Ashville, Ohio | |

|---|---|

Looking North on Long Street | |

Location of Ashville, Ohio | |

Location of Ashville in Pickaway County | |

Ashville  Ashville  Ashville | |

| Coordinates: 39°43′3″N 82°57′10″W / 39.71750°N 82.95278°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Ohio |

| County | Pickaway |

| Township | Harrison |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Steve Welsh |

| • Village Administrator | Franklin Christman |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2.23 sq mi (5.78 km2) |

| • Land | 2.23 sq mi (5.78 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 715 ft (238 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 4,529 |

| • Density | 2,030.03/sq mi (783.88/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 43103 |

| Area code(s) | 740, 220 |

| FIPS code | 39-02680[3] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1064348[2] |

| Website | http://ashvilleohio.gov |

Ashville is a village in Pickaway County, Ohio, United States. The population was 4,621 at the 2020 census. Ashville is located 17 miles south of Columbus and 8 miles north of Circleville.

History

Long before the American settlement of Ohio, Hopewell Native Americans inhabited the lands that became Ashville. The Snake Den Mounds were constructed a few miles outside of the present day village and were believed to have been built prior to C.E. 500. The site was examined in the late 1890s by Warren K. Moorehead, where he found artifacts of the ancient civilization and skeletal remains.[4]

Centuries later the primary inhabitants were the Pekowi band of the Shawnee. This band of natives was the name sake for Pickaway County.[5] The Pekowi people lived in the area for much of the 18th Century, but eventually left as America pushed westward.[6]

Early American settlement

Ashville sits on land that had been acquired by Great Britain in 1763, following the defeat of France in the French and Indian War, but was prohibited to be settled by white settlers. When the United States claimed the region following the American Revolutionary War, the area became part of the Congress Lands East of Scioto River and was first surveyed in 1799 as part of the Scioto River Base Surveys.[7]

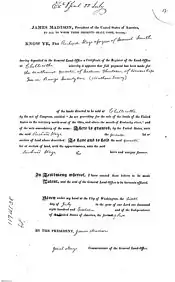

Richard Staige (or Stage) Sr., born in Edinburgh, first settled the land that would become Ashville in 1808, after migrating from Virginia. Following his death in 1811, his sons Richard Jr. and William would each build a distillery on the family's land, opening them the following year. Richard Jr. bought the 77.57 acres they inhabited from the Chillicothe Land Office on July 6, 1816.[8]

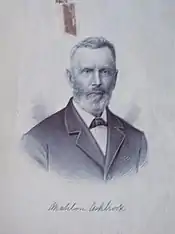

In 1837, Richard Jr. sold his distillery to Mahlon Ashbrook. By 1845, Ashbrook had also built a gristmill on Walnut Creek and owned a large store that was run by his sister Iva "Ivy" and her husband Daniel Kellerman, who went on to be the first postmaster of the town, which was named Ashbrook at the time. That same year, Ashbrook helped lay out the town with the building of 25 new houses.[9]

In 1853, Ashbrook, was voted to the Railroad Committee for the speedy construction for rails to cover Ross, Pickaway, and Franklin Counties.[10] The route of the railroad (like the canals before it) had a great effect on the success of the development of the area. Ashbrook manufactured barrels for the mill and distillery, and also had some outside trade in that line.

The Ashbrook businesses failed in 1855, following his endorsement of a promissory note for a friend. When the friend failed to pay, Ashbrook was in debt for tens of thousands of dollars and lost much of his wealth to his creditors.[11] Ashbrook migrated west, leaving part of his family behind.

Like most of America, the town suffered a setback due to the Panic of 1857. The growth of the town was further hampered by the onset of the American Civil War.

Railroad boom

The construction of the Scioto Valley Railroad through Ashville, under the supervision of lead engineer Isham Randolph, began in 1874. This caused a new flurry of both population and economic growth, including the building of two new grain elevators. Railroad employees, most notably bridge builders, settled in the northern reaches of Ashville in what has become Little Chicago.[12] A year later, in 1875, the post office was reestablished after it had been closed following the shuttering of the Ashbrook businesses and a train station was opened in 1876. Finally, after nearly 70 years following the original settlement, the village was incorporate as Ashville in the Spring of 1882.

In 1890, the population of Ashville reached 430 citizens and the area's first volunteer fire department was created, as well as cisterns were built throughout the village. That same year, Norfolk and Western Railway acquired the Scioto Valley Railroad following its demise.

.jpg.webp)

Over the next ten years, the village population grew at a rate of more than 50%. This was aided by the establishment of major businesses, which included the Scioto Valley Canning Factory that was built in 1899. The factory, which canned sweet corn, at its peak, employed 540 employees who were able to produce upwards of 200,000 cans of corn per day. Dozens of other businesses sprang up as well to accommodate the growth, including blacksmiths, a lumber yard, a hotel, and even an opera house.[9]

In 1904, Scioto Valley Traction Company opened a railway in town that powered their engines by electricity using a third rail. This line sent passenger and freight traffic from Columbus to Chillicothe. The line operated until September 1930. The depot remains on West Main Street.[13]

Around 1910, the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway (which later became CSX) was built on the western edge of town. With the construction several gandy dancers settled in Little Chicago. The workers were primarily of Greek and Bulgarian descent according to Census records.[12] The population of the town had ballooned to over 970 by that time.

Following Ashville's quick growth, it became the second most populated area in Pickaway County.

Small town status

Though the rail lines remained operational, the population growth of the village slowed. Over the next three decades the population grew by only 129 citizens. Additionally, the reduction of growth was compounded by the effects of the Great Depression.

A population spike happened again in the 1950s and 1960s as Ashville became a residential town when new homes started popping up west of Long Street. Though many businesses had fizzled out, new large employers began to target Ashville including Columbus Industries which opened their plant in 1970.[14] During this time Ashville also became the hub of a newly formed school district when Teays Valley Local School District built their high school in 1963 and housed their district offices within the village.

The next major growth step happened in 1994 when home builders, such as M/I Homes, built the first modern subdivisions in Ashville.[15] The two major subdivisions were Ashton Village and Ashton Woods, which are located on the northside of town. Both sites together brought in nearly 100 new homes.

Continued growth

Since 1990, Ashville remains one of the fastest growing areas in Pickaway County. Several new housing developments, apartments, and condominiums have been built and the expansion of Rickenbacker International Airport Global Logistics Park and the Norfolk Southern Railway Intermodal Terminal, that was built in 2008, have created thousands of jobs for the area.[16]

Geography

Ashville is located at 39°43′06″N 82°56′54″W / 39.7183399°N 82.9483270°W.[17] It is located in the Scioto River Valley and has an elevation of 715 feet (218 m) above sea level.[18] The village is located in the till plain-area of Western Ohio and borders the Appalachian Plateau. The area is generally viewed to be a fertile region with gently rolling hills created by moraines.[19]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the village has a total area of 2.51 square miles (6.50 km2), all of it land.[20]

Glacial activity

The area on which present-day Ashville sits was effected by three glacial periods. Those periods were Pre-Illinoian Glaciation, Illinoian Glaciation, and Wisconsin glaciation.[21]

- Pre-Illinoian Glaciation - The first impact of glaciers in Ashville occurred about 780,000 years ago during the Pleistocene epoch. The glacier, which stopped right at Ashville's location, dammed the pre-glacial Teays River just south of the village, which created Lake Tight. The former Teays River would go on to become a significant aquifer for the area.

- Illinoian Glaciation - Approximately 190,000 to 130,000 years ago, a glacier once again covered the area. Much of the effects of this glacier were covered by the subsequent Wisconsin glaciation that started 100,000 years later.

- Wisconsin Glaciation - The last ice to be in the area began 35,000 years ago and ended approximately 12,000 years ago. The Laurentide Ice Sheet stretched into Ohio with the Lake Huron lobe being the most prominent major lobe. The Scioto minor lobe, which helped create the Scioto River, stretched over the area and created the modern day terrain.

Rivers, creeks, and brooks

The Village is part of the Walnut Creek watershed.[22] Walnut Creek is a tributary of the Scioto River that forms the southern border of Ashville and runs into the river approximately 2.5 miles southwest of the village. The Walnut Creek is intersected by the Little Walnut Creek approximately .25 miles southeast of the village and by Mud Run, a brook that runs through the western fringes of the village, 1.7 miles southwest.

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1890 | 430 | — | |

| 1900 | 654 | 52.1% | |

| 1910 | 972 | 48.6% | |

| 1920 | 1,032 | 6.2% | |

| 1930 | 1,085 | 5.1% | |

| 1940 | 1,101 | 1.5% | |

| 1950 | 1,303 | 18.3% | |

| 1960 | 1,639 | 25.8% | |

| 1970 | 1,772 | 8.1% | |

| 1980 | 2,046 | 15.5% | |

| 1990 | 2,254 | 10.2% | |

| 2000 | 3,174 | 40.8% | |

| 2010 | 4,097 | 29.1% | |

| 2020 | 4,529 | 10.5% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[23] | |||

2010 census

As of the census[24] of 2010, there were 4,097 people, 1,598 households, and 1,100 families living in the village. The population density was 1,632.3 inhabitants per square mile (630.2/km2). There were 1,731 housing units at an average density of 689.6 per square mile (266.3/km2). The racial makeup of the village was 96.7% White, 1.0% African American, 0.4% Native American, 0.3% Asian, 0.1% from other races, and 1.4% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino people of any race were 1.4% of the population.

There were 1,598 households, of which 41.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 45.7% were married couples living together, 15.6% had a female householder with no husband present, 7.6% had a male householder with no wife present, and 31.2% were non-families. 25.5% of all households were made up of individuals, and 8.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.56 and the average family size was 3.05.

The median age in the village was 32.8 years. 29.3% of residents were under the age of 18; 9.8% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 29.6% were from 25 to 44; 21.9% were from 45 to 64; and 9.5% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the village was 48.5% male and 51.5% female.

2000 census

As of the census[3] of 2000, there were 3,174 people, 1,243 households, and 872 families living in the village. The population density was 2,035.8 inhabitants per square mile (786.0/km2). There were 1,337 housing units at an average density of 857.5 per square mile (331.1/km2). The racial makeup of the village was 97.83% White, 0.19% African American, 0.32% Native American, 0.06% Asian, 0.19% from other races, and 1.42% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino people of any race were 1.07% of the population.

There were 1,243 households, out of which 40.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 52.5% were married couples living together, 13.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 29.8% were non-families. 24.9% of all households were made up of individuals, and 9.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.55 and the average family size was 3.03.

In the village, the population was spread out, with 29.6% under the age of 18, 9.6% from 18 to 24, 33.8% from 25 to 44, 17.7% from 45 to 64, and 9.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 31 years. For every 100 females there were 93.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 85.3 males.

The median income for a household in the village was $40,778, and the median income for a family was $47,092. Males had a median income of $35,236 versus $22,231 for females. The per capita income for the village was $16,645. About 6.3% of families and 9.5% of the population were below the poverty line, including 11.5% of those under age 18 and 6.0% of those age 65 or over.

Government

Ashville is governed by the mayor–council system of government. It consists of a mayor and six council members at-large, all elected by village residents. Since 1985, elected offices are non-partisan and serve four-year terms.[25]

Mayor

The mayor is responsible for overseeing the village's police department, appointing and managing village employees, presiding over Mayor's Court, and overseeing the village's finances. In addition to independent duties, the mayor is the president of the Council, but does not vote unless there is a tie.[26]

The current mayor of Ashville is Nelson Embrey II following the death of Charles (Chuck) Wise who was the longest serving mayor, having served in the capacity for 22 years.

List of mayors

As of 2024[27]

- 1882–1884; 1886: W. R. Julian

- 1885: Charles Steward

- 1887–1889: S. D. Fridley

- 1890–1896: W. M. Miller

- 1897–1900: A. S. Longenbaugh

- 1901–1902: E. S. Workman

- 1903–1905: G. A. Hook

- 1906–1907; 1932–1935; 1938–1939: E. E. Frunfelter

- 1908: H. J. Bond

- 1909–1911; 1926–1927: E. E. Smith

- 1912–1919: G. W. Morrison

- 1920–1921: John Wilson

- 1922–1923: A. E. Reichelderfer

- 1924–1925: G. T. Peters

- 1925; 1928–1929: J. L. Spindler

- 1930–1931: S. D. Fridley

- 1936–1937: Harry Margulis

- 1940–1943: Fred J. Hines

- 1944–1945: Tom R. Acord

- 1946–1947: Harry A. Litten

- 1948–1951: Elmer Malone

- 1952–1954: Raymond R. Lindsey

- 1955–1962: Richard B. Bozman

- 1963–1967: Charles W. Morrison

- 1968–1974: Harold Hartley

- 1975: James Hopper

- 1975–1979: Max Cormany

- 1980–1982: Albert Johnston

- 1982–1992: Marvin Hicks

- 1992–1995: Peggy Pritchard

- 1995–2000: Jane Cline

- 2000–2023: Charles K. Wise

- 2023: Nelson Embrey II

- 2024–present: Steve Welsh

Village council

The village council holds legislative authority over the municipality and performs no administrative duties. The body passes ordinances and resolutions to manage and control the village's development, finances, and property. As of 2023, the council members are Randy Loveless (President pro tempore), Roger L. Clark, Colton Henson, David Rainey, and Matt Scholl.[28]

Education

Schools

Teays Valley Local Schools

Prior to 1963, Harrison Township and the village had operated Ashville Harrison School which graduated its last class in 1962, and had 44 students.[29] The district combined with two neighboring districts in the Fall of 1962 to form Teays Valley.[30] The district currently operates three schools within the village's boundaries, which include Teays Valley High School, East Middle School, and Ashville Elementary.[31]

Brooks-Yates School

Brooks-Yates was a school operated by Pickaway County Board of Developmental Disabilities that provided services to Pickaway County students with developmental disabilities. The school was moved to Teays Valley's main campus in Ashville from Circleville in 2016.[32] The school ultimately closed in 2021, following a decline in enrollment.[33]

CSCC – Pickaway County Center

A regional campus of Columbus State Community College was once located at Teays Valley High School. As of 2022, the campus is no longer active.

Library

Ashville has a public library, located on Long Street. The Floyd E. Younkin Branch is part of the Pickaway County Library system and was opened in 1999 after local business owners, the Younkin family, donated funds to open the location.[34][35]

Arts and culture

Churches

Five Christian churches operate within the village limits. The churches that are currently operating are Ashville Church of Christ in Christian Union, Heritage Church of Christ, First English Lutheran Church, Village Chapel Church, and Zion United Methodist Church. First English Lutheran was the founding member of the Ashville Food Pantry which is located on Long Street at the village's center.[36]

Community Park

Ashville has one public park which is called the Ashville Community Park. The 10-acre park was deeded to the community on April 4, 1921, with the stipulation that the village used it for athletic and park purposes, by a community club that had purchased the tract a year earlier for $3,000. The club also built an indoor shelter house before donating the land. Shortly after the acquisition, the village built a baseball field with concrete bleachers and a quarter-mile cinder track for community and school use. Ashville went on to install a playground, an outdoor shelter house, tennis courts, basketball courts, restrooms and a gazebo.[30] The park is host location of the annual Fourth of July Celebration and Viking Festival.

Fourth of July Celebration

Ashville's Fourth of July Celebration has taken place since 1929, and annually brings thousands of people to the community.[37] Hosted by the Ashville Community Men's Club, the five-day event includes concessions, rides, a queen contest, a daily fish fry, musical entertainment, parades, and a community church service. The carnival is held at Ashville Community Park, at the village's center. Fireworks cap the celebration on Independence Day night and are fired from the Teays Valley High School property.[38]

Viking Festival

The Spring festival, which started in the mid-2000s, is a two-day festival that pays homage to ancient Scandinavian culture. Hundreds of people gather at the Ashville Community Park where reenactors take up the lifestyle of the Vikings and enjoy music, food, and handcrafted goods of the time period. A Viking ship replica is located at the center of the camp along with jousting and swordsmanship exhibitions. The festival was on a temporary hiatus in 2020 and 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[39] In 2022, the festival returned with the addition of a beer garden.

Museums

Ashville Depot

The Ashville Depot is a former, and the only remaining, train station for the Scioto Valley Railway. Built in 1876 and closed in 1976, this weatherboard building was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1980. It is located at the intersection of Madison and Cromley Streets.[40] The building acts as a meeting place and railroad museum. It is currently owned and operated by the Ashville Community Men's Club.[41]

Ohio's Small Town Museum

In 1978, the Ashville Area Heritage Society opened what became Ohio's Small Town Museum in a former silent film theater, known by locals as the Rocky Dreamland Theatre. The project was spearheaded by longtime village leader Charlie Morrison. The museum is home to local memorabilia including a 17-star United States flag, a buoy from the sunken battleship, USS Maine, and the still-working traffic light that was invented by resident Teddy Boor in 1932.[42] The museum claims that the traffic light is the world's oldest traffic light, a claim that the village itself supports.[43] This claim was again supported by Guinness World Records by naming it the Oldest Functioning Traffic Light.[44]

Old Town Jail Museum

The Old Town Jail Museum is located at the corner of Cherry and Long Streets. Built in 1886, the building served as police headquarters until 1988. In 2021, the village established a museum that pays tribute to the village's criminal justice history. Other parts of the building are used for Council chambers and the village's streets department.[45]

Notable residents

- Harley H. Christy, World War I hero and Vice Admiral

- Champ Henson, former Cincinnati Bengals player

- Ron Hood, politician and 2022 Ohio gubernatorial candidate

- John Holmes, pornographic actor

- William Ashbrook Kellerman, mycologist, journal founder, explorer and photographer

- Isham Randolph, Chicago and Panama Canal civil engineer

- Brian Stewart, politician

- Seth Mosley, Christian music singer and producer

References

- ↑ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- 1 2 "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- 1 2 "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ↑ "Snake Den Mound excavation". Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ↑ "Pickaway County, Ohio - About Pickaway County". www.pickaway.org. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- ↑ "Shawnee | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- ↑ Knepper, George (2002). The official Ohio lands book. Columbus, Ohio: Ohio Auditor of State. p. 43.

- ↑ "Patent Details - BLM GLO Records". glorecords.blm.gov. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- 1 2 Van Cleaf, Aaron (1906). History of Pickaway County, Ohio, and Representative Citizens. Chicago, IL: Biographical Publishing Company (published 1978). pp. 127–128.

- ↑ "Railroad Record, and Journal of Commerce, Banking, Manufactures and Statistics". 1853.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Biography Found in Portrait and biographical record of Buchanan and Clinton counties, Missouri. p. 422.

- 1 2 Hines, Bob (February 1, 2020). "Scioto Valley Railroad Bridge Builders and Greek Gandy Dancers in Ashville" (PDF). Official Newsletter of Ohio’s Small Town Museum. pp. 11–12. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- ↑ "Scioto Valley Transit Company". www.railsandtrails.com. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- ↑ "D1300050000238 - County Auditor Website, Pickaway County, Ohio". auditor.pickawaycountyohio.gov. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- ↑ "D1300310000107 - County Auditor Website, Pickaway County, Ohio". auditor.pickawaycountyohio.gov. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- ↑ "Rickenbacker International Airport (LCK) | Cargo, Freight, Transportation & Logistics". rickenbackeradvantage.com. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ↑ "Geographic Names Information System". edits.nationalmap.gov. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ↑ "Ohio's Geological Regions". touringohio.com. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 25, 2012. Retrieved January 6, 2013.

- ↑ Division of Geological Survey. "The Ice Age in Ohio". Ohio Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ↑ "Walnut Creek Watershed". balancedgrowthplanning.morpc.org. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 6, 2013.

- ↑ Village of Ashville Council. "CODIFIED ORDINANCES OF ASHVILLE / PART ONE - ADMINISTRATIVE CODE" (PDF). Village of Ashville. Retrieved April 12, 2022.

- ↑ Ashville Village Council. "Duties of Mayor" (PDF). Village of Ashville. Retrieved April 12, 2022.

- ↑ Wise, Charles. "Ashville Mayors History" (PDF). Village of Ashville. Retrieved April 12, 2022.

- ↑ "Village Council". ashvilleohio.gov. Retrieved April 12, 2022.

- ↑ "Ashville Harrison High School Reunion - Class of 1962". Circleville Herald. Retrieved April 12, 2022.

- 1 2 Fullen, Larry (2010). The Broncos of 1945. Bloomington, Indiana: AuthorHouse. ISBN 9781449077211.

- ↑ "Teays Valley High School". Teays Valley Local School District. Retrieved March 3, 2018.

- ↑ "Ohio Association of County Boards of DD - Brooks-Yates School considers possible relocation". www.oacbdd.org. Retrieved April 12, 2022.

- ↑ "Brooks-Yates School To Close". Retrieved April 12, 2022.

- ↑ "Locations". Pickaway County Library. Archived from the original on March 3, 2018. Retrieved March 3, 2018.

- ↑ "In the Books: Floyd e. Younkin Library celebrates 15 years".

- ↑ Wise, Charles K. (October 28, 2020). "The Mayor's Column - Ashville Food Pantry" (PDF). The Friendly Community Newsletter. p. 1. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ↑ "Ashville 4th of July Celebration | About". ashville4thofjuly.com. Retrieved April 12, 2022.

- ↑ WSYX Staff (May 25, 2021). "2021 Fourth of July fireworks and celebrations". WSYX. Retrieved April 12, 2022.

- ↑ Collins, Steven. "Viking Festival survives Ragnarok to return in 2022". Circleville Herald. Retrieved April 12, 2022.

- ↑ "Details | Ohio National Register Searchable Database Application". nr.ohpo.org. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ↑ "D1300050001300 - County Auditor Website, Pickaway County, Ohio". auditor.pickawaycountyohio.gov. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ↑ Ludlow, Randy. "Museum shows off quaint, quirky" (PDF). The Columbus Dispatch. pp. B2. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ↑ "World's Oldest Traffic Light, Ashville, Ohio". RoadsideAmerica.com. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ↑ "Oldest functional traffic light". Guinness World Records. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ↑ Reporter, STEVEN COLLINS Circleville Herald Senior. "Old Town Jail Museum opens in Ashville". Circleville Herald. Retrieved April 13, 2022.