| Siege of Dunkirk | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Franco-Spanish War and Anglo-Spanish War | |||||||

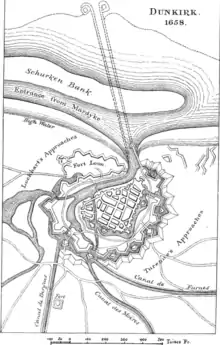

Map showing the Siege of Dunkirk and the Battle of the Dunes with the blockade of the English fleet in 1658 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

12,000 infantry 8,000 cavalry 18 warships |

2,200 infantry 700-800 cavalry | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,600-1,700[1] | |||||||

The siege of Dunkirk in 1658 was a military operation by the allied forces of France and Commonwealth England intended to take the fortified port city of Dunkirk, Spain's greatest privateer base, from the Spanish and their confederates: the English royalists and French Fronduers. Dunkirk (Dutch for 'Church in the dunes') was a strategic port on the southern coast of the English Channel in the Spanish Netherlands that had often been a point of contention previously and had changed hands a number of times. Privateers operating out of Dunkirk and other ports had cost England some 1,500 to 2,000 merchant ships in the past year.[2] The French and their English Commonwealth allies were commanded by Marshal of France Turenne. The siege would last a month and featured numerous sorties by the garrison and a determined relief attempt by the Spanish army under the command of Don Juan of Austria and his confederate English royalists under Duke of York and rebels of the French Fronde under the Great Condé that resulted in the battle of the Dunes.

Prelude

The French, in 1657, completed an alliance with the Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell, in which the English Commonwealth would join in the war against Spain and supply troops and ships for a campaign in the Spanish Netherlands. In return, Cromwell made the support of a fleet and 6,000 soldiers conditional on the transfer of Dunkirk to the English once it had been taken. The treaty was renewed in 1658 and encouraged by the promised additions the French were early into the field capturing a contingent of Spanish troops in Cassel, marching by way of Bergues on Dunkirk.

Turenne, with some 7,000 men was impeded by the heavy seasonal rains and by the opening of the sluices by his opponents which inundated all the low-lying ground in the area. He had been advised that it would be impossible to bring artillery with him under these conditions, but he persisted and succeeded.[3] Though often marching and wading through deep water holding their arms over their heads, French morale remained high and roads were made for their baggage and artillery. When Turenne reached the road at the dike at Bergues the Spanish were caught by surprise as they had assumed Turenne would make for Cambrai. The Spanish troops in the area, now under the command of the Marquis of Lede, acting as governor of Dunkirk during the siege, fell back into Dunkirk, raising the strength of the garrison to about 2,200 foot and 700 - 800 horse.[4] The Duke of York was ordered with his English regiments along with other troops in the nearby areas to march and throw themselves into Dunkirk, but they arrived too late and James found Dunkirk already invested and fell back.[5]

Siege

Turenne began the investment of Dunkirk on 25 May and reinforcements arrived in short order so that the French along with their English allies were now some 20,000 strong. Turenne quickly seized the outlying forts and immediately threw up lines of circumvallation and contravallation which on the east and west rested on the sea. The English fleet of 18 sail under the command of Mountague completed the blockade on the sea side. The surprised Spanish were unable to get any reinforcements into Dunkirk before the blockade and the Condé and Don Juan began hastily assembling their forces at Ypres to attempt the relief of Dunkirk. For the French, landing the supplies was difficult as the shores were obstructed with booms and chains but most supplies were brought by boat from Calais. To ensure his communications between the parts of his lines he had bridges built over the inundations and had his supplies brought in by sea. Young King Louis XIV and Cardinal Mazarin were personally involved nearby arranging for supplies and ammunition, first at Mardyke and then, at Turenne's urging, Calais. Trenches were opened on the Downs side of Dunkirk on the night of 4/5 June and finished with the arrival of more troops from France and the 6,000 man English contingent. The English under Lockhart made their approaches from the west side of Dunkirk and the French from the east with their line extended from the sea to the canal of Furnes. Turenne then posted the Lorraine regiment in the great fort between Bergues and Dunkirk. Marquis de Castelnau with his troops deployed west of the Bergues canal and linked up with the English.

A sortie was made by the all cavalry of the garrison the first night after the opening of the trenches against the French which was driven back. The next morning all the garrison cavalry with 20 guns on that side covering them made several attempts on the French lines. The French cavalry, in return, repulsed each advance although suffering some casualties from cannon fire as they pursued the Spanish back to the counterscarp.[6]

On the fourth day of the siege a high wind blew heavy sand into the faces of the French blinding them. The garrison sallied out under cover of the sand and filled in the point of the trench killing or wounding about 100 soldiers of the regiments of Picardy and Plessis. The wind and tide made the line of circumvallation difficult to maintain on the Downs side. The French put up a stockade of huge pilings but it was knocked down by strong tides. Afterwards the French cavalry kept watch on the shore and bomb chests were placed on the shore when the tide went out and removed each time it came in.[7] A day or two later the English stormed the pallisades several times but were unable to effect a lodgement and each time were thrown back with heavy losses. The French also made three or four attempts on their side without success.[8] On 13 June, the French took some advanced palisades on the glacis but could not make themselves masters of the counterscarp.

The Spanish and their allies, now clear about Turenne's intentions, assembled the confederate army at the end of May at Ypres.[5] The Spanish relief army marched by way of Nieuport and Furnes arriving on the dunes about 3 miles from Dunkirk on 13 June. On that morning the Spanish relief army was observed marching along the coast from the east.

During the day the Spanish relief army and their confederates having arrived, camped on the sand-hill (dunes) of the Downs[4] on the east side of the siege lines. In their haste to get to Dunkirk they let their artillery fall more than a day's march behind, Don Juan trusting that Turenne would not move against them before it arrived. Both Condé and the Duke of York both warned Don Juan that Turenne would not hesitate to attack, but Don Juan dismissed the possibility. Turenne immediately advanced on the relief force and there were some skirmishes on the night of the 13 June, but the Marshal was determined to attack on the morning of the 14th.

The Battle of the Dunes began around 10 in the morning. The Spanish army of about 6,000 foot and 8,000 horse[9] with its right on the sea across the sand-hills to the canal of Furnes on their left advanced against a French army of some 6,000 foot and 8,000 horse[9] and 10 cannons, deployed with their left on the sea and their right on the canal. The battle lasted for about two hours and by noon Turenne had a complete victory[10] that ended with the rout of the Spanish forces, who lost about 1,200 killed, 3,000 wounded[11] and some 5,000 captured while the French lost only about 400, most of them English.

The French pursuit lasted until nightfall. On the Dunes, one royalist regiment continued to stand its ground and fight until a couple of French officers under a truce pointed out that the rest of their army had retreated. Most of the French Frondeurs, led by Condé, withdrew in good order. While the battle was being fought, the garrison of Dunkirk sallied out and burnt the English camp destroying or carry off all their supplies.[12]

With the defeat of the relief army the fall of Dunkirk was just a matter of time. The French soon carried the demi-lune on their side of the town and the English made a lodgement on Fort Leon. Three days after the battle the Marquis de Crequis leading the Turenne regiment made a lodgement on the counterscarp, suffering heavy casualties. The English, although making determined efforts, could not make a lodgement until the counterscarp was abandoned. The Marquis of Lede was again summoned to surrender but replied defiantly with a fusillade. Shortly afterwards the Marquis was mortally wounded and died 5 or 6 days later. With the loss of its stubborn and active governor, no hope of relief, and the French now lodged at the foot of the last work,[1] Dunkirk surrendered on 25 June after a siege of 22 days from the opening of the trenches. The remaining 1800 troops of the garrison marched out the next day while Lockhart entered with two English regiments. Louis XIV, himself, placed the keys of Dunkirk into the hands of the new governor of Dunkirk, Sir William Lockhart on 26 June 1658.[12]

Aftermath

After the capture of Dunkirk and his victory in the battle of the Dunes Turenne advanced, capturing a series of towns and fortresses including Veurne, Diksmuide, Gravelines, Ypres and Oudenarde.[13] The victory at the battle of the Dunes, the capture of Dunkirk and their consequences would lead to the end of Franco-Spanish War with the signing of Treaty of the Pyrenees. By this treaty France gained Roussillon and Perpignan, Montmédy and other parts of Luxembourg, Artois and other towns in Flanders, including Arras, Béthune, Gravelines and Thionville, and a new border with Spain was fixed at the Pyrenees.[14] Spain was forced to recognise and confirm all of the French gains at the Peace of Westphalia.[14]

The defeats the Spanish suffered at the battle and the siege ended the immediate prospect of the intended Royalist expedition to England. Cardinal Mazarin honoured the terms of the treaty with Oliver Cromwell and handed the port over to the Commonwealth in exchange for Mardyck captured earlier by the French in 1658 and held by the English. Cromwell died two months after the battle of the Dunes and the protectorship passed to his son, Richard, but ended 9 months later and the Commonwealth fell into confusion whereupon Charles II returned to the throne in May 1660. While the French received all of Artois, England had eliminated the greatest Spanish privateering base[15] and the number of captured English merchant ships carried into Flemish ports was halved in 1657–58.[16] Charles would sell Dunkirk back to the French in 1662 for £320,000.[17]

Notes

- 1 2 Ramsay 1735, p. 188.

- ↑ Rodger 2004, p. 28.

- ↑ Longueville 1907, p. 258.

- 1 2 Ramsay 1735, p. 178.

- 1 2 Hamilton 1874, p. 23.

- ↑ Ramsay 1735, p. 180.

- ↑ Ramsay 1735, pp. 179–180.

- ↑ Ramsay 1735, p. 181.

- 1 2 Hamilton 1874, p. 24.

- ↑ Tucker 2010, p. 214.

- ↑ Clodfelter 2017, p. 42.

- 1 2 Waylen 1880, p. 214.

- ↑ Longueville 1907, p. 267.

- 1 2 Maland 1991, p. 227.

- ↑ Rodger 2004, p. 29.

- ↑ Capp 1989, p. 103.

- ↑ Grant 2010, p. 131 (map note).

References

- Capp, B.S. (1989), Cromwell's navy: the fleet and the English Revolution, 1648-1660, USA: Oxford University Press, ISBN 019820115X

- Clodfelter, Micheal (2017), Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492-2015 (4th ed.), Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, ISBN 9780786474707

- Grant, R G (2010), Battle at Sea: 3000 years of naval warfare, Dorling Kindersley, p. 131, ISBN 9781405335058

- Hamilton, Sir Frederick William (1874), The Origin and History of the First or Grenadier Guards, vol. I, London: John Murray

- Hozier, Sir Henry Montague (1885), Turenne, London: Chapman & Hall

- Longueville, Thomas (1907), Marshall Turenne, London: Longmans, Green, & Co., pp. 252–267

- Maland, David M.A. (1991), Europe in the Seventeenth Century (Second ed.), Macmillan, p. 227, ISBN 0-333-33574-0

- Ramsay, Andrew Michael (1735), The history of Henri de La Tour d'Auvergne, Viscount de Turenne, Marshal of France, vol. II, London, p. 184, 499–500. (This volume includes Memoirs of the Duke of York: First of the Civil Wars in France)

- Rodger, N.A.M. (2004), The Command Of The Ocean: A Naval History Of Britain, 1649-1815, Volume 2, London: W.W. Norton & Company, pp. 28–29, ISBN 0-393-06050-0

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2010), Battles That Changed History: An Encyclopedia of World Conflict, Santa Barbara: Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 978-1-59884-429-0

- Waylen, James (1880), The house of Cromwell and the story of Dunkirk, London: Chapman and Hall, Ltd., p. 198