| Battle of Stirling | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Scottish Civil War | |||||||

Stirling Castle | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

(under the overall command of the Earl of Lanark) |

(under the overall command of the Marquess of Argyll) | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 10,000 | 1,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown |

200 killed[1] 400 captured (according to Keltie)[2] 700 killed (according to Wheeler)[3] | ||||||

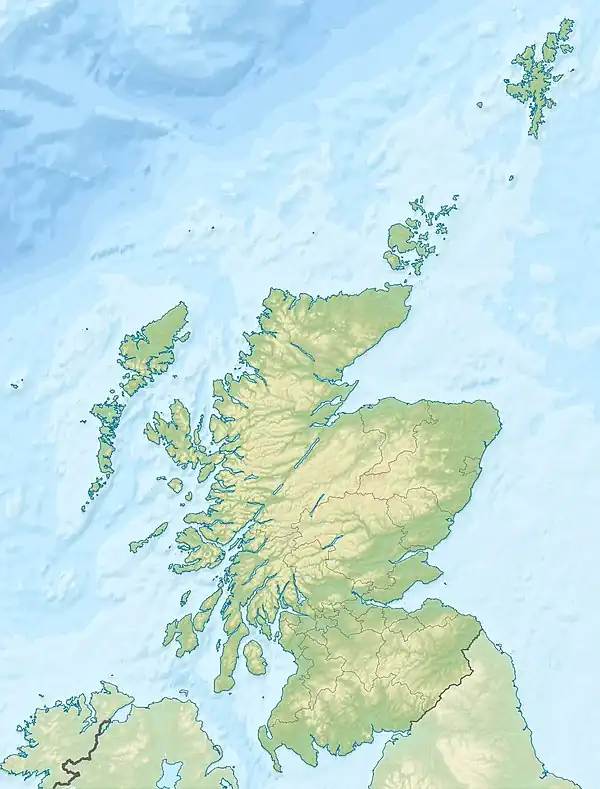

Location within Scotland | |||||||

The second Battle of Stirling was fought on 12 September 1648 during the Scottish Civil War of the 17th century. The battle was fought between the Engagers who were a faction of the Scottish Covenanters under the command of George Munro, 1st of Newmore and who had made "The Engagement" with Charles I of England in December 1647, against the Kirk Party who were a radical Presbyterian faction of the Scottish Covenanters who were under the command of Archibald Campbell, 1st Marquess of Argyll.

Background

The Battle of Stirling in 1648 was part of the War of the Three Kingdoms. By this time, the Presbyterian Covenanter movement had defeated the Scottish Royalists, who favoured unconditional loyalty to King Charles I.

The Independent party in the English Parliament and the English New Model Army posed a threat to the Solemn League and Covenant and the aspirations of the Scots and the English Presbyterians to secure a Presbyterian church north and south of the border.[4]

One faction of the Covenanters entered into an engagement with Charles I who agreed to sign the National Covenant in exchange for Scottish help to him and the English Presbyterians against the English Independents in the Second English Civil War. Those that supported this engagement between the King became known as Engagers.[5][6]

The Engagers army under the command of the Duke of Hamilton was defeated by the New Model Army under the command of Oliver Cromwell at the Battle of Preston (1648).[7]

Those Covenanters who had opposed the Engagement, seized the opportunity presented by the loss of credibility suffered by the Engagers and launched the Whiggamore Raid which led to their successful capture of Edinburgh.[8] This initiated the short civil war between the Engagers and their opponents known as the Kirk party.[9]

The Earl of Lanark, younger brother of the Duke of Hamilton, had been left to defend Scotland against Archibald Campbell, 1st Marquess of Argyll, a covenanter and a leading member of the Kirk party who was now in open rebellion against the Scottish parliament, over their Engagement with King Charles.[10]

The nucleus of the Marquis of Argyll's force amounted to about 300 men, who were joined by another 400 on the way to Stirling. He was also joined by a further 300 militiamen when he arrived in Stirling on the morning of September 12, 1648. His men were assigned to guard various areas of the town and his main force joined him to dine at the Earl of Mar's residence.[2]

The battle

Argyll had barely begun his meal when the Earl of Lanark's advance forces, commanded by Sir George Munro, 1st of Newmore, a Highlander, came into the Deer Park (now the King's Park).[11][12] Argyll then mounted his horse and galloped over Stirling Bridge to seek safety.[11][12] While making his escape he came under fire from Stirling Castle which had not yet surrendered to Argyll and was still flying the King's colours.[2]

Having learned that Argyll was in Stirling, Sir George Munro moved in on his own initiative to try to capture one of Argyll's commanders, a MacKenzie who was his hated enemy, and had actually succeeded in entering Stirling before any of Argyll's commanders were aware of his presence.[2] Munro even personally kicked down a postern door to chase out Argyll's men.[1][13]

The battle surprised the Marquis of Argyll's men, who broke after some initial resistance, losing about 200 killed,[1] and a further 400 taken prisoner. Many more were killed trying to escape and some even drowned trying to swim across the River Forth to safety.[14][15] Among the dead on Argyll's side were William Campbell of Glenfalloch,[16] and Sir Colin Campbell of Ardkinglas, both killed in action. Dougal MacTavish who was a younger son of John MacTavish, 12th chief of Clan MacTavish, who in turn were a sept of the Clan Campbell, was also killed during the battle.[17] The chief of Clan MacTavish having lost most of his arms in the battle (sword and musket), the Marquess of Argyll, chief of Clan Campbell, provided him with new weapons.[17]

Outside Stirling the Earl of Lanark had a force of 4,000 horse and 6,000 foot. Argyll's General David Leslie commanded 3,000 horse and 8,000 foot also outside Stirling. It is interesting to speculate what sort of battle would have taken place the next day had it not been for Munro's initiative on the morning of 12 September 1648.[2]

Munro urged Lanark to continue fighting after the battle and attack David Leslie's forces, but he was overruled and negotiations for peace began on 15 September. Both sides agreed to disband their forces by 29 September 1648.[2]

Aftermath

Shortly after this battle the armies of the Earl of Lanark and the Marquess of Argyll, which was commanded by David Leslie, made peace and joined forces. On 27 September 1648 the Treaty of Stirling was agreed and led to the end of Engager dominance of Scotland.[18]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Wishart, George; Murdoch, Alexander Drimmie; Simpson, Harry Fife Morland (1893). "Deeds of Montrose". The Memoirs of James, Marquis of Montrose, 1639-1650. London and New York City: Longmans, Green, and Co. p. 219-220.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Keltie, John S. F.S.A. Scot (1885). History of the Scottish Highlands, Highland Clans and Scottish Regiments. Vol. 1. Edinburgh: T.C. Jack. p. 258.

- ↑ Wheeler, James Scott (2002). The Irish and British Wars 1637 - 1654. p. 198. ISBN 0-415221-32-3.

- ↑ Wishart, George; Murdoch, Alexander Drimmie; Simpson, Harry Fife Morland (1893). "Deeds of Montrose". The Memoirs of James, Marquis of Montrose, 1639-1650. London and New York City: Longmans, Green, and Co. p. 205-207.

- ↑ Manganiello, Stephen C (2004). The Concise Encyclopedia of the Revolutions and Wars of England, Scotland, and Ireland, 1639-1660. Scarecrow Press. pp. 185–188. ISBN 9780810851009.

- ↑ Ashley, Maurice (1992). The Battle of Naseby and the Fall of King Charles I. p. 129. ISBN 9780862996284.

- ↑ Manganiello, Stephen C (2004). The Concise Encyclopedia of the Revolutions and Wars of England, Scotland, and Ireland, 1639-1660. Scarecrow Press. pp. 441–442. ISBN 9780810851009.

- ↑ Manganiello, Stephen C (2004). The Concise Encyclopedia of the Revolutions and Wars of England, Scotland, and Ireland, 1639-1660. Scarecrow Press. p. 576. ISBN 9780810851009.

- ↑ Manganiello, Stephen C (2004). pp. 40, 347 and 576.

- ↑ Manganiello, Stephen C (2004). The Concise Encyclopedia of the Revolutions and Wars of England, Scotland, and Ireland, 1639-1660. Scarecrow Press. pp. 237–238. ISBN 9780810851009.

- 1 2 Ronald, James (1899). Landmarks of Old Stirling. Vol. c.1. Stirling: E. Mackay. pp. 184-185.

- 1 2 Ronald, James (1899). Landmarks of Old Stirling. Vol. c.1. Stirling: E. Mackay. pp. 228-229.

- ↑ Reid, Stuart (1998). All the King's Armies: a military history of the English Civil War 1642-1651. p. 233. ISBN 1-862270-28-7.

- ↑ Drysdale, William (1904). Auld biggins of Stirling, its closes, wynds, and neebour villages. Stirling: E. Mackay. p. 58.

- ↑ Gordon, Robert (1813) [Printed from original manuscript 1580 - 1656 - with extension from 1630 to 1651 by Gilbert Gordon of Sallagh]. A Genealogical History of the Earldom of Sutherland. Edinburgh: Printed by George Ramsay and Co. for Archibald Constable and Company Edinburgh; and White, Cochrance and Co. London. p. 544.

- ↑ Tweed, John (1871). The house of Argyll and the collateral branches of the clan Campbell, from the year 420 to the present time. Glasgow: J. Tweed. p. 139.

- 1 2 Thompson, Patrick. L (2012). History of Clan MacTavish (PDF). p. 14.

Quoting: "In 1845 the Chief of Clan MacTavish, Sheriff Dugald MACTAVISH of Dunardry wrote "twenty one generations from father to son without an instance of collateral or female succession" National Library and Archives of Canada: Hargrave-MacTavish Papers, Letter by Sheriff Dugald MacTavish of Dunardry, dated Kilchrist, 18 Feb. 1845.

- ↑ Manganiello, Stephen C (2004). The concise encyclopedia of the revolutions and wars of England, Scotland, and Ireland, 1639–1660. Scarecrow Press. p. 576. ISBN 978-0-8108-5100-9.