Multiple governments have set up permanent research stations in Antarctica and these bases are widely distributed. Unlike the drifting ice stations set up in the Arctic, the research stations of the Antarctic are constructed either on rocks or on ice that are (for practical purposes) fixed in place.

Many of the stations are staffed throughout the year. Of the 56 signatories to the Antarctic Treaty, a total of 55 countries (as of 2023)[1] operate seasonal (summer) and year-round research stations on the continent. The number of people performing and supporting scientific research on the continent and nearby islands varies from approximately 4,800 during the summer to around 1,200 during the winter (June).[2] In addition to these permanent stations, approximately 30 field camps are established each summer to support specific projects.[3]

History

First bases

During the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration in the late 19th century, the first bases on the continent were established. In 1898, Carsten Borchgrevink, a Norwegian/British explorer, led the British Antarctic Expedition to Cape Adare, where he established the first Antarctic base on Ridley Beach. This expedition is often referred to now as the Southern Cross Expedition, after the expedition's ship name. Most of the staff were Norwegian, but the funds for the expedition were British, provided by Sir George Newnes. The 10 members of the expedition explored Robertson Bay to the west of Cape Adare by dog teams, and later, after being picked up by the ship at the base, went ashore on the Ross Ice Shelf for brief journeys. The expedition hut is still in good condition and visited frequently by tourists.

The hut was later occupied by Scott's Northern Party under the command of Victor Campbell for a year in 1911, after its attempt to explore the eastern end of the ice shelf discovered Roald Amundsen already ashore preparing for his assault on the South Pole.

In 1903, Dr William S. Bruce's Scottish National Antarctic Expedition set off to Antarctica, with one of its aims to establish a meteorological station in the area. After the expedition failed to find land, Bruce decided to head back to the Laurie Island in the South Orkneys and find an anchorage there.[4] The islands were well-situated as a site for a meteorological station, and their relative proximity to the South American mainland allowed a permanent station to be established.[5] Bruce instituted a comprehensive programme of work, involving meteorological readings, trawling for marine samples, botanical excursions, and the collection of biological and geological specimens.[4]

The major task completed during this time was the construction of a stone building, christened "Omond House".[6] This was to act as living accommodation for the parties that would remain on Laurie Island to operate the proposed meteorological laboratory. The building was constructed from local materials using the dry stone method, with a roof improvised from wood and canvas sheeting. The completed house was 20 feet by 20 feet square (6m × 6m), with two windows, fitted as quarters for six people. Rudmose Brown wrote: "Considering that we had no mortar and no masons' tools it is a wonderfully fine house and very lasting. I should think it will be standing a century hence ..."[7]

The percentage of the summer Antarctic population (formed by Antarctic and Subantarctic research stations) each country makes up:

Bruce later offered to Argentina the transfer of the station and instruments on the condition that the government committed itself to the continuation of the scientific mission.[8] Bruce informed the British officer William Haggard of his intentions in December 1903, and Haggard ratified the terms of Bruce's proposition.[9]

The Scotia sailed back for Laurie Island on 14 January 1904 carrying on board Argentinean officials from the Ministry of Agriculture, National Meteorological Office, Ministry of Livestock and National Postal and Telegraphs Office. In 1906, Argentina communicated to the international community the establishment of a permanent base on the South Orkney Islands.

WWII and postwar expansion

Little happened for the following forty years until the Second World War, when the British launched Operation Tabarin in 1943, to establish a presence on the continent. The chief reason was to establish solid British claims to various uninhabited islands and parts of Antarctica, reinforced by Argentine sympathies toward Germany.

Prior to the start of the war, German aircraft had dropped markers with swastikas across Queen Maud Land in an attempt to create a territorial claim (New Swabia).[10] Led by Lieutenant James Marr, the 14-strong team left the Falkland Islands in two ships, HMS William Scoresby (a minesweeping trawler) and HMS Fitzroy, on Saturday January 29, 1944. Marr had accompanied the British explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton on his final Antarctic expedition in 1921–22.

Bases were established during February near the abandoned Norwegian whaling station on Deception Island, where the Union Flag was hoisted in place of Argentine flags, and at Port Lockroy (on February 11) on the coast of Graham Land. A further base was founded at Hope Bay on February 13, 1945, after a failed attempt to unload stores on February 7, 1944. These bases were the first ever to be constructed on the mainland Antarctica.[11]

The United States starting under the leadership of Admiral Richard E. Byrd constructed a series of five bases near the Bay of Whales named Little America between 1929 and 1958. All of them have now drifted off to sea on icebergs.

A massive expansion in international activity followed the war. Chile organized its First Chilean Antarctic Expedition in 1947–48. Among other accomplishments, it brought the Chilean president Gabriel González Videla to personally inaugurate one of its bases, thereby becoming the first head of state to set foot on the continent.[12] Signy Research Station (UK) was established in 1947, Australia's Mawson Station in 1954, Dumont d'Urville Station was the first French station in 1956. In that same year, the United States built McMurdo Station and Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station, and the Soviet Union built Mirny Station.

In 2023 a research report from an Australian team found that the pollution left by international research stations were at par with some of the busiest ports in the world.

The Antarctic Treaty

The Antarctic Treaty, first signed on 1 December 1959 by 12 countries, stated that scientific investigations in research stations in Antarctica can continue, but all observations must be shared.[13] The Antarctic Treaty also stated that Antarctica can only be used for peaceful purposes and any exploitation of the continent such as mining is forbidden, thus scientific research is the only activity that may be performed on Antarctica.[14] As more countries established research stations on Antarctica, the number of signatories of the treaty increased, with 56 signatories as of 2023, 55 of whom utilize their rights and operate research stations in Antarctica.[13] 7 of the signatories also laid claims on Antarctica (and 4 reserved their rights to do so), with the intention of expanding research in those territories in the future. However, research facilities have also been established by countries in the claimed area of other countries.

Permanent active stations

The United States maintains the southernmost base, Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station, and the largest base and research station in Antarctica, McMurdo Station. The second-southernmost base is the Chinese Kunlun Station at 80°25′2″S during the summer season, and the Russian Vostok Station at 78°27′50″S during the winter season.

Subantarctic stations

Summer-only active stations

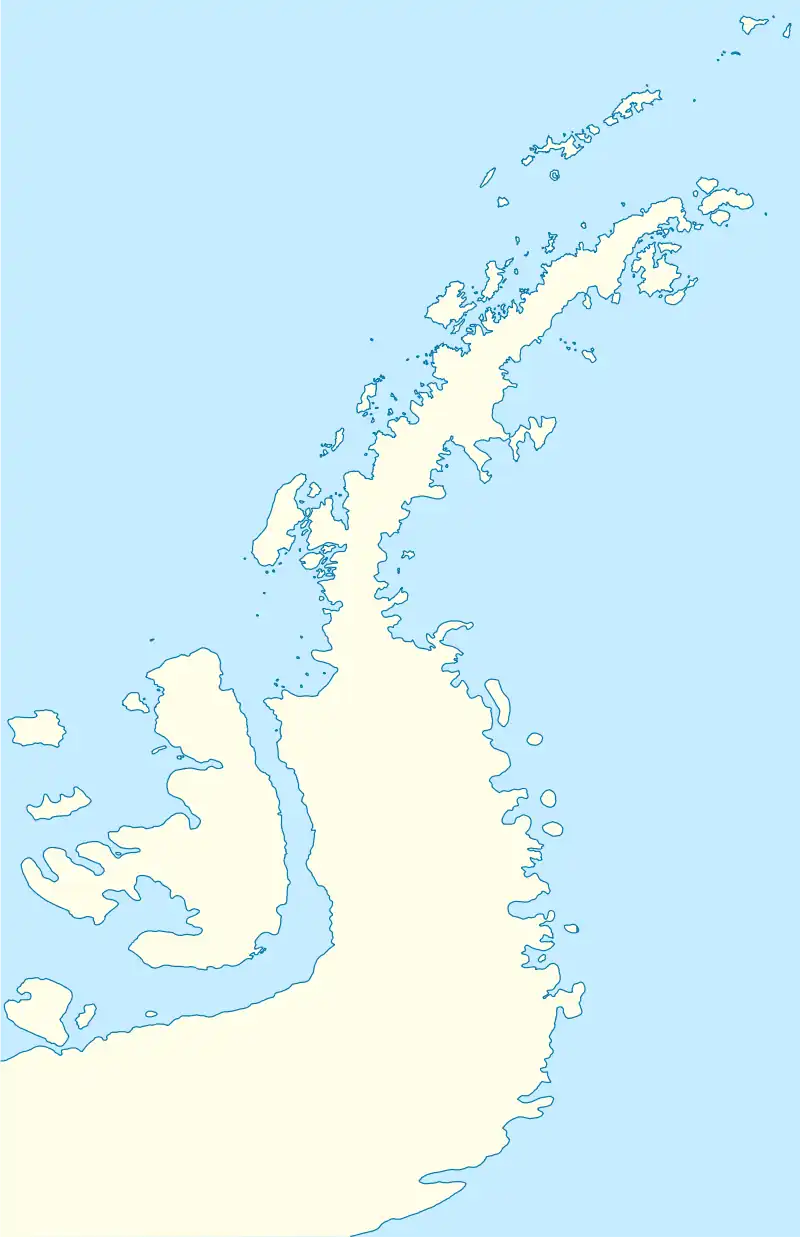

Maps of active stations

Chile

South Africa

India

↑

Inactive stations

See also

Notes

References

- ↑ "01. Antarctic Treaty, done at Washington December 1, 1959". United States Department of State. Retrieved 2023-10-24.

- ↑ Silja Vöneky; Sange Addison-Agyei (May 2011). "Oxford Public International Law". Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law.

- ↑ "4.0 Antarctica - Past and Present". Archived from the original on 2020-01-18. Retrieved 2018-04-06.

- 1 2 Rudmose Brown, R. N.; Pirie, J. H.; Mossman, R. C. (2002). The Voyage of the Scotia. Edinburgh: Mercat Press. pp. 34–57. ISBN 1-84183-044-5.

- ↑ Rudmose Brown, Pirie & Mossman 2002, p. 57.

- ↑ "Voyage of the Scotia 1902–04: The Antarctic". Glasgow Digital Library. Archived from the original on 2008-03-11. Retrieved 2008-06-30.

- ↑ Speak, Peter (2003). William Speirs Bruce: Polar Explorer and Scottish Nationalist. Edinburgh: NMS Publishing. p. 85. ISBN 1-901663-71-X.

- ↑ Escude, Carlos; Cisneros, Andres. "Historia General de las Relaciones Exteriores de la Republica Argentina" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on May 4, 2012. Retrieved July 6, 2012.

- ↑ Moneta, Jose Manuel (1954). Cuatro Años en las Orcadas del Sur (9th ed.). Ediciones Peuser.

- ↑ "HMS Carnarvon Castle 1943". Archived from the original on 2015-07-06. Retrieved 2014-03-05.

- ↑ "Spirit of Scott 2012: Britain's polar interests lie under a cloud". The Daily Telegraph. 27 November 2012. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12.

- ↑ Antarctica and the Arctic: the complete encyclopedia, Volume 1, by David McGonigal, Lynn Woodworth, page 98

- 1 2 "The Antarctic Treaty | Antarctic Treaty". www.ats.aq. Retrieved 2023-10-24.

- ↑ "Mineral resources". Discovering Antarctica. Retrieved 2023-10-24.

- ↑ "New Zealand". Antarctic Treaty. Archived from the original on 5 March 2014. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ↑ "Halley VI Antarctic Research Station". Archello.com. Archived from the original on 2014-01-16. Retrieved 2014-01-16.

- ↑ "Rothera Station R". British Antarctic Survey. Archived from the original on 16 November 2016. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- ↑ "Bird Island Station BI". British Antarctic Survey. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- ↑ "King Edward Pont Station M". British Antarctic Survey. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- ↑ "La Antartida". Archived from the original on 2014-05-12. Retrieved 2014-05-11.

- ↑ "Port Lockroy Diaries". United Kingdom Antarctic Heritage Trust. Archived from the original on 20 December 2018. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- ↑ "History of Port Lockroy (Station A)". British Antarctic Survey. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ↑ "Signy Station H". British Antarctic Survey. Archived from the original on 23 June 2016. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- ↑ "中国正式建成南极泰山科考站". 8 February 2014. Archived from the original on 2014-02-10. Retrieved 2014-02-10.

- ↑ Varetto, Gianni (August 24, 2017). "Belarusian Antarctic Research Vechernyaya Station (WAP BLR-New)". Worldwide Antarctic Program. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ↑ "Current Local Time in Mario Zucchelli Station, Antarctica". timeanddate.com. Archived from the original on 28 April 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ↑ "Dumont d'Urville". Institute Polaire Français. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ↑ Dubrovin, L.I.; Petrov, V.N. (1971). Scientific Stations in Antarctica 1882-1963 [Nauchnye Stanstii V Antarktike 1882-1963] (PDF). Gidrometeorologicheskoe Izdatel'stvo. New Delhi: Indian National Scientific Documentation Center. pp. 327–329. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-01-12. Retrieved 2021-05-28.

- ↑ "History of Faraday (Station F)". British Antarctic Survey. Archived from the original on 23 June 2016. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ↑ Varetto, Gianni (2017). "Giacomo Bove Station". Worldwide Antarctic Program. Archived from the original on 8 October 2018. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- ↑ Joint Standing Committee on the National Capital and External Territories; The Embassy of the Russian Federation. "Submission 21". Parliament of Australia. Archived from the original on 9 June 2022. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- ↑ "French Polar Team - R1 Russkaya Station / Antarctica". Archived from the original on 2017-08-28. Retrieved 2011-10-04.

- ↑ "Deception Island Station B". British Antarctic Survey. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ↑ "Sandefjord Bay Station C". British Antarctic Survey. Archived from the original on 7 October 2018. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ↑ "Hope Bay Station D". British Antarctic Survey. Archived from the original on 16 November 2016. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ↑ "Stonington Island Station E". British Antarctic Survey. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ↑ "Admiralty Bay Station G". British Antarctic Survey. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ↑ "Prospect Point Station J". British Antarctic Survey. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ↑ "Anvers Island Station N". British Antarctic Survey. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ↑ "Danco Island Station O". British Antarctic Survey. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ↑ "Livingstone Island Station P". British Antarctic Survey. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ↑ "Adelaide Station T". British Antarctic Survey. Archived from the original on 16 November 2016. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ↑ "View Point Station V". British Antarctic Survey. Archived from the original on 7 October 2018. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ↑ "Detaille Island Station W". British Antarctic Survey. Archived from the original on 7 October 2018. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ↑ "Horseshoe Island Station Y". British Antarctic Survey. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

External links

- Antarctic Station Catalogue (PDF) (catalogue). Council of Managers of National Antarctic Programs. August 2017. ISBN 978-0-473-40409-3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 October 2022. Retrieved 16 January 2023.

- Research stations

- COMNAP Antarctic Facilities, 2014, Excel file

- COMNAP Antarctic Facilities Map, 2009 (Archived September 15, 2009, at the Wayback Machine)

- Antarctic Exploration Timeline, animated map of Antarctic exploration and settlement, showing where and when Antarctic research stations were established

- Antarctic Digital Database Map Viewer SCAR

.svg.png.webp)