizkora eta sugea". Anarkherria. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ↑ Sysyn 1977, p. 279.

- ↑ Sysyn 1977, pp. 279–280.

- ↑ Sysyn 1977, p. 280.

- ↑ Sysyn 1977, pp. 280–281.

- ↑ Sysyn 1977, p. 284.

- ↑ Sysyn 1977, pp. 284–285.

- ↑ Sysyn 1977, pp. 285–286.

- ↑ Sysyn 1977, p. 286.

- ↑ Sysyn 1977, p. 287.

- ↑ Sysyn 1977, pp. 287–288.

- ↑ Sysyn 1977, p. 288.

- ↑ Sysyn 1977, pp. 288–289.

- ↑ Sysyn 1977, p. 289.

- ↑ Sysyn 1977, pp. 289–290.

- ↑ Sysyn 1977, pp. 290–292.

- ↑ Sysyn 1977, p. 292.

- ↑ Sysyn 1977, p. 293.

- ↑ Sysyn 1977, pp. 293–294.

- ↑ Sysyn 1977, p. 294.

- ↑ Sysyn 1977, p. 303.

- ↑ Sysyn 1977, pp. 303–304.

- ↑ "Senzala or Quilombo: Reflections on APOC and the fate of Black Anarchism". Anarkismo. 11 May 2005. Retrieved 20 September 2010.

- ↑ Alston, Ashanti (October 1999). @narchist Panther Zine. 1 (1).

- ↑ Negres Tempestes (20 March 2006). "Negres Tempestes Presentation". Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ↑ "Qui som". Negres Tempestes. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ↑ AAVV. Anarquisme i alliberament nacional. ISBN 978-84-96044-90-6.

Bibliography

- Aldred, Guy (1948). Rex v. Aldred. Glasgow: Strickland Press.

- Bakunin, Mikhail (1848). Appeal to the Slavs. In Dolgoff, Sam (1971). Bakunin on Anarchy.

- Billingsley, Philip (n.d.). "Bakunin, Yokohama and the Dawning of the Pacific Era".

- Gordon, Uri (2017). "Anarchism and Nationalism". In Jun, Nathan (ed.). Brill's Companion to Anarchism and Philosophy. Leiden: Brill. pp. 196–215. doi:10.1163/9789004356894_009. ISBN 978-90-04-35689-4.

- Hampson, Norman (1968). The Enlightenment. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

- Hearder, Harry (1966). Europe in the Nineteenth Century 1830–1880. New York: Longman. ISBN 0-582-48212-7.

- Knowles, Rob (n.d.). "Anarchist Notions of Nationalism and Patriotism". R.A. Forum.

- Motherson, Keith (5 September 1980). "The Ice Floes are Melting: The State of the Left". Peace News. (2127): 9–11.

- Nettlau, Max (1953). "Mikhail Bakunin: A Biographical Sketch". In Maximoff, Gregori. The Political Philosophy of Bakunin: Scientific Anarchism. 42. The Free Press.

- Puri, Karish K. (1983). Ghadar Movement: Ideology, Organisation and Strategy. Guru Nanak Dev University Press.

- Rocker, Rudolf (1998). Nationalism and Culture (reprint 1937 ed.). Black Rose Books.

- Sparrow, Robert (2007). "For the Union Makes Us Strong: Anarchism and Patriotism". In Primoratz, Igor; Pavković, Aleksandar (eds.). Patriotism: Philosophical and Political Perspectives. Aldershot: Ashgate. pp. 201–217. ISBN 978-0-7546-7122-0. LCCN 2007034129. OCLC 318534708.

- Sysyn, Frank (1977). "Nestor Makhno and the Ukrainian Revolution". In Hunczak, Taras (ed.). The Ukraine, 1917–1921: A Study in Revolution. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 271–304. ISBN 9780674920095. OCLC 942852423. Archived from the original on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- West, Pat V. T. (23 September 2005). "Obituary: Monica Sjoo". The Guardian.

External links

- Alston, Ashanti. "Beyond Nationalism, But Not Without It". Discussing nationalism and anarchism from a black anarchist perspective

- "Anarchists Against Nationalism". Flag.blackened.net.

- "Anarchists and Nationalism". Flag.blackened.net.

- "Are anarchists against nationalism?". Spunk Library.

- Home, Stewart. "Anarchist Integralism".

- Knowles, Rob. "Anarchist Notions of Nationalism and Patriotism".

- Perlman, Fredy. The Continuing Appeal of Nationalism

- White, Roger. "Post Colonial Anarchism". Discussing anarchism, nationalism and national liberation from an APOC perspective.