| Battle of Santa Cruz de Tenerife | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Anglo-Spanish War (1654–1660) | |||||||

Robert Blake's flagship George at the battle of Santa Cruz de Tenerife in 1657. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

2 galleons,[lower-alpha 1] 9 merchant ships,[lower-alpha 2] 5 other vessels, 1 castle and various shore gun emplacements | 23 warships[5] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

12 ships sunk, 5 captured[6][lower-alpha 3] 300 killed[8] |

1 ship severely damaged, 48 killed & 120 wounded[9][10] | ||||||

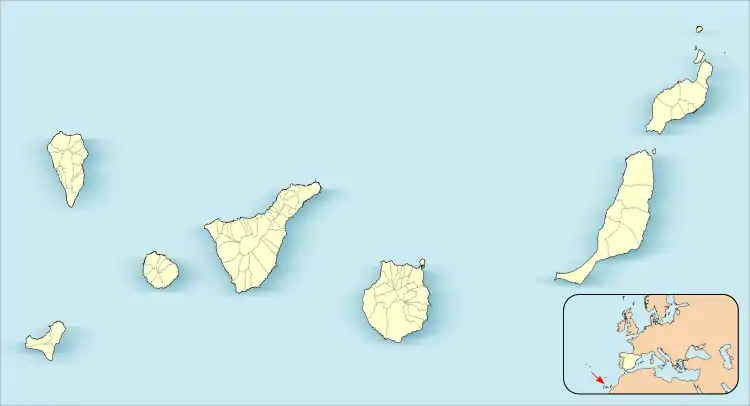

Location within Canary Islands  Battle of Santa Cruz de Tenerife (1657) (Africa) | |||||||

The Battle of Santa Cruz de Tenerife was a military operation in the Anglo-Spanish War (1654–60) which took place on 20 April 1657. An English fleet under Admiral Robert Blake penetrated the heavily defended harbour at Santa Cruz de Tenerife in the Spanish Canary Islands and attacked their treasure fleet. The treasure had already been landed and was safe but the English engaged the harbour forts and the Spanish ships, many of which were scuttled and the remainder burnt. Having achieved his aim, Blake withdrew without losing any ships.[11]

Background

England, ruled at the time by the Protectorate of Oliver Cromwell, decided to support France in its war with the Spanish Empire in 1654. This intervention was mostly motivated by hopes to profit from the war through raids on Spanish possessions in the West Indies. War was openly declared in October 1655 and endorsed when the Second Protectorate Parliament assembled the following year.[12] An English attempt to capture the Spanish colony of Santo Domingo failed, however, whereupon the English shifted their attention to Europe.[13] One of the prime enterprises became the blockade of Cadiz,[14] which had not previously been attempted on such a scale. Robert Blake was to be in charge and also was to come up with methods that he had used in his previous encounters with the Dutch and Barbary pirates.

Blake kept the fleet at sea throughout an entire winter in order to maintain the blockade. During this period a Spanish convoy was destroyed by one of Blake's captains, Richard Stayner.[15] A further six ships were sent from England as reinforcements towards the end of 1656, including George, which became Blake's flagship. In February 1657, Blake received intelligence that the convoy from Mexico was on its way across the Atlantic. Although his captains wanted to search for the Spanish galleons immediately, Blake refused to divide his forces and waited until victualling ships from England arrived to re-provision his fleet at the end of March. After this Blake (with only two ships to watch Cadiz), sailed from Cadiz Bay on 13 April 1657 to attack the plate fleet, which had docked at Santa Cruz de Tenerife in the Canary Islands to await an escort to Spain.[16]

Blake's fleet arrived off Santa Cruz on 19 April. Santa Cruz lies in a deeply indented bay and the harbour was defended by a castle, Castle of San Cristóbal (Santa Cruz de Tenerife), armed with forty guns and a number of smaller forts connected by a triple line of breastworks to shelter musketeers. In an operation similar to the raid on the Barbary pirates of Porto Farina in Tunisia in 1655, Blake planned to send twelve frigates under the command of Rear-Admiral Stayner in Speaker into the harbour to attack the galleons while he followed in George with the rest of the fleet to bombard the shore batteries.[17]

Battle

The attack began at 9:00 am on 20 April (of the Julian calendar still used in England by then; 30 April of the Gregorian calendar). Stayner's division manoeuvred alongside the Spanish ships, which protected the English ships to some extent from the guns of the castle and forts. No shot was fired from the English ships until they had moved into position and dropped anchor. While the frigates attacked the galleons, Blake's heavier warships sailed into the harbour to bombard the shore defences. Blake ordered that no prizes were to be taken; the Spanish fleet was to be utterly destroyed.[18] Most of the Spanish fleet, made up of smaller armed merchantmen, were quickly silenced by the superior gunnery of Stayner's warships. The two galleons fought on for several hours. Blake's division cleared the breastworks and smaller forts; smoke from the gunfire and burning ships worked to the advantage of the English by obscuring their ships from the Spanish batteries.[18]

Around noon, the flagship of the Spanish admiral, Don Diego de Egues, caught fire; shortly afterwards she was destroyed when her powder magazine exploded. English sailors took to boats to board Spanish ships and set them on fire. By 3:00 pm, all sixteen Spanish ships in the harbour were sunk, ablaze or had surrendered. According to other reports, twelve Spanish merchants survived the attack.[19] Contrary to orders, Swiftsure and four other frigates each took a surrendered ship as a prize and attempted to tow them out of the harbour. Blake sent peremptory orders that the prizes were to be burnt. He had to repeat his order three times before the reluctant captains obeyed.[10][20]

Having achieved its objective of destroying the Spanish vessels, the English fleet was faced with the hazardous task of withdrawing from Santa Cruz harbour under continuing fire from the forts. According to accounts the wind suddenly shifted from the north-east to the south-west at exactly the right moment to carry Blake's ships out of the harbour;[5][9] however, this story is probably based upon a misunderstanding of a report pertaining to general weather conditions on the voyage as a whole.[10] The English fleet worked its way back out to the open sea by warping out, or hauling on anchor ropes, a tactic Blake had introduced during the raid on Porto Farina. Speaker, which was the first ship to enter the harbour and last to leave, had been badly damaged, but no English ships were lost in the battle.[21]

Aftermath

The Spanish treasure from Mexico had been unloaded and secured ashore.[2][22] Blake was unable to seize it but it was also temporarily unavailable to the government in Madrid. According to historian John Barratt, the battle was a major victory and one of Blake's greatest exploits; he had penetrated a heavily defended harbour, burnt twelve Spanish ships and captured another five which were later destroyed.[1] Blake's force had suffered no more than 48 men killed and 120 wounded.[2]

News of the battle reached England the following month. It was inaccurately presented as a victory over 16 Spanish galleons.[19] On 28 May, Parliament voted to reward Blake with a jewel worth £500, which was equivalent to the reward voted to General Thomas Fairfax for his victory at the Battle of Naseby in 1645. Stayner was knighted by Oliver Cromwell.[23] Blake received orders to return home in June. He made one further voyage to Salé in Morocco, where he succeeded in concluding a treaty to secure the release of English slaves. He returned to Cadiz in mid-July and handed command of the fleet to his flag captain, John Stoakes. Leaving nineteen ships to maintain the blockade, Blake sailed for England with eleven ships, most in need of repair. However, Blake's health was in terminal decline. Worn out by his years of campaigning, he died aboard his flagship the George on 7 August 1657 as his fleet approached Plymouth Sound.[22]

The victory boosted the image of Cromwell's navy throughout Europe. Some of the Santa Cruz plate was captured when a hired Dutch ship was seized as it attempted to break the blockade of Cadiz.[24] Eventually, Egües and Centeno transported the treasure to Spain on 28 March 1658 (Gregorian calendar).[25] King Philip congratulated them for what was perceived by Spain as a victory (the safe delivery of the treasure) and awarded them rents of 2,000 and 1,500 ducats respectively.[26]

Ships involved

Blake's fleet comprised 22 vessels:[27]

The Spanish fleet comprised two war vessels:

- Jesús María, under D. Diego de Egües

- Concepción, under D. José Centeno

See also

Notes

- ↑ They were Jesús María, under D. Diego de Egues, and Concepción, under D. José Centeno.[4]

- ↑ They were Nuestra Señora de los Reyes, Capt. Roque Galindo; San Juan Colorado, Capt. Sebastián Martínez; Santo Cristo de Buen Viaje, Capt. Pedro de Arana; Campechano grande, Capt. Pedro de Urguía; Campechano chico, Capt. Miguel de Elizondo; Vizcaína, Capt. Cristóbal de Aguilar; Sacramento, Capt. Francisco de Villegas; Nuestra Señora de la Soledad, Capt. Istueta; and a patache under Pedro de Orihuela.[4]

- ↑ 2 galleons scuttled, 9 merchant ships scuttled[7]

References

- 1 2 Barratt (2016), p. 176.

- 1 2 3 Powell (1972), pp. 311–313.

- ↑ Grolier (1990), p. 325.

- 1 2 Fernández Duro (1900), p. 25.

- 1 2 Clowes (1898), p. 215.

- ↑ Barratt (2016), p. 5.

- ↑ Fernández Duro (1900), pp. 24–28.

- ↑ de Barrionuevo (1893), pp. 285–287.

- 1 2 Allen (1852), p. 52.

- 1 2 3 Barratt (2006), p. 182.

- ↑ Manganiello (2004), p. 481.

- ↑ Barratt (2016), pp. 6–8.

- ↑ Barratt (2016), pp. 8, 9.

- ↑ Barratt (2016), p. 8.

- ↑ Barratt (2016), p. 9.

- ↑ Barratt (2016), pp. 9, 10.

- ↑ Anderson (1952), p. 145.

- 1 2 Barratt (2006), p. 181.

- 1 2 Olaya, Vicente G. (28 September 2019). "El 'Google Maps' del XVII que revela la verdad de la batalla de Santa Cruz". El País.

- ↑ Lavery (2003), p. 159.

- ↑ Powell (1972), p. 309.

- 1 2 Barratt (2016), p. 10.

- ↑ Barratt (2006), p. 183.

- ↑ Barratt (2016), p. 177.

- ↑ Cesáreo Fernández Duro: Bosquejo biográfico del almirante D. Diego de Egües y Beaumont (1892), pp. 61-62.

- ↑ Fernández Duro (1900), pp. 56–58.

- ↑ Thomas, David (17 December 1998). Battles and Honours of the Royal Navy. Pen and Sword. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-85052-623-3.

References

- Anderson, R. C. (1952). Naval Wars in the Levant 1559–1853. Princeton: Princeton University Press. OCLC 1015099422.

- Allen, Joseph (1852). Battles of the British Navy (Volume: 1). London: H. G. Bohn. ISBN 1-4588-1112-3.

- Barratt, John (2006). Cromwell's Wars at Sea. Barnsley. ISBN 1-84415-459-9.

- Barratt, John (2016). 'Better Begging than Fighting': The Royalist Army in Exile in the War against Cromwell 1656–1660. Solihull: Helion & Company Limited. ISBN 978-1-910777-72-5.

- de Barrionuevo, Jerónimo (1893). Avisos de D. Jerónimo de Barrionuevo (1654–1658), Vol. III (in Spanish). Madrid: Tello.

- Capp, Bernard (1989). Cromwell's Navy: The Fleet And the English Revolution, 1648–1660. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-820115-X.

- Clowes, Sir William Laird (1898). The Royal Navy: a History from the Earliest Times to the Present, Vol. II. London: Sampson Low, Marston and Company.

- Corbett, Sir Julian Stafford (1904). England in the Mediterranean 1603–1713, Vol. I. London: Longmans, Green, and Co.

- Fernández Duro, Cesáreo (1900). Armada Española desde la unión de los reinos de Castilla y Aragón vol. V. Madrid: Sucesores de Rivadeneyra.

- Firth, C.H. (1909). The Last Years of the Protectorate, Vol. I. London: Longmans, Green, and Co.

- Grolier (1990). Academic American Encyclopedia, Volume 3. Grolier Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7172-2029-8.

- Lavery, Brian (2003). The Ship of the Line – Vol. 1: The Development of the Battlefleet 1650–1850. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-252-8.

- Manganiello, Stephen C (2004). The Concise Encyclopedia of the Revolutions and Wars of England, Scotland, and Ireland, 1639-1660. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-5100-9.

- Powell, John Rowland (1972). Robert Blake: General-At-Sea. Collins. ISBN 0-00-211726-6.