| Battle of Tutrakan | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Dobruja Campaign of the Romanian Campaign of World War I | |||||||

"The Battle of Tutrakan" by Dimitar Giudzhenov | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

31 battalions: 55,000 |

19 battalions (initially): 39,000 36 battalions (end phase) 4 river monitors 8 gunboats | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Dead or wounded: 9,205[1] |

Dead or wounded: 7,500[2] Taken POW: 480 officers and 22,000–28,000 soldiers[3][4][5] | ||||||

The Battle of Turtucaia (Romanian: Bătălia de la Turtucaia; Bulgarian: Битка при Тутракан, Bitka pri Tutrakan), also known as Tutrakan Epopee (Bulgarian: Тутраканска епопея, Tutrakanska epopeya) in Bulgaria, was the opening battle of the first Central Powers offensive during the Romanian Campaign of World War I. The battle lasted for five days and ended with the capture of the fortress of Turtucaia (now Tutrakan) and the surrender of its Romanian defenders.

Background

By August 1916 the Central Powers found themselves in an increasingly difficult military situation – in the West the German offensive at Verdun had turned into a costly battle of attrition, in the East the Brusilov Offensive was crippling the Austro-Hungarian Army, and in the South the Italian Army was increasing the pressure on the Austro-Hungarians, while General Maurice Sarrail's Allied expeditionary force in northern Greece seemed poised for a major offensive against the Bulgarian Army.

The Romanian government asserted that the moment was right for it to fulfill the country's national ambitions by aligning itself with the Entente, and declared war on the Austro-Hungarian Empire on 27 August 1916. Three Romanian armies invaded Transylvania through the Carpathian Mountains, pushing back the much smaller Austro-Hungarian First Army. In a short time the Romanian forces occupied Orșova, Petroșani, and Brașov, and reached Sibiu on their way to the river Mureș, the main objective of the offensive.

In response the German Empire declared war on the Kingdom of Romania on 27 August, with the Kingdom of Bulgaria following suit on 1 September. On the next day the Bulgarian Third Army initiated the Central Powers' first major offensive of the campaign by invading Southern Dobruja.

Origins and state of the fortress

Tutrakan was originally a Roman fort. During the reign of Emperor Diocletian (284–305) it developed into one of the largest strongholds of the Danubian limes. In the 7th century it became part of the Bulgarian Empire, until the latter was subjugated by the Ottoman Empire in the late 14th century. When the Ottoman Empire entered its period of decline, it relied on the Danube as its main defensive barrier in the Balkans. The enormous width of the river, however, proved insufficient to defend against the armies of the Russian Empire, which crossed it several times in its lower stretch during the numerous Russo-Ottoman Wars. To counter this constant threat the Ottoman military created the fortified quadrilateral Ruse–Silistra–Varna–Shumen, hoping to prevent any invaders from crossing the Balkan Mountains and threatening Istanbul. Tutrakan was situated on the northern side of the quadrilateral, on a stretch where the Danube is narrow, across from the mouth of the navigable Argeș River. This made it an excellent spot for a crossing and prompted the Ottomans to fortify it with a large garrison.

With the liberation of Bulgaria after the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878), Tutrakan became an integral part of the country, but Bulgarian national ambitions were directed in general towards Macedonia and Thrace, and the defense of the Danube was largely neglected. As a result of the Second Balkan War, Tutrakan and the entire Southern Dobruja region were ceded to Romania in 1913, with the town being renamed to Turtucaia.

The Romanian General Staff immediately took measures to strengthen the defences of the town, designing it to serve as a bridgehead in the event of war with Bulgaria. Intensive construction work lasted for more than two years under the guidance of Belgian military engineers.[6] The surrounding terrain was favorable for a bridgehead, as the heights overlooking the town form a plateau 7 to 10 kilometres wide, rising as high as 113 meters over the Danube, and being surrounded by numerous wide ravines.[7]

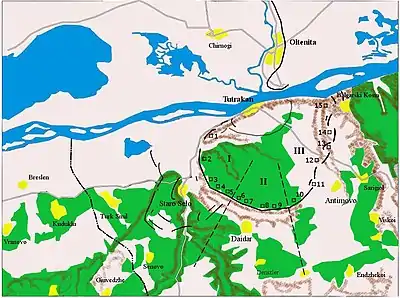

The basic defense consisted of three concentric lines of trenches anchored on the river. The most forward of these were small outposts designed for surveillance. To the west, around the village of Staro Selo, the outer fortifications were of a more extensive character.

The main defensive line was constructed on the very edge of the plateau in order to keep enemy artillery away from any bridge that could be built to Turtucaia. The line stretched for almost 30 kilometers and had as its heart fifteen "centers of resistance", forts numbered from one to 15 and bearing the names of local settlements - "Turtucaia", "Staro Selo", "Daidâr", "Sarsânlar" etc. Each of these incorporated two shelters for 50 to 70 soldiers, with roofs supported by iron rails or wooden boards, on top of which a two-meter layer of earth was laid. Their profile was low, rising only about 60 centimeters, thus ensuring reasonable protection against field artillery shells.[7] Spaced from 1.2 to 2.2 kilometers apart, the individual forts were linked by shallow trenches and machine gun nests, which were in turn connected via communication trenches to the rear of the main defensive line. The intervening spaces were further covered by rifle and machine gun positions in the flanks of the forts. The "centers of resistance" were well protected by barbed wire obstacles that reached a depth of 10 to 15 meters, but they were placed some 50 metres away from the firing line and thus could not be defended with hand grenades. A hundred meters in front of the main line the Romanians had built three rows of pitfalls and barbed wire that ran continuously from fort 15 to fort 3.[8] Most of the artillery was placed in the main defensive line, although several pieces, along with trenches and machine guns, were placed on the nearby islands of the Danube in order to support the Romanian Danube Flotilla, which was tasked with providing artillery cover on the western approaches to the fortress.[7]

Some four kilometers from the main defensive line and three kilometers from Turtucaia itself lay the secondary defensive line of the fortress. It consisted of a single line of trenches with few prepared machine gun nests or obstacles, and no artillery at all. With their attention focused almost entirely on the main defensive line, the Romanian command largely ignored this secondary line.

For command purposes the entire area of the fortress was divided into three sectors: I (west), II (south) and III (east), also named after local villages - Staro Selo, Daidâr, and Antimova. Each of them had its own commander.[6]

The garrison

The defense of the Danube and Dobruja frontiers was entrusted to the Romanian Third Army, under the command of General Mihail Aslan, who had his headquarters in Bucharest. The fortress of Turtucaia was commanded by the head of the Romanian 17th Infantry Division, General Constantin Teodorescu, who by the beginning of the conflict had the following forces at his disposal:

17th Infantry Division (Teodorescu)

- 18th Infantry Brigade

- 36th Infantry Regiment

- 76th Reserve Regiment

- 39th Infantry Brigade

- 40th Infantry Regiment

- 79th Reserve Regiment

- one company of border guards

- one cavalry squadron

- four militia battalions

- one pioneer company

Romanian battle strength stood at 19 battalions, with over 20,000 men and 66 machine guns. Only three of the battalions were of the standing army, with the rest drawn from the reserve. A valuable asset for the garrison was the assistance of the Romanian Danube Flotilla, consisting mainly of the 2nd Monitor Division: Brătianu, Kogălniceanu and Catargiu.[9]

General Teodorescu could rely on a large artillery park, consisting by the end of August of over 157 guns ranging in caliber from 7.5 to 21 centimeters; however, most of these were fixed guns that lacked modern, quick-firing capability.[3] The trench artillery consisted of numerous small-caliber turret guns, while the mobile horse-drawn artillery had 23 guns, only eight of them quick-firing.[10] In the Western Sector the troops benefited from the guns of the Danube Flotilla. Almost all of the artillery was deployed in the main defensive line, but the fixed artillery in particular was positioned in a way that made it difficult for all the guns to concentrate their fire on a single spot.[8] The cannon were distributed in equal quantities among the sectors, leaving no reserve at all. Compounding these difficulties was the fact that the guns, in most cases, were firing from platforms, which meant that their position could not be shifted.[8]

The garrison of Turtucaia was connected to Olteniţa, which lay across the Danube, by a submerged telephone cable, and to Third Army headquarters in Bucharest by a wireless telegraph station; however, it remained relatively isolated from the nearest Romanian units in Dobruja. The 9th division was almost 60 kilometres to the east in Silistra, while the 19th Division and 5th Cavalry brigade were 100 kilometres to the south-east, around Bazargic (now Dobrich).[6] The Romanian 16th, 20th, 18th Infantry and 1st Cavalry divisions were all on the left bank of the Danube and could be used to reinforce the fortress if needed.

In general, despite some of the defence's defects, the Romanian command was convinced of the strength of the fortress, and confident in its ability to hold out against major enemy attacks. It was often referred to as "the second Verdun", or "the Verdun of the East".[7] This comparison was not entirely without justification. Most of the major European fortresses had forts of the same type as the 15 around Turtucaia; e.g. Liège had 12, Przemyśl had 15 and Verdun itself had 23.[7]

The attackers

To protect their Danube frontier the Bulgarians had activated their Third Army as early as September 1915, giving its commander, Lieutenant General Stefan Toshev, almost a year to train and equip his troops. When Romanian intentions became clear in the middle of 1916, strengthening Third Army became a priority for the Bulgarian high command.

At the end of August the army was subordinated to Army Group Mackensen, under the overall command of Field Marshal August von Mackensen, who had transferred his headquarters from the Macedonian front for the specific purpose of coordinating the offensive against Romania.[6] By 1 September the Third Army had concentrated 62 infantry battalions, 55 artillery batteries and 23 cavalry squadrons on the Dobruja frontier.[11] For operations against the Turtucaia fortress General Toshev planned to use the left wing of his army, composed of the following:

4th Preslav Infantry Division (Kiselov)

- 1st Infantry Brigade (Ikonomov)

- 7th Preslav Infantry Regiment(4)

- 31st Varna Infantry Regiment(4)

- 3rd Infantry Brigade (Kmetov)

- 19th Shumen Infantry Regiment(4)

- 48th Infantry Regiment(3)

- 47th Infantry Regiment(2)

- 4th Artillery Brigade (Kukureshkov)

- 15th Artillery Regiment(6)

- 5th Artillery Regiment(6)

- 2nd Heavy Artillery Regiment(2)

- 3rd Howitzer Regiment(2)

- 4th Pioneer Battalion

1/1st Infantry Brigade (Nedialkov)

- 1st Sofia Infantry Regiment(4)

- 6th Turnovo Infantry Regiment(4)

- 4th Artillery Regiment(6)

- 1st Howitzer Regiment(3)

- 1st Pioneer Battalion

German-Bulgarian Detachment (von Hammerstein from 4 September)

- 1/21st German Infantry Battalion

- 5th March Regiment(3)

- 5th Opalchenie Regiment(2)

- 6th Uhlan Regiment

- 105th German Heavy Howitzer Battery

- 1/201st German Field Battery

- two not quick firing 8.7 cm batteries

The battle strength of these forces consisted of 31 infantry and reserve battalions, 29 batteries and 7 squadrons or a total of around 55,000 men with 132 artillery pieces and 53 machine guns.[12][13] This ensured the initial numerical superiority of the attackers both in men and firepower, but most of the Bulgarian units, with the notable exception of the 1st Brigade of the 1st Sofia Infantry Division, did not have direct combat experience, as they did not take part in the Serbian Campaign. They had, however, profited from recent improvements in the Bulgarian Army, including the addition of more machine gun companies and heavy artillery as well as improved communications and logistical support.[6]

The Bulgarian and German artillery consisted of modern quick-firing howitzer, field or long guns that varied in caliber from 7.5 to 15 centimeters. Unlike the Romanians, however, the Bulgarians and Germans could not rely on supporting fire from their allied Danube monitors because the Austro-Hungarian Danube Flotilla had been bottled up in the Persina channel by passive and active Romanian measures.[6] For reconnaissance, observation and directing of the artillery fire, the invading forces had also deployed a balloon and several aircraft.

Initially general Toshev retained direct control over the left wing of his army, but as the battle progressed it was realized that a common command on the battlefield itself was needed, and general Panteley Kiselov, the commander of the 4th Preslav Division, was placed in charge of all forces operating against Turtucaia. While retaining the control of his division he did not receive any additional staff, which created problems with the coordination of the forces. Nonetheless general Kiselov and his chief of staff Lieutenant Colonel Stefan Noykov were rated excellent officers by the Germans and represented the top divisional leadership in the Third Army.[6]

The Bulgarian government took great care in assisting the preparations of the operations and declared war on Romania on 1 September—five days after the German government, a move that had initially caused a great deal of concern in the German high command.

Strategic planning

The Bulgarian plan

On 28 August field marshal Mackensen issued his first directive to the Bulgarian Third Army, ordering it to prepare for a decisive advance aimed at seizing the vital crossing points on the Danube in Southern Dobruja. This envisaged the simultaneous capture of both Turtucaia and Silistra by the 4th and 1st divisions.[14] Though general Toshev began deploying his forces as required by the field marshal, he was deeply opposed to dividing them in two and attacking both fortresses. On 31 August the two men met at the Gorna Oryahovitsa train station to exchange thoughts on the operation. Relying on his better intelligence on Romanian forces in Dobruja and the state of their fortifications, the general managed to convince the field marshal to prioritize the capture of Turtucaia over that of Silistra, and concentrate all available forces for that purpose alone. On the same day Toshev presented a detailed plan for the assault, according to which the army would advance on 2 September with its left wing against the bridgehead while the 3/1 Infantry Brigade moved in the direction of Silistra to cover its flank. The right wing of the army, consisting of the 6th Infantry Division and the Varna Garrison, was to advance against Bazargic and Balcic with the 1st Cavalry Division linking it to the left wing. On the next day von Mackensen approved the plan with minor adjustments, such as requiring that the 2/1 Infantry Brigade be kept in reserve for the defense of the right flank of the forces attacking Turtucaia. After receiving the field marshal's sanction, the staff of Third Army moved to Razgrad, from where it began coordinating final preparations for the offensive.[14]

On 1 September von Mackensen received a telegram from the new Chief of the German General Staff von Hindenburg informing him that German and Austro-Hungarian build up in Transylvania would be completed no sooner than the second half of September while the forces that were already deployed would be able only to defend their positions against the advancing Romanians. Von Hindenburg and the Bulgarian commander in chief general Zhekov then both confirmed the orders of the Bulgarian Third Army to advance into Dobruja in order to draw and defeat as many Romanian and Russian forces as possible, stressing the importance of a rapid success for the entire Romanian Campaign.[14]

The Romanian plan

The Romanian plan, or the so-called Hypothesis Z, required most of the country's forces to invade Transylvania, while its almost 150,000-strong Third Army assumed a defensive stance along the Danube and Dobruja frontiers for ten days. Thereafter, the southern forces would attack from the Dobruja into Bulgaria with the expected assistance of general Andrei Zayonchkovski's Russian Army Corps and establish a tenable position on the Ruse–Shumen–Varna line, thus providing the northern armies operational freedom.[13]

The Russians crossed the Danube on schedule and concentrated around Cobadin. On 31 August General Aslan subordinated the 19th Romanian Infantry Division, which was deployed in Bazargic, and created the Eastern Operations Group under the command of general Zayonchkovski. The Romanians decided to defend both Turtucaia and Silistra along with the entire Dobruja frontier in order to ensure themselves appropriate conditions for their future drive into Bulgaria. General Aslan realized that his forces were too dispersed for this task and ordered the Russians to deploy closer to the fortresses, but general Zayonchkovski thought that he should concentrate his corps first at Bazargic and then if the conditions allowed move towards Turtucaia and Silistra. Thus valuable time was lost in solving this question and the Russian corps began moving south on 3 September.[15]

The battle

Encirclement of Turtucaia (2–4 September)

Early on the morning of 2 September the Bulgarian Third Army crossed the Romanian border along its entire length, and its left wing began closing on the fortress. Colonel Kaufman's German-Bulgarian detachment advanced against Sector I (West) of the fortress, pushing back the weak Romanian vanguards and taking up positions to the east of the village of Turcsmil, where they were halted by strong Romanian artillery fire from the Danube Flotilla and batteries on the river islands. The 4th Preslav Division, delivering the main attack in Sector II (South), quickly overran the Romanian outposts, the Romanian soldiers retreating so fast that none were captured.[6] The division advanced between 15 and 23 km and came within 2.7 kilometers of the main defensive line, while shortening its front from 20 to 10 kilometers.[16] Meanwhile, in Sector III (East) the Bulgarian 1/1 Infantry Brigade met no resistance at all, as the Romanian commander had pulled his troops behind the main defensive line before coming under attack.[6]

By the evening of the first day the Romanians had abandoned almost their entire preliminary line of defense in favor of the main (second) defensive line. From there they put up continuous rifle fire, supported by occasional artillery fire, throughout the night of 2/3 September - perhaps belying disorganization and nervousness,[6] as the Bulgarian units were, as yet, well out of range.[17] The Romanian command was slow to react to the developing situation, with General Aslan remaining in Bucharest. He ordered general Zayonchkovski to approach the Bulgarian frontier with his forces, but the order was only carried out after extensive delays. Attempts were also made to send reinforcements from the reserves around the capital, but these too were delayed due to the general confusion and congestion accompanying the Romanian mobilization.[6]

On 3 September the Bulgarians began consolidating their positions. To do this more effectively the German-Bulgarian detachment was ordered to take height 131, west of Staro Selo, where it would secure a staging area for the assault on the Romanian forts in Sector I (West). The defenders here were relatively well entrenched and protected by rows of barbed wire, while the attackers had to advance through an open field with their flanks exposed to fire from the Romanian monitors and some of the trenches.[18] Romanian positions further south, around the village of Senovo, were fronted by low hills that could provide cover for advancing infantry, which prompted Colonel Kaufman to divide his detachment into three columns (commanded by Colonel Vlahov, Major von Hamerstein, and Colonel Drazhkov) and use one to attack towards Senovo while the other two supported it. Advancing at about 5 am, Colonel Vlahov's force initially met little resistance; however, Romanian fire gradually intensified, and the Bulgarian column was exposed to flanking fire from the main defensive line. Some of the soldiers reached the barbed wire, but were unable to get through it. At noon the units were ordered to dig in on the positions they had reached. Colonel Vlahov's request for reinforcement was denied. Romanian counterattacks forced the Colonel to order the troops to retire about 300 meters from the barbed wire and dig in.[19] The advance of Major von Hamerstein, met with strong rifle and monitor fire, achieved little. Colonel Drazhkov, meanwhile, repelled Romanian flanking attacks, but his advance was stalled by strong artillery fire at about 50 meters from the Romanian barbed wire. Overall, the attackers in this sector suffered around 300 casualties.[20] They did not achieve their objectives, and had to wait until the next day as darkness settled over the battlefield.

After a rainy night the 4th Preslav Division used 3 September to approach the barbed wire of the main defensive line in Sector II, driving away Romanian patrols, taking Daidâr (now Shumentsi), and repositioning its heavy artillery. In the process the division repelled several Romanian counterattacks, while sustaining light casualties. In Sector III the 1/1 Infantry Brigade managed to close in on the main defensive line without opposition.

The Romanian position was gradually deteriorating. General Teodorescu was forced to respond to requests from the commanders of sectors I and III for reinforcements by sending them his last reserves (which would prove futile, as the main Bulgarian attack was to be delivered in Sector II). Despite Teodorescu's pessimistic reports, the Romanian high command retained its hope that the fortress would hold until relieved by Romanian and Russian forces advancing from the east, or that the garrison would be able to break the encirclement and retreat to Silistra.[6] On 3 September the first attempts to assist Turtucaia were made by the Romanian soldiers on the right wing of the Bulgarian Third Army, but they were defeated by the Bulgarian 1st Cavalry Division at the villages of Cociumar and Karapelit, where a brigade of the Romanian 19th Division suffered the following casualties: 654 killed or wounded and at least 700 captured.[21]

At about 11 am on 3 September General Toshev, having exchanged thoughts with General Kiselov, issued Order No. 17 for the next day's attack on Turtucaia. It stated that the commander of the 4th division was to assume control over all forces operating against the fortress and determine the exact hour of the infantry attack, once the preliminary artillery barrage had inflicted sufficient damage. Major von Hammerstein and his group were to attack and take fort 2 in Sector I (West), the main attack was to be delivered by the 4th Division against forts 5 and 6 in Sector II (South), and finally, the 1/1 Brigade was to capture fort 8 in Sector III (East). To protect the right flank of these forces, General Toshev tasked the remaining two brigades of the 1st Sofia Infantry division with monitoring Romanian activity in Silistra.[22] When Kiselov received this order, he used his new position as overall operational commander to make several changes to the plan. Forts 5 and 6 were now to be attacked only by the Kmetov Brigade, while the Ikonomov Brigade was directed against fort 7. All the heavy artillery was placed under the commander of the 2nd Heavy Regiment, Colonel Angelov, who was to execute the planned artillery barrage from 9 am. The infantry was to approach to within 150 meters and wait for the barrage to end. Angelov, however, felt that intelligence on the Romanian positions was insufficient and that the Bulgarian batteries needed better positioning, so he asked that the attack be postponed for one day. In addition, communication with von Hammerstein's group was weak, and the two German minenwerfer companies that were crucial for the advance in that sector needed more time to position themselves. This convinced general Kiselov to delay the attack.

September 4 was spent in additional preparation for the attack. Active fighting continued only in Sector I, where von Kaufman's detachment had to finish the attack on height 131, which it had started the previous day, and secure the staging ground for the assault on fort 2. This objective was achieved early in the morning with relative ease, most of the Romanian defenders having retired to the main defensive line. That day field marshal Mackensen recalled von Kaufman to Byala, and the German - Bulgarian detachment was placed under the command of Major von Hammerstein.[23]

General Teodorescu continued sending pessimistic and even desperate reports to the Romanian high command and asking for reinforcements. This time he was not ignored: the 10th and 15th divisions, representing the army's strategic reserve, were ordered to move south towards Olteniţa - the first to guard the river shore and the latter to prepare to cross the Danube and assist the garrison in Turtucaia. These were seventeen battalions from the Romanian 34th, 74th, 75th, 80th regiments plus one battalion from the 84th Regiment and 2 battalions from the 2nd Border Regiment, supported by 6 artillery batteries.[13] These new, fresh troops allowed the Romanians to gain numerical superiority over the Bulgarians, but once again they were delayed on their way and would arrive gradually on the battlefield, reducing their impact on the overall course of the battle.[13] The first reinforcements crossed the Danube late in the afternoon and during the night on 4 September. When they stepped on the southern shore they were immediately parceled out to strengthen the different sectors, with no regard for the direction of the main Bulgarian attack or for the establishment of a sufficient reserve.

Fall of the fortress (5–6 September)

By 5 September the garrison had been able to strengthen some parts of the main defensive line with the help of the newly arriving reinforcements. In Sector I, forts 1 to 5 were guarded by nine and a half battalions chiefly from the Romanian 36th Infantry regiment, stiffened with battalions from the 40th, 75th and 80th infantry regiments, as well as four companies from 48th and 72nd militia battalions. Sector II was reinforced with 4 battalions of the 74th and 75th regiments to a total of 8 battalions, but only after the attack had started. Sector III was also reinforced as the assault developed by various infantry, militia and border units until it reached a strength of 14 battalions. The initial reserve of the fortress had been spent on reinforcing the lines, and only on 5 September was a small reserve of newly arrived reinforcements established. It consisted of one infantry battalion, one border battalion, and one infantry company.

Thus in the decisive Sector II the Bulgarians were able to secure a substantial numerical superiority during the initial phase of the assault:

| Forces in Sector 2 [24] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Men/Material | Quantity | Ratio | Density | ||||||||||||||||||

| Bulgarian | Romanian | Bulgarian | Romanian | Bulgarian | Romanian | ||||||||||||||||

| Battalions | 9 | 4 | 2.25 | 1 | 3 | 1.3 | |||||||||||||||

| Cannons | 80 | 57 | 1.4 | 1 | 8 | 5.7 | |||||||||||||||

| Machine Guns | 12 | 17 | 1 | 1.4 | 4 | 5.7 | |||||||||||||||

| Squadrons | 1 | - | - | - | 0.3 | - | |||||||||||||||

| Combatants | 18,000 | 6,300 | 2.7 | 1 | 6,000 | 2,100 | |||||||||||||||

At 5:30 am a Bulgarian observation balloon pulled by an automobile ascended to the sky to direct the planned barrage. Exactly an hour later Colonel Angelov gave the order for the preliminary artillery bombardment to begin. The cannons concentrated their fire on the forts and obstacles between them, and at 7:40 am the observation post at Daidâr reported that groups of Romanian soldiers were leaving forts 5 and 6, making their way through the communication trenches leading to the rear. The Romanian batteries tried to respond, but the effort was not well coordinated; their sporadic fire (indicating low stocks of ammunition) wasn't aimed at the heavy batteries of the attackers, and their fire ceased immediately after the Bulgarians had opened fire at them. The power of the Bulgarian barrage even deceived General Teodorescu into believing that it was executed by 30.5 cm cannons, when in fact there were none. By 8:00 am three out of four fortress batteries in Sector II had their fire suppressed or were destroyed, which forced Teodorescu to send the 1/5 Howitzer Section to the area. It took up position behind fort 8 without being noticed by the Bulgarians.

At about 8:00 am Colonel Angelov informed General Kiselov and Lieutenant Colonel Noykov that in his opinion the artillery had achieved sufficient results for the infantry to begin its advance. The general was not entirely convinced, but as the artillery barrage was supposed to continue while the infantry was approaching the line, he ordered the commanders of the 3/4, 1/4 and 1/1 infantry brigades to begin the attack, and all officers to make an example by personally leading their men in the assault. Later this order was also received by von Hammerstein and the commander of the 47 Infantry Regiment.

According to plan, Colonel Kmetov's brigade attacked forts 5 and 6, which were defended by the Romanian 79th Infantry Regiment. The 19th Shumen Regiment, divided in two groups and supported by the 48th Regiment, prepared to descend along a slope directly facing the Romanian fortifications to the bottom of the ravine in front of the Daidâr village. As soon as the infantry began advancing it was met with strong rifle and machine gun fire supported by the smaller caliber Romanian turret guns that had survived. Bulgarian field and heavy artillery, still concentrated on Romanian batteries behind the defensive line, provided little direct support. Assisted by covering fire from its machine guns, the brigade managed to reach the first obstacles in front of the main defensive line by 10:30 am, and the infantry rushed them and the barbed wire through passages made by the pioneers under heavy fire. Half an hour later the 1/19 battalion and part of the 3/48 battalion, which were part of the brigade's right group, captured fort 6 and the trenches to the east of it.[25] The left group was temporarily held up by Romanian fire, but by 12:30 it had driven the Romanians out of their trenches and achieved control of the main defensive line in that part of the sector. After the fall of forts 5 and 6 the Bulgarians pursued the retreating defenders until 16:00, advancing two kilometers to the north of the main defensive line. The Kmetov Brigade captured 250 soldiers, 4 heavy batteries, six 53 mm turret guns and many rifles. Its artillery had fired 2,606 shells. Both Romanian and Bulgarian infantry losses were heavy, with the 19th Shumen Regiment suffering 1,652 casualties.[26]

To the east of the 3/4 Brigade was the Ikonomov Brigade, tasked with the capture of fort 7. During the night, its 7th Preslav and 31st Varna Infantry Regiments had gotten within 600 meters of the line's artificial obstacles. They began their assault at about 8:00 am on 5 September, but, in spite of suppressing fire from their artillery, met strong Romanian resistance. At 9:30 the forward units were forced to halt and take cover some 200 meters from the obstacles. This was partly a result of the shifting of positions of the Bulgarian artillery, as the 1/15 artillery section had been ordered to move forward in direct support of the advancing infantry. The section took up new positions on a ridge east of Daidâr and immediately opened fire on the trenches around forts 6 and 7. At 10:30 the 31st Regiment rushed the obstacles and, under heavy fire, began scaling the slope leading to fort 7. The Bulgarians managed to enter the fort and its neighboring trenches, where they were engaged in a costly close quarter battle while exposed to fire from their own artillery. By 11:20 the Romanians had been completely expelled, but with its commander wounded and its units disorganized the 31st Regiment did not pursue, and was content with firing on the retreating defenders from the trenches.

The 7th Preslav Regiment meanwhile had been faced with even stronger Romanian fire, and was able to advance only at about 12:00, when its commander, Colonel Dobrev, personally led the assault against a fortification thought by the Bulgarians to be fort 8, but which was actually one of the so-called subcenters of defense that were situated in the gaps between the forts. Many of the defenders had retreated from the line, and those who remained were captured. Parts of the regiment continued to pursue beyond the main defensive line until 13:35, when Colonel Dobrev ordered them to halt. When it was realized that this was not fort 8 he ordered his infantry to cut the retreat routes of that fort, but the Romanians managed to prevent this with artillery fire.

By the afternoon of 5 September the forts of the main defensive line in Sector II had all fallen into the hands of the attackers.[13] The Romanian 79th Regiment which had defended the sector was practically destroyed. It was left with only 400 effectives,[6] having suffered 46 officers and 3,000 soldiers killed or wounded.[13] The newly arriving Romanian battalions were unable to prevent the Bulgarian breakthrough, and, with the remnants of the 79th Regiment, tried to prepare the secondary defensive line. In this they were helped by the thick forest behind the main defensive line, which made it hard for the Bulgarian units - intermixed, disorganized, and unprepared for their own success - to advance.

In Sector III the artillery bombardment began at 6:55, and by 8:15 had achieved considerable success in damaging the Romanian fortifications, forcing some of the defenders to flee to the rear and the Danube.[13][27] The 1st and 6th Bulgarian regiments advanced through a large corn field that made their movement almost undetectable and by 11:30 reached the plateau north of Antimova. Only now did the Romanians in forts 8 and 9 spot them and open fire, temporarily halting the Bulgarian advance. Colonel Nedialkov, who was with the supporting units, immediately ordered part of the artillery to move forward and directly support the infantry. Following this the 1st Sofia Regiment and the neighboring 4/6 battalion rushed the barbed wire and crossed it without difficulty. This and the breakthrough achieved by the 4th Preslav Division to the west caused the wavering Romanian soldiers to abandon their trenches and retreat to the rear, and by 13:30 the surrounding trenches of fort 8 had fallen. The fort itself was taken simultaneously by parts of the 1st and 7th regiments.[28] After these successes the brigade was directed to conquer the remaining parts of the Eastern Sector, including forts 9, 10, 11 and 12. Meeting little resistance, as the arriving Romanian reinforcements were often caught up by retreating units and compelled to join them, the Bulgarians accomplished this task and by 21:30 reached the shore of the Danube, completing the isolation of the fortress.[6]

The attack in Sector I was delayed considerably as Major Hammerstein gave orders to the three groups of his detachment for the attack on fort 2;[29] he also demanded a prolonged artillery bombardment to better secure the advance of the infantry. So it was only at 14:30, when the guns concentrated their fire on the fort itself, that the major gave the order for the first and second groups to attack. Despite the artillery fire they faced, the Bulgarians and Germans advanced with relative ease as the Romanians, despite their large number, began retreating and even fleeing in panic to Turtucaia. Around 13:00 general Teodorescu ordered the commander of the sector to abandon forts 2, 3, 4 and 5.[13] By the end of the day only fort 1 was still in Romanian hands, as it had powerful artillery cover from the Danube monitors and batteries on the left bank of the river.

By the evening of 5 September the entire main defensive line (save two forts) had been taken, along with all of the Romanian fixed artillery and part of the mobile artillery. The Romanian units were so disorganized that a planned counterattack with the new reinforcements from the 15th Division had to be postponed for the next day.[13] The Bulgarian units, especially those of the 4th Infantry Division, had also suffered heavy casualties and needed the night for reorganization and better positioning of their artillery.

General Kiselov was visited by both General Toshev and Colonel Tappen, Mackensen's chief of staff. Both men were pleased with the day's events, and, despite the heavy casualties, urged him to carry on with the attack.[6][30]

Resumption of the attack

During the night of 5 September the Romanians established themselves as best they could on their much weaker secondary defensive position. General Teodorescu ordered a redeployment of forces so that 9 battalions were to defend Sector I, 12 battalions Sector II, 2 battalions Sector III and 5 battalions Sector IV, while an additional 7 battalions remained in reserve. This order, however, reached the troops only in the morning and the units were not able to execute it.

At around 4:30 am on 6 September the Bulgarian artillery again opened fire in sectors I and III. Men of the Bulgarian 4th division began crossing the large forest that separated the two main and secondary defensive lines. Aided by the powerful artillery preparation, the Bulgarian 7th and 31st infantry regiments advanced rapidly. By 12:30 they had passed through the trenches that had been abandoned by their defenders earlier in the day. At around 15:00 the two regiments of the 1/4 Brigade gathered on the hill overlooking Turtucaia itself. Meanwhile, the Kmetov Brigade also advanced, though not as quickly and with greater disorganization. Parts of it reached the northern end of the forest at 13:00 and immediately attacked the Romanian trenches, but it was only at 15:30 that the trenches were occupied, most of the defenders having already pulled out due to the success of the 1/4 Brigade and the artillery bombardment. By 17:30 the brigade reached the hill overlooking the town.

The 1/1 Infantry Brigade was ordered to coordinate its actions with the 4th Division and advance against the right flank of the defensive line. At about 6:50, while still waiting to go forward, the units came under attack from several Romanian battalions which threatened to envelop their flank, but who were stopped by Bulgarian reinforcements. After this both the 1st and 6th regiments advanced, and by 11:30 had come within 800 meters of the line. The Romanian defenders, believing that a Russian column was advancing from the east to help the encircled fortress, put up stout resistance;[6] however, once they realized the "relief column" was in fact Bulgarian, they started retreating in panic.[13] So the 1/1 Brigade was allowed to reach the vicinity of the town at 17:00.

In Sector I, Major Hammerstein's detachment entered the forest at 10:00, where it met very weak Romanian vanguards that were swiftly pushed back. During the afternoon it took fort 1 in the face of more determined Romanian resistance, then continued advancing until it was lined up next to the 4th Division.

The only way the garrison could now be saved was with help from outside forces, and as early as 5 September General Aslan ordered the commander of the 9th Division, General Ioan Basarabescu, to advance decisively from Silistra and relieve the besieged town.[13] The commander executed this order by leaving 4 battalions in Silistra and sending the remaining 5 battalions, 4 batteries and 2 squadrons to break the siege. On 6 September these forces were met and defeated by the Bulgarian 3/1 Infantry Brigade, which had been ordered to protect the flank of the army, at the village of Sarsânlar (now Zafirovo), some 18 kilometers to the east of Turtucaia.[6][13] This sealed the fate of the garrison.

With the situation deteriorating rapidly, General Teodorescu ordered his men to retreat and if possible try to break the encirclement in the direction of Silistra. At 13:40 he himself boarded a boat to cross the Danube, leaving behind thousands of panicked soldiers, some of whom tried to follow his example but ended drowning in the river or being hit by artillery fire.[6] Romanian attempts to break out and escape towards Silistra also proved largely unsuccessful in the face of the Bulgarian artillery. As the Bulgarians entered the town the defenders began surrendering in large groups. At 15:30 colonel Mărășescu, who was now in charge of the garrison, and his senior officers wrote a note to general Kiselov in German and dispatched it to three of the sectors, offering the unconditional surrender of the fortress together with all its men and material.[31] At 16:30 one of the truce-bearers reached the Bulgarian 1/31 battalion and was immediately dispatched to Colonel Ikonomov, who at 17:30, via telephone, informed General Kiselov of the note and its contents.[31] Kiselov accepted the surrender on the condition that all military personnel be gathered on the plateau south of the town's barracks before 18:30.[31]

Aftermath

Casualties

The Romanians committed around 39,000 men for the defense of the Turtucaia fortress, and over 34,000 of them became casualties. Only between 3,500 and 4,000 managed to cross the Danube or make their way to Silistra.[13] These were the troops of the 9th Infantry Division, safely evacuated by the four river monitors.[9] While the number of killed and wounded rose to between six and seven thousand men, the vast majority of the garrison - some 480 officers and 28,000 soldiers - surrendered or were captured by the Bulgarians.[1][33] The attackers also captured all the military material of the fortress, including 62 machine guns and around 150 cannons, among them two Bulgarian batteries captured by Romania during the Second Balkan War. The heaviest fighting was in Sector II where the 79th Regiment, which in general was the unit that resisted the attacks the most, suffered 76% losses - out of 4,659 men some 3,576 were killed or wounded.[34]

Bulgarian casualties were heavy. From 2 to 6 September they totaled 1,517 killed, 7,407 wounded and 247 missing.[1] Of these, only 93 were killed and 479 wounded between 2 and 4 September.[1] Around 82% of the total losses - 1,249 killed and 6,069 wounded - occurred on 5 September during the attack of the main defensive line.[35] The heaviest fighting was in Sector II where, in one example, the 7th Preslav Infantry Regiment had 50% of its officers and 39.7% of its soldiers killed or wounded. Characteristically, almost all of casualties were suffered by the infantry, the heavy artillery having only 2 killed and 7 wounded.[1] German casualties were 5 killed and 29 wounded.

Impact on the campaign

The rapid fall of Turtucaia and the loss of two infantry divisions was a surprise with crucial consequences for the entire Romanian Campaign. Most importantly, it unnerved the Romanian High Command and severely affected the morale of the army and the people. The scale of the defeat forced Romania to detach several divisions from its armies in Transylvania, greatly reducing the impetus of the advance there. On 7 September that advance was restricted by the Romanian high command, and on 15 September it was halted altogether, even before the armies had linked up on a defensible front.[6] Major changes were made in the command structure of the forces operating against the Bulgarian Third Army. General Aslan and his chief of staff were sacked. Command of the Romanian Third Army was taken over by General Averescu, and the Russo-Romanian forces in Dobruja were reorganized as the Dobruja Army under General Zayonchkovski.

The speed with which the victory was achieved was so unexpected by the Central Powers that even Field Marshal Mackensen, who was usually present on the site of important battles, hadn't planned to arrive on the battlefield until several days after the actual capitulation of the fortress. It boosted the morale of the Bulgarians and their allies as far away as the Macedonian front, as well as in political circles in Berlin and Vienna. Kaiser Wilhelm, who had been particularly depressed by Romania's entry into the war, celebrated with a champagne party for the Bulgarian representative at the headquarters of the German High Command.[6] The suspension of the Romanian offensive in Transylvania, which had threatened to overrun the province, gave General Falkenhayn enough time to concentrate his force and go on the offensive by the end of September.

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 Министерство на войната (1939), pp. 677

- ↑ According to Romanian sources Тутраканска епопея Archived June 24, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 Dragoş Băldescu, "Bătălia de la Turtucaia (1916)", Colecţionarul Român, 24.12.2006

- ↑ Glenn E. Torrey, "The Battle of Turtucaia (Tutrakan) (2–6 September 1916): Romania's Grief, Bulgaria's Glory"

- ↑ Constantin Kiriţescu, "Istoria războiului pentru întregirea României: 1916–1919", vol. I, pag. 398

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Glenn E. Torrey (2003)

- 1 2 3 4 5 Petar Boychev (2009) page 4-5

- 1 2 3 Министерство на войната (1939).

- 1 2 Spencer Tucker, Priscilla Mary Roberts, World War I: Encyclopedia, Volume 1, p. 999

- ↑ Министерство на войната (1939),p.263-4

- ↑ Тошев (2007), page 18

- ↑ Petar Boychev (2009) page 7

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Constantin Kirițescu, "Istoria războiului pentru întregirea României: 1916–1919", vol. I,

- 1 2 3 Министерство на войната (1939), pp. 326-331

- ↑ Министерство на войната (1939), pp. 363

- ↑ Министерство на войната (1939), pp. 331-332

- ↑ Министерство на войната (1939), pp. 394

- ↑ Министерство на войната (1939), pp. 399

- ↑ Министерство на войната (1939), pp. 402

- ↑ Министерство на войната (1939), pp. 678

- ↑ Министерство на войната (1939), pp. 451

- ↑ Министерство на войната (1939), pp. 469

- ↑ Министерство на войната (1939), pp. 478

- ↑ Petar Boychev (2009) page 8

- ↑ Министерство на войната (1939), pp. 536

- ↑ Министерство на войната (1939), pp. 540

- ↑ Министерство на войната (1939), pp. 552

- ↑ Министерство на войната (1939), pp. 556

- ↑ Министерство на войната (1939), pp. 561

- ↑ Министерство на войната (1939), pp. 596

- 1 2 3 Министерство на войната (1939), pp. 668

- ↑ "Dead Bulgarian Soldiers along Danube after Battle of Turtucaia". Museum Syndicate. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- ↑ Otu. The Battle of Turtucaia at Radio Romania Archived August 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Министерство на войната (1939), pp. 680

- ↑ Министерство на войната (1939), pp. 676

References

- Министерство на войната, Щаб на войската (1939). Българската армия въ Световната война 1915–1918. Томъ 8: Войната срещу Ромъния презъ 1916 година 1915–1918, Vol. VIII. Държавна печатница, София.

- Glenn E. Torrey, "The Battle of Turtucaia (Tutrakan) (2–6 September 1916): Romania's Grief, Bulgaria's Glory".East European Quarterly, Vol. 37, 2003

- Boychev, Petar (2009). "The Tutrakan Epic" (PDF) (in Bulgarian). Военноисторически сборник/MILITARY HISTORICAL COLLECTION. pp. 3–14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-01-13. Retrieved 2010-09-13.

- Тошев, Стефан (2007). Действията на III армия в Добруджа през 1916 год. Захарий Стоянов. ISBN 978-954-739-976-1.

- Stefanov, Stefan (5 September 2006). "'Impregnable' fortress falls after 33 hours" (in Bulgarian). Dneven Trud. p. 18.

- Constantin Kiriţescu, "Istoria războiului pentru întregirea României: 1916–1919", 1922

- Тутраканската епопея

- The Battle of Turtucaia at Radio Romania