The history of cannabis and its usage by humans dates back to at least the third millennium BC in written history, and possibly as far back as the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (8800–6500 BCE) based on archaeological evidence. For millennia, the plant has been valued for its use for fiber and rope, as food and medicine, and for its psychoactive properties for religious and recreational use.

The earliest restrictions on cannabis were reported in the Islamic world by the 14th century. In the 19th century, it began to be restricted in colonial countries, often associated with racial and class stresses. In the middle of the 20th century, international coordination led to sweeping restrictions on cannabis throughout most of the globe. Entering the 21st century, some nations began to take measures to decriminalize or legalize cannabis.

Ancient uses

.jpg.webp)

Hemp is possibly one of the earliest plants to be cultivated.[4][5] Cannabis has been cultivated in Japan since the pre-Neolithic period for its fibres and as a food source and possibly as a psychoactive material.[6]: 96 An archeological site in the Oki Islands near Japan contained cannabis achenes from about 8000 BC, probably signifying use of the plant.[7] Hemp use archaeologically dates back to the Neolithic Age in China, with hemp fiber imprints found on Yangshao culture pottery dating from the 5th millennium BC.[2][8] The Chinese later used hemp to make clothes, shoes, ropes, and an early form of paper.[2]

Cannabis was an important crop in ancient Korea, with samples of hempen fabric discovered dating back as early as 3000 BC.[9]

Cannabis is believed to be consumed by Hindu God Shiva, and has been part of Hindu practice and culture.[10]

Hemp is called ganja (Sanskrit: गञ्जा, IAST: gañjā) in Sanskrit and other modern Indo-Aryan languages.[11] Some scholars suggest that the ancient drug soma, mentioned in the Vedas, was cannabis, although this theory is disputed.[12] Bhanga is mentioned in several Indian texts dated before 1000 AD. However, there is philological debate among Sanskrit scholars as to whether this bhanga can be identified with modern bhang or cannabis.[13]

Cannabis was also known to the ancient Assyrians, who potentially utilized it as an aromatic. They called it qunabu and qunubu (which could signify "a way to produce smoke"), a potential origin of the modern word "cannabis".[14]: 305 Cannabis was introduced as well to the Scythians, Thracians and Dacians, whose shamans (the kapnobatai—"those who walk on smoke/clouds") burned cannabis flowers to induce trance.[15] The classical Greek historian Herodotus (ca. 480 BC) reported that the inhabitants of Scythia would often inhale the vapors of hemp-seed smoke, both as ritual and for their own pleasurable recreation.[16]

Cannabis residues have been found on two altars in Tel Arad, dated to the Kingdom of Judah in the 8th century BC.[17] Its discoverers believe that the evidence points to the use of cannabis for ritualistic psychoactive use in Judah.[17] According to Zohar Amar the fact that the Tel Arad altar was eventually closed down (apparently due to religious opposition by Hezekiah), and the Biblical prohibition on priestly service while intoxicated by wine (Leviticus 10:8–11), indicate that Israelite religion in general was probably opposed to cannabis use as part of its priestly services.[18]

Cannabis has an ancient history of ritual use and is found in pharmacological cults around the world. Hemp seeds discovered by archaeologists at Pazyryk suggest early ceremonial practices like eating by the Scythians occurred during the 5th to 2nd century BC confirming previous historical reports by Herodotus.[19] In China, the psychoactive uses of cannabis is described in the Shennong Bencaojing, written around the 3rd century AD.[20] Daoists mixed cannabis with other ingredients, then placed them in incense burners and inhaled the smoke.[20]

Global spread

Around the turn of the second millennium, the use of hashish (cannabis resin) began to spill over from the Persian world into the Arab world. Cannabis was allegedly introduced to Iraq in 1230 AD, during the reign of Caliph Al-Mustansir Bi'llah, by the entourage of Bahraini rulers visiting Iraq.[21] Hashish was introduced to Egypt by "mystic Islamic travelers" from Syria sometime during the Ayyubid dynasty in the 12th century AD.[6]: 234 [22] Hashish consumption by Egyptian Sufis has been documented as occurring in the thirteenth century AD, and a unique type of cannabis referred to as Indian hemp was also documented during this time.[6]: 234 Smoking did not become common in the Old World until after the introduction of tobacco, so up until the 1500s hashish in the Muslim world was consumed as an edible.[23]

Cannabis is thought to have been introduced to Africa by Indian Hindu travelers, which Bantu settlers subsequently introduced to southern Africa when they migrated southward.[24] Smoking pipes uncovered in Ethiopia and carbon-dated to around 1320 AD were found to have traces of cannabis.[25] It was already in popular use in South Africa by the indigenous[26] Khoisan and Bantu peoples prior to European settlement in the Cape in 1652.[27] By the 1850s, Swahili traders had carried cannabis from the east coast of Africa, to the Congo Basin in the west.[25]: 99

King Henry VIII of England strongly encouraged hemp cultivation in the early sixteenth century, particularly for its use by the expanding English navy.[28]

In the Western Hemisphere, early Spanish Florida explorer Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, describing the many tribes of native peoples he encountered between 1527-1537, wrote "Throughout the country they get inebriated [also translated as 'become drunk' and 'produce stupefaction'] by using a certain smoke, and will give everything they have in order to get it."[29] The Spaniards brought industrial hemp to the Western Hemisphere and cultivated it in Chile starting about 1545.[30] In 1607, "hempe" was among the crops Gabriel Archer observed being cultivated by the natives at the main Powhatan village, where Richmond, Virginia is now situated;[31] and in 1613, Samuell Argall reported wild hemp "better than that in England" growing along the shores of the upper Potomac. As early as 1619, the first Virginia House of Burgesses passed an Act requiring all planters in Virginia to sow "both English and Indian" hemp on their plantations.[32]

During Napoléon Bonaparte's invasion of Egypt in 1798, alcohol was not available per Egypt being an Islamic country.[33] In lieu of alcohol, Bonaparte's troops resorted to trying hashish, which they found to their liking.[33] Following an 1836–1840 travel in North Africa and the Middle East, French physician Jacques-Joseph Moreau wrote on the psychological effects of cannabis use; Moreau was a member of Paris' Club des Hashischins (founded in 1844). In 1842, Irish physician William Brooke O'Shaughnessy, who had studied the drug while working as a medical officer in Bengal with the East India company, brought a quantity of cannabis with him on his return to Britain, provoking renewed interest in the West.[34] Examples of classic literature of the period featuring cannabis include Les paradis artificiels (1860) by Charles Baudelaire and The Hasheesh Eater (1857) by Fitz Hugh Ludlow.

Early restrictions

Jurisdictions around the world banned cannabis at various times since the Middle Ages. Perhaps the earliest was Soudoun Sheikouni, the emir of the Joneima in Arabia who prohibited use in the 1300s.[35] In 1787, King Andrianampoinimerina of Madagascar took the throne, and soon after banned cannabis throughout the Merina Kingdom, implementing capital punishment as the penalty for its use.[36]

As European colonial powers absorbed or came into contact with cannabis-consuming regions, the cannabis habit began to spread to new areas under the colonial umbrella, causing some alarm among authorities. After his invasion of Egypt Syria (1798-1801), Napoleon banned cannabis use among his soldiers.[37] Cannabis was introduced to Brazil either by the Portuguese colonists or by African slaves[6] in the early 1800s. Their intent may have been to cultivate hemp fiber, but the slaves the Portuguese imported from Africa were familiar with cannabis and used it psychoactively, leading the Municipal Council of Rio de Janeiro in 1830 to prohibit bringing cannabis into the city, and punishing its use by any slave.[6]: 182 Similarly, the British practice of transporting Indian indentured workers throughout the empire had the result of spreading the longstanding cannabis practices. Concerns about use of gandia by laborers led to a ban in British Mauritius in 1840,[38] and use of ganja by Indian laborers in British Singapore[39] led to its banning there in 1870.[40] In 1870, Natal (now in South Africa) passed the Coolie Law Consolidation prohibiting "the smoking, use, or possession by and the sale, barter, or gift to, any Coolies [Indian indentured workers] whatsoever, of any portion of the hemp plant (Cannabis sativa)..."[41]

Attempts at criminalising cannabis in British India were made, and mooted, in 1838, 1871, and 1877.[42] In 1894, the British Indian government completed a wide-ranging study of cannabis in India. The report's findings stated:

Viewing the subject generally, it may be added that the moderate use of these drugs is the rule, and that the excessive use is comparatively exceptional. The moderate use practically produces no ill effects. In all but the most exceptional cases, the injury from habitual moderate use is not appreciable. The excessive use may certainly be accepted as very injurious, though it must be admitted that in many excessive consumers the injury is not clearly marked. The injury done by the excessive use is, however, confined almost exclusively to the consumer himself; the effect on society is rarely appreciable. It has been the most striking feature in this inquiry to find how little the effects of hemp drugs have obtruded themselves on observation.

— Report of the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission, 1894-1895[43]

In the late 1800s, several countries in the Islamic world and its periphery banned cannabis, with the Khedivate of Egypt banning the importation of cannabis in 1879,[44][45] Morocco strictly regulating cannabis cultivation and trade (while allowing several Rif tribe to continue to produce) in 1890,[46] and Greece's ban on hashish in 1890.[47]

At the start of the 20th century, more countries continued to ban cannabis. In the United States, the first restrictions on sale of cannabis came in 1906 (in District of Columbia).[48] It was outlawed by the Ganja Law in Jamaica (then a British colony) in 1913, in South Africa in 1922, and in the United Kingdom and New Zealand in the 1920s.[49] Canada criminalized cannabis in The Opium and Narcotic Drug Act, 1923,[50] before any reports of the use of the drug in Canada.

In the United States in 1937, the Marihuana Tax Act was passed,[51] and prohibited the production of hemp in addition to cannabis. The reasons that hemp was also included in this law are disputed—several scholars have claimed that the act was passed in order to destroy the US hemp industry,[52][53][54] Shortly thereafter the United States was forced back to promoting rather than discouraging hemp cultivation; hemp was used extensively by the United States during World War II to make uniforms, canvas, and rope.[55] Much of the hemp used was cultivated in Kentucky and the Midwest. During World War II, the U.S. produced a short 1942 film, Hemp for Victory, promoting hemp as a necessary crop to win the war. In Western Europe, the cultivation of hemp was not legally banned by the 1930s, but the commercial cultivation stopped by then, due to decreased demand compared to increasingly popular artificial fibers.[56] In the early 1940s, world production of hemp fiber ranged from 250,000 to 350,000 metric tonnes, Russia was the biggest producer.[52][57]

International regulation

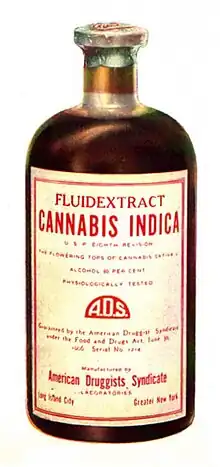

In 1925 a compromise was made at an international conference in Geneva about the Second International Opium Convention that banned exportation of "Indian hemp" to countries that had prohibited its use, and requiring importing countries to issue certificates approving the importation and stating that the shipment was required "exclusively for medical or scientific purposes". It also required parties to "exercise an effective control of such a nature as to prevent the illicit international traffic in Indian hemp and especially in the resin".[58][59] However, the controls applied only to pure extract and tincture, not to derivatives and medicinal preparations. In 1935, after complaints from Egypt about cannabis-containing medicines sold by Parke-Davis, the health branch of the League of Nations (International Office of Public Hygiene) granted countries the right to submit medicinal products containing cannabis to similar controls as those of pure extracts and tinctures under the 1925 Opium Convention.[60]

In 1925, in parallel, cannabis herb, extract, and tincture, appeared in the Second Brussels Agreement for the harmonization of pharmacopeias, a treaty precursor to the International Pharmacopoeia.[61]

Shortly after World War II, a World Health Organization (WHO) committee withdrew cannabis and other herbal medicines from the international pharmacopoeia.[62] Between 1952 and 1960, another WHO committee emitted repeated negative conclusions regarding the therapeutic utility of cannabis.[63] Coupled with a strong political determination from a number of countries, these events laid ground for the placement of "cannabis and cannabis resin" in Schedule IV of the quasi-universally ratified 1961 Convention on narcotic drugs,[64] Schedule IV being the most restrictive level of international mandatory control listing the most harmful substances.

Liberalizing and legalizing

In 1972, the Dutch government divided drugs into more- and less-dangerous categories, with cannabis being in the lesser category. Accordingly, possession of 30 grams or less was made a misdemeanor.[65] Cannabis has been available for recreational use in coffee shops since 1976.[66] Cannabis products are only sold openly in certain local "coffeeshops" and possession of up to 5 grams for personal use is decriminalised, however: the police may still confiscate it, which often happens in car checks near the border. Other types of sales and transportation are not permitted, although the general approach toward cannabis was lenient even before official decriminalisation.[67][68][69]

Cannabis began to attract renewed interest as medicine in the 1970s and 1980s, in particular due to its use by cancer and AIDS patients who reported relief from the effects of chemotherapy and wasting syndrome.[70] In 1996, California became the first U.S. state to legalize medical cannabis in defiance of federal law.[71] In 2001, Canada became the first country to adopt a system regulating the medical use of cannabis.[72]

In 2001, Portugal decriminalized all drugs, maintaining the prohibition on production and sale, but changing personal possession and use from a criminal offense to an administrative one.[73] Subsequently, a number of European and Latin American countries decriminalized cannabis, such as Belgium (2003),[74] Chile (2005),[75] Brazil (2006),[76] and the Czech Republic (2010).[77]

In Uruguay, President Jose Mujica signed legislation to legalize recreational cannabis in December 2013, making Uruguay the first country in the modern era to legalize cannabis. In August 2014, Uruguay legalized growing up to six plants at home, as well as the formation of growing clubs, a state-controlled marijuana dispensary regime. In Canada, following the 2015 election of Justin Trudeau and formation of a Liberal government, in 2017 the House of Commons passed a bill to legalize cannabis on 17 October 2018.[78]

Some U.S. states have legalized marijuana, but Peter Reuter argues that restricting promotion of marijuana once it is legal is more complex than it may initially appear.[79]

The United Nations' World Drug Report stated that cannabis "was the world's most widely produced, trafficked, and consumed drug in the world in 2010", identifying that between 128 million and 238 million users globally in 2015.[80][81]

Between 2018 and 2019, the WHO undertook its first scientific evidence-based assessment of cannabis, recommending the removal of cannabis and cannabis resin from Schedule IV of the Single Convention.[63] A United Nations commission voted in December 2020 to approve the change in treaty scheduling.[82]

See also

References

- ↑ Alison Matthews; Laurence Matthews (2007). Tuttle Learning Chinese Characters: A Revolutionary New Way to Learn and Remember the 800 Most Basic Chinese Characters. Tuttle Publishing. p. 336. ISBN 978-0-8048-3816-0. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- 1 2 3 Peter G. Stafford; Jeremy Bigwood (1992). Psychedelics Encyclopedia. Ronin Publishing. ISBN 978-0-914171-51-5. Archived from the original on 14 February 2017. Retrieved 18 December 2017.: 157

- ↑ Staelens, Stefanie. "The Bhang Lassi Is How Hindus Drink Themselves High for Shiva". Vice.com. Archived from the original on 11 August 2017. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- ↑ "Information paper on industrial hemp (industrial cannabis)". Department of Primary Industries and Fisheries, Queensland Government. Archived from the original on 23 July 2008. Retrieved 5 July 2008.

- ↑ Ethan Russo (August 2007). "History of cannabis and its preparations in saga, science, and sobriquet". Chemistry & Biodiversity. 4 (8): 1614–1648. doi:10.1002/cbdv.200790144. PMID 17712811. S2CID 42480090.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Robert C. Clarke; Mark D. Merlin (1 September 2013). Cannabis: Evolution and Ethnobotany. Univ of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-27048-0. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ↑ Tengwen Long; et al. (March 2017). "Cannabis in Eurasia: origin of human use and Bronze Age trans-continental connections". Vegetation History and Archaeobotany. 26 (2): 245–258. doi:10.1007/s00334-016-0579-6. S2CID 133420222.

- ↑ Barber, E. J. W. (1992). Prehistoric Textiles: The Development of Cloth in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages with Special Reference to the Aegean. Princeton University Press. p. 17.

- ↑ Chris Duvall (15 November 2014). Cannabis. Reaktion Books. pp. 30–. ISBN 978-1-78023-386-4. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ↑ Acharya, S L; Howard, J; Panta, S B; Mahatma, S S; Copeland, J (31 March 2015). "Cannabis, Lord Shiva and Holy Men: Cannabis Use Among Sadhus in Nepal". Journal of Psychiatrists' Association of Nepal. 3 (2): 9–14. doi:10.3126/jpan.v3i2.12379. ISSN 2350-8949. Archived from the original on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ↑ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 264.

- ↑ Rudgley, Richard (1998). Little, Brown; et al. (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Substances. ISBN 978-0-349-11127-8. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ↑ Ethan Russo (2006). Raphael Mechoulam (ed.). Cannabis in India: ancient lore and modern medicine (PDF). Springer. pp. 3–5. ISBN 9783764373580. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Rubin, Vera D (1976). Cannabis and Culture. Campus Verlag. ISBN 978-3-593-37442-0.

- ↑ Cunliffe, Barry W (2001). The Oxford Illustrated History of Prehistoric Europe. Oxford University Press. p. 405. ISBN 978-0-19-285441-4.

- ↑ Herodotus. Histories. Vol. IV. 73–75.

- 1 2 Eran Arie; Baruch Rosen; Dvory Namdar (2020). "Cannabis and Frankincense at the Judahite Shrine of Arad". Tel Aviv. 47 (1): 5–28. doi:10.1080/03344355.2020.1732046.

- ↑ "בבית המקדש לא עישנו קנביס". Archived from the original on 14 November 2022. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ↑ Walton, Robert P (1938). Marijuana, America's New Drug Problem. JB Lippincott. p. 6.

- 1 2 Rudgley, Richard (2005). Prance, Ghillean; Nesbitt, Mark (eds.). The Cultural History of Plants. Routledge. p. 198. ISBN 0415927463.

- ↑ Franz Rosenthal (1971). زهر العريش في احكام الحشيش: Haschish Versus Medieval Muslim Society. Brill Archive. pp. 53–. GGKEY:PXU3DXJBE76. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ↑ "Timeline: the use of cannabis". BBC News. 16 June 2005. Archived from the original on 28 April 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ↑ John Charles Chasteen (9 February 2016). Getting High: Marijuana through the Ages. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 72–. ISBN 978-1-4422-5470-1. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ↑ Watt, John Mitchell (1 January 1961). "UNODC - Bulletin on Narcotics - 1961 Issue 3 - 002". United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Archived from the original on 8 November 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- 1 2 Vera Rubin (1 January 1975). Cannabis and Culture. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 77–. ISBN 978-3-11-081206-0. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

Cannabis Smoking in 13th-14th Century Ethiopia: Chemical Evidence

- ↑ de Vos, Pierre (4 May 2017). "Dagga judgment: there are less drastic ways to deal with its harmful effects". Constitutionally Speaking. Archived from the original on 18 June 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- ↑ Kings, Sipho (28 February 2014). "The war on dagga sobers up". The M&G Online. Archived from the original on 9 September 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- ↑ Clarke, R.; Merlin, M. (2016). Cannabis: Evolution and Ethnobotany. University of California Press. p. 179. ISBN 978-0-520-29248-2. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ↑ Cabeza de Vaca, Alvar; de Vaca, M. (1547). The Narrative of Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca. University of California Libraries. p. 84. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ↑ Daryl T. Ehrensing (May 1998). "Feasibility of Industrial Hemp Production in the United States Pacific Northwest, SB681". Oregon State University. Archived from the original on 15 November 2017. Retrieved 15 May 2016.

- ↑ Gabriel Archer, A Relatyon of the Discoverie of Our River..., printed in Archaeologia Americana 1860, p. 44. William Strachey (1612) records a native (Powhatan) name for hemp (weihkippeis).

- ↑ Proceedings of the Virginia Assembly, 1619 Archived 2003-03-04 at the Wayback Machine, cf. the 1633 Act: Hening's Statutes at Large, p. 218 Archived 14 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 Booth, M. (2015). Cannabis: A History. St. Martin's Press. pp. 76–77. ISBN 978-1-250-08219-0. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ↑ Leslie L. Iversen (7 December 2007). The Science of Marijuana. Oxford University Press. pp. 110–. ISBN 978-0-19-988693-7. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ↑ Bankole A. Johnson (10 October 2010). Addiction Medicine: Science and Practice. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 303–. ISBN 978-1-4419-0338-9. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- ↑ Gwyn Campbell (3 April 2012). David Griffiths and the Missionary "History of Madagascar". BRILL. pp. 437–. ISBN 978-90-04-20980-0.

- ↑ Booth, M. (2015). Cannabis: A History. St. Martin's Press. pp. 76–77. ISBN 978-1-250-08219-0.

- ↑ A Collection of the Laws of Mauritius and Its Dependencies. By the authority of the Government. 1867. pp. 541–. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ↑ Stanley Einstein (1980). The Community's response to drug use. Pergamon Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-08-019597-1. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ↑ Nanthawan Bunyapraphatsō̜n (1999). Medicinal and poisonous plants. Backhuys Publishers. p. 169. ISBN 978-90-5782-042-7.

- ↑ Brian M. Du Toit (1991). Cannabis, alcohol, and the South African student: adolescent drug use, 1974-1985. Ohio University Center for International Studies. ISBN 978-0-89680-166-0. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ↑ A Cannabis Reader: Global Issues and Local Experiences : Perspectives on Cannabis Controversies, Treatment and Regulation in Europe. European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. 2008. p. 100. ISBN 978-92-9168-311-6. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ↑ "(298) Page 264 - India Papers > Medicine - Drugs > Report of the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission, 1894-1895 > Volume I - Medical History of British India - National Library of Scotland". nls.uk. Archived from the original on 13 July 2015. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ↑ India. Hemp Drugs Commission (1893–1894); Sir William Mackworth Young (1969). Marijuana: Report of the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission, 1893–1894. Thos. Jefferson Publishing Company. p. 270. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ E.L. Abel (29 June 2013). Marihuana: The First Twelve Thousand Years. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 133–. ISBN 978-1-4899-2189-5. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ↑ Söderbaum, Fredrik; Ian Taylor; Nordiska Afrikainstitutet (2008). Afro-regions: The Dynamics of Cross-border Micro-regionalism in Africa. Stylus Pub Llc. p. 130. ISBN 978-91-7106-618-3. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ↑ E.L. Abel (29 June 2013). Marihuana: The First Twelve Thousand Years. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 135–. ISBN 978-1-4899-2189-5. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ↑ "Statement of Dr. William C. Woodward". Drug library. Archived from the original on 26 October 2017. Retrieved 20 September 2010.

- ↑ "Debunking the Hemp Conspiracy Theory". Archived from the original on 16 September 2009. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ↑ The Opium and Narcotic Drug Act, 1923, S.C. 1923, c. 22

- ↑ Pub. L. 75–238, 50 Stat. 551, enacted August 2, 1937

- 1 2 Laurence Armand French; Magdaleno Manzanárez (2004). Nafta & Neocolonialism: Comparative Criminal, Human & Social Justice. University Press of America. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-7618-2890-7. Archived from the original on 28 December 2019. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ↑ Mitch Earleywine (2002). Understanding Marijuana: A New Look at the Scientific Evidence. Oxford University Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-19-513893-1. Archived from the original on 10 January 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ↑ Preston Peet (2004). Under The Influence: The Disinformation Guide To Drugs. Consortium. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-932857-00-9. Archived from the original on 11 January 2017. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ↑ Armagnac, Alden P. (September 1943). "Plant Wizards Fight Wartime Drug Peril". Popular Science. pp. 62–63. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ↑ "Dr. Ivan BÛcsa, GATE Agricultural Research Institute, Kompolt - Hungary, Book Review Re-discovery of the Crop Plant Cannabis Marihuana Hemp (Die Wiederentdeckung der Nutzplanze Cannabis Marihuana Hanf)". Hempfood.com. Archived from the original on 21 December 2012. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ↑ Dewey LH (1943). "Fiber production in the western hemisphere". United States Printing Office, Washington. p. 67. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ↑ W. W. Willoughby (1925). "Opium as an international problem". Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press. Archived from the original on 30 November 2010. Retrieved 20 September 2010.

- ↑ Opium as an international problem: the Geneva conferences – Westel Woodbury Willoughby at Google Books

- ↑ "Cannabis amnesia – Indian hemp parley at the Office International d'Hygiène Publique in 1935 - Authorea". www.authorea.com. doi:10.22541/au.165237542.24089054/v1. Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ↑ Riboulet-Zemouli, Kenzi (2020). "'Cannabis' ontologies I: Conceptual issues with Cannabis and cannabinoids terminology". Drug Science, Policy and Law. 6: 205032452094579. doi:10.1177/2050324520945797. ISSN 2050-3245.

- ↑ Volckringer, Jean (1953). Evolution et unification des formulaires et des pharmacopées (in French). Paris: Paul Brandouy. p. 289.

- 1 2 Riboulet-Zemouli, Kenzi; Krawitz, Michael Alan (1 January 2022). "WHO's first scientific review of medicinal Cannabis: from global struggle to patient implications". Drugs, Habits and Social Policy. 23 (1): 5–21. doi:10.1108/DHS-11-2021-0060. ISSN 2752-6747.

- ↑ Mills, James H. (7 December 2016). "The IHO as Actor The case of cannabis and the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs 1961". Hygiea Internationalis. 13 (1): 95–115. doi:10.3384/hygiea.1403-8668.1613195. ISSN 1404-4013. PMC 6440645. PMID 30930679.

- ↑ Martin Booth (1 June 2005). Cannabis: A History. Picador. pp. 338–. ISBN 978-0-312-42494-7. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ↑ Michael Tonry (22 September 2015). Crime and Justice, Volume 44: A Review of Research. University of Chicago Press. pp. 261–. ISBN 978-0-226-34102-6. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ↑ "Use drop-down menu on site to view Netherlands entry.)". Eldd.emcdda.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 7 May 2010. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

- ↑ "Drugs Policy in the Netherlands". Ukcia.org. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

- ↑ "Amsterdam Will Ban Tourists from Pot Coffee Shops". Atlantic Wire. 27 May 2011. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

- ↑ Joy, Janet E.; Watson, Stanley J.; Benson, John A. (1999). "Marijuana and Medicine -- Assessing the Science Base" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 January 2018. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ↑ "History of Marijuana as Medicine – 2900 BC to Present". ProCon.org. Archived from the original on 15 July 2017. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ "Marijuana's journey to legal health treatment: the Canadian experience". CBC News. 17 August 2009. Archived from the original on 14 June 2017. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ "EMCDDA:Drug policy profiles, Portugal, June 2011". Emcdda.europa.eu. 17 August 2011. Archived from the original on 17 September 2019. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

- ↑ Police fdrale - CGPR Webteam. "Federale politie - Police fdrale". Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- ↑ TNI. "Chile - Drug Law Reform in Latin America". Archived from the original on 6 October 2018. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- ↑ Professor Anita Kalunta-Crumpton (28 June 2015). Pan-African Issues in Drugs and Drug Control: An International Perspective. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 242–. ISBN 978-1-4724-2214-9. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ↑ Carney, Sean (8 December 2009). "Czech Govt Allows 5 Cannabis Plants For Personal Use From 2010 - Emerging Europe Real Time". The Wall Street Journal Emerging Europe blog. Archived from the original on 7 April 2011. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- ↑ "Federal marijuana legislation clears House of Commons, headed for the Senate | CBC News". Archived from the original on 19 December 2017. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ↑ Reuter, Peter (March 2014). "The difficulty of restricting promotion of legalized marijuana in the United States: Commentaries". Addiction. 109 (3): 353–354. doi:10.1111/add.12431. PMID 24524313.

- ↑ Eliana Dockterman (29 June 2012). "Marijuana Now the Most Popular Drug in the World". Time NewsFeed. Time Inc. Archived from the original on 25 January 2013. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ↑ World Drug Report 2017: Global Overview of Drug Demand and Supply: Latest trends, cross-cutting issues (PDF). United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. May 2017. p. 13. ISBN 978-92-1-148293-5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ↑ "UN commission reclassifies cannabis, yet still considered harmful". UN News. 2 December 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2021.