| Battle of Zusmarshausen | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Thirty Years' War | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

22,000

|

15,370–18,000[2]

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 500[3] |

1,897[4]–2,200[2] 6 Guns | ||||||

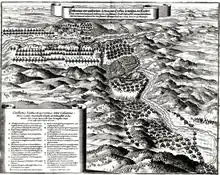

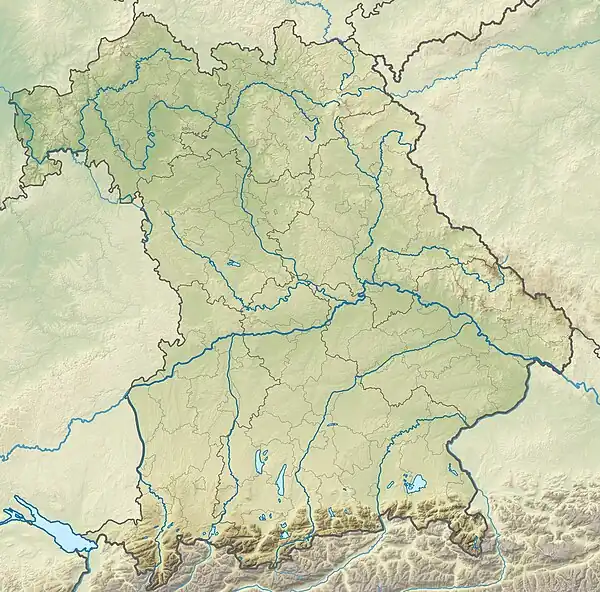

The Battle of Zusmarshausen was fought on 17 May 1648 between Bavarian-Imperial forces under von Holzappel and an allied Franco-Swedish army under the command of Carl Gustaf Wrangel and Turenne in the modern Augsburg district of Bavaria, Germany. The allied force emerged victorious, and the Imperial army was only rescued from annihilation by the stubborn rearguard fighting of Raimondo Montecuccoli and his cavalry.[5]

Zusmarshausen was the last major battle of the war to be fought on German soil during the Thirty Years' War, and was also the largest battle (in terms of numbers of men involved; casualties were relatively light) to take place in the final three years of the war.

Background

By the late 1640s all the belligerents in the Thirty Years' War were exhausted by three decades of brutal fighting. Delegates had already convened in the Westphalian cities of Münster and Osnabrück to negotiate a peace treaty in 1646, but while the peace talks were in progress the opposing powers continued to jockey for position in order to improve their respective positions in the negotiations. The Swedes in particular were keen to win a final decisive victory against the Habsburg monarchy in order to secure territorial concessions within the Holy Roman Empire, and also to make the most of the war while it lasted by invading and plundering the rich Habsburg province of Bohemia, which was one of the few parts of the Empire to have been left largely untouched by the fighting so far.

Prelude

There were four armies involved in the Zusmarshausen campaign. On one side was the main Imperial field army of 10,000 men commanded by Peter Melander Graf von Holzappel, and a Bavarian force of 14,000 under Jost Maximilian von Bronckhorst-Gronsfeld. Opposing them was the 20,000-strong Swedish army under Carl Gustaf Wrangel, and a French army of 6,000 men commanded by Marshal Turenne, France's ablest general of the period.[1]

Wrangel began the 1648 campaign by leaving the Swedish base at Bremen and marching south up the Weser, while simultaneously Turenne advanced from Alsace and marched north along the Rhine to meet him, the plan being to join forces on the River Main. Melander attempted to prevent his two enemies from combining, but the obstructionism of his ostensible ally Archbishop-Elector Ferdinand of Cologne hindered his movements, prohibiting the Westphalian army under General Lamboy to leave his territory, and Melander was eventually compelled to retreat to avoid being caught between the French and Swedish armies. Wrangel and Turenne were therefore able to join forces and push southeast into Franconia, forcing Melander to retreat into Bavaria, and specifically to Ulm, where he was subsequently joined by Gronsfeld's Bavarian troops.[1]

In May the Franco-Swedish army advanced southward into Württemberg and then swung east to confront Melander and Gronsfeld in Bavaria. By this point disease and desertion had whittled the Imperial-Bavarians down to 16,000 men, and they therefore found themselves outnumbered by a ratio of around 3:2. Moreover, Melander was under orders from Emperor Ferdinand III not to risk his army, as a decisive defeat could have drastic consequences for the peace negotiations in Westphalia. He therefore decided to retreat again rather than confront Wrangel and Turenne, and ordered his troops to pull out of Ulm and march eastward toward Augsburg. To cover the retreat he detached a force of 2000 Croatian cavalry under Raimondo Montecuccoli to perform a rearguard action at a bridge over the Zusam river, in the village of Zusmarshausen.[1]

Battle

The battle began at 7 AM on 17 May, when Montecuccoli's troops in Zusmarshausen came under attack from the Swedish vanguard. Montecuccoli held off the Swedish attacks for an hour before ordering his men to pull back eastward to the village of Herpfenried, where they mounted another stand. This time, however, a group of French cavalry managed to work their way round the southern side of Montecuccoli's position, threatening to cut him off from the rest of the Imperial-Bavarian army. Melander himself dashed back to rescue the rearguard, and in the resulting melee the general was shot in the chest and killed.[4]

Montecuccoli managed to extricate his surviving men from Herpfenried around midday, and at 2 PM he rejoined Gronsfeld and the rest of the army, which had assumed a defensive position on the east bank of the Schmutter. Later that afternoon the French vanguard appeared and made a couple of probing attacks across the river, but they lacked the strength to mount a serious assault (most of the Franco-Swedish army was still strung out along the road from Ulm) and night fell before these forces could become available.[4]

Under cover of darkness Gronsfeld abandoned the makeshift earthworks on the Schmutter and completed the retreat to Augsburg. The losses of the Imperial-Bavarian army were 1,582 dead or wounded, 315 prisoners, 6 field guns, parts of the baggage and the fallen commander von Holzappel but the bulk of the force escaped.[4]

Aftermath

Gronsfeld intended to hold a defensive position at the Lech river against the enemy. Yet after receiving a (highly exaggerated) report that the Swedes were fording the river on 26 May, he deemed his forces too weak to push them back. An Imperial-Bavarian war council decided to retreat to Ingolstadt, only Gronsfeld's second-in-command Hunolstein objected the decision, anticipating the elector's reaction.[6] Maximilian I, Elector of Bavaria was indeed furious that Gronsfeld had abandoned so much of Bavaria without a fight, and arrested him on 3 June. His interim successor became Feldzeugmeister Hunolstein while the imperials assigned Ottavio Piccolomini as supreme commander. Their opponents' retreat allowed Wrangel and Turenne to advance across southern Bavaria and to plunder the area between Lech and Isar where the Swedes took Freising and Landshut.[7]

Despite the army being shrunk by desertions to at one point only 10,000 men, Hunolstein prevented Wrangel from crossing the fortified and heavily swollen river Inn in southern Bavaria and reorganized the defense together with Piccolomini. The latter improved his men's morale by bringing 3,100 reinforcements and using his own money to pay the arrears in their wages. Wrangel and Turenne, unable to advance further, started to retire their troops. Piccolomini went on the offensive in July, harassing the enemy without being drawn into a pitched battle. In August, Johann von Werth arrived from Bohemia with additional 6,000 cavalry whereas the Bavarians put Adrian von Enkevort in command instead of Hunolstein.[8] Back to 24,000 strength and about equally numbered to Swedes and French, Piccolomini slowly manoeuvred them out of Bavaria, even achieving a minor victory at Dachau on 6 October and clearing Bavaria from enemy troops between Inn and Lech.[9]

However, the Swedes took advantage of the weakened defences in Bohemia; a second Swedish army under Königsmarck took the castle and the Malá Strana district of Prague by surprise on 25 July. Their following siege of the Old and the New Town at the other side of the Vltava river continued even after the final conclusion of the negotiations in Münster and Osnabrück with the Peace of Westphalia on 24 October. The Swedes failed to capture the larger Old Town of Prag until news of the peace treaty arrived on 5 November, followed by an imperial relief force sent by Piccolomini.[10]

Montecuccoli later became one of the Habsburg Monarchy's most accomplished generals, and he and Turenne met again as opposing commanders in the Franco-Dutch War, first in the 1673 campaign and then again in 1675.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wilson, Peter (2010). Europe's Tragedy: A New History of the Thirty Years War. Penguin Books. pp. 738–740.

- 1 2 Grant 2017, p. 344.

- ↑ Höfer 1998, p. 195.

- 1 2 3 4 Wilson, Peter (2010). Europe's Tragedy: A New History of the Thirty Years War. Penguin Books. pp. 740–741.

- ↑ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 18 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 764–765, midway down.

...and at the battle of Zusmarshausen in 1648 his stubborn rearguard fighting rescued the imperialists from annihilation

- ↑ Höfer 1998, pp. 200–203.

- ↑ Wilson, Peter (2010). Europe's Tragedy: A New History of the Thirty Years War. Penguin Books. pp. 741–743.

- ↑ Wilson, Peter (2010). Europe's Tragedy: A New History of the Thirty Years War. Penguin Books. pp. 743–744.

- ↑ Höfer 1998, pp. 221–226.

- ↑ Wilson, Peter (2010). Europe's Tragedy: A New History of the Thirty Years War. Penguin Books. pp. 744–747.