Biterolf und Dietleib (Biterolf and Dietlieb) is an anonymous Middle High German heroic poem concerning the heroes Biterolf of Toledo and his son Dietleib of Styria. It tells the tale of Biterolf and Dietleib's service at the court of Etzel, king of the Huns, in the course of which the heroes defeat Etzel's enemies, including an extended war/tournament against the Burgundian heroes of the Nibelungenlied. As a reward for their services, Dietleib and Biterolf receive the March of Styria as a fief. The text is characterized by its comedic parody of the traditions of heroic epic.[1]

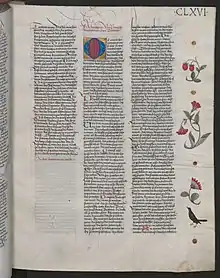

Biterolf und Dietleib is only attested in the Ambraser Heldenbuch (1504-1516), but it may have been composed in the thirteenth century. The poem is sometimes considered part of the cycle of legends about Dietrich von Bern: it is then either considered part of the so-called "historical" Dietrich poems, or else placed together in its own subgroup of Dietrich poems together with the Rosengarten zu Worms. More often, it is considered to be independent from the Dietrich cycle.[2][3]

Summary

Biterolf, the king of Toledo in Spain, hears of the grandeur of Etzel's court in Hungary, and decides to set out with twelve men to join that court, leaving Spain in secret. Near Paris he encounters Walther of Aquitaine, who had been a hostage of the Huns as a youth. At first, the two heroes fight, but soon they realize that Biterolf is the Walther's uncle. Walther then tells Biterolf of his experiences at Etzel's court. Biterolf continues his journey, but is forced repeatedly to fight against the lords through whose territory he travels, who demand a toll for him to pass through. He is, however, welcomed in Bechelarn by Etzel's margrave Rüdiger. Etzel is also welcoming and offers Biterolf gifts, but Biterolf refuses and also does not identify himself. Sometime later both Biterolf and Rüdiger fight a battle for the city of Gamaly, which belongs to the King of Prussia. Both heroes are captured, but Biterolf escapes and captures the lord of the castle where they are imprisoned, sends word to Etzel, and then conquers the city with an army and frees the other prisoners.

Some years later Biterolf's son Dietleib discovers his father's weapons and decides to set out in secret to find his father. Like his father, he is frequently attacked along the way, especially in Worms, where Hagen, Gernot, and Gunther attack him. He wounds all his opponents, however, who are amazed by skill at fighting given his youth. When he finally arrives at Etzel's court, Etzel's wife Helche takes him under her wing. Biterolf and Dietleib do not recognize each other, however. The heroes are soon called to battle, but Dietleib is told to stay behind due to his youth. He decides to secretly join the army however, and everyone is amazed at his prowess in battle. In the heat of the battle, he mistakes Biterolf for an enemy and they fight until Rüdiger separates the two. After the battle Rüdiger takes Biterolf aside and speaks to him, revealing that he has recognized Biterolf and Dietleib's identities, and the father and son are thus reunited. Biterolf had forced Rüdiger to promise not to reveal their identities to man or woman, but Rüdiger spreads the rumor throughout the court by telling a girl (neither man nor woman), who informs Etzel. Biterolf and Etzel then recognize each other as kings.

Dietleib now complains to Etzel about the attacks he endured from the Burgundians at Worms. Etzel calls together his army to avenge this dishonor and invades the Burgundians' kingdom, with the help of heroes such as Dietrich von Bern and others from Lombardy, Styria, Hungary, Austria, Poland, and Turkey. Upon receiving the declaration of war, Gunther calls together his own vassals from Saxony, Thuringia, Bohemia, Bavaria, Swabia, Lorrain, and the Netherlands. Etzel's army camps outside of Worms. Rüdiger then goes as a messenger to the Burgundians and the various heroes are introduced to each other and their intentions made clear. As his reward for being the messenger, Rüdiger is allowed to kiss all the ladies at the Burgundian court, and Brünhild gives Rüdiger a lance with a flag that he should carry into combat as a sign of his love for the ladies. The ladies of Worms also demand to choose the manner in which the heroes of the two armies should fight: either in a battle or in individual duals.

Rüdiger brings this message back to the Hunnish camp, where Hildebrand begins to organize the army for a large battle. Dietrich von Bern learns that he will be fighting against the troop led by Siegfried and becomes fearful due to the many stories about this hero. Hildebrand is forced to cajole Dietrich into fighting, evening fighting against him, until Dietrich is furious and ready to fight. Dietrich's vassal Wolfhart, meanwhile, laments that the Burgundians are well known for their jousts, whereas he knows little about this as he's only ever fought in wars. He wishes he had time to learn this form of entertainment while he's at Worms. Rüdiger therefore negotiates with the Burgundians to have a tournament rather than a battle, with the ladies of Worms as the audience. In the course of the tournament, however, several of the heroes on the Hunnish side are captured, including Wolfhart, and a change in the rules is negotiates so that Dietrich and his men can free them. This causes the tournament to turn into a real battle in which many are killed and wounded until night fall forces the fighting to end.

On the next day the battle begins as Hildebrand had planned it. The poet introduces the different troops that will fight as well as the various messengers and couriers traveling between them who will make sure that relatives on different sides avoid each other in battle. The battle lasts all day, with its climax being Dietrich's vassal Heime's decision to leave his troop to attack Siegfried. Siegfried, however, knocks Heime's famous sword Nagelring out of his hand, so that now the entire battle concerns the various armies fighting to recover the sword. Hildebrand finally recovers the weapon as darkness falls and the battle must be paused once more.

On the next day, it is decided to grant the armies a day of rest while only 86 of their leaders from each side fight. The two groups of 86 fight an evenly matched battle until Rüdiger succeeds in bringing his banner to the gates of Worms. He strikes a splinter from the wooden gate with his sword, and the ladies of Worms demand an end to the battle, to which the exhausted men agree. Gunther recognizes Dietleib as the greatest of warriors and invites the strangers into his court, where all are reconciled through various courtly festivities. Brünhild explains that she gave Rüdiger the flag in order to see the heroes demonstrate their abilities rather than in hopes of seeing the men kill each other. The various armies and their leaders then return home, and Heime is given back his sword. When Biterolf and Dietleib return to Etzel's court, Etzel grants Biterolf the March of Styria as a hereditary fief as a reward for his service. Biterolf then founds the city of Traismauer and resettles the people of Toledo there, where they found a new dynasty.[4]

Origins, transmission, and dating

Biterolf und Dietleib is typically dated to the middle of the thirteenth century. It is only transmitted in one manuscript, the Ambraser Heldenbuch. The poem's language shows typical elements of Styrian and Austrian dialects, indicating, like its content, that it was likely composed there.[5] The battle for the city of "Gamaly" in Prussia may reflect the two Prussian crusades undertaken by Ottokar II of Bohemia, who ruled Styria around that time.[6] Alternatively, its possible that the enfeoffment of Biterolf as lord of Styria and the resettlement of the Toledans refers to Rudolf von Habsburg's enfeoffment of his son with Styria in 1282, as well as the attempt by Alfonso X of Castile to claim the imperial throne instead of Rudolf.[7] Elisabeth Lienert finds these various attempts to connect the poem to historical events unconvincing.[1]

Like almost all German heroic poems, it is anonymous.[8] The second half of the Biterolf is closely related to Rosengarten zu Worms, a poem in the Dietrich cycle that similarly features battles between heroes of the Dietrich cycle and the Burgundians. The Biterolf even shares expressions and formulations with the Rosengarten, and it is most likely that the author of the Biterolf knew the Rosengarten and used it for his own composition.[9] The poem shows some similarities to the fragmentary Dietrich und Wenezlan as well, as both contain a campaign against Poland.[2]

Unlike most German heroic epics, the Biterolf is written in rhyming couplets rather than stanzas: this may indicate an attempt to allude to the genre of courtly romance, which was typically written in this form. Like the Nibelungenlied, the Biterolf is divided into chapters called âventiuren in the manuscript.[10] The poem may have been influenced by Wirnt von Gravenberg's Arthurian romance Wigalois.[11]

Interpretation

Although both Biterolf and Dietleib existed in the heroic tradition prior to composition of this poem, they do not appear to have had any particular story attached to them. Victor Millet suggests that it is therefore possible that the author of the Biterolf selected them as two heroes with whom he could write any story he wished.[12] The story may have been composed as a way of explaining Dietleib's description, already found in other poems, as von Stîre (of Styria), as well as playing the role of making Dietelib into a local hero for the Styrians. The poem, moreover, presents a fictional beginning of the creation of Styria as a polity: Dietleib appears as the founding hero of Styria.[13]

Biterolf and Dietleib's move to the court of Etzel is very similar to the magnetic power exercised on other knights and kings by the court of King Arthur in the romance tradition. Elisabeth Lienert explicitly compares Biterolf to Gahmuret from Wolfram von Eschenbach's Parzival as he travels east to Etzel, while comparing Dietleib to Parzival himself in his quest to seek his father. At the same time, the story seems to cite traditions also found in texts such as König Rother when Biterolf gives himself an alias at Etzel's court.[14] The story also represents a reversal of the story of Walter of Aquitaine: whereas Walter fled the Huns, Biterolf and Dietleib, his kinsmen, are both drawn to them. The battles fought by Dietleib against the Burgundians on his way to Etzel represent another citation of this tradition. Unlike in the Walter saga, however, no one is killed or wounded by these battles. The battle found by Biterolf against his son Dietleib is similarly reminiscent of the conflict in the Hildebrandslied and Jüngeres Hildebrandslied.[15] The battles at Worms are similarly full of allusions to or reversals of other heroic epics: Wolfhart, who is normally a hot-head, is shown to desire a courtly tournament, Rüdiger fulfills the role of messenger to the Burgundians just as in the Nibelungenlied, and Dietrich is shown to be afraid to fight, as in many poems. The battles, similarly, contain almost every known hero from German heroic tradition.[16] Lastly, the Huns and Burgundians reverse their roles from the end of the Nibelungenlied as the Huns go to Worms.[17] Elisabeth Lienert notes that these various citations and reversals mean that Biterolf und Dietleib is less a poem in the heroic tradition than a poem about the heroic tradition, with the Biterolf functioning as a sum of the heroic world as well as a parody of it. She characterizes the poem as using techniques of "montage" for a "literary game" ("literarisches Spiel") with the public's foreknowledge of the heroic tradition.[14]

Werner Hoffmann notes that the Biterolf appears to be set before any of the large conflicts of the Nibelungenlied or the historical Dietrich poems: there is no enmity between Brünhild and Kriemhild, Ermenrich supports Dietrich, the hostile Saxon kings from the Nibelungenlied support the Burgundians, etc. Hoffmann suggests that the work presents a sort of utopian vision of the time before these great conflicts and battles, in which reconciliation and recompense are possible. The poet also contrasts this utopian world critically with his own present.[18] Lienert nevertheless notes that the poem is full of foreshadowing of the future catastrophes for an audience which knew the heroic material: the poem is both a prehistory of the Nibelungenlied and Dietrich cycle, but it is also a less destructive alternative to the events in those texts. [19] The poem is also characterized by its at times ironic tone and critical distance to the story, which allows the narrative to play with elements of the heroic tradition. Victor Millet also notes that the poem's descriptions are unusually realistic, as is its geography. The text likely provided many potential points of identification for an Austrian audience at the end of the thirteenth century.[20] The text underlines the importance of kinship by expanding the role of kinship relations and their role in preventing conflict and effecting reconciliation.[17]

Notes

- 1 2 Lienert 2015, p. 142.

- 1 2 Lienert 2015, p. 145.

- ↑ Heinzle 1999, p. 179.

- ↑ Millet 2008, pp. 372–374.

- ↑ Millet 2008, p. 372.

- ↑ Hoffmann 1974, p. 178.

- ↑ Millet 2008, p. 378.

- ↑ Hoffmann 1974, pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Heinzle 1999, pp. 179–180.

- ↑ Hoffmann 1974, pp. 178–179.

- ↑ Hoffmann 1974, p. 179.

- ↑ Millet 2008, pp. 374–375.

- ↑ Lienert 2015, p. 142, 145.

- 1 2 Lienert 2015, p. 146.

- ↑ Millet 2008, pp. 375–376.

- ↑ Millet 2008, pp. 376–377.

- 1 2 Lienert 2015, p. 148.

- ↑ Hoffmann 1974, pp. 181–183.

- ↑ Lienert 2015, pp. 147–148.

- ↑ Millet 2008, pp. 377–378.

References

- Curschmann M (1977). "Biterolf und Dietleib". In Ruh K, Keil G, Schröder W (eds.). Die deutsche Literatur des Mittelalters. Verfasserlexikon. Vol. 1. Berlin, New York: Walter De Gruyter. cols 879-883. ISBN 978-3-11-022248-7.

- Gillespie, George T. (1973). Catalogue of Persons Named in German Heroic Literature, 700-1600: Including Named Animals and Objects and Ethnic Names. Oxford: Oxford University. ISBN 9780198157182.

- Haymes, Edward R.; Samples, Susan T. (1996). Heroic legends of the North: an introduction to the Nibelung and Dietrich cycles. New York: Garland. pp. 89–91. ISBN 0815300336.

- Heinzle, Joachim (1999). Einführung in die mittelhochdeutsche Dietrichepik. Berlin, New York: De Gruyter. pp. 179–180. ISBN 3-11-015094-8.

- Hoffmann, Werner (1974). Mittelhochdeutsche Heldendichtung. Berlin: Erich Schmidt. pp. 178–183. ISBN 3-503-00772-5.

- Lienert, Elisabeth (2015). Mittelhochdeutsche Heldenepik. Berlin: Erich Schmidt. pp. 142–149. ISBN 978-3-503-15573-6.

- Millet, Victor (2008). Germanische Heldendichtung im Mittelalter. Berlin, New York: de Gruyter. pp. 371–378. ISBN 978-3-11-020102-4.

External links

Facsimiles

- Ambraser Heldenbuch, Vienna. (Sole surviving MS. Biterolf begins at image 349)