International Workers' Association | |

Asociación Internacional de los Trabajadores | |

.jpg.webp) | |

| Founded | December 1922 |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | C/Joaquim Costa 34 baixos Barcelona, Spain |

| Location |

|

| Affiliations | Anarcho-syndicalism |

| Website | www |

| Part of a series on |

| Anarcho-syndicalism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Anarchism |

|---|

|

The International Workers' Association – Asociación Internacional de los Trabajadores (IWA–AIT) is an international federation of anarcho-syndicalist labor unions and initiatives.

It aims to create unions capable of fighting for the economic and political interests of the working class and eventually, to directly abolish capitalism and the state through "the establishment of economic communities and administrative organs run by the workers."

At its peak the International represented millions of people worldwide. Its member unions played a central role in the social conflicts of the 1920s and 1930s. However the International was formed as many countries were entering periods of extreme repression, and many of the largest IWA unions were shattered during that period.[1]

As a result, by the end of World War II all but one of the International's branches had ceased to function as unions, a slump which continued throughout the 1940s and 1950s. It would not be until the late 1970s, with the death of Spanish caudillo Francisco Franco, that it would see a major union, the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT) reform within its ranks.

After the 1970s, the International expanded and currently counts 14 member sections and 6 Friends.

Ideology

The IWA programme promotes a form of non-hierarchical unionism which seeks to unite workers to fight for economic and political advances towards the final aim of libertarian communism.

This federation is designed to both contest immediate industrial relations issues such as pay, working conditions and labor law, and pursue the reorganization of society into a global system of economic communes and administrative groups based within a system of federated free councils at local, regional, national and global levels. This reorganization would form the underlying structure of a self-managed society based on pre-planning and mutual aid—the establishment of anarchist communism.

The IWA's Principles, Goals and Statutes state its role as being: "To carry on the day-to-day revolutionary struggle for the economic, social and intellectual advancement of the working class within the limits of present-day society, and to educate the masses so that they will be ready to independently manage the processes of production and distribution when the time comes to take possession of all the elements of social life.[2]"

The IWA explicitly rejects centralism, political parties, parliamentarism and statism, including the idea of the dictatorship of the proletariat, as offering the means to carry out such change, drawing heavily on anarchist critiques written both before and after the Russian revolution, most famously Mikhail Bakunin's suggestion that: "If you took the most ardent revolutionary, vested him in absolute power, within a year he would be worse than the Tsar himself."[3]

It also rejects the concept of economic determinism from some Marxists that liberation would come about; "by virtue of some inevitable fatalism of rigid natural laws which admit no deviation; its realization will depend above all on the conscious will and the use of revolutionary action of the workers and will be determined by them."[4]

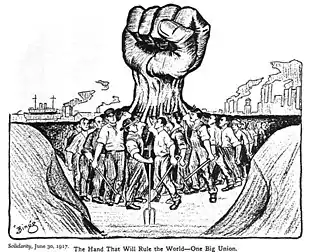

Instead emphasis is placed on the organization of workers as the agents of social change through their ability to take direct action:

Revolutionary unionism asserts itself to be a supporter of the method of direct action, and aids and encourages all struggles that are not in contradiction to its own goals. Its methods of struggle are: strikes, boycotts, sabotage, etc. Direct action reaches its deepest expression in the general strike, which should also be, from the point of view of revolutionary unionism, the prelude to the social revolution.

...

Only in the economic and revolutionary organisations of the working class are there forces capable of bringing about its liberation and the necessary creative energy for the reorganisation of society on the basis of libertarian communism.

— Statutes of the IWA[5]

Policies

The IWA rejects all political and national frontiers; it calls for radical changes to the means of production to lessen humanity's environmental impact.

From an early stage, the IWA has taken an anti-militarist stance, reflecting the overwhelming anarchist attitude since the First World War that the working class should not engage with the power struggles between ruling classes - and certainly should not die for them. It included a commitment to anti-militarism in its core principles and in 1926 it founded an International Anti-Militarist Coalition to promote disarmament and gather information on war production.[6]

While regarding industrial acts such as strikes, boycotts, etc. as the primary means of struggle against capitalist and state exploitation, the founding document of the IWA also states that syndicalists recognize "as valid that violence that may be used as a means of defense against the violent methods used by the ruling classes during the struggles that lead up to the revolutionary populace expropriating the lands and means of production."

It is stressed that this should occur through the formation of a democratic popular militia rather than through a traditional military hierarchy. This has been posited as an alternative to the dictatorship of the proletariat model.[6]

Organization

The IWA admits organizations which are in full agreement with its Aims and Principles[5] in countries where there is not already an affiliated group in existence, requiring them to pay affiliation fees to help maintain the IWA's structure.

Member groups are then able to participate in and benefit from the global community the IWA provides and can vote in its highest decision-making event, the International Congress, which is currently held once every two years. Proposals are submitted at national level at least six months before congress, to allow other national groups to consult and mandate members to vote. The agreements and resolutions adopted by the International Congresses are binding for all affiliated groups.

The sample flowchart on the right shows the relationship of the individual to the organization within Britain and Ireland IWA affiliate the Solidarity Federation. If an individual wishes to change the organization's policies, they must win agreement from their Local to formally place the idea before Federal Conference, which in turn, if other Locals agree, may place the idea before the IWA as a whole for a decision. While federal officers are mandated by the Federal Conference, they have no influence over policymaking other than through their own Locals.

No permanent positions of paid or elected authority are present at any stage within the international and its affiliates. Instead, unpaid volunteer positions are created to deal with administrative issues, and individuals are restricted to carrying out these activities within a mandate decided directly by their peers and subject to instant recall. Beyond the collective agreements of the IWA itself, all decision-making takes place within base units (such as Locals) organized by geography or trade, as most applicable (where industrial organizing is not possible due to low density, geographical units are the norm).

Administration of the IWA's functions is carried out by the Secretariat consisting of at least three people living in the country nominated by the International to take on the role. The IWA also elects a Secretary General, who acts as a liaison and representative for the International but again, does not wield any direct powers over policy. The Secretariat may only hold office for two terms concurrently. For specific tasks, such as financial audits, separate commissions are set up.

Internal communications are maintained through each member group's International Secretaries, and through wide circulation of members' own internal publications. Informal online communication is also a mainstay of this process.

History

First International and revolutionary syndicalism (1864–1917)

The early ideology of revolutionary syndicalism from which the IWA derives was formed during the International Workingmen's Association (IWMA), also known as the First International.

The First International aimed at uniting a variety of different left-wing socialist, communist[7] and anarchist political groups and Labor union that were based on the working class and class struggle.

The earlier International however was not able to withstand the differences between anarchist and Marxist currents, with the anarchists largely withdrawing after the Hague Congress of 1872 which saw the expulsion of leading libertarians Mikhail Bakunin and James Guillaume over their criticism of Karl Marx's party-political approach to social change.[8]

This split prompted several attempts to start specifically anarchist Internationals, notably the Anarchist St. Imier International (1872-1881) and the Black International (1881–87). However heavy repression in France of the Paris Commune, as well as in Spain and Italy, alongside the rise of propaganda of the deed within the anarchist movement and a dominant strand of social-democracy on the wider left wing in Europe, meant that serious moves to establish an anarcho-syndicalist international would not begin until the early 20th century.[1][9]

The 1900s saw a major leap forward for the labor movement with the adoption of a new method of organizing, industrial unionism and in 1913 there was an international syndicalist congress held in London which aimed at building stronger ties between the existing syndicalist unions and propaganda groups. Present at the congress were delegates from the FVdG (Germany), NAS (Netherlands), SAC (Sweden), USI (Italy), and ISEL (Britain). Observers attended from the Industrial Workers of the World (US), CNT (Spain), and FORA (Argentina).

The Congress' outcome was inconclusive, beyond drawing up a declaration of principles and setting up a short-lived information bureau. The burgeoning movement was to be snuffed out within a year as Europe was plunged into World War I and communications between the syndicalists became impossible.

After the end of the war however, with the workers' movement resurgent following the October Revolution and subsequent Russian Civil War, what was to become the modern IWA was formed, billing itself as the "true heir" of the original international.[10]

Rejection of Bolshevism and founding of the IWA (1918–1922)

The success of the Bolsheviks in Russia in 1918 resulted in a wave of syndicalist successes worldwide, including the struggle of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in the USA alongside the creation of mass anarchist unions across Latin America and huge syndicalist-led strikes in Germany, Portugal, Spain, Italy and France, where it was noted that "neutral (economic, but not political) syndicalism had been swept away."[1]

For many in this new revolutionary wave, Russia seemed to offer a successful alternative to social democratic reformism, so when in 1919 the Bolshevik Party issued an appeal for all workers to join it in building a new Red International it was met with great interest. Almost all of the syndicalist unions attended the 1920 congress of the Bolsheviks’ international of communists, the Comintern, which unions in France and Italy joined immediately.[9] In contrast, attempts to organize a conference of anarchists in February 1919 in Copenhagen had seen only the Scandinavians able to attend.[1]

Skepticism was initially expressed by Germany's influential Free Workers' Union of Germany (FAUD) towards the Bolsheviks' concept of an international of trade unions, known as the Profintern. Such sentiments grew significantly as delegates from several countries gained access to Bolshevik Russia. Augustine Souchy of FAUD scathingly criticised the failings of "dictatorial state socialism," as concerns rose over proposals from the Bolsheviks that all unions should submit themselves to the Communist Party's leadership and reports began to arrive documenting the imprisonment of anarchists and socialists by the Bolsheviks.[11]

At the Profintern's formal launch in July 1921, these fears proved well founded with the passing of a resolution subordinating the Profintern to the Comintern and thus tying the priorities of all member unions to those of the Russian state. While initially the syndicalist organizations present, including the largest unions from Spain (CNT), Italy (USI), Argentina (FORA), Germany (FAUD) and the USA (IWW) agreed to join on condition that organizational independence would be maintained, relations soured over the course of the year.

By 1922 relations had broken down completely and the Profintern was decisively condemned at a conference of syndicalist unions in Berlin on June 16–18, after a Russian delegate repeatedly refused calls to press for the release of independent and anarchist trade unionists from Lenin's prisons. Delegations from France, Germany, Norway and Spain resolving to establish a bureau to prepare the ground for the founding of a new international, rejecting parliamentarianism, militarism, nationalism and centralism.

The final formation of this new international, then known as the International Workingmen's Association, took place at an illegal conference in Berlin in December 1922, marking an irrevocable break between the international syndicalist movement and the Bolsheviks.[1]

Signatories to the founding statement of the International Workingmen's Association included groups from around the world. The single largest anarcho-syndicalist union at the time, the CNT in Spain, was unable to attend when their delegates were arrested on the way to the conference, though they did join the following year, bringing 600,000 members into the international. Despite the CNT's absence, the international represented well over 1 million workers at its inauguration:[12]

- The Italian Syndicalist Union (USI): 500,000 members

- The Regional Federation of Argentine Workers (FORA): 200,000

- The General Confederation of Labour (CGT) in Portugal: 150,000

- The Free Workers' Union of Germany (FAUD): 120,000

- The Committee for the Defense of Revolutionary Syndicalism in France: 100,000

- The Central Organisation of the Workers of Sweden (SAC): 32,000

- The General Confederation of Workers (CGT) in Mexico: 30,000

- The National Labor Secretariat (NAS) in the Netherlands: 22,500

- The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in Chile: 20,000

- The Norwegian Syndicalist Federation (NSF) in Norway: 20,000

- The Union for Syndicalist Propaganda in Denmark: 600

The first secretaries of the International included the famed writer and activist Rudolph Rocker, along with Augustin Souchy and Alexander Schapiro.

Following the first congress, other groups affiliated from France, Austria, Denmark, Belgium, Switzerland, Bulgaria, Poland and Romania. Later, a bloc of unions in the US, Colombia, Peru, Ecuador, Guatemala, Cuba, Costa Rica and El Salvador also shared the IWA's statutes.

The biggest syndicalist union in the US, the IWW, considered joining but eventually ruled out affiliation in 1936, citing the IWA's policies on religious and political affiliation.[13][14]

Decline and repression (1923–1939)

Many of the largest members of the IWA were broken, driven underground or wiped out in the 1920s-30s as powers hostile to them came to power in states across Europe and workers switched away from anarchism towards the seeming success of the Bolshevik model of socialism.

In Argentina, the FORA had already begun a process of decline by the time it joined the IWA, having split in 1915 into pro and anti-Bolshevik factions. From 1922, the anarchist movement there lost most of its membership, exacerbated by further splits, most notably around the Severino Di Giovanni affair. It was crushed by General Uriburu's military coup in 1930.[15]

Germany's FAUD struggled throughout the late 1920s and early 30s as the brownshirts took control of the streets. Its last national congress in Erfurt in March 1932 saw the union attempt to form an underground bureau to combat Hitler's National Socialists, a measure which was never put into practice as mass arrests decimated the conspirators' ranks. The editor of FAUD organ Der Syndikalist, Gerhard Wartenberg, was later killed in Sachsenhausen concentration camp, and Karl Windhoff, delegate to the IWA Madrid congress of 1931, was driven out of his mind and also died in a death camp. Mass trials of FAUD members were also held in Wuppertal and Rhenanie; many of those convicted did not survive the death camps.[16]

Italian IWA union the USI, which had claimed a membership of up to 600,000 people in 1922, was warning even at that time of murders and repression from Benito Mussolini's blackshirts.[17] It had been driven underground by 1924 and although it was still able to lead significant strikes by miners, metalworkers and marble workers, Mussolini's ascent to power in 1925 sealed its fate. By 1927 its leading activists had been arrested or exiled.[18]

Portugal's CGT was driven underground after an unsuccessful attempt to break the newly installed President of Portugal, Gomes da Costa, with a general strike in 1927 which led to nearly 100 deaths. It survived underground with 15–20,000 members until January 1934, when it called a general revolutionary strike, which failed, against plans to replace trade unions with corporations. It was able to continue in a much reduced state until World War II, but was effectively finished as a fighting union. Massive government repression repeated such defeats around the world, as anarcho-syndicalist unions were destroyed in Peru, Brazil, Columbia, Japan, Cuba, Bulgaria, Paraguay and Bolivia. By the end of the 1930s legal anarcho-syndicalist trade unions existed only in Chile, Bolivia, Sweden and Uruguay.[1]

But perhaps the greatest blow was struck in the Spanish Civil War, which saw the CNT, then claiming a membership of 1.58 million, driven underground with the defeat of the Spanish Second Republic by the Nationalists. The sixth IWA congress took place in 1936, shortly after the Spanish Revolution had begun, but was unable to provide serious material support for the section.

The IWA held its last pre-war congress in Paris in 1938, months before the German invasion of Poland that started the Second World War. It received an application from ZZZ, a syndicalist union in Poland claiming up to 130,000 workers – ZZZ members went on to form a core part of the resistance against the Nazis, and participated in the Warsaw Uprising. But the International did not meet again until 1951, years after the end of the war. During the war only one member of the IWA was able to continue to function as a revolutionary union, the SAC in Sweden.

After Hitler's defeat, much of the Spanish CNT's active membership, now operating informally in Francoist Spain, remained split, with some in exile in France and Britain and the rest driven underground. In Sweden the SAC retained a presence, while in every other country previously active members of the International had to start from scratch.

Relaunch of the International Workers Association (1951–1980)

At the seventh congress in Toulouse in 1951 a much smaller IWA was relaunched, again without the CNT, which would not be strong enough to reclaim membership until 1958 as an exiled and underground organization. Delegates attended, mostly representing very small groups, from Cuba, Argentina, Spain, Sweden, France, Italy, Germany, the Netherlands, Austria, Denmark, Norway, Britain, Bulgaria and Portugal. A message of support was received from Uruguay.

But the situation remained difficult for the International, as it struggled to deal with the rise of state-sanctioned economic trade unionism in the West, heavy secret service intervention as Cold War anti-communism reached its height and the banning of all strikes and free trade unions in the Soviet Union bloc of countries.

At the tenth congress in 1958, the SAC's response to these pressures led it into a clash with the rest of the international. It withdrew from the IWA following its failure to amend the body's statutes to allow it to stand in municipal elections[19] and amid concerns over its integration with the state over distribution of unemployment benefits.[6]

For most of the next two decades, the International struggled to rebuild itself.

In 1976, at the 15th congress, the IWA had only five member groups, two of which (the Spanish and Bulgarian members) were still operating in exile (though following Franco's death in 1975, the CNT was already approaching a membership of 200,000).[17]

In 1979 a split over representative unionism, professional unionism and state-funded schemes saw the CNT split, resulting in the CGT today.

Revival and the modern period (1980s and 90s)

The IWA's 1980 congress showed much improvement, reaching ten sections and benefiting from the reorganization of the CNT, which was able to send delegates from Spain (as opposed to exiles) for the first time since the 1930s. Reformed sections in Italy (USI) and Norway (NSF), along with others from the UK (Direct Action Movement), USA (Workers Solidarity Alliance), Germany (Free Workers' Union, FAU) and Australia Anarcho-Syndicalist Federation,[20] were among those who joined.

All existing groups reported growth, and by 1984 at its 17th congress the International had three unions as members: CNT of Spain, CNT of France, and USI of Italy. The IWA grew throughout the decade, adding two new groups, one from Japan and the other from Brazil (Confederação Operária Brasileira).

Further growth was recorded in the 1990s, although the Workers Solidarity Alliance along with the Japanese and Australian sections ceased to be members. However the 1996 Congress saw two sections split over the question of participation in trade union elections, with the French section divided into the CNT-F (also known as CNT Vignoles) and CNT-AIT[21] sections (the latter becoming the official IWA affiliate), while the Italian USI's "Roman tendency" was expelled. Czech, Slovak and Russian sections were added at the same event. Four years later, the Serbian and Brazilian sections joined.

Conflict and ICL-CIT split (2000s onward)

In September 2014, the Free Workers' Union was suspended by the IWA Secretariat over its decision to establish links with non-IWA unions, a decision confirmed by a majority of sections at an extraordinary congress held in December 2014. The suspension rendered the FAU ineligible to vote and barred it from all internal communication.[22] The IWA disaffiliated the FAU, CNT, and USI at its 26th congress in 2016.[23] Part of the CNT wished to remain affiliated to the IWA.[24]

In June 2016, the first meeting was held in Spain concerning the reconstruction of the Spanish section of the IWA. A subsequent Congress was held in Benissa in November 2016 and Villalonga in April 2017 to reconstruct the CNT-IWA. The issue of the reintegration of the reconstructed Spanish section was on the agenda of an Extraordinary Congress of the IWA in 2017, where the Section in Spain was recognized as the continuation of the CNT-IWA.[25]

In 2018, former IWA members met with other groups in Parma, Italy, to establish a new international organization, the International Confederation of Labor (Confederación Internacional del Trabajo), otherwise known as ICL-CIT. Affiliated organisations include CNT (Spain), USI (Italy), FAU (Germany), the North American Regional Administration of the IWW, ESE (Greece), FORA (Argentina) and IP (Poland).[26]

Member organisations

The following organizations are either Sections or Friends of the IWA.[27]

Other anarchist internationals and international networks

- Anarchist St. Imier International (1872–1877)

- International Working People's Association (1881–1887)

- International of Anarchist Federations (1968–)

- Black Bridge International (2001–2004)

- International Libertarian Solidarity (2001–2005)

- Anarkismo.net (2005–)

- International Confederation of Labour (2018-)

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Vadim Damier (2009), Anarcho-syndicalism in the 20th Century

- ↑ "Going Global - International Organisation, 1872-1922" (PDF). Selfed. 2001. Retrieved 2009-09-29.

- ↑ Daniel Guerin, Anarchism: From Theory to Practice (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1970), pp.25-26.

- ↑ "economic determinism meaning - economic determinism definition". eng.ichacha.net. Retrieved 2022-01-04.

- 1 2 "The Statutes of Revolutionary Unionism (IWA)". IWA. 2022-12-09.

- 1 2 3 Michael Schmidt and Lucien Van Der Walt (2009), Black Flame

- ↑ "Dictionary of politics: selected American and foreign political and legal terms". Walter John Raymond. p. 85. Brunswick Publishing Corp. 1992. Accessed January 27, 2010.

- ↑ "1860-today: The International Workers Association". Libcom.org. 2006. Retrieved 2009-09-29.

- 1 2 Rudolph Rocker (1960), Anarchism and Anarcho-Syndicalism

- ↑ Wayne Thorpe (1989), The Workers Themselves

- ↑ Memoria que al Comité de la CNT presenta de su gestión en el II Congreso de la Tercera Internacional (19 de julio - 7 de agosto de 1920) el delegado Ángel Pestaña

- ↑ Rocker, Rudolf (2014). Anarchism and Anarcho-Syndicalism. Freedom Press.

- ↑ Fred W. Thompson and Patrick Murfin (1976), IWW: Its First 70 Years, 1905-1975

- ↑ "The IWW, the state, and international affiliations". libcom.org. Retrieved 2016-12-16.

- ↑ "Estudios Interdisciplinarios de América Latina y el Caribe". www.tau.ac.il. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- ↑ "Organise Magazine issue 65". Anarchist Federation. 2005. Archived from the original on 2008-12-01. Retrieved 2009-09-29.

- 1 2 "Global anarcho-syndicalism 1939-99" (PDF). Selfed. 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-19. Retrieved 2009-09-29.

- ↑ G. Careri (1991), L'Unione Sindacale Italiana

- ↑ SAC had begun contesting municipal elections under the candidatures of Libertarian Municipal People

- ↑ "ASF-IWA – Anarcho-Syndicalist Federation". www.asf-iwa.org.au. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- ↑ SPIP, Design: Wolfgang (www.1-2-3-4.info) / Modified: Matthieu Marcillaud pour CMS. "CNT AIT TOULOUSE ANARCHOSYNDICALISME !". CNT AIT TOULOUSE ANARCHOSYNDICALISME !. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ "FAU and IWA – looking back to look ahead". From the Ashes. 2017-08-29. Retrieved 2023-12-10.

- ↑ Secretariat (2016-12-05). "Statement of the XXVI Congress". International Workers' Association. Archived from the original on 2016-12-07. Retrieved 2016-12-07.

- ↑ "Statement of the XXVI Congress - International Workers Association". iwa-ait.org. Archived from the original on 3 November 2017. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- ↑ The Belgrade Congress // iwa-ait.org, 11/12/2017.

- ↑ "Founding of a New International". 12 May 2018.

- ↑ "The XXVII Congress of the IWA". 2 January 2020. Retrieved 20 January 2020.