| Belo Monte Dam | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Main dam | |

Location of the Belo Monte Dam in Brazil | |

| Official name | Complexo Hidrelétrico Belo Monte |

| Location | Pará, Brazil |

| Coordinates | 3°7′40″S 51°46′33″W / 3.12778°S 51.77583°W |

| Status | Operational |

| Construction began | 2011 |

| Opening date | 2016 |

| Construction cost | US$18.5 billion (estimated) |

| Owner(s) | Norte Energia, S.A. |

| Operator(s) | Eletronorte |

| Dam and spillways | |

| Type of dam | Composite |

| Impounds | Xingu River |

| Height | Belo Monte: 90 m (295 ft) Pimental: 36 m (118 ft) Bela Vista: 33 m (108 ft)[1] |

| Length | Belo Monte: 3,545 m (11,631 ft) Pimental: 6,248 m (20,499 ft) Bela Vista: 351 m (1,152 ft)[1] |

| Dam volume | Belo Monte and embankments: 25,356,000 m3 (895,438,689 cu ft) Pimental: 4,768,000 m3 (168,380,331 cu ft) Bela Vista: 239,500 m3 (8,457,863 cu ft)[1] |

| Spillways | 2 (Pimental and Bela Vista Dams) |

| Spillway type | Pimental: 17 gates Bela Vista: 4 gates |

| Spillway capacity | Pimental: 47,400 m3/s (1,673,915 cu ft/s) Bela Vista: 14,600 m3/s (515,594 cu ft/s)[1] |

| Reservoir | |

| Creates | Dos Canais Reservoir (Belo Monte, Bela Vista Dam) Calha Do Xingu Reservoir (Pimental Dam) |

| Total capacity | Dos Canais: 1,889,000,000 m3 (1,531,437 acre⋅ft) Calha Do Xingu: 2,069,000,000 m3 (1,677,366 acre⋅ft)[1] |

| Catchment area | 447.719 km2 (173 sq mi) |

| Surface area | Dos Canais: 108 km2 (42 sq mi) Calha Do Xingu: 333 km2 (129 sq mi)[1] |

| Maximum water depth | 6.2–23.4 m (20.3–76.8 ft) |

| Power Station | |

| Operator(s) | Eletronorte |

| Commission date | November 2019 |

| Hydraulic head | Belo Monte: 89.3 m (293 ft) Pimental: 13.1 m (43 ft)[1] |

| Turbines | Belo Monte: 18 x 611.11 MW Francis turbines Pimental: 6 x 38.85 MW Kaplan bulb turbines |

| Installed capacity | 11,233 MW[2] |

| Annual generation | 39.5 TWh[3] |

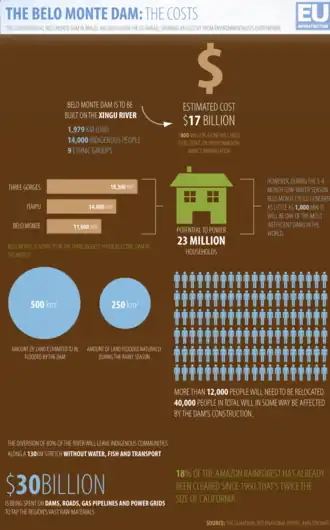

The Belo Monte Dam (formerly known as Kararaô) is a hydroelectric dam complex on the northern part of the Xingu River in the state of Pará, Brazil. After its completion, with the installation of its 18th turbine, in November 2019, the installed capacity of the dam complex is 11,233 megawatts (MW), which makes it the second largest hydroelectric dam complex in Brazil and the fifth largest in the world by installed capacity, behind the Three Gorges Dam, Baihetan Dam and the Xiluodu Dam in China and the Brazilian-Paraguayan Itaipu Dam. Considering the oscillations of flow river, guaranteed minimum capacity generation from the Belo Monte Dam would measure 4,571 MW, 39% of its maximum capacity.[4]

Brazil's rapid economic growth over the last decade has provoked a huge demand for new and stable sources of energy, especially to supply its growing industries. In Brazil, hydroelectric power plants produce over 66% of the electrical energy.[5] The Government has decided to construct new hydroelectric dams to guarantee national energy security. However, there was opposition both within Brazil and among the international community to the project's potential construction regarding its economic viability, the generation efficiency of the dams and in particular its impacts on the region's people and environment. In addition, critics worry that construction of the Belo Monte Dam could make the construction of other dams upstream- which could have greater impacts- more viable.

Plans for the dam began in 1975 but were soon shelved due to controversy; they were later revitalized in the late 1990s. In the 2000s, the dam was redesigned, but faced renewed controversy and controversial impact assessments were carried out. On 26 August 2010, a contract was signed with Norte Energia to construct the dam once the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA) had issued an installation license. A partial installation license was granted on 26 January 2011 and a full license to construct the dam was issued on 1 June 2011. The licensing process and the dam's construction have been mired in federal court battles; the current ruling is that construction is allowed, because the license is based on five different environmental technical reports[6] and in accordance with the RIMA (Environmental Impact Report, EIA-RIMA) study for Belo Monte.[7]

The first turbines went online on 5 May 2016.[8] As of October 2019 all turbines at Pimental and 17 turbines in main power powerhouse are online with total installed capacity of 10,388.87 MW at Belo Monte site, totaling 10,621.97 with the Pimental site.[9] The power station was completed in November 2019.[10]

History

Plans for what would eventually be called the Belo Monte Dam Complex began in 1975 during Brazil's military dictatorship, when Eletronorte contracted the Consórcio Nacional de Engenheiros Consultores (CNEC) to realize a hydrographic study to locate potential sites for a hydroelectric project on the Xingu River. CNEC completed its study in 1979 and identified the possibility of constructing five dams on the Xingu River and one dam on the Iriri River.[11]

Original plans for the project based on the 1979 study included two dams close to Belo Monte. These were: Kararaô (called Belo Monte after 1989), Babaquara (called Altamira after 1998) which was the next upstream.[11] Four other dams were planned upstream as well and they include the Ipixuna, Kakraimoro, Iriri and Jarina. The project was part of Eletrobras' "2010 Plan" which included 297 dams that were to be constructed in Brazil by 2010. The plan was leaked early and officially released in December 1987 to an antagonistic public. The plan had Belo Monte to be constructed by 2000 and Altamira by 2005. Such a speedy timetable was due to the belief that Brazil's relatively new environmental regulations could not stop large projects.[12] The government offered little transparency to the people who would be affected regarding its plans for the hydroelectric project, provoking indigenous tribes of the region to organize what they called the I Encontro das Nações Indígenas do Xingu (First Encounter of the Indigenous Nations of the Xingu) or the "Altamira Gathering", in 1989. The encounter, symbolized by the indigenous woman leader Tuíra holding her machete against the face of then-engineer José Antonio Muniz Lopes sparked enormous repercussions both in Brazil and internationally over the plans for the six dams. As a result, the five dams above Belo Monte were removed from planning and Kararaô was renamed to Belo Monte at the request of the people of that tribe. Eletronorte also stated they would "resurvey the fall", meaning resurvey the dams on the river.[12][13]

Redesign

Between 1989 and 2002, the Belo Monte project was redesigned. The reservoir's surface area was reduced from 1,225 km2 (473 sq mi) to 440 km2 (170 sq mi) by moving the dam further upstream. The main rationale for this was to reduce flooding of the Bacajá Indigenous Area. In 1998, the Babaquara Dam was again placed into planning but under a new name, the Altamira Dam. This surprised local leaders as they felt plans for the dams above Belo Monte were cancelled. Some officials in Brazil were determined to build a dam on a river with an average flow of 7,800 m3/s (275,454 cu ft/s) and at a site that offers a 87.5 m (287 ft) drop. One engineer said of the dam: "God only makes a place like Belo Monte once in a while. This place was made for a dam."[12] President of Eletronorte, José Muniz Lopes, in an interview with the newspaper O Liberal (Belo Monte entusiasma an Eletronorte por Sônia Zaghetto, 15 July 2001), affirmed:

"Within the electric sector's planning for the period 2010/2020, we’re looking at three dams – Marabá (Tocantins river), Altamira (previously called Babaquara, Xingu River) and Itaituba (São Luís do Tapajós). Some journalists say that we are not talking about these dams because we’re trying to hide them. It’s just that their time has not yet come. We’re now asking for authorization to intensify our studies for these dams. Brazil would be greatly benefited if we could follow Belo Monte with Marabá, then Altamira and Itaituba."[13]

Second study

In 2002, Eletronorte presented a new environmental impact assessment for the Belo Monte Dam Complex, which presented three alternatives. Alternative A included the six original dams planned in 1975. Alternative B included a reduction to four dams, dropping Jarina and Iriri. Alternative C included a reduction to Belo Monte only. The new environmental impact assessment contained reductions in reservoir size and the introduction of a run-of-the-river model, in contrast to the large reservoirs characteristic of the 1975 plans.[14]

Also in 2002, Workers' Party leader Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva earned a victory in his campaign for president, having originally run unsuccessful campaigns in 1989, 1994 and 1998. Lula soon brokered political deals with the center and right-wing sectors in 2003, especially with ex-president José Sarney of the state of Maranhão of the PMDB, which would set the precedent that eventually characterized the two Lula administrations: cooperation between the market and the state, a combination of a free market economy with larger social spending and welfare. This economic model provided the rationale and financial support for new efforts to construct Belo Monte. In 2007, at the beginning of Lula's second term in office, a new national investment program was introduced: the Programa de Aceleração do Crescimento (Program to Accelerate Growth). The Belo Monte Dam Complex figured as an anchor project of the new investment plan.

In 2008, another new environmental impact assessment was written, this time by Eletrobras with the participation of Odebrecht, Camargo Corrêa, and Andrade Gutierrez, which formally accepted Alternative C or the construction only of the Belo Monte dam itself. The assessment also presented further design changes; in order to avoid inundating indigenous territory, which is not permitted by the Brazilian Constitution, the new design included two canals to divert the water away from indigenous territories and into a reservoir called the Reservatorio dos Canais (Canals Reservoir). An additional reservoir would be created called the Reservatorio da Calha do Xingu (Xingu Riverbed Reservoir), and electricity would be generated from the two reservoirs using three dams: a complementary powerhouse called Pimental (233 MW), a complementary spillway called Bela Vista, and the main powerhouse called Belo Monte (11,000 MW). The Reservatorio dos Canais would be retained by over a dozen large dikes, and water from the reservoirs would be channeled towards the main powerhouse.[15]

However, transparency of the government's plans once again became an issue, sparking indigenous tribes of the region to organize another large meeting, called the Segundo Encontro dos Povos do Xingu (the Second Encounter of the Peoples of the Xingu) in the city of Altamira, Pará on 20 May 2008.[16]

First license granted

In February 2010, Brazilian environmental agency IBAMA granted a provisional environmental license, one of three licenses required by Brazilian legislation for development projects. The provisional license approved the 2008 environmental impact assessment and permitted the project auction to take place in April 2010.[17][18]

In April 2010, Odebrecht, Camargo Corrêa, and CPFL Energia dropped out of the project tender, arguing that the artificially low price of the auction (R$83/US$47) set by the government was not viable for economic returns on investment.[19] On 20 April 2010, the Norte Energia consortium won the project auction by bidding at R$77.97/MWh, almost 6% below the price ceiling of R$83/MWh.[20] After the auction, local leaders around the project site warned of imminent violence. Kayapó leader Raoni Metuktire stated: "There will be a war so the white man cannot interfere in our lands again."[21] Canadian film director James Cameron also visited the site prior to the auction and stated he would produce an anti-Belo Monte Dam film called Message From Pandora which was later released in November.[22][23]

In April 2010 the Brazilian Federal Attorney General's Office suspended the project tender and annulled the provisional environmental license on claims of unconstitutionality.[24] Specifically, Article 176 of the Federal Constitution states that federal law must determine the conditions of mineral and hydroelectric extraction when these activities take place in indigenous peoples' territories, as is the case for the "Big Bend" (Volta Grande) region. As a result, the electric utility ANEEL canceled the project auction. The same day, the appellate court for Region 1 disenfranchised the Attorney General's suspension, reinstating the project auction at ANEEL.[25]

On 26 August 2010, President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva signed the contract with the Norte Energia at a ceremony in Brasília. Construction was not permitted to begin on the Belo Monte Dam Complex until IBAMA granted the second of the federally required environmental licenses, called the Installation License. The Installation License was only to be granted once Norte Energia shows indisputable proof that it has met 40 socio-environmental mitigation conditions upon which the first provisional environmental license was conditioned.[26] According to an October 2010 IBAMA report, at least 23 conditions had not been met.[22] Reports indicate that on 14 January 2011, a report from staff members of FUNAI, Fundação Nacional do Índio, (National Indian Foundation) had sent a report to IBAMA expressing concerns about the location of the project, its impact on reservation land, and the lack of attention to needs of the indigenous people, especially the Paquiçamba and recommending that FUNAI oppose any license to operate. Despite this report, FUNAI senior management sent IBAMA a letter on 21 January 2011 stating that it did not oppose the issuance of a limited construction license.[27]

On 26 January 2011, a partial installation license was granted by IBAMA, authorizing Norte Energia to begin initial construction activities only including forest clearing, the construction of easement areas, and improvement of existing roads for the transport of equipment and machinery.[28] In February 2011, Norte Energía signed contracts with multiple suppliers for the design, production, installation and commissioning of generation and associated equipment.[29] On 1 June 2011, IBAMA granted the full license to construct the dam after studies were carried out and the consortium agreed to pay $1.9 billion in costs to address social and environmental problems.[30] The only remaining license is one to operate the dam's power plant.[31]

Federal Court cases

On 25 February 2011, the Federal Public Prosecutor filed its 11th lawsuit against Belo Monte Dam, suspending IBAMA's partial installation license, on the grounds that the Brazilian Constitution does not allow for the granting of partial project licenses. The Federal Public Prosecutor also argued that the 40 social and environmental conditions tied to IBAMA's provisional license of February 2010 had yet to be fulfilled, a prerequisite to the granting of a full installation license.[32] On 25 February 2011, Brazilian federal judge Ronaldo Destêrro blocked the project citing environmental concerns.[32][33][34][35][36] It was Brazil's biggest public hearing ever.[33] The ruling was described by The Guardian as "a serious setback".[33] President of a federal regional court Olindo Menezes overturned the decision on 3 March 2011 saying there was no need for all conditions to be met in order for preliminary work to begin.[37][38] Construction site preparation began with a week after the decision.[39] On 28 September though, due to concerns for local fishers, a federal judge prohibited Norte Energia from "building a port, using explosives, installing dikes, building canals and any other infrastructure work that would interfere with the natural flow of the Xingu river, thereby affecting local fish stocks".[40][41] On 9 November, construction was allowed to recommence after federal judge Maria do Carmo Cardoso ruled that indigenous people did not have to be consulted by law before work approval. The ruling is expected to be appealed in the Supreme Federal Court.[42][43]

On 25 April 2012, a regional judge ruled an upcoming employee strike to be illegal. Workers were seeking improved payments and additional time-off. However, according to the court the contractor company did not violate its terms and as such, its employees will be fined for R$200,000 (US$106,000) per day if they do not attend.[44]

On 14 August 2012, work on the dam was halted by order of the Brazilian Federal Court, when federal judge Souza Prudente, halted construction on the controversial Belo Monte dam in the Amazon, saying that the indigenous peoples had not been consulted.[45] The Supreme Federal Court overturned the decision on 28 August and ordered construction to recommence.[46]

A federal court overturned a lower court ruling that had suspended the dam's operating license in January 2016. The lower court suspension was due to allegations of human rights violations.[47]

Design

Belo Monte reservoir inside, dam at top

The Belo Monte Dam (AHE Belo Monte) is a complex of three dams, numerous dykes and a series of canals in order to supply two different power stations with water. The Pimental Dam (3°27′33″S 51°57′31″W / 3.45917°S 51.95861°W) on the Xingu would be 36 metres (118 ft) tall; 6,248 metres (20,499 ft) long and have a structural volume of 4,768,000 cubic metres (168,400,000 cu ft). It would create the Calha Do Xingu Reservoir which would have a normal capacity of 2,069,000,000 cubic metres (1,677,000 acre⋅ft) and surface area of 333 square kilometres (129 sq mi). The dam would support a power station and its spillway would serve as the complex's principal spillway with 17 floodgates and a 47,400 cubic metres per second (1,673,915 cu ft/s) maximum discharge.[1] The dam's reservoir would also divert water into two 12 km (7 mi) long canals. These canals would supply water to the Dos Canais Reservoir, which is created within the "Big Bend" by the main dam, Belo Monte (3°06′44″S 51°48′56″W / 3.11222°S 51.81556°W), a series of 28 dykes around the reservoir's perimeter and the Bela Vista Dam (3°19′46″S 51°47′27″W / 3.32944°S 51.79083°W) which lies on the Dos Canais Reservoir's eastern perimeter. The Belo Monte Dam would support the main power station in the complex.[48][49] The power station was to have twenty vertical Francis turbines listed at 550 MW (max 560 MW). Supplying each turbine with water is a 113-metre-long (371 ft), 11.2 metres (37 ft) diameter penstock, affording an average of 89.3 metres (293 ft) of hydraulic head. The Pimental Dam's power station was to have seven Kaplan bulb turbines, each rated at 25.9 MW and with 13.1 metres (43 ft) of hydraulic head.[1] Later the unit count was decreased by using more powerful units (see next section).

The Belo Monte Dam would be 90 metres (300 ft) tall and 3,545 metres (11,631 ft) long, with a structural volume (embankments included) of 25,356,000 cubic metres (895,400,000 cu ft); while the Bella Vista would be 33 metres (108 ft) high and 351 metres (1,152 ft) long, with a structural volume of 239,500 cubic metres (8,460,000 cu ft). The Dos Canais Reservoir would have a normal capacity of 1,889,000,000 cubic metres (1,531,000 acre⋅ft), a normal surface area of 108 square kilometres (42 sq mi) and a normal elevation area of 97 metres (318 ft) above sea level. The Bela Vista Dam which serves as the complex's secondary spillway would have a maximum discharge capacity of 14,600 cubic metres per second (520,000 cu ft/s).[1]

Design flaw

Shortly before the planned installation of the dam's last (18th) turbine in November 2019, it was revealed that catastrophic failure of the dam was possible due to exposure of an unprotected area of the dam wall to wave action in the then prevailing low water level. In an 11 October 2019 Norte Energia report, the company's CEO requested more water from an intermediate reservoir to add to the dangerously low 95.2 meter water level.[50]

Power generation and distribution

The planned capacity of Belo Monte is listed at 11,233 MW. It is composed of the main Belo Monte Dam, and its turbine house with an installed capacity of 11,000 MW. The Pimental Dam which also includes a turbine house would have an installed capacity of 233.1 MW, containing 38.85 MW bulb turbines. The generation facility is planned to have 18 Francis turbines with a capacity of 611.11 MW each.[29]

In February 2011, Norte Energía signed contracts with:

- IMPSA worth $450 million to design and install by the fall of 2015 four Francis turbine generation units to provide 2,500 MW of power.[51]

- Andritz AG to provide three Francis turbines and the six bulb turbines, and the 14 excitation systems for the main power house and additional equipment for the Pimental power house.[52]

- Alstom worth $682.3 million to provide 7 Francis turbines, and 14 gas insulated substations for the facility.[29]

Capacity

Walter Coronado Antunes, the former Secretary of the Environment of the state of São Paulo, and ex-President of the state water and sanitation utility Sabesp, has said that the Belo Monte Dam Complex would be one of the least efficient hydro-power projects in the history of Brazil, producing only 10% of its 11,233 MW nameplate capacity between July and October (1,123 MW, and an average of only 4,419 MW throughout the year, or a 39% capacity factor).[53][54] According to the president of Brazil's Energy Research Company (EPE), 39% is "just a little below" Brazil's average of 55%. Normally, the capacity factor of hydroelectric power plants is between 30% and 80%, while wind power is typically between 20% and 40%.[55] According to a study by Eletrobras, even when at reduced capacities, Belo Monte would still have the capacity to supply the entire state of Para with electricity.[22]

Availability

Critics claim that the project would only make financial sense if the Brazilian government builds additional dam reservoirs upstream to guarantee a year-round flow of water, thus increasing the availability of generation. Supporters of the project point out that the seasonal minimum flow of the Xingu river occurs at a time when other Brazilian hydro plants are well supplied, so that no additional dams would have to be built. Reportedly, Brazil's National Council for Power Policies approved a resolution, previously sanctioned by then president Lula, that only one hydroelectric dam would be built on the Xingu. With one dam, critics do not see a cost-to-benefit ratio advantage and question the government's decision to construct only one.[56]

Additional upstream dams would directly or indirectly affect 25,000 indigenous people in the entire Xingu basin. Of particular note is the Altamira (Babaquara) Dam, which would flood an additional 6,140 square kilometres (2,370 sq mi) of reservoir, according to its original design.[57]

Developer

The project is developed by Norte Energia. The consortium is controlled by the state-owned power company Eletrobras, which directly (15%) and through its subsidiaries Eletronorte (19.98%) and CHESF (15%) controls a 49.98% stake in the consortium.[58]

In July 2010, the federal holding company Eletrobras stated that there were 18 partners and reported their adjusted share in the project:

- Eletronorte (subsidiary of Eletrobras) – 19.98%

- Eletrobras, state-owned company – 15%

- CHESF (subsidiary of Eletrobras) – 15%

- Bolzano Participacoes investments fund – 10%

- Gaia Energia e Participações (Bertin Group) – 9%

- Caixa Fi Cevics investments fund – 5%

- Construction firm OAS – 2.51%

- Queiroz Galvão, construction company – 2.51%

- Funcef pension fund – 2.5%

- Galvão Engenharia, construction company – 1.25%

- Contern Construções, construction company – 1.25%

- Cetenco Engenharia, construction company – 1.25%

- Mendes Junior, construction company – 1.25%

- Serveng-Civilsan, construction company – 1.25%

- J Malucelli, construction company – 1%

- Sinobras – 1%

- J Malucelli Energia, construction company – 0.25%

- SEPCO1, Siemens[59]

The Norte Energia consortium construction companies were reported to have originally held a 40% share.[60]

In April 2012 it was announced that a $146 million contract was signed between Norte Energia S.A. and a consortium consisting of ARCADIS logos (a subsidiary of ARCADIS) holding a 35% share, and Themag, Concremat, and ENGECORPS, who will provide their engineering services to the project.[61]

Economics

The dam complex is expected to cost upwards of $16 billion and the transmission lines $2.5 billion. The project is being developed by the state-owned power company Eletronorte, and would be funded largely by the Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES).[62] The project will also include substantial amounts of funding from Brazilian pension funds Petros, Previ, and Funcef. Private investors interested in the project include mining giants Alcoa and Vale (to power new mines nearby like the proposed Belo Sun gold mine[50]), construction conglomerates Andrade Gutierrez, Votorantim, Grupo OAS, Queiroz Galvão, Odebrecht and Camargo Corrêa, and energy companies GDF Suez and Neoenergia.

In 2006, Conservation Strategy Fund (CSF) analyzed different cost-benefit scenarios for Belo Monte as an energy project, excluding environmental costs. Initial benefits appeared marginal. When simulating energy benefits using a modeling system it became obvious that Belo Monte would require additional upstream dams to provide water storage for dry season generation. CSF concluded that Belo Monte would not be sustainable without the proposed Altamira (Babaquara) dam which would have a reservoir more than 10 times the size of Belo Monte's, flood 30 times the area submerged by Belo Monte, indigenous territories of the Araweté/Igarapé Ipixuna, Koatinemo, Arara, Kararaô, and Cachoeira Seca do Irirí natives.[63]

Due to the project's lack of economic viability and lack of interest from private investors, the government has had to rely on pension funds and lines of credit from BNDES that draw from the Workers' Assistance Fund, oriented towards paying the public debt, to finance the project; up to one-third of the project's official cost would be financed by incentives using public money.[64]

Alternatives

WWF-Brazil released a report in 2007 stating that Brazil could cut its expected demand for electricity by 40% by 2020 by investing in energy efficiency. The power saved would be equivalent to 14 Belo Monte hydroelectric plants and would result in national electricity savings of up to R$33 billion (US$19 billion).[65]

Ex-director of ANEEL Afonso Henriques Moreira Santos stated that large dams such as Belo Monte were not necessary to meet the government's goal of 6% growth per year. Rather, he argued that Brazil could grow through increasing its installed capacity in wind power, currently only at 400 MW.[66]

However, a study by the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, published in June 2011, criticised some of these alternative suggestions and defended the Belo Monte dam project. They state that compared to the estimated costs of alternative energies, the Belo Monte dam is cheaper both in economic and in socio-environmental costs.[67][68]

Environmental effects

The project is strongly criticized by indigenous people and numerous environmental organizations in Brazil plus organizations and individuals around the world.[69][70]

Belo Monte's 668 square kilometres (258 sq mi) of reservoir will flood 400 square kilometres (150 sq mi) of forest, about 0.01% of the Amazon forest.[71] Though argued to be a relatively small area for a dam's energy output, this output cannot be fully obtained without the construction of other dams planned within the dam complex.[12] The expected area of reservoir for the Belo Monte dam and the necessary Altamira dam together will exceed 6500 km2 of rainforest.[12]

The environmental impact assessment written by Eletrobras, Odebrecht, Camargo Corrêa, and Andrade Gutierrez listed the following possible adverse effects

- The loss of vegetation and natural spaces, with changes in fauna and flora;

- Changes in the quality and path of the water supply, and fish migration routes;

- Temporary disruption of the water supply in the Xingu riverbed for 7 months;

Incomplete environmental assessment

In February 2010, Brazilian environmental agency IBAMA granted an environmental license for the construction of the dam despite uproar from within the agency about incomplete information in the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) written by Eletrobras, Odebrecht, Camargo Corrêa, and Andrade Gutierrez.[72] Previously in October 2009, a panel composed of independent experts and specialists from Brazilian universities and research institutes issued a report on the EIA, finding "various omissions and methodological inconsistencies in the EIA..." Among the problems cited within the EIA were the project's uncertain cost, deforestation, generation capacity, greenhouse gas emissions and in particular the omission of consideration for those affected by the river being mostly diverted in the 100 km (62 mi) long "Big Bend" (Volta Grande).[73]

Two senior officials at IBAMA, Leozildo Tabajara da Silva Benjamin and Sebastião Custódio Pires, resigned their posts in 2009 citing high-level political pressure to approve the project.[74] In January 2011, IBAMA president Abelardo Azevedo also resigned his post. The previous president Roberto Messias had also stepped down, citing in April 2010 that it was because of pressure from both the government and environmental organizations.[22]

140 organizations and movements from Brazil and across the globe decried the decision-making process in granting the environmental license for the dams in a letter to Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva in 2010.[75]

Loss of biodiversity

The fish fauna of the Xingu river is extremely rich with an estimated 600 fish species and with a high degree of endemism.[76] The area either dried out or drowned by the dam spans the entire known world distribution of a number of species, e.g. the zebra pleco (Hypancistrus zebra), the sunshine pleco (Scobinancistrus aureatus), the slender dwarf pike cichlid (Teleocichla centisquama), the killifish Anablepsoides xinguensis and Spectrolebias reticulatus, and the Xingu dart-poison frog (Allobates crombiei). An independent expert review of the costs of the dam concluded that the proposed flow through the Volta Grande meant the river "will not be capable of maintaining species diversity", risking "extinction of hundreds of species".[48]

Greenhouse gas budget

The National Amazon Research Institute (INPA) calculated that during its first 10 years, the Belo Monte-Babaquara dam complex would emit 11.2 million metric tons of Carbon dioxide equivalent, and an additional 0.783 million metric tons of CO

2 equivalent would be generated during construction and connection to the national energy grid.[77] This independent study estimates greenhouse gas emissions of an amount that would require 41 years of optimal energy production from the Belo Monte Dam complex (including the now aborted Altamira Dam) in order to reach environmental sustainability over fossil fuel energy.[77]

Dams in Brazil emit high amounts of methane, due to the lush jungle covered by waters each year as the basin fills. Carbon is trapped by foliage, which then decays anaerobically with help from methanogens, converting the carbon to methane, which is a more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide. As a result, carbon emissions are emitted from the dam each year it is in operation. A 1990 study of the Curuá-Una Dam, also in Brazil, found that it pollutes 3.5 times more in carbon dioxide equivalent than an oil power plant generating an equal amount of electricity would;[78] not in the form of the CO2 atmospheric pollution associated with fossil fuel burning, but as the more dangerous methane emissions. Furthermore, the forest will be cleared before flooding of the area, so the CO2 and methane emissions calculated for the flooding of the forested area will be significantly undercut. In addition, a study on the Brazilian Tucuruí dam showed that the actual greenhouse gas emissions were a factor ten higher than its official calculations showed, and this dam is no exception; it is feared that the Belo Monte Dam calculations are also deliberately undercutting reality and that the flooding of its reservoir will create a similar situation.[79][80] If the dam builders cleared the forest beforehand, they would remove the organic matter from the reservoir floor and the dam would produce less of the greenhouse gas methane. However, in the case of Tucuruí, only the economically necessary forest was cut (10%, near the opening to the spillway) and the rest was left intact to be flooded by the reservoir. The contractors had sold the logging rights to the flooded area, but found the plot unviable in the short amount of time they had allocated before the area was set to be flooded. This forest has been decaying under the water through Methanogenesis and producing large amounts of greenhouse gases.

On the other hand, the energy generated by the dam for the next 50 years, at an average of 4419 MW, is 1.14 bboe (billion barrels of oil equivalent). This is approximately 9% of the proven oil reserves of Brazil (12.6 bbl[81]), or 2% of the total oil reserves of Russia (60 bbl[82]), or 5.5% of the proven oil reserves of the U.S. (21 bbl[83]).

Social effects

Although strongly criticized by indigenous leaders, the president of Brazil's EPE claims they have popular support for the dam. On 20 April 2010 Folha de Sao Paulo poll showed 52% in favor of the dam.[22][28][56] The dam will directly displace over 20,000 people, mainly from the municipalities of Altamira and Vitória do Xingu.[84] Two river diversion canals 500 metres (1,600 ft) wide by 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) long will be excavated. The canals would divert water from the main dam to the power plant. Belo Monte will flood a total area of 668 square kilometres (258 sq mi). Of the total, 400 square kilometres (150 sq mi) of flooded area will be forested land.[71] The river diversion canals will reduce river flow by 80% in the area known as the Volta Grande ("Big Bend"), where the territories of the indigenous Juruna and Arara people, as well as those of sixteen other ethnic groups are located.[73] While these tribes will not be directly impacted by reservoir flooding, and therefore will not be relocated, they may suffer involuntary displacement, as the river diversion negatively affects their fisheries, groundwater, ability to transport on the river and stagnant pools of water offer an environment for water-borne diseases, an issue that is criticized for not being addressed in the Environmental Impact Assessment.[73]

Among the 20,000 to be directly displaced by reservoir flooding, resettlement programs have been identified by the government as necessary for mitigation. Norte Energia have failed to obtain free, prior, and informed consent from the Juruna and Arara indigenous tribes to be impacted by Belo Monte.[85] The project would also attract an estimated 100,000 migrants to the area.[73] An estimated 18,700 direct jobs would be created, with an additional 25,000 indirect jobs to accommodate the surge in population.[22] However, only a fraction of the direct jobs will stay available after the project's completion, which critics have argued to spell economic disaster rather than economic prosperity.[22][73]

The influx of immigrants and construction workers has also led to increased social tension between groups. Indigenous groups report attacks and harassment, and in several occasions the destruction of property and the death of indigenous persons as a result from constructing and (illegal) logging activities.[86][87][88] External researchers indicate that the majority of the Belo Monte dam's energy output will be relegated towards the aluminium industry, and will not benefit the people living in the area.[12] However, Norte Energia released a clarification note stating their concern with the socioeconomic development of the area, including the promise to invest R$3.700 billion (1,300 million GBP) into various issues.[89]

IBAMA report

The IBAMA's environmental impact assessment has listed the following possible impacts:

- The generation of expectations towards the future of the local population and indigenous people;

- An increase in population and uncontrolled land occupation;

- An increase in the needs of services and goods, as well as job demand;

- A loss of housing and economic activities due to the transfer of population;

- Improvements on the accessibility of the region;

- Changes in the landscape, caused by the installation of support and main structures for the construction of the dam;

- Damage to the archaeological estates in the area;

- Permanent flooding of shelters in Gravura Assurini;

However, a clarification was released by the Brazilian authorities, in which it was deemed that the assured social and economic benefits, considered for the environmental redesign and the region's infrastructural developments, would outweigh the expected environmental damage.[90] Since the beginning of the project many environmental and human rights organizations have been protesting against the construction of the Belo Monte Dam. On 14 August 2012 the Brazil Federal Court halted the construction of the Belo Monte Dam on the basis that the government's authorization of the dam was unconstitutional. The government didn't hold constitutionally required meetings with indigenous communities affected by the dam before granting permission in 2005 to start with the construction.[91] This is against the Brazilian law and international human rights. However, Norte Energía, the company assigned with the construction of the Belo Monte Dam, has the possibility of an appeal to the Supreme Court.[92]

Human rights concerns

The attitude and treatment of the Brazilian government towards the affected indigenous groups is strongly criticised internationally. The UN Human Rights Council has published statements denouncing Brazil's careless construction methods,[93] and the International Labour Organization (ILO) likewise pointed out that the Brazilian state was in violation of ILO conventions (particularly the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, 1989 No 169)[94] – although mechanisms for international enforcement are lacking, and it would require a Brazilian court to apply the binding principles of the convention, which Brazil has ratified. Indigenous groups have questioned the government's actions over these events,[95] but their situation remains ignored by the authorities, as shown with the May 2011 Xingu Mission report of the CDDPH (Conselho de Defesa dos Direitos da Pessoa Humana),[96] of which several sections regarding accusations of human right violations were excluded by the Special Secretary for Human Rights, Maria do Rosário Nunes.[97]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Complexo Hidreletrico Belo Monte (Technical Details)" (in Portuguese). In the.zip file, see the file: Volume III Anexos\FICHA_TECNICA\Ficha_Tecnica_BMonte.pdf: Eletrobras. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- ↑ "A história de Belo Monte – Cronologia". Norte Energia (in Brazilian Portuguese). Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- ↑ Empresa de Pesquisa Energética (2010), Consumo nacional de energia elétrica cresce 8,4% em dezembro Archived 3 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Resenha Mensal do Mercado de Energia Elétrica (In Portuguese), Ano III, no. 28, Janeiro de 2010. Acessada em 2011-12-01.

- ↑ "Contrato de concessão №01/2010-mme-UHE Belo Monte" [Concession Contract № 01/2010 Belo Monte Dam] (PDF) (in Portuguese). ANEEL. 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- ↑ "Hydropower made up 66% of Brazil's electricity generation in 2020". www.eia.gov. Retrieved 15 November 2023.

- ↑ VIEIRA, Isabel (2011). "Diretora do Ibama diz que licença para Belo Monte teve por base cinco pareceres técnicos" Archived 31 December 2012 at archive.today|language= Portuguese. Agência Brasil, 31 January 2011

- ↑ RIMA (2009). "Relatório de Impacto Ambiental do Aproveitamento Hidrelétrico Belo Monte" Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Eletrobrás. May/2009.

- ↑ "Dilma inaugura usina hidrelétrica de Belo Monte — Portal Brasil". Archived from the original on 16 July 2016. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ↑ "A história de Belo Monte – Cronologia". Norte Energia (in Brazilian Portuguese). Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ↑ "Brazil unveils world's fourth biggest hydropower plant". Agência Brasil. 28 November 2019. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- 1 2 "AHE Belo Monte – Evolucado Dos Estudos" (in Portuguese). Eletrobras. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Fearnside, Phillip M. (12 January 2006). "Dams in the Amazon: Belo Monte and Brazil's Hydroelectric Development of the Xingu River Basin". Environmental Management. 38 (1): 16–27. Bibcode:2006EnMan..38...16F. doi:10.1007/s00267-005-0113-6. PMID 16738820. S2CID 11513197. Archived from the original on 20 January 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- 1 2 Sevá, Oswaldo (1 May 2005). "Tenotã–mõ Executive Summary". International Rivers. Archived from the original on 27 December 2010. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ↑ Carlos Alberto de Moya Figueira Netto; Hélio Costa de Barros Franco; Paulo Fernando Vieira Souto Rezende (2007). "AHE Belo Monte Evolução dos Estudos" [Belo Monte Dam Evolution Studies] (in Portuguese). Eletrobras. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ↑ "Belo Monte" (in Portuguese). Eletrobras. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ↑ "The Kayapo". BBC. 2008. Archived from the original on 3 December 2010. Retrieved 27 October 2010.

- ↑ Duffy, Gary (2 February 2010). "Brazil grants environmental licence for Belo Monte dam". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2 December 2010. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ↑ Strange, Hannah (2 February 2010). "Fury as Amazon rainforest dam approved by Brazil". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ↑ Wheatley, Jonathan (19 April 2010). "Brazil pushes ahead with Amazon power plan". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 11 September 2010. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ↑ Craide, Sabrina (27 April 2010). "Brazil's Big Contractors Looking for a Bigger Slice of Belo Monte's Action". Brazzil Mag. Archived from the original on 21 November 2010. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- ↑ Phillips, Tom (21 April 2010). "Awarding of Brazilian dam contract prompts warning of bloodshed". London: Guardian UK. Archived from the original on 20 January 2016. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Tug of War Over Belo Monte Dam". Latin Business Chronicle. 28 February 2011. Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ↑ Phillips, Tom (18 April 2010). "Avatar director James Cameron joins Amazon tribe's fight to halt giant dam". London: Guardian UK. Archived from the original on 12 April 2011. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ↑ "Suspensos leilão e licença de Belo Monte" [Court suspends license auction and Belo Monte]. UOL Notícias (in Portuguese). 14 April 2010. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- ↑ "Autorizado o leilão da usina Belo Monte pelo TRF" [Authorized the Belo Monte plant auction at TRF] (in Portuguese). Tribunal Regional Federal da Primeira Região. 16 April 2010. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ↑ "Recomendação Parecer 95/2010" [Recommendation 95/2010] (PDF). Ministério Público Federal do Pará (in Portuguese). International Rivers. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ↑ "Brazil: Despite Being Against Belo Monte, FUNAI Gives Assent to the Work". Indigenous Peoples Issues and Resources. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- 1 2 Barreto, Elzio (26 January 2011). "Brazil OKs building of $17 bln Amazon power dam". Reuters. Archived from the original on 22 December 2011. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- 1 2 3 "Alstom to provide equipment to Belo Monte hydro project in Brazil". HydroWorld.com. PennWell Corporation. 9 February 2011. Archived from the original on 12 July 2011. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ↑ Barrionuevo, Alexei (1 June 2011). "Brazil, After a Long Battle, Approves an Amazon Dam". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ↑ Brooks, Bradley (1 June 2011). "Brazil grants building license for Amazon dam". Bloomberg Businessweek. Archived from the original on 2 November 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- 1 2 Goy, Leo (26 February 2011). "Brazil court halts massive Amazon dam construction". Reuters. Archived from the original on 3 March 2011. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- 1 2 3 Fallon, Amy (26 February 2011). "Brazilian judge blocks plans for construction of Belo Monte dam". The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ↑ "Brazil court halts Amazon dam". Al Jazeera. 26 February 2011. Archived from the original on 28 February 2011. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ↑ "Amazon dam construction halted in Brazil". Malaysia Sun. 26 February 2011. Archived from the original on 2 March 2011. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- ↑ "Brazil judge blocks Amazon Belo Monte dam". BBC News. 26 February 2011. Archived from the original on 26 February 2011. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ↑ "Brazil court reverses Amazon Monte Belo dam suspension". BBC News. 3 March 2011. Archived from the original on 5 March 2011. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

- ↑ "Decision Allows for Forest Clearance and Start-Up of Dam Construction to Begin, Despite Violations of Human Rights and Environmental Legislation" (Press release). Amazon Watch. 5 March 2011. Archived from the original on 15 March 2011. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- ↑ Phillips, Tom (10 March 2011). "Belo Monte hydroelectric dam construction work begins". London: Guardian UK. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 2 April 2011.

- ↑ "Brazil judge halts work on Belo Monte Amazon dam". BBC News. 28 September 2011. Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- ↑ "Brazil court orders halt to work on $11 bln mega-dam". Agence France-Presse. 28 September 2011. Archived from the original on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- ↑ "Brazil court refuses to stop work on Amazon dam". Agence France-Presse. 9 November 2011. Archived from the original on 7 June 2012. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- ↑ Ministério Público de Federal (27 January 2012). "Embargos de declaracao proceso Belo Monte" (in Portuguese) (PDF). Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- ↑ Dow Jones Newswires (26 April 2012). "Brazilian Judge rules Belo Monte work stoppage illegal" (http://www.foxbusiness.com/news/2012/04/26/brazilian-judge-rules-belo-monte-work-stoppage-illegal). Retrieved 5 May 2012

- ↑ Watts, Jonathan (16 August 2012). "Belo Monte dam construction halted by Brazilian court". London: Guardian UK. Archived from the original on 4 August 2014. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ↑ "Brazil's Supreme Court orders resumption of work on mammoth dam in Amazon rainforest". The Washington Post. 28 August 2012. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- ↑ "Breaking: Brazilian court reinstates operating license for 11.2-GW Belo Monte hydroelectric plant". HydroWorld. 27 January 2016. Archived from the original on 27 May 2016. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- 1 2 "Experts Panel Assesses Belo Monte Dam Viability" (PDF). Survival International. October 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- ↑ "AHE Belo Monte" (in Portuguese). Eletronorte. p. 14. Archived from the original on 12 November 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- 1 2 Watts, Jonathan (8 November 2019). "Poorly planned Amazon dam project 'poses serious threat to life'". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ↑ "IMPSA secures $450MM contract for Belo Monte hydropower plant in Brazil". PennWell Corporation. 21 February 2011. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ↑ "Andritz to supply major equipment for Belo Monte hydropower plant" (Press release). Andritz AG. 14 February 2011. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ↑ Coronado Antunes, Walter (July 2010). "Crítica ao Aproveitamento Hidrelétrico Belo Monte" [Critics of the approval of the Belo Monte Hydroelectric Plant] (PDF). Jornal do Instituto de Engenharia (in Portuguese). Instituto de Engenharia (Brazilian Engineering Institute) (59): 8–9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 November 2010. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ↑ Hurwitz, Zachary (20 August 2010). "Belo Monte, "The Worst Engineering Project in the History of Brazil"". International Rivers. Archived from the original on 27 December 2010. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ↑ "Wind Power: Capacity Factor, Intermittency, and what happens when the wind doesn't blow?" (PDF). University of Massachusetts at Amhers: Renewable Energy Research Laboratory. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 October 2008. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- 1 2 "Brazilian government claims only a 'small minority' oppose Belo Monte dam". London: Guardian UK. 18 February 2011. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ↑ "Belo Monte Dam (Brazil : 2004-2006)". Conservation Strategy Fund. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 13 May 2007.

- ↑ Millikan, Brent (16 June 2010). "Lack of Private Sector in Belo Monte Consortium Signals Investor Concerns Over Financial Risks". International Rivers. Archived from the original on 28 December 2010. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ↑

"Han Jianhui (sepco1)". Facebook.

it is our honor to participate in the construction of the belo-monte project. we are responsible For the 1st, 2nd, 5th parts of the whole project, whose length totals 780 km. We have put a lot of resources into construction in order to guarantee the quality of our work. At the busiest time in the project, more than 3000 workers and 400 machines were in operation. Li Jinzhang (Chinese ambassador to Brazil) : the technique of ultra-high voltage power transmission has shown its strength during the construction and operation process. With high transmission efficiency and a small amount of waste, this project will reshape Brazil's network of power transmission as well as boost the development of nearby areas.

- ↑ "Belo Monte Hydro Project Consortium to Include 18 Partners". RenewableEnergyWorld.com. 16 July 2010. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ↑ ARCADIS (3 April 2012). "ARCADIS wins large contract for Belo Monte Hydroelectric Power Plant in Brazil" (http://www.arcadis.com/press/ARCADIS_WINS_LARGE_CONTRACT_FOR_BELO_MONTE_HYDROELECTRIC_POWER_PLANT_IN_BRAZIL.aspx#03.04.2012_ARCADISWINSLARGECONTRACTFORBELOMONT Archived 8 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine). Retrieved 5 May 2012

- ↑ "Belo Monte Dam". Amazon Watch. Archived from the original on 7 June 2007. Retrieved 13 May 2007.

- ↑ "Belo Monte Dam | Conservation Strategy Fund". Conservation Strategy Fund. 19 March 2009. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 27 October 2010.

- ↑ "Incentivos federais chegam a 1/3 do valor de Belo Monte," "Incentivos federais chegam a 1/3 do valor de Belo Monte - Terra". Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ↑ To download the report, see WWF-Brazil and Greenpeace, http://www.climatesolver.org/source.php?id=1252339%5B%5D

- ↑ Governo criará "monstro", diz ex-diretor da Aneel http://clippingmp.planejamento.gov.br/cadastros/noticias/2010/4/24/governo-criara-monstro-diz-ex-diretor-da-aneel%5B%5D

- ↑ de Castro, Nivalde J., da Silva Leite, André L., and de A. Dantas, Guilherme (June 2012). "Análise comparativa entre Belo Monte e empreendimentos alternativos: impactos ambientais e competitividade econômica" ( Archived 24 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Texto de Discussão do Setor Elétrico n.º 35, Rio de Janeiro (in Portuguese) (PDF). Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- ↑ ISRIA (2011). "Study shows that Belo Monte is the cheapest and cleanest alternative for power generation" Archived 24 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine. (PDF) Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ↑ Downie, Andrew (22 April 2010). "In Earth Day setback, Brazil OKs dam that will flood swath of Amazon". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 30 January 2011. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- ↑ "(Reuters) - Brazil is planning a massive hydroelectric dam in the Amazon region that has sparked controversy over its environmental impact and its displacement of residents". Reuters. 20 April 2010. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- 1 2 "Contrato de concessão №01/2010-mme-UHE Belo Monte" [Concession Contract № 01/2010 Belo Monte Dam] (PDF) (in Portuguese). ANEEL. 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- ↑ Duffy, Gary (2 February 2010). "Brazil grants environmental licence for Belo Monte dam". BBC. Archived from the original on 2 February 2010. Retrieved 2 February 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Summary and History of the Belo Monte Dam: Rainforest Foundation" (PDF). Summary and History of the Belo Monte Dam: Rainforest Foundation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 January 2011. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ↑ "Shame on Brazil: Stop the Amazon Mega-Dam Project Belo Monte". Huntington News Network. 11 March 2010. Archived from the original on 14 March 2010. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 April 2010. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Camargo M., GiarrizzoT. & Isaac V. (2004). "Review of the geographic distribution of fish fauna of the Xingu river basin, Brazil". Ecotropica 10: 123-147. PDF Archived 9 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Fearnside, Philip M. (28 February 2010). "Periódicos UFPA". Novos Cadernos Naea. 12 (2). doi:10.5801/ncn.v12i2.315. Archived from the original on 30 June 2010. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

- ↑ "Hydroelectric Power's Dirty Secret Revealed". Archived from the original on 10 July 2015. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- ↑ Fearnside, Phillip M. (2006). "Mitigation of Climate Change in the Amazon."(http://philip.inpa.gov.br/publ_livres/mss%20and%20in%20press/laurance-peres%20book%20ms.pdf Archived 7 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine) Book chapter in: W.F. Laurance and C.A. Peres (eds.), Emerging Threats to Tropical Forests. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- ↑ Fearnside, Phillip M. (1995). "Hydroelectric dams in the Brazilian Amazon as sources of greenhouse gases" (http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayAbstract?fromPage=online&aid=5935732 Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine). Environmental Conservation 22 (1):7-19. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- ↑ "US Energy Information Administration, Brazil Energy Data". Archived from the original on 31 July 2012. Retrieved 18 January 2011.

- ↑ "US Energy Information Administration, Russia Energy Data". Archived from the original on 28 December 2010. Retrieved 18 January 2011.

- ↑ "US Energy Information Administration, US Crude Oil Proved Reserves". Archived from the original on 5 August 2010. Retrieved 18 January 2011.

- ↑ Elizondo, Gabriel (20 January 2012). "Q&A: Battles over Brazil's biggest dam". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 29 January 2014. Retrieved 5 March 2014.

- ↑ "Report of UN Special Rapporteur James Anaya | James Anaya" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 January 2016. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ↑ Phillips, Tom (15 February 2012). "Amazon defenders face death or exile" (http://raoni.com/news-283.php Archived 24 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine). Retrieved 5 May 2012

- ↑ Watson, Fiona (10 January 2012). "Loggers invade tribal home of Amazon Indian child 'burned alive'" (http://www.survivalinternational.org/news/8006 Archived 16 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine). Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- ↑ Vilela d’Elia, André (27 February 2012). "Kapot Nhinore, o território ameaçado do Raoni e do povo Kayapó" (http://www.raoni.com/atualidade-290.php Archived 3 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine). (in Portuguese) Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- ↑ Norte Energia S.A. (14 September 2011). "Clarification note: The Guardian" (http://en.norteenergiasa.com.br/2011/09/14/clarification-note-the-guardian/ Archived 1 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine). Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- ↑ IBAMA (1 June 2011). "Ibama autoriza a instalação da Usina de Belo Monte" (http://www.ibama.gov.br/publicadas/ibama-autoriza-a-instalacao-da-usina-de-belo-monte Archived 22 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine). (in Portuguese) Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- ↑ "Welcome to nginx eaa1a9e1db47ffcca16305566a6efba4!185.15.56.1". www.adr.com. Archived from the original on 17 December 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- ↑ Watts, Jonathan (16 August 2012). "Belo Monte dam construction halted by Brazilian court". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 14 March 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ↑ Instituto Raoni (13 March 2012). "Violações dos direitos indigenas: o Conselho de Direitos Humanos da ONU Publica nossa declaração" (http://raoni.com/atualidade-298.php Archived 3 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine). (in Portuguese). Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- ↑ International Labour Organization (27 June 1989). "C169 Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, 1989" (). Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- ↑ Instituto Raoni (22 March 2012). "Carta aberta à Presidenta Dilma e à sociedade brasileira" (http://www.raoni.com/atualidade-307.php Archived 2 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine). (in Portuguese). Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- ↑ Conselho de Defesa dos Direitos da Pessoa Humana (24 May 2011). "Relatório de impressões sobre as violações dos direitos humanos na região conhecida como "Terra do Meio" no Estado do Pará" (http://www.xinguvivo.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/Relat%C3%B3rio-CDDPH.pdf Archived 9 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine). (In Portuguese) (PDF) Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- ↑ Glass, Verena (25 March 2012). "Entidades pedem missão do CDDPH para apurar violações de direitos humanos por Belo Monte" (http://raoni.com/actualites-311.php Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine). (in Portuguese). Retrieved 5 May 2012.

References

- Article from SocialStatus on the comparisons on how we view news in different mediums in reference to the Chief Raoni, Belo Monte Dam image.http://rhiannonbevan.wordpress.com/2013/04/02/news-vs-news/

External links

- Belo Monte hydroelectric complex

- AHE Belo Monte at Eletrobras

- Belo Monte campaign at International Rivers

- Belo Monte Dam at Amazon Watch

- Documentary

- Belo Monte backgrounder

- The rights and wrongs of Belo Monte 4 May 2013 The Economist

- Pontiroli Gobbi, Francesco. "Brazil's Belo Monte Dam project. Financial impact, indigenous peoples' rights & the environment" (PDF). Library Briefing. Library of the European Parliament. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- Building Belo Monte, a photographic documentary series

- Will The Belo Monte Dam Project Cause Harm On The Amazon River

- Brazilian Dam Causes Too Much or Too Little Water in Amazon Villages—Global Issues (1 April 2017)