Laurin or Der kleine Rosengarten (The Small Rose Garden) is an anonymous Middle High German poem about the legendary hero Dietrich von Bern, the counterpart of the historical Ostrogothic king Theodoric the Great in Germanic heroic legend. It is one of the so-called fantastical (aventiurehaft) Dietrich poems, so called because it more closely resembles a courtly romance than a heroic epic. It likely originates from the region of South Tyrol, possibly as early as 1230, though all manuscripts are later.[1]

The poem has five extant versions. In each, it concerns Dietrich's fight against the dwarf King Laurin, which takes place when Dietrich and Witege destroy Laurin's magical rose garden. The heroes are subsequently invited into Laurin's kingdom inside a mountain when it is discovered that Laurin has kidnapped and married the sister of Dietleib, one of Dietrich's heroes. Laurin betrays the heroes and imprisons them, but they are able to defeat him and save Dietleib's sister. The different versions depict Laurin's fate differently: in some, he becomes a jester at Dietrich's court, in others the two are reconciled and become friends.

The Laurin was one of the most popular legends about Dietrich. Beginning in the fifteenth century, it was printed both as part of the compendium of heroic poems known as the Heldenbuch and independently, and continued to be printed until around 1600. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, a variant of the poem was reimagined as a folk saga and became part of South Tyrolean popular folklore.

Summary

The Laurin exists in several versions (see "Transmission, versions, and dating" below). The oldest version of the tale (the so-called elder Vulgate version (ältere Vulgatversion), which the "Dresdner version" follows closely, begins with a conversation between Witige and Hildebrand. Witige says that Dietrich is the greatest hero of all time; Hildebrand objects that Dietrich has never experienced a twergenâventiure (dwarf-adventure). At that point Dietrich walks in and is very angered by Hildebrand's private criticism. Hildebrand tells Dietrich where he can find such an adventure: the dwarf king Laurin has a rose-garden in the Tyrolian forest. He will fight any challenger who breaks the thread surrounding his rose garden. Dietrich and Witige immediately set off to challenge Laurin; Hildebrand and Dietleib follow secretly behind. Upon seeing the beautiful rose-garden, Dietrich relents and decides that he does not want to harm anything so lovely. Witige, however, says that Laurin's pride must be punished, and not only breaks the thread, but tramples the entire rose garden. Almost immediately the dwarf Laurin, armed so wonderfully that Witige mistakes him for Michael the Archangel, appears, and demands the left foot and right hand of Witige as punishment for the destruction of the garden. He fights and defeats Witige, but Dietrich then decides that he cannot allow his vassal to lose his limbs, and fights Laurin himself. Initially, Dietrich is losing, but Hildebrand arrives and tells Dietrich to steal the dwarf's cloak of invisibility (helkeplein[2][4][lower-alpha 1]) and strength-granting belt[8][lower-alpha 2] then fight him on foot (the dwarf had been riding a deer-sized horse) wrestling him to the ground. Laurin, now defeated, pleads for mercy, but Dietrich has become enraged and vows to kill the dwarf. Finally, Laurin turns to Dietleib, informing him he had kidnapped and married the hero's sister Künhilt, so that he was now Dietleib's brother-in-law. Dietleib hides the dwarf and prepares to fight Dietrich, but Hildebrand makes peace between them.[10][11]

Dietrich and Laurin are reconciled, and Laurin invites the heroes to his kingdom under the mountain. All are enthusiastic except Witige, who senses treachery. In the mountain they are well received, and Dietleib meets Künhilt. She tells him she is being treated well and that Laurin has only one fault: he is not Christian. She wants to leave. Meanwhile, Laurin, after a feast, confides to Dietleib's sister that he wishes to avenge himself on the heroes. She advises him to do so. He drugs Witige, Hildebrand, and Dietrich and throws them into a dungeon. He tries to commit Dietleib to join his side, but locks him in a chamber when the hero refuses. Künhilt steals the stones that light the mountain and releases Dietleib. They then deliver weapons to the other heroes, and they begin a slaughter of all the dwarves in the mountain. In the end Laurin is taken as a jester back to Bern (Verona).[12]

In the "younger Vulgate version", the story of how Laurin kidnapped Dietleib's sister is told: he used a cloak of invisibility. Dietleib then goes to Hildebrand and reports the kidnapping. The two heroes set off, encountering a wild man who has been banished by Laurin. The wild man tells Hildebrand about Laurin and his rose garden, after which the heroes go to Bern. There follows the story as told in the older version. At the end, however, it is added that Dietrich accompanies Dietleib and his sister to Styria, where they stay with Dietleib's father Biterolf.[12]

In the so-called "Walberan" version, Laurin surrenders to Dietrich during their battle in the mountain. As Wolfhart and Witege prepare to slaughter all the inhabitants of the mountain, Laurin begs for mercy. Dietrich initially refuses, but Künhilt, Hildebrand, and Dietleib convince him to stop the killing. Laurin is taken as a prisoner to Bern, while the dwarf Sintram becomes Dietrich's vassal in command of the mountain. Once the heroes have returned to Bern, Künhilt begs Dietrich to treat Laurin well, as he has treated her well, and to convert him to Christianity. She is married to an unnamed noble and disappears from the story. Sintram, however, is disloyal, and sends for help from other dwarfs. Laurin's relative Walberan assembles a large army and declares war on Dietrich. Laurin tells Walberan's messengers that he is being treated well and begs Walberan not to damage Dietrich's lands. Walberan does as he is asked, but marches to Bern. Laurin attempts to negotiate with Walberan on Dietrich's behalf, and Walberan announces he and select warriors will fight Dietrich and his heroes in single combat. When Walberan fights Dietrich, Walberan is about to defeat Dietrich when Laurin and Laurin intervene—they reconcile Dietrich and the dwarf, and the poem ends with a courtly feast.[13]

The "Pressburg version" appears to parody Laurin: Hildebrand tells Dietrich about Laurin during a feast at carnival. Dietrich sets out with Hildebrand, Dietleib, Witege, Siegfried, and Wolfhart, before the text breaks off.[14]

Transmission, versions, and dating

The Laurin is transmitted in at least eighteen manuscripts, dating from the fourteenth century until the beginning of the sixteenth century, and in eleven printings dating from 1479 to 1590.[15] The text was first composed some time before 1300; Heinzle suggests it may have been composed before 1230, as it appears that Albrecht von Kemenaten may have known it when he composed his own poem about Dietrich and a dwarf king, Goldemar.[16] The poem may have been composed in Tyrol.[16] Victor Millet does not believe that it is possible to say when in the twelfth century and where the poem was composed.[17] Like almost all German heroic poems, it is anonymous,[18] but the "younger Vulgate version" claims the fictional poet Heinrich von Ofterdingen—who sings about Dietrich in a continuation to the poem Wartburgkrieg—as its author.[19]

There are five overarching versions, but due to the immense variability of the fantastical Dietrich poems, each manuscript can also be considered a version within these overarching five.[20] The five overarching versions are: the so-called "older Vulgate version" (ältere Vulgatversion); the "younger Vulgate version" (jüngere Vulgatversion), which can be further split into versions a and b; the "Walberan" version; the Dresdner Laurin; and the Pressburger Laurin.[21] The poem was also translated into Czech and Danish.[22]

Manuscripts with the older Vulgate version:

- L3 (P, p): Graf von Schönbornsche Schlossbibliothek Pommersfelden, Cod. 54. Paper, middle of fourteenth century, from Erfurt(?). Contains various poems in rhyming couplets, including the Rosengarten zu Worms and Laurin.[23]

- L4 (H, h): Staatsbibliothek Berlin, Ms. germ. 8° 287, Fragment I. Fragment of a parchment manuscript, fourteenth century, Middle German.[24]

- L5 (f): Stadt- und Universitätsbibliothek Frankfurt am Main, Ms. germ. 4° 2. Paper, second half of the fourteenth century, Rhine Franconian dialect. Contains various texts in rhyming couplets, including the Rosengarten and Laurin.[24]

- L6 (b): Öffentliche Bibliothek der Stadt Basel, Cod. G2 II 73. Paper, first half of the fifteenth century, from Basel(?).[24]

- L7 (Dess.): Stadtbibliothek Dessau, Hs. Georg. 224 4°. Paper, 1422, from Trier. Contains various poems in rhyming couplets, including the Rosengarten and Laurin.[24]

- L8 (m): in two libraries: Bayerische Staatsbibliothek Munich, Cgm. 811, and Staatsbibliothek Berlin, Ms. germ. 8° 287, Fragment II. Paper, second quarter of the fifteenth century, from Wemding. In poor condition with great loss of text.[25]

- L9 (v): Österreichische Nationalbibliothek Vienna, Cod. 2959. Paper, middle of fifteenth century, Bavarian. Collection of didactic love poems, but also includes Laurin.[26]

- L10 (w): Österreichische Nationalbibliothek Vienna, Cod. 3007. Paper, 1472, Silesian dialect. Contains various poetic, pragmatic, and didactic texts. Contains the ending of Laurin according to the younger vulgate version.[26]

- L13 (z): Domherrenbibliothek Zeitz, Cod. 83. Paper, fifteenth century, from Merseburg or Zeitz. Contains a Latin grammar and various German texts.[26]

- L15 (r): Bayerische Staatsbibliothek Munich, Cgm. 5919. Paper, beginning of sixteenth century, from Regensburg. Contains both pragmatic and poetic texts, including the Wunderer and Laurin.[26]

- L16: Österreichische Nationalbibliothek Vienna, Cod. 636. Parchment. Contains Latin text with a pen trial writing Laurin, probably written in the early fourteenth century.[26]

- L17: vanished, possibly Bavarian parchment manuscript, probably from the fourteenth century. Contained Laurin and the Nibelungenlied, possibly other texts.[27]

- L18: Biblioteka Jagiellońska, Krakow, Berol. ms. germ. 4° 1497. Paper, fifteenth century, in Upper German or Middle German. Contains spiritual texts and the Rosengarten and Laurin.[27]

Younger vulgate version:

- L12 (s): Heldenbuch of Diebolt von Hanowe. Formerly Strasbourg City/Seminary Library, destroyed 1870.[28][26]

It is also found in several printings. The Younger vulgate version b (a metrical and stylistic reworking) is found in various printings after 1555.[29]

The "Walberan" version:

- L1 (K): Arnamagnæanske Institut Copenhagen, AM 32 fol. Parchment, beginning of fifteenth century, from Venice in Bavarian dialect.[15]

- L2 (M): formerly Archive of the Historischer Verein von Oberbayern, Munich, Manuscript Cahier I von 4° Nr. 6. Lost.[15]

The Dresdner Laurin:

- L11 (ß): Dresdner Heldenbuch. Sächsische Landesbibliothek Dresden, Msc. M 201. Paper, 1472, from Nuremberg(?).[26][30][31]

The Pressburger Laurin:

Genre and interpretation

The choice to compose the poem in rhyming couplets rather than the stanzaic form typical for German heroic poetry means that the Laurin is written in the form typical of courtly romance.[17] The manner in which Dietrich sets out to fight Laurin is also very reminiscent of that genre, while the destruction of the garden has parallels to Chrétien de Troyes's Yvain and Hartmann von Aue's Iwein.[32] In this context, Dietrich's near refusal to spare Laurin must appear very negative, as must Dietrich and his heroes' newfound respect for Laurin once they discover he has kidnapped Künhilt.[33] Laurin himself indicates that he considers the destruction of his rose garden a breech of law, by which Witege especially is placed in a bad light.[34] The poem can be seen to deal with the senselessness of such knightly adventure.[35] Nevertheless, Laurin's characterization becomes increasingly negative as the poem progresses, although he is never shown to be entirely evil.[36] The various reworkings try to solve some of these ambiguities: in the Dresdner version, Laurin appears evil from the beginning; in the Walberan version, the humanity and dignity of the dwarf is instead placed in the foreground, causing Dietrich to spare him and suggesting that Dietrich was wrong to attack the rose garden.[37]

Metrical form

Except for the Dresdner Laurin, all versions of Laurin are composed in rhyming couplets. The "Dresdner Laurin" is composed in a variation of the "Hildebrandston" known as the "Heunenweise" or "Hunnenweise" (the Hunnish melody), in which there are rhymes at a mid-line caesura. Each line consists of three metrical feet, a caesura, then three additional feet.[38] Due to the survival of late medieval melodies among the Meistersingers, it is possible to sing these stanzas in the traditional manner of German heroic poetry.[38] This creates the following rhyme scheme: a||ba||bc||dc||d. Heinzle prints the following example from the Dresdner Laurin:[39]

Laurein der sweig stille; a || do sprach die kongein gemait: b

'vil edler konick, ich wille a || gewynen euch ein gelait, b

so komen wir hin ausse. c || sol wir gefangen sein? d

wir habent nimant dausse, c || weder zwerg noch zwergellein.' d

The stanza can also be understood to be made up of eight short verses, taking the caesuras as line endings.[40]

Relation to the oral tradition

A connection exists between this story and a Tyrolian Ladino folk-story in which the rose garden is the source of the morning-glow on the Alps, localized at the Rosengarten group.[41] Heinzle, however, while not dismissing this theory entirely, believes that, since this story is only attested from the 17th century onward, it is more likely to have been influenced by the text than the other way around.[42] Others have attempted to connect the rose garden to a cult of the dead, which Heinzle dismisses entirely.[43] A rose garden also plays an important role in another Dietrich poem, the Rosengarten zu Worms, which may have been inspired by Laurin.[44]

The first element of Laurin's name (Laur) may be derived from Middle High German lûren, meaning to deceive.[45] Alternatively, it may derive from a root *lawa- or *lauwa- meaning stone, also found in the name Loreley.[45]

Laurin is also connected to a legend about Dietrich's death. In the continuation to the Wartburgkrieg known as "Zebulons Buch," Wolfram von Eschenbach sings that Laurin told Dietrich that he only had fifty years to live. Laurin's cousin Sinnels, however, could allow Dietrich to live a thousand years. Dietrich and Laurin then jump into a fiery mountain (i.e. volcano) in order to reach Sinnels.[46] The tale is reminiscent of a story told of the historical Theoderic the Great by Pope Gregory the Great: Gregory reports that the soul of Theoderic was dropped into Mount Etna for his sins.[47] An unnamed dwarf is also responsible for taking Dietrich away after the final battle at Bern in the Heldenbuch-Prosa, telling him "his kingdom is no longer in this world."[48]

Medieval reception and modern legacy in South Tyrol

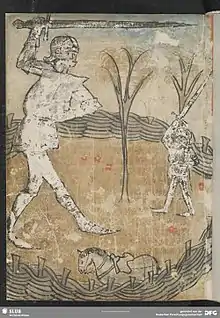

Laurin was a very popular text in the Middle Ages. Liechtenstein Castle in South Tyrol was decorated with frescoes based on the poem around 1400. Laurin's influence also extended beyond the German-speaking area. The Walberan manuscript L1, for instance, was likely produced by the German colony of merchants at Venice. The poem was translated into Czech in 1472, Danish around 1500, and printed in Middle Low German in 1560. The parallels to Walberan in Zebulons Buch discussed above also show an earlier reception of the poem in the thirteenth century.[49] The Jüngere Vulgatfassung continued to be printed in the early modern period, both as part of the printed Heldenbuch and separately.[29]

Through the rediscovery of the Laurin in the nineteenth century, the story of Dietrich and the dwarf king came to have a special meaning in the then Austrian region of South Tyrol, especially due to the works of travel journalist and saga-researcher Karl Felix Wolff.[50] In 1907, a Laurin fountain was erected in Bozen, showing Dietrich wrestling Laurin to the ground. After South Tyrol became part of Italy, the fountain survived in its original form until 1934, when unidentified persons likely acting under the inspiration of the Italian Fascist government, destroyed the fountain as a symbol of German supremacy over Italy.[51] When the fountain was finally rebuilt, conflict ignited over the fountain as a supposed symbol of the Germanic conquest of the original Ladin speaking inhabitants of the area.[52]

Editions

- Holz, Georg, ed. (1897). Laurin und der kleine Rosengarten. Halle a.d. Saale: Niemeyer. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- Lienert, Elisabeth; Kerth, Sonja; Vollmer-Eicken, eds. (2011). Laurin (2 vols). Berlin, Boston: de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110258196. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

Translations

Into German:

- Tuczay, Christa (1999). Die Aventiurehafte Dietrichepik: Laurin und Walberan, der Jüngere Sigenot, das Eckenlied, der Wunderer. Göppingen: Kümmerle. ISBN 3874528413. (translates the Walberan version)

Into English:

- Weber, Henry William; Jamieson, Robert; Scott, Walter (1814). "Of the Little Garden of Roses, and of Laurin, King of the Dwarfs". Illustrations of Northern Antiquities from the earlier Teutonic and Scandinavian Romances; being an abstract of the Book of Heroes and Nibelungen Lay; with translations from the old German, Danish, Swedish, and Icelandic languages; with notes and dissertations. Edinburgh: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown. pp. 149-166. Retrieved 8 April 2018. (Translates the younger vulgate version)

- The Saga of Didrik of Bern, with The Dwarf King Laurin. Translated by Cumpstey, Ian. Skadi Press. 2017. ISBN 0-9576-1203-6. (translates the Danish adaptation of Laurin)

Explanatory notes

References

- Citations

- ↑ Lienert 2015, pp. 130–131.

- ↑ Riedl, Steve (1913). Wissende - Helden - Schadenstifter: Zu den Figuren der aventiurehaften Dietrichepik. LIT Verlag Münster. pp. 233–. ISBN 9783643151544.

- ↑ Lienert, Kerth & Vollmer-Eicken 2011, p. 226.

- ↑ Dresdner Laurin Str. 126, 3. helkepllein[3]

- 1 2 Johnson (1990), p. 216.

- ↑ Schönfelder, Kniebe & Müller (1920), p. 208.

- ↑ Lienert, Kerth & Vollmer-Eicken (2011), p. 114.

- ↑ Laurin (ältere Vulgatversion) v. 1089, gurthel, var. gurtelein.[7]

- ↑ Schönfelder, Kniebe & Müller (1920), p. 209.

- ↑ Heinzle 1999, p. 156.

- ↑ Heinzle (1985), col 627.

- 1 2 Heinzle 1999, p. 157.

- ↑ Heinzle 1999, pp. 157–158.

- ↑ Heinzle 1999, pp. 158–159.

- 1 2 3 Heinzle 1999, p. 145.

- 1 2 Heinzle 1999, p. 159.

- 1 2 Millet 2008, p. 354.

- ↑ Hoffmann 1974, pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Heinzle 1999, pp. 161–162.

- ↑ Heinzle 1999, pp. 159–160.

- ↑ Heinzle 1999, pp. 152–153.

- ↑ Heinzle 1999, p. 155.

- ↑ Heinzle 1999, pp. 145–146.

- 1 2 3 4 Heinzle 1999, p. 146.

- ↑ Heinzle 1999, pp. 146–147.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Heinzle 1999, p. 147.

- 1 2 Heinzle 1999, p. 148.

- ↑ Heinzle 1999, p. 129.

- 1 2 Heinzle 1999, pp. 148–152.

- ↑ Heinzle 1999, p. 44.

- ↑ Heinzle 1999, p. 111.

- ↑ Millet 2008, pp. 358–359.

- ↑ Millet 2008, p. 359.

- ↑ Hoffmann 1974, pp. 212–213.

- ↑ Heinzle 1999, pp. 168–169.

- ↑ Lienert 2015, p. 133.

- ↑ Millet 2008, pp. 359–360.

- 1 2 Heinzle 1999, p. 154.

- ↑ Heinzle 1999, p. 153.

- ↑ Hoffmann 1974, p. 209.

- ↑ Hoffmann 1974, pp. 210–211.

- ↑ Heinzle 1999, pp. 163–165.

- ↑ Heinzle 1999, p. 165.

- ↑ Heinzle 1999, p. 183.

- 1 2 Gillespie 1973, p. 89.

- ↑ Heinzle 1999, p. 161.

- ↑ Heinzle 1999, p. 8.

- ↑ Heinzle 1999, pp. 47–48.

- ↑ Lienert 2015, pp. 133–134.

- ↑ Heinzle 1999, p. 162.

- ↑ Heinzle 1999, pp. 162–163.

- ↑ Heinzle 1999, p. 163.

- Bibliography

- Gillespie, George T. (1973). Catalogue of Persons Named in German Heroic Literature, 700–1600: Including Named Animals and Objects and Ethnic Names. Oxford: Oxford University. ISBN 9780198157182.

- Handschriftencensus (2001). "Gesamtverzeichnis Autoren/Werke: 'Laurin'". Handschriftencensus. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- Heinzle J (1985) [1977]. "Laurin". In Ruh K, Keil G, Schröder W (eds.). Die deutsche Literatur des Mittelalters. Verfasserlexikon. Vol. 5. Berlin, New York: Walter De Gruyter. cols 625–630. ISBN 978-3-11-022248-7.

- Heinzle, Joachim (1999). Einführung in die mittelhochdeutsche Dietrichepik. Berlin, New York: De Gruyter. pp. 58–82. ISBN 3-11-015094-8.

- Hoffmann, Werner (1974). Mittelhochdeutsche Heldendichtung. Berlin: Erich Schmidt. pp. 202–209. ISBN 3-503-00772-5.

- Johnson, Sidney M. (1990), "Medieval German Dwarfs: A Footnote to Gottfried's Melot", Gottfried Von Strassburg and the Medieval Tristan Legend: Papers from an Anglo-North American Symposium, Arthurian studies 2 3, D.S. Brewer, pp. 209–222, ISBN 9780854571468

- Lienert, Elisabeth (2015). Mittelhochdeutsche Heldenepik. Berlin: Erich Schmidt. pp. 130–134. ISBN 978-3-503-15573-6.

- Millet, Victor (2008). Germanische Heldendichtung im Mittelalter. Berlin, New York: de Gruyter. pp. 332–370. ISBN 978-3-11-020102-4.

- Schönfelder, Emil; Kniebe, Rudolf; Müller, Peter, eds. (1920), "24. Aus dem Laurin", Lesebuch zur Einführung in die Ältere deutsche Dichtung, vol. 1, Frankfurt-am-Main: Diesterweg, pp. 206–209

External links

Facsimiles

- Dresden, State Library, Mscr. M 201, The Dresden Heldenbuch (MS L11)

- Das büechlin saget von dem rosengarten künig Laurin (1500 printing, Strasbourg)