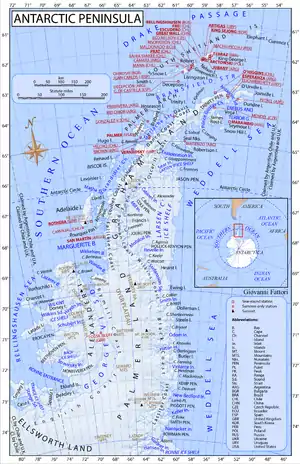

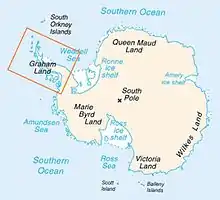

69°30′S 65°00′W / 69.500°S 65.000°W The Antarctic Peninsula, known as O'Higgins Land in Chile and Tierra de San Martín in Argentina, and originally as Graham Land in the United Kingdom and the Palmer Peninsula in the United States, is the northernmost part of mainland Antarctica.

The Antarctic Peninsula is part of the larger peninsula of West Antarctica, protruding 1,300 km (810 miles) from a line between Cape Adams (Weddell Sea) and a point on the mainland south of the Eklund Islands. Beneath the ice sheet that covers it, the Antarctic Peninsula consists of a string of bedrock islands; these are separated by deep channels whose bottoms lie at depths considerably below current sea level. They are joined by a grounded ice sheet. Tierra del Fuego, the southernmost tip of South America, is about 1,000 km (620 miles) away across the Drake Passage.[1]

The Antarctic Peninsula is 522,000 square kilometres (202,000 sq mi) in area and 80% ice-covered.[2]

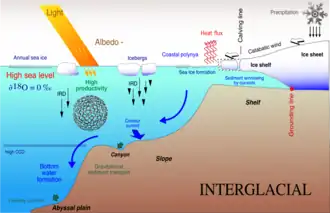

The marine ecosystem around the western continental shelf of the Antarctic Peninsula (WAP) has been subjected to rapid climate change. Over the past 50 years, the warm, moist maritime climate of the northern WAP has shifted south. This climatic change increasingly displaces the once dominant cold, dry continental Antarctic climate. This regional warming has caused multi-level responses in the marine ecosystem such as increased heat transport, decreased sea ice extent and duration, local declines in ice-dependent Adélie penguins, increase in ice-tolerant gentoo and chinstrap penguins, alterations in phytoplankton and zooplankton community composition as well as changes in krill recruitment, abundance and availability to predators.[3][4][5]

The Antarctic Peninsula is currently dotted with numerous research stations, and nations have made multiple claims of sovereignty. The peninsula is part of disputed and overlapping claims by Argentina, Chile, and the United Kingdom. None of these claims have international recognition and, under the Antarctic Treaty System, the respective countries do not attempt to enforce their claims. The British claim, however, is recognised by Australia, France, New Zealand, and Norway. Argentina has the most bases and personnel stationed on the peninsula.

History

%252C_Adelaide_Island%252C_Webb_Island.JPG.webp)

Discovery and naming

The most likely first sighting of the Antarctic Peninsula, and therefore also of the whole Antarctic mainland, was on 27 January 1820 by an expedition of the Imperial Russian Navy led by Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen. But the party did not recognize as the mainland what they thought was an icefield covered by small hillocks.

Three days later, on 30 January 1820, Edward Bransfield and William Smith, with a British expedition, were the first to chart part of the Antarctic Peninsula. This area was later to be called Trinity Peninsula and is the extreme northeast portion of the peninsula. The next confirmed sighting was in 1832 by John Biscoe, a British explorer, who named the northern part of the Antarctic Peninsula as Graham Land.[1][6]

The first European to land on the continent is also disputed. A 19th-century seal hunter, John Davis, was almost certainly the first. But, sealers were secretive about their movements and their logbooks were deliberately unreliable, to protect any new sealing grounds from competition.[1]

Between 1901 and 1904, Otto Nordenskjöld led the Swedish Antarctic Expedition, one of the first expeditions to explore parts of Antarctica. They landed on the Antarctic Peninsula in February 1902, aboard the ship Antarctic, which sank not far from the peninsula. All crew were rescued by an Argentine ship. The British Graham Land expedition between 1934 and 1937 carried out aerial surveys using a de Havilland Fox Moth aircraft, and concluded that Graham Land was not an archipelago but a peninsula.[1][6]

Agreement on the name "Antarctic Peninsula" by the Advisory Committee on Antarctic Names and UK Antarctic Place-Names Committee in 1964 resolved a long-standing difference over the use of the United States' name "Palmer Peninsula" or the British name "Graham Land" for this geographic feature. This dispute was resolved by making Graham Land the part of the Antarctic Peninsula northward of a line between Cape Jeremy and Cape Agassiz; and Palmer Land the part southward of that line, which is roughly 69° S. Palmer Land is named for the United States seal hunter Nathaniel Palmer. The Chilean name for the feature, O'Higgins Land, is in honor of Bernardo O'Higgins, the Chilean patriot and Antarctic visionary. Most other Spanish-speaking countries call it la Península Antártica, though Argentina also officially refers to this as Tierra de San Martín; as of 2018 Argentina has more bases and personnel in the peninsula than any other nation.[1]

Other portions of the peninsula are named by and after the various expeditions that discovered them, including the Bowman, Black, Danco, Davis, English, Fallières, Nordenskjöld, Loubet, and Wilkins Coasts.[1]

Research stations

The first Antarctic research stations were established during World War II by a British military operation, Operation Tabarin.[7]

The 1950s saw a marked increase in the number of research bases as Britain, Chile and Argentina competed to make claims over the same area.[8] Meteorology and geology were the primary research subjects.

Since the peninsula has the mildest climate in Antarctica, the highest concentration of research stations on the continent can be found there, or on the many nearby islands, and it is the part of Antarctica most often visited by tour vessels and yachts. Occupied bases include Base General Bernardo O'Higgins Riquelme, Bellingshausen Station, Carlini Base, Comandante Ferraz Antarctic Station, Palmer Station, Rothera Research Station, and San Martín Base. Today on the Antarctic Peninsula there are many abandoned scientific and military bases. Argentina's Esperanza Base was the birthplace of Emilio Marcos Palma, the first person to be born in Antarctica.[9]

Oil spill

The grounding of the Argentine ship the ARA Bahía Paraíso and subsequent 170,000 US gal (640,000 L; 140,000 imp gal) oil spill occurred near the Antarctic Peninsula in 1989.[10][11][12]

Geology

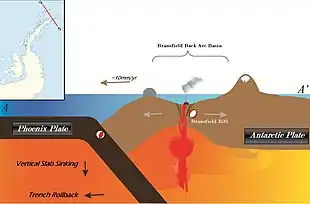

Antarctica was once part of the Gondwana supercontinent. Outcrops from this time include Ordovician and Devonian granites and gneiss found in the Scar Inlet and Joerg Peninsula, while the Carboniferous-Triassic Trinity Peninsula Group are sedimentary rocks that outcrop in Hope Bay and Prince Gustav Channel. Ring of Fire volcanic rocks erupted in the Jurassic, with the breakup of Gondwana, and outcrop in eastern Graham Land as volcanic ash deposits. Volcanism along western Graham Land dates from the Cretaceous to present times, and outcrops are found along the Gerlache Strait, the Lemaire Channel, Argentine Islands, and Adelaide Island. These rocks in western Graham Land include andesite lavas and granite from the magma, and indicate Graham Land was a continuation of the Andes. This line of volcanoes are associated with subduction of the Phoenix Plate. Metamorphism associated with this subduction is evident in the Scotia Metamorphic Complex, which outcrops on Elephant Island, along with Clarence and Smith Islands of the South Shetland Islands. The Drake Passage opened about 30 Ma as Antarctica separated from South America. The South Shetland Island separated from Graham Land about 4 Ma as a volcanic rift formed within the Bransfield Strait. Three dormant submarine volcanoes along this rift include The Axe, Three Sisters, and Orca. Deception Island is an active volcano at the southern end of this rift zone. Notable fossil locations include the Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous Fossil Bluff Group of Alexander Island, Early Cretaceous sediments in Byers Peninsula on Livingston Island, and the sediments on Seymour Island, which include the Cretaceous extinction.[13]

Geography

The peninsula is very mountainous, its highest peaks rising to about 2,800 m (9,200 ft). Notable peaks on the peninsula include Deschanel Peak, Mounts Castro, Coman, Gilbert, Jackson, William, Owen, Scott, and Hope, which is the highest point at 3,239 m (10,627 ft),[14] Mount William, Mount Owen and Mount Scott. These mountains are considered to be a continuation of the Andes of South America, with a submarine spine or ridge connecting the two.[15] This is the basis for the position advanced by Chile and Argentina for their territorial claims. The Scotia Arc is the island arc system that links the mountains of the Antarctic Peninsula to those of Tierra del Fuego.

There are various volcanoes in the islands around the Antarctic Peninsula. This volcanism is related to extensional tectonics in Bransfield Rift to the west and Larsen Rift to the east.[16]

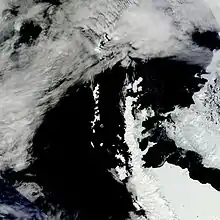

The landscape of the peninsula is typical Antarctic tundra. The peninsula has a sharp elevation gradient, with glaciers flowing into the Larsen Ice Shelf, which experienced significant breakup in 2002. Other ice shelves on the peninsula include the George VI, Wilkins, Wordie and Bach Ice Shelves. The Filchner-Ronne Ice Shelf lies to the east of the peninsula.

Islands along the peninsula are mostly ice-covered and connected to the land by pack ice.[17] Separating the peninsula from nearby islands are the Antarctic Sound, Erebus and Terror Gulf, George VI Sound, Gerlache Strait and the Lemaire Channel. The Lemaire Channel is a popular destination for tourist cruise ships that visit Antarctica. Further to the west lies the Bellingshausen Sea and in the north is the Scotia Sea. The Antarctic Peninsula and Cape Horn create a funneling effect, which channels the winds into the relatively narrow Drake Passage.

Hope Bay, at 63°23′S 057°00′W / 63.383°S 57.000°W, is near the northern extremity of the peninsula, Prime Head, at 63°13′S. Near the tip at Hope Bay is Sheppard Point. The part of the peninsula extending northeastwards from a line connecting Cape Kater to Cape Longing is called the Trinity Peninsula. Brown Bluff is a rare tuya and Sheppard Nunatak is found here also. The Airy, Seller, Fleming and Prospect Glaciers form the Forster Ice Piedmont along the west coast of the peninsula. Charlotte Bay, Hughes Bay and Marguerite Bay are all on the west coast as well.

On the east coast is the Athene Glacier; the Arctowski and Åkerlundh Nunataks are both just off the east coast. A number of smaller peninsulas extend from the main Antarctic Peninsula, including Hollick-Kenyon Peninsula and Prehn Peninsula at the base of the Antarctic Peninsula. Also located here are the Scaife Mountains. The Eternity Range is found in the middle of the peninsula. Other geographical features include Avery Plateau, the twin towers of Una Peaks.

Climate

Because the Antarctic Peninsula, which reaches north of the Antarctic Circle, is the most northerly part of Antarctica, it has the mildest climates within this continent. Its climate is therefore classified as a tundra, rather than an ice cap. Its temperatures are warmest in January, averaging 1 to 2 °C (34 to 36 °F), and coldest in June, averages from −15 to −20 °C (5 to −4 °F). Its west coast from the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula south to 68° S, which has a maritime Antarctic climate, is the mildest part of the Antarctic Peninsula. Within this part of the Antarctic Peninsula, temperatures exceed 0 °C (32 °F) for 3 or 4 months during the summer, and rarely fall below −10 °C (14 °F) during the winter. Farther south along the west coast and the northeast coast of the peninsula, mean monthly temperatures exceed 0 °C (32 °F) for only one or two months of summer and average around −15 °C (5 °F) in winter. The east coast of the Antarctic Peninsula south of 63° S is generally much colder, with mean temperatures exceeding 0 °C (32 °F) for at most one month of summer, and winter mean temperatures ranging from −5 to −25 °C (23 to −13 °F). The colder temperatures of the southeast, Weddell Sea side, of the Antarctic Peninsula are reflected in the persistence of ice shelves that cling to the eastern side.[18][19]

Precipitation varies greatly within the Antarctic Peninsula. From the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula to 68° S, precipitation averages 35–50 cm (14–20 in) per year. A good portion of this precipitation falls as rain during the summer, on two-thirds of the days of the year, and with little seasonal variation in amounts. Between about 68° S and 63° S on the west coast of the Antarctic Peninsula and along its northeast coast, precipitation is 35 cm (14 in) or less with occasional rain. Along the east coast of the Antarctic Peninsula south of 63° S, precipitation ranges from 10 to 15 cm (3.9 to 5.9 in). In comparison, the subantarctic islands have precipitation of 100–200 cm (39–79 in) per year and the dry interior of Antarctica is a virtual desert with only 10 cm (3.9 in) precipitation per year.[19]

Climate change

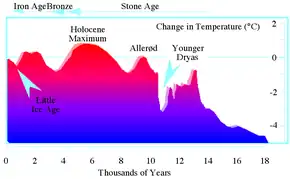

Because of issues concerning global climate change, the Antarctic Peninsula and adjacent parts of the Weddell Sea and its Pacific continental shelf have been the subject of intensive geologic, paleontologic, and paleoclimatic research by interdisciplinary and multinational groups over the last several decades. The combined study of the glaciology of its ice sheet and the paleontology, sedimentology, stratigraphy, structural geology, and volcanology of glacial and nonglacial deposits of the Antarctic Peninsula has allowed the reconstruction of the paleoclimatology and prehistoric ice sheet fluctuation of it for over the last 100 million years. This research shows the dramatic changes in climate, which have occurred within this region after it reached its approximate position within the Antarctic Circle during the Cretaceous Period.[20][21][22][23][24]

The Fossil Bluff Group, which outcrops within Alexander Island, provides a detailed record, which includes paleosols and fossil plants, of Middle Cretaceous (Albian) terrestrial climates. The sediments that form the Fossil Bluff Group accumulated within a volcanic island arc, which now forms the bedrock backbone of the Antarctic Peninsula, in prehistoric floodplains and deltas and offshore as submarine fans and other marine sediments. As reflected in the plant fossils, paleosols, and climate models, the climate was warm, humid, and seasonally dry. According to climate models, the summers were dry and winters were wet. The rivers were perennial and subject to intermittent flooding as the result of heavy rainfall.[22][25]

Warm high-latitude climates reached a peak during the mid-Late Cretaceous Cretaceous Thermal Maximum. Plant fossils found within the Late Cretaceous (Coniacian and Santonian-early Campanian) strata of the Hidden Lake and Santa Maria formations, which outcrop within James Ross, Seymour, and adjacent islands, indicate that this emergent volcanic island arc enjoyed warm temperate or subtropical climates with adequate moisture for growth and without extended periods of below freezing winter temperatures.[22][26]

After the peak warmth of the Cretaceous thermal maximum the climate, both regionally and globally, appears to have cooled as seen in the Antarctic fossil wood record. Later, warm high-latitude climates returned to the Antarctic Peninsula region during the Paleocene and early Eocene as reflected in fossil plants. Abundant plant and marine fossils from Paleogene marine sediments that outcrop on Seymour Island indicate the presence of cool and moist, high-latitudes environment during the early Eocene.[20][22]

Detailed studies of the paleontology, sedimentology, and stratigraphy of glacial and nonglacial deposits within the Antarctic Peninsula and adjacent parts of the Weddell Sea and its Pacific continental shelf have found that it has become progressively glaciated as the climate of Antarctica dramatically and progressively cooled during the last 37 million years. This progressive cooling was contemporaneous with a reduction in atmospheric CO2 concentrations. During this climatic cooling, the Antarctic Peninsula was probably the last region of Antarctica to have been fully glaciated. Within the Antarctic Peninsula, mountain glaciation was initiated during the latest Eocene, about 37–34 Ma. The transition from temperate, alpine glaciation to a dynamic ice sheet occurred about 12.8 Ma. At this time, the Antarctic Peninsula formed as the bedrock islands underlying it were overridden and joined by an ice sheet in the early Pliocene about 5.3–3.6 Ma. During the Quaternary period, the size of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet has fluctuated in response to glacial–interglacial cycles. During glacial epochs, this ice sheet was significantly thicker than it is currently and extended to the edge of the continental shelves. During interglacial epochs, the West Antarctica Ice Sheet was thinner than during glacial epochs and its margins lay significantly inland of the continental margins.[20][21][22]

During the Last Glacial Maximum, about 20,000 to 18,000 years ago, the ice sheet covering the Antarctic Peninsula was significantly thicker than it is now. Except for a few isolated nunataks, the Antarctic Peninsula and its associated islands were completely buried by the ice sheet. In addition, the ice sheet extended past the present shoreline onto the Pacific outer continental shelf and completely filled the Weddell Sea up to the continental margin with grounded ice.[20][23][24][27]

The deglaciation of the Antarctic Peninsula largely occurred between 18,000 and 6,000 years ago as an interglacial climate was established in the region. It initially started about 18,000 to 14,000 years ago with retreat of the ice sheet from the Pacific outer continental shelf and the continental margin within the Weddell Sea. Within the Weddell Sea, the transition from grounded ice to a floating ice shelf occurred about 10,000 years ago. The deglaciation of some locations within the Antarctic Peninsula continued until 4,000 to 3,000 years ago. Within the Antarctic Peninsula, an interglacial climatic optimum occurred about 3,000 to 5,000 years ago. After the climate optimum, a distinct climate cooling, which lasted until historic times, occurred.[23][24][27][28]

The Antarctic Peninsula is a part of the world that is experiencing extraordinary warming.[29] Each decade for the last five, average temperatures in the Antarctic Peninsula have risen by 0.5 °C (0.90 °F).[30] Ice mass loss on the peninsula occurred at a rate of 60 billion tons / year in 2006,[31] with the greatest change occurring in the northern tip of the peninsula.[32] Seven ice shelves along the Antarctic Peninsula have retreated or disintegrated in the last two decades.[29] Research by the United States Geological Survey has revealed that every ice front on the southern half of the peninsula experienced a retreat between 1947 and 2009.[33] According to a study by the British Antarctic Survey, glaciers on the peninsula are not only retreating but also increasing their flow rate as a result of increased buoyancy in the lower parts of the glaciers.[34] Professor David Vaughan has described the disintegration of the Wilkins Ice Shelf as the latest evidence of rapid warming in the area.[35] The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has been unable to determine the greatest potential effect on sea level rise that glaciers in the region may cause.[34]

Flora and fauna

The coasts of the peninsula have the mildest climate in Antarctica and moss and lichen-covered rocks are free of snow during the summer months, although the weather is still intensely cold and the growing season very short. The plant life today is mainly mosses, lichens and algae adapted to this harsh environment, with lichens preferring the wetter areas of the rocky landscape. The most common lichens are Usnea and Bryoria species. Antarctica's two flowering plant species, the Antarctic hair grass (Deschampsia antarctica) and Antarctic pearlwort (Colobanthus quitensis) are found on the northern and western parts of the Antarctic Peninsula, including offshore islands, where the climate is relatively mild. Lagotellerie Island in Marguerite Bay is an example of this habitat.[18][19][36]

Xanthoria elegans and Caloplaca are visible crustose lichens seen on coastal rocks.[37]

Antarctic krill are found in the seas surrounding the peninsula and the rest of the continent. The crabeater seal spends most of its life in the same waters feeding on krill. Bald notothen is a cryopelagic fish that lives in sub-zero water temperatures around the peninsula. Vocalizations of the sei whale can be heard emanating from the waters surrounding the Antarctic Peninsula.[18]

Whales include the Antarctic minke whale, dwarf minke whale, and the killer whale.[37]

The animals of Antarctica live on food they find in the sea—not on land—and include seabirds, seals and penguins. The seals include: leopard seal (Hydrurga leptonyx), Weddell seal (Leptonychotes weddellii), the huge southern elephant seal (Mirounga leonina), and crabeater seal (Lobodon carcinophagus).[18]

Penguin species found on the peninsula, especially near the tip and surrounding islands, include the chinstrap penguin, emperor penguin, gentoo penguin and the Adélie penguin. Petermann Island is the world's southernmost colony of gentoo penguins. The exposed rocks on the island is one of many locations on the peninsula that provides a good habitat for rookeries. The penguins return each year and may reach populations of more than ten thousand. Of these the most common on the Antarctic Peninsula are the chinstrap and gentoo, with the only breeding colony of emperor penguins in West Antarctica an isolated population on the Dion Islands, in Marguerite Bay on the west coast of the peninsula. Most emperor penguins breed in East Antarctica.[18][19][36]

Seabirds of the Southern Ocean and West Antarctica found on the peninsula include: southern fulmar (Fulmarus glacialoides), the scavenging southern giant petrel (Macronectes giganteus), Cape petrel (Daption capense), snow petrel (Pagodroma nivea), the small Wilson's storm-petrel (Oceanites oceanicus), imperial shag (Phalacrocorax atriceps), snowy sheathbill (Chionis alba), the large south polar skua (Catharacta maccormicki), brown skua (Catharacta lönnbergi), kelp gull (Larus dominicanus), and Antarctic tern (Sterna vittata). The imperial shag is a cormorant which is native to many sub-Antarctic islands, the Antarctic Peninsula and southern South America.[18][19]

Also present are the Antarctic petrel, Antarctic shag, king penguin, macaroni penguin, and Arctic tern.[37]

Threats and preservation

Although this very remote part of the world has never been inhabited and is protected by the Antarctic Treaty System, which bans industrial development, waste disposal and nuclear testing, there is still a threat to these fragile ecosystems from increasing tourism, primarily on cruises across the Southern Ocean from the port of Ushuaia, Argentina.

Paleoflora and paleofauna

A rich record of fossil leaves, wood, pollen, and flowers demonstrates that flowering plants thrived in subtropical climates within the volcanic island arcs that occupied the Antarctic Peninsula region during the Cretaceous and very early Paleogene periods. The analysis of fossil leaves and flowers indicates that semitropical woodlands, which were composed of ancestors of plants that live in the tropics today, thrived within this region during a global thermal maximum with summer temperatures that averaged 20 °C (68 °F).

The oldest fossil plants come from the middle Cretaceous (Albian) Fossil Bluff Group, which outcrop along the edge of Alexander Island. These fossils reveal that at this time the forests consisted of large conifers, with mosses and ferns in the undergrowth. The paleosols, in which trees are rooted, have physical characteristics indicative of modern soils that form under seasonally dry climates with periodic high rainfall.[25] Younger Cretaceous strata, which outcrop within James Ross, Seymour, and adjacent islands, contain fossil plants of Late Cretaceous angiosperms with leaf morphotypes that are similar to those of living families such as Sterculiaceae, Lauraceae, Winteraceae, Cunoniaceae, and Myrtaceae. They indicate that the emergent parts of the volcanic island arc, the eroded roots of which now form the central part of the Antarctic Peninsula, were covered by either warm temperate or subtropical forests.[26]

These fossil plants are indicative of tropical and subtropical forest at high paleolatitudes during the Middle and Late Cretaceous, which grew in climates without extended periods of below freezing winter temperatures and with adequate moisture for growth.[22] The Cretaceous strata of James Ross Island also yielded the dinosaur genus Antarctopelta, which was the first dinosaur fossil to be found on Antarctica.[38]

Paleogene and Early Eocene marine sediments that outcrop on Seymour Island contain plant-rich horizons. The fossil plants are dominated by permineralized branches of conifers and compressions of angiosperm leaves, and are found within carbonate concretions. These Seymour Island region fossils date to about 51.5–49.5 Ma and are dominated by leaves, cone scales, and leafy branches of Araucarian conifers, very similar in all respects to living Araucaria araucana (monkey puzzle) from Chile. They suggest that the adjacent parts of the prehistoric Antarctic Peninsula were covered by forests that grew in a cool and moist, high-latitude environment during the early Eocene.[22]

During the Cenozoic climatic cooling, the Antarctic Peninsula was the last region of Antarctica to have been fully glaciated according to current research. As a result, this region was probably the last refugium for plants and animals that had inhabited Antarctica after it separated from the Gondwanaland supercontinent.

Analysis of paleontologic, stratigraphic, and sedimentologic data acquired from the study of drill core and seismic acquired during the Shallow Drilling on the Antarctic Continental Shelf (SHALDRIL) and other projects and from fossil collections from and rock outcrops within Alexander, James Ross, King George, Seymour, and South Shetland Islands has yielded a record of the changes in terrestrial vegetation that occurred within the Antarctic Peninsula over the course of the past 37 million years.[21][22]

This research found that vegetation within the Antarctic Peninsula changed in response to a progressive climatic cooling that started with the initiation of mountain glaciation in the latest Eocene, about 37–34 Ma. The cooling was contemporaneous with glaciation elsewhere in Antarctica and a reduction in atmospheric CO2 concentrations. Initially, during the Eocene, this climate cooling resulted in a decrease in diversity of the angiosperm-dominated vegetation that inhabited the northern Antarctic Peninsula. During the Oligocene, about 34–23 Ma, these woodlands were replaced by a mosaic of southern beech (Nothofagus) and conifer-dominated woodlands and tundra as the climate continued to cool. By middle Miocene, 16–11.6 Ma, a tundra landscape completely replaced any remaining woodlands. At this time, woodlands became completely extirpated from the Antarctic Peninsula and all of Antarctica. A tundra landscape probably persisted until about 12.8 Ma when the transition from a temperate, alpine glaciation to a dynamic ice sheet occurred. Eventually, the Antarctic Peninsula was overridden by an ice sheet, which has persisted without any interruption to this day, in the early Pliocene, about 5.3–3.6 Ma.[21][22]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Stewart, J. (2011). Antarctic: An Encyclopedia. New York, NY: McFarland & Co. ISBN 978-0-7864-3590-6.

- ↑ Antarctic Peninsula Ice Sheet

- ↑ Ducklow, Hugh W; Baker, Karen; Martinson, Douglas G; Quetin, Langdon B; Ross, Robin M; Smith, Raymond C; Stammerjohn, Sharon E; Vernet, Maria; Fraser, William (2007-01-29). "Marine pelagic ecosystems: the West Antarctic Peninsula". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 362 (1477): 67–94. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1955. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 1764834. PMID 17405208.

- ↑ Schofield, O.; Ducklow, H. W.; Martinson, D. G.; Meredith, M. P.; Moline, M. A.; Fraser, W. R. (2010-06-18). "How Do Polar Marine Ecosystems Respond to Rapid Climate Change?". Science. 328 (5985): 1520–1523. Bibcode:2010Sci...328.1520S. doi:10.1126/science.1185779. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 20558708. S2CID 43782473.

- ↑ Montes-Hugo, M.; Doney, S. C.; Ducklow, H. W.; Fraser, W.; Martinson, D.; Stammerjohn, S. E.; Schofield, O. (2009-03-13). "Recent Changes in Phytoplankton Communities Associated with Rapid Regional Climate Change Along the Western Antarctic Peninsula". Science. 323 (5920): 1470–1473. Bibcode:2009Sci...323.1470M. doi:10.1126/science.1164533. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 19286554. S2CID 9723605.

- 1 2 Scott, Keith (1993). The Australian Geographic book of Antarctica. Terrey Hills, NSW: Australian Geographic. pp. 114–118. ISBN 978-1-86276-010-3.

- ↑ "British Research Stations and Refuges - History". British Antarctic Survey. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- ↑ Thomson, Michael; Swithinbank, Charles (1 August 1985). "The prospects for Antarctic Minerals". New Scientist (1467): 31–35.

- ↑ Simon Romero (6 January 2016). "Antarctic Life: No Dogs, Few Vegetables and 'a Little Intense' in the Winter". New York Times.

- ↑ "The world's frozen clean room". Business Week. 22 January 1990.

- ↑ Smith, James F. (5 April 1990). "Struggling to Protect 'The Ice'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2011-01-30.

- ↑ Sweet, Stephen T.; Kennicutt, Mahlon C.; Klein, Andrew G. (2015-02-20). "The Grounding of theBahía Paraíso, Arthur Harbor, Antarctica". Handbook of Oil Spill Science and Technology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 547–556. doi:10.1002/9781118989982.ch23. ISBN 978-1-118-98998-2.

- ↑ Leat, Philip; Francis, Jane (2019). Fox, Adrian (ed.). Geology of Graham Land, in Antarctic Peninsula: A Visitor's Guide. London: Natural History Museum. pp. 18–31. ISBN 9780565094652.

- ↑ New satellite imagery reveals new highest Antarctic Peninsula Mountain British Antarctic Survey, 11 December 2017

- ↑ "Operation IceBridge Returns to Antarctica". NASA Earth Observatory. NASA. October 15, 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ↑ Kraus, Stefan; Kurbatov, Andrei; Yates, Martin (2013). "Geochemical signatures of tephras from Quaternary Antarctic Peninsula volcanoes". Andean Geology. 40 (1): 1–40. doi:10.5027/andgeoV40n1-a01.

- ↑ Tulloch, Coral (2003). Antarctica: Heart of the World. Sydney: ABC Books. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-7333-0912-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Moss, S. (1988). Natural History of The Antarctic Peninsula. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-06269-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Draggan, S. & World Wildlife Fund (2009). Cleveland, C. J. (ed.). "Antarctic Peninsula". Encyclopedia of Earth. Washington, DC: National Council for Science and the Environment.

- 1 2 3 4 Anderson, J. B. (1999). Antarctic Marine Geology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-59317-5.

- 1 2 3 4 Anderson, J. B.; Warny, S.; Askin, R. A.; Wellner, J. S.; Bohaty, S. M.; Kirshner, A. E.; Livsey, D. N.; Simms, A. R.; Smith, Tyler R.; Ehrmann, W.; Lawverh, L. A.; Barbeaui, D.; Wise, S. W.; Kulhanek, D. K.; Weaver, F. M.; Majewski, W. (2012). "Progressive Cenozoic cooling and the demise of Antarctica's last refugium". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (28): 11356–11360. doi:10.1073/pnas.1014885108. PMC 3136253. PMID 21709269.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Francis, J. E.; Ashworth, A.; Cantrill, D. J.; Crame, J. A.; Howe, J.; Stephens, R.; Tosolini, A.-M.; Thorn, V. (2008). "100 Million Years of Antarctic Climate Evolution: Evidence from Fossil Plants". In Cooper, A. K.; Barrett, P. J.; Stagg, H.; Storey, B.; Stump, E.; Wise, W.; et al. (eds.). Antarctica: A Keystone in a Changing World. Proceedings of the 10th International Symposium on Antarctic Earth Sciences. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. pp. 19–27. ISBN 9780309118545.

- 1 2 3 Heroy, D. C.; Anderson, J. B. (2005). "Ice-sheet extent of the Antarctic Peninsula region during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) — insights from glacial geomorphology". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 117 (11): 1497–1512. Bibcode:2005GSAB..117.1497H. doi:10.1130/b25694.1.

- 1 2 3 Ingolfsson, O.; Hjort, C.; Humlum, O. (2003). "Glacial and Climate History of the Antarctic Peninsula since the Last Glacial Maximum". Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research. 35 (2): 175–186. doi:10.1657/1523-0430(2003)035[0175:gachot]2.0.co;2. S2CID 55371952.

- 1 2 Falcon-Lang, H. J.; Cantrill, D. J.; Nichols, G. J. (2001). "Biodiversity and terrestrial ecology of a mid-Cretaceous, high-latitude floodplain, Alexander Island, Antarctica". Journal of the Geological Society of London. 158 (4): 709–724. Bibcode:2001JGSoc.158..709F. doi:10.1144/jgs.158.4.709. S2CID 129448125.

- 1 2 Hayes, P. A.; Francis, J. E.; Cantrill, D. J. (2006). "Palaeoclimate of Late Cretaceous Angiosperm leaf floras, James Ross Island, Antarctic". In Francis, J. E.; Pirrie, D.; Crame, J. A. (eds.). Cretaceous-Tertiary High Latitude Palaeoenvironments, James Ross Basin. Special Publication 258. Geological Society of London. pp. 49–62. ISBN 9781862391970.

- 1 2 Livingstone, S. J.; Cofaigh, C. O.; Stokes, C. R.; Hillenbrand, C.-D.; Vieli, A.; Jamieson, S. S. R. (2011). "Antarctic palaeo-ice streams" (PDF). Earth-Science Reviews (published 2011-10-25). 111 (1–2): 90–128. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2011.10.003. S2CID 129048010.

- ↑ Johnson, J. S.; Bentley, M. J.; Roberts, S. J.; Binnie, S. A.; Freeman, S. P. H. T. (2011). "Holocene deglacial history of the northeast Antarctic Peninsula — A review and new chronological constraints". Quaternary Science Reviews. 30 (27–28): 3791–3802. Bibcode:2011QSRv...30.3791J. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2011.10.011.

- 1 2 "Even The Antarctic Winter Cannot Protect Wilkins Ice Shelf". Science Daily. 2008-06-14. Archived from the original on 2008-06-17. Retrieved 2008-06-18.

- ↑ "Satellites Shed Light On Global Warming". TerraDaily.com. 29 April 2007. Retrieved 2011-01-30.

- ↑ "Antarctic Ice Loss". TerraDaily.com. 14 January 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-29.

- ↑ "Antarctic Heating and Cooling Trends". Goddard Space Flight Center. NASA. 12 July 2005. Retrieved 2008-03-29.

- ↑ Ferrigno, J. G.; Cook, A. J.; Mathie, A. M.; Williams, R. S. Jr.; Swithinbank, C.; Foley, K. M.; Fox, A. J.; Thomson, J. W.; Sievers, J. (2009). Coastal-Change and Glaciological Map of the Palmer Land Area, Antarctica: 1947–2009. Geologic Investigations Series Map no. I-2600-C. Reston, VA: United States Geological Survey.

- 1 2 "Hundreds Of Antarctic Peninsula Glaciers Accelerating As Climate Warms". Science Daily. 2007-06-06. Archived from the original on 2008-07-05. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

- ↑ "Wilkins Ice Shelf hanging by its last thread". European Space Agency. 2008-07-10. Archived from the original on 2008-08-08. Retrieved 2008-08-08.

- 1 2 Hogan, C. M.; Draggan, S.; World Wildlife Fund (2011). Cleveland, C. J. (ed.). "Marielandia Antarctic tundra". Encyclopedia of Earth. Washington, DC: National Council for Science and the Environment.

- 1 2 3 Lowen, James (2011). Antarctic Wildlife: A Visitor's Guide. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 50–51, 160–231. ISBN 9780691150338.

- ↑ Salgado, L.; Gasparini, Z. (2006). "Reappraisal of an ankylosaurian dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous of James Ross Island (Antarctica)". Geodiversitas. 28 (11): 119–135.

External links

- "Of Ice and Men" Account of a tourist visit to the Antarctic Peninsula by Roderick Eime

- Biodiversity at Ardley Island, South Shetland archipelago, Antarctic Peninsula

- 89 photos of the Antarctic Peninsula

.svg.png.webp)