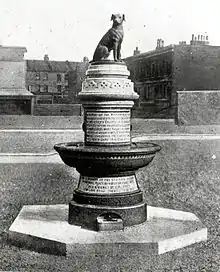

Top: The Brown Dog by Joseph Whitehead, erected in 1906 in Battersea's Latchmere Recreation Ground and presumed destroyed in 1910.Bottom: A new statue by Nicola Hicks was erected in Battersea Park in 1985. | |

| Date | February 1903 – March 1910 |

|---|---|

| Location | London, England, particularly Battersea |

| Coordinates | 51°28′19″N 0°9′42″W / 51.47194°N 0.16167°W (position of original statue) |

| Theme | Animal testing |

| Key people | |

| Trial | Bayliss v. Coleridge (1903) |

| Royal commission | Second Royal Commission on Vivisection (1906–1912) |

The Brown Dog affair was a political controversy about vivisection that raged in Britain from 1903 until 1910. It involved the infiltration of University of London medical lectures by Swedish feminists, battles between medical students and the police, police protection for the statue of a dog, a libel trial at the Royal Courts of Justice, and the establishment of a Royal Commission to investigate the use of animals in experiments. The affair became a cause célèbre that divided the country.[1]

The controversy was triggered by allegations that, in February 1903, William Bayliss of the Department of Physiology at University College London performed an illegal vivisection, before an audience of 60 medical students, on a brown terrier dog—adequately anaesthetized, according to Bayliss and his team; conscious and struggling, according to the Swedish activists. The procedure was condemned as cruel and unlawful by the National Anti-Vivisection Society. Outraged by the assault on his reputation, Bayliss, whose research on dogs led to the discovery of hormones, sued for libel and won.[2]

Anti-vivisectionists commissioned a bronze statue of the dog as a memorial, unveiled on the Latchmere Recreation Ground in Battersea in 1906, but medical students were angered by its provocative plaque—"Men and women of England, how long shall these Things be?"—leading to frequent vandalism of the memorial and the need for a 24-hour police guard against the so-called anti-doggers.[3] On 10 December 1907, hundreds of medical students marched through central London waving effigies of the brown dog on sticks, clashing with suffragettes, trade unionists and 300 police officers, one of a series of battles known as the Brown Dog riots.[4]

In March 1910, tired of the controversy, Battersea Council sent four workers accompanied by 120 police officers to remove the statue under cover of darkness, after which it was reportedly melted down by the council's blacksmith, despite a 20,000-strong petition in its favour.[5] A new statue of the brown dog, commissioned by anti-vivisection groups, was erected in Battersea Park in 1985.[6]

On 6 September 2021, the 115th anniversary of when the original statue was unveiled, a new campaign was launched by author Paula S. Owen to recast the original statue.[7]

Background

Cruelty to Animals Act 1876

There was significant opposition to vivisection in England, in both houses of Parliament, during the reign of Queen Victoria (1837–1901); the Queen herself strongly opposed it.[8] The term vivisection referred to the dissection of living animals, with and without anaesthesia, often in front of audiences of medical students.[9] In 1878 there were under 300 experiments on animals in the UK, a figure that had risen to 19,084 in 1903 when the brown dog was vivisected (according to the inscription on the second Brown Dog statue), and to five million by 1970.[10][lower-alpha 1]

Physiologists in the 19th century were frequently criticized for their work.[12] The prominent French physiologist Claude Bernard appears to have shared the distaste of his critics, who included his wife,[13] referring to "the science of life" as a "superb and dazzlingly lighted hall which may be reached only by passing through a long and ghastly kitchen".[14] In 1875, Irish feminist Frances Power Cobbe founded the National Anti-Vivisection Society (NAVS) in London and in 1898 the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection (BUAV). The former sought to restrict vivisection and the latter to abolish it.[15]

The opposition led the British government, in July 1875, to set up the first Royal Commission on the "Practice of Subjecting Live Animals to Experiments for Scientific Purposes".[16] After hearing that researchers did not use anaesthesia regularly—one scientist, Emmanuel Klein told the commission he had "no regard at all" for the suffering of the animals—the commission recommended a series of measures, including a ban on experiments on dogs, cats, horses, donkeys and mules. The General Medical Council and British Medical Journal objected, so additional protection was introduced instead.[17] The result was the Cruelty to Animals Act 1876, criticized by NAVS as "infamous but well-named".[18][lower-alpha 2]

The act stipulated that researchers could not be prosecuted for cruelty, but that the animal must be anaesthetized, unless the anaesthesia would interfere with the point of the experiment. Each animal could be used only once, although several procedures regarded as part of the same experiment were permitted. The animal had to be killed when the study was over, unless doing so would frustrate the object of the experiment. Prosecutions could take place only with the approval of the home secretary. At the time of the Brown Dog affair, this was Aretas Akers-Douglas, who was unsympathetic to the anti-vivisectionist cause.[19]

Ernest Starling and William Bayliss

In the early 20th century, Ernest Starling, professor of physiology at University College London, and his brother-in-law William Bayliss, were using vivisection on dogs to determine whether the nervous system controls pancreatic secretions, as postulated by Ivan Pavlov.[20] Bayliss had held a licence to practice vivisection since 1890 and had taught physiology since 1900.[21] According to Starling's biographer John Henderson, Starling and Bayliss were "compulsive experimenters",[22] and Starling's lab was the busiest in London.[23]

The men knew that the pancreas produces digestive juices in response to increased acidity in the duodenum and jejunum, because of the arrival of chyme there. By severing the duodenal and jejunal nerves in anaesthetized dogs, while leaving the blood vessels intact, then introducing acid into the duodenum and jejunum, they discovered that the process is not mediated by a nervous response, but by a new type of chemical reflex. They named the chemical messenger secretin, because it is secreted by the intestinal lining into the bloodstream, stimulating the pancreas on circulation.[20] In 1905 Starling coined the term hormone—from the Greek hormao ὁρµάω meaning "I arouse" or "I excite"—to describe chemicals such as secretin that are capable, in extremely small quantities, of stimulating organs from a distance.[24]

Bayliss and Starling had also used vivisection on anaesthetized dogs to discover peristalsis in 1899. They went on to discover a variety of other important physiological phenomena and principles, many of which were based on their experimental work involving animal vivisection.[25]

Lizzy Lind af Hageby and Leisa Schartau

.jpg.webp)

Starling and Bayliss's lectures had been infiltrated by two Swedish feminists and anti-vivisection activists, Lizzy Lind af Hageby and Leisa Schartau. The women had known each other since childhood and came from distinguished families; Lind af Hageby, who had attended Cheltenham Ladies College, was the granddaughter of a chamberlain to the king of Sweden.[26][27]

In 1900, the women visited the Pasteur Institute in Paris, a centre of animal experimentation, and were shocked by the rooms full of caged animals given diseases by the researchers. When they returned home, they founded the Anti-Vivisection Society of Sweden, and to gain medical training to help their campaigning, they enrolled in 1902 at the London School of Medicine for Women, a vivisection-free college that had visiting arrangements with other colleges.[26] They attended 100 lectures and demonstrations at King's and University College, including 50 experiments on live animals, of which 20 were what Mason called "full-scale vivisection".[28] Their diary, at first called Eye-Witnesses, was later published as The Shambles of Science: Extracts from the Diary of Two Students of Physiology (1903); shambles was a name for a slaughterhouse.[29] The women were present when the brown dog was vivisected, and wrote a chapter about it entitled "Fun", referring to the laughter they said they heard in the lecture room during the procedure.[30] The following year, a revised edition was published without that chapter; the authors wrote: "The story of the thrice vivisected brown dog as told by its vivisectors to the Lord Chief Justice and a special jury, and as it is found in the verbatim report of the trial, proved the true nature of vivisection far better than the chapter 'Fun' which can now be dispensed with."[31]

The brown dog

Vivisection of the dog

.jpg.webp)

According to Starling, the brown dog was "a small brown mongrel allied to a terrier with short roughish hair, about 14–15 lb [c. 6 kg] in weight". He was first used in a vivisection in December 1902 by Starling, who cut open his abdomen and ligated the pancreatic duct. For the next two months he lived in a cage, until Starling and Bayliss used him again for two procedures on 2 February 1903, the day the Swedish women were present.[23][32]

Outside the lecture room before the students arrived, according to testimony Starling and others gave in court, Starling cut the dog open again to inspect the results of the previous surgery, which took about 45 minutes, after which he clamped the wound with forceps and handed the dog over to Bayliss.[33] Bayliss cut a new opening in the dog's neck to expose the lingual nerves of the salivary glands, to which he attached electrodes. The aim was to stimulate the nerves with electricity to demonstrate that salivary pressure was independent of blood pressure.[34] The dog was then carried to the lecture theatre, stretched on his back on an operating board, with his legs tied to the board, his head clamped and his mouth muzzled.[33]

According to Bayliss, the dog had been given a morphine injection earlier in the day, then was anaesthetized during the procedure with six fluid ounces of alcohol, chloroform and ether (ACE), delivered from an ante-room to a tube in his trachea, via a pipe hidden behind the bench on which the men were working. The Swedish students disputed that the dog had been adequately anaesthetized. They said the dog had appeared conscious during the procedure, had tried to lift himself off the board, and that there was no smell of anaesthesia or the usual hissing sound of the apparatus. Other students said the dog had not struggled, but had merely twitched.[35]

In front of around 60 students, Bayliss stimulated the nerves with electricity for half an hour, but was unable to demonstrate his point.[23] The dog was then handed to a student, Henry Dale, a future Nobel laureate, who removed the dog's pancreas, then killed him with a knife through the heart. This became a point of embarrassment during the libel trial, when Bayliss's laboratory assistant, Charles Scuttle, testified that the dog had been killed with chloroform or the ACE mixture. After Scuttle's testimony, Dale told the court that he had, in fact, used a knife.[33]

Women's diary

On 14 April 1903, Lind af Hageby and Schartau showed their unpublished 200-page diary, published later that year as The Shambles of Science, to the barrister Stephen Coleridge, secretary of the National Anti-Vivisection Society. Coleridge was the son of John Duke Coleridge, former Lord Chief Justice of England, and great-grandson of the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge. His attention was drawn to the account of the brown dog. The 1876 Cruelty to Animals Act forbade the use of an animal in more than one experiment, yet it appeared that the brown dog had been used by Starling to perform surgery on the pancreas, used again by him when he opened the dog to inspect the results of the previous surgery, and used for a third time by Bayliss to study the salivary glands.[36] The diary said of the procedures on the brown dog:

Today's lecture will include a repetition of a demonstration which failed last time. A large dog, stretched on its back on an operation board, is carried into the lecture-room by the demonstrator and the laboratory attendant. Its legs are fixed to the board, its head is firmly held in the usual manner, and it is tightly muzzled.

There is a large incision in the side of the neck, exposing the gland. The animal exhibits all signs of intense suffering; in his struggles, he again and again lifts his body from the board, and makes powerful attempts to get free.[37]

The allegations of repeated use and inadequate anaesthesia represented prima facie violations of the Cruelty to Animals Act. In addition the diary said the dog had been killed by Henry Dale, an unlicensed research student, and that the students had laughed during the procedure; there were "jokes and laughter everywhere" in the lecture hall, it said.[38][39]

Coleridge's speech

According to Mason, Coleridge decided there was no point in relying on a prosecution under the act, which he regarded as deliberately obstructive. Instead he gave an angry speech about the dog on 1 May 1903 to the annual meeting of the National Anti-Vivisection Society at St James's Hall in Piccadilly, attended by 2,000–3,000 people. Mason writes that support and apologies for absence were sent by Jerome K. Jerome, Thomas Hardy and Rudyard Kipling.[40] Coleridge accused the scientists of torture: "If this is not torture, let Mr. Bayliss and his friends ... tell us in Heaven's name what torture is."[41]

Details of the speech were published the next day by the radical Daily News (founded in 1846 by Charles Dickens), and questions were raised in the House of Commons, particularly by Sir Frederick Banbury, a Conservative MP and sponsor of a bill aimed at ending vivisection demonstrations.[42] Banbury asked the Home Secretary to state "under what certificate the operation on a brown dog was performed at University College Hospital on Feb. 2 last; and, whether, seeing that a second operation was performed upon this animal before the wounds caused by the first operation had healed, he proposes to take any action in the matter."[43]

Bayliss demanded a public apology from Coleridge, and, when it had failed to materialize by 12 May, he issued a writ for libel.[42] Ernest Starling decided not to sue; The Lancet, no friend of Coleridge, wrote that "it may be contended that Dr. Starling and Mr. Bayliss committed a technical infringement of the Act under which they performed their experiments."[44] Coleridge tried to persuade the women not to publish their diary before the trial began, but they went ahead anyway, and it was published by Ernest Bell of Covent Garden in July 1903.[45]

Bayliss v. Coleridge

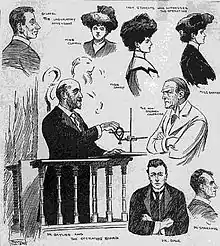

Trial

The trial opened at the Old Bailey on 11 November 1903 before Lord Alverstone, the Lord Chief Justice, and lasted four days, closing on 18 November. There were queues 30 yards long outside the courthouse.[46] Bayliss's barrister, Rufus Isaacs, called Starling as his first witness. Starling admitted that he had broken the law by using the dog twice, but said that he had done so to avoid sacrificing two dogs. Bayliss testified that the dog had been given one-and-a-half grains of morphia earlier in the day, then six ounces of alcohol, chloroform and ether, delivered from an ante room to a tube connected to the dog's trachea. The tubes were fragile, he said, and had the dog been struggling they would have broken.[21]

A veterinarian, Alfred Sewell, said the system Bayliss was using was unlikely to be adequate, but other witnesses, including Frederick Hobday of the Royal Veterinary College, disagreed; there was even a claim that Bayliss had used too much anaesthesia, which is why the dog had failed to respond to the electrical stimulation. According to Bayliss, the dog had been suffering from chorea, a disease that causes involuntary spasm, and that any movement reported by Lind af Hageby and Schartau had not been purposive.[47] Four students, three women and a man, testified that the dog had seemed unconscious.[48]

Coleridge's barrister, John Lawson Walton, called Lind af Hageby and Schartau. They repeated they had been the first students to arrive and had been left alone with the dog for about two minutes. They had observed scars from the previous operations and an incision in the neck where two tubes had been placed. They had not smelled the anaesthetic and had not seen any apparatus delivering it. They said, Mason wrote, that the dog had arched his back and jerked his legs in what they regarded as an effort to escape. When the experiment began the dog continued to "upheave its abdomen" and tremble, they said, movements they regarded as "violent and purposeful".[21]

Bayliss's lawyer criticized Coleridge for having accepted the women's statements without seeking corroboration, and for speaking about the issue publicly without first approaching Bayliss, despite knowing that doing so could lead to litigation. Coleridge replied that he had not sought verification because he knew the claims would be denied, and that he continued to regard the women's statement as true.[21] The Times wrote of his testimony: "The Defendant, when placed in the witness box, did as much damage to his own case as the time at his disposal for the purpose would allow."[49]

Verdict

Lord Alverstone told the jury that the case was an important one of national interest. He called The Shambles of Science "hysterical" and advised the jury not to be swayed by arguments about the validity of vivisection. After retiring for 25 minutes on 18 November 1903, the jury unanimously found that Bayliss had been defamed, to the applause of physicians in the public gallery. Bayliss was awarded £2,000 with £3,000 costs; Coleridge gave him a cheque the next day.[50] The Daily News asked for donations to cover Coleridge's costs and raised £5,700 within four months. Bayliss donated his damages to UCL for use in research; according to Mason, Bayliss ignored the Daily Mail's suggestion that he call it the "Stephen Coleridge Vivisection Fund".[51][52] Gratzer wrote in 2004 that the fund may still have been in use then to buy animals.[53]

The Times declared itself satisfied with the verdict, although it criticized the rowdy behaviour of medical students during the trial, accusing them of "medical hooliganism". The Sun, Star and Daily News backed Coleridge, calling the decision a miscarriage of justice.[51] Ernest Bell, publisher of The Shambles of Science, apologized to Bayliss on 25 November, and pledged to withdraw the diary and pass its remaining copies to Bayliss's solicitors.[54]

The Animal Defence and Anti-Vivisection Society, founded by Lind af Hageby in 1903, republished the book, printing a fifth edition by 1913. The chapter "Fun" was replaced by one called "The Vivisections of the Brown Dog", describing the experiment and the trial.[55][56] The novelist Thomas Hardy kept a copy of the book on a table for visitors; he told a correspondent that he had "not really read [it], but everybody who comes into this room, where it lies on my table, dips into it, etc, and, I hope, profits something".[57] According to historian Hilda Kean, the Research Defence Society, a lobby group founded in 1908 to counteract the antivivisectionist campaign, discussed how to have the revised editions withdrawn because of the book's impact.[58]

In December 1903, Mark Twain, who opposed vivisection, published a short story, A Dog's Tale, in Harper's, written from the point of view of a dog whose puppy is experimented on and killed.[59] Given the timing and Twain's views, the story may have been inspired by the libel trial, according to Mark Twain scholar Shelley Fisher Fishkin. Coleridge ordered 3,000 copies of A Dog's Tale, which were specially printed for him by Harper's.[60]

Second Royal Commission on Vivisection

On 17 September 1906, the government appointed the Second Royal Commission on Vivisection, which heard evidence from scientists and anti-vivisection groups; Ernest Starling addressed the commission for three days in December 1906.[61] After much delay (two of its ten members died and several fell ill), the commission reported its findings in March 1912.[62] Its 139-page report recommended an increase in the number of full-time inspectors from two to four, and restrictions on the use of curare, a poison used to immobilize animals during experiments.[63] The Commission decided that animals should be adequately anaesthetized, and euthanized if the pain was likely to continue, and experiments should not be performed "as an illustration of lectures" in medical schools and similar. All the restrictions could be lifted if they would "frustrate the object of the experiment".[64] There was also a tightening of the definition and practice of pithing. The Commission recommended the maintenance of more detailed records and the establishment of a committee to advise the Secretary of State on matters related to the Cruelty to Animals Act. The latter became the Animal Procedures Committee under the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986.[65]

Brown Dog memorial

In Memory of the Brown Terrier

Dog Done to Death in the Laboratories

of University College in February

1903 after having endured Vivisection

extending over more than Two Months

and having been handed over from

one Vivisector to Another

Till Death came to his Release.

Also in Memory of the 232 dogs

Vivisected at the same place during the year 1902.

Men and Women of England

how long shall these Things be?

—Inscription on the Brown Dog memorial[66]

Original memorial

After the trial Anna Louisa Woodward, founder of the World League Against Vivisection, raised £120 for a public memorial and commissioned a bronze statue of the dog from sculptor Joseph Whitehead. The statue sat on top of a granite memorial stone, 7 ft 6 in (2.29 m) tall, that housed a drinking fountain for human beings and a lower trough for dogs and horses.[67] It also carried an inscription (right), described by The New York Times in 1910 as the "hysterical language customary of anti-vivisectionists" and "a slander on the whole medical profession".[52]

The group turned to the borough of Battersea for a location for the memorial. Lansbury wrote that the area was a hotbed of radicalism—proletarian, socialist, full of belching smoke and slums, and closely associated with the anti-vivisection movement. The National Anti-Vivisection and Battersea General Hospital—opened in 1896, on the corner of Albert Bridge Road and Prince of Wales Drive, and closed in 1972—refused until 1935 to perform vivisection or employ doctors who engaged in it, and was known locally as the "antiviv" or the "old anti".[68] The chairman of the Battersea Dogs Home, William Cavendish-Bentinck, 6th Duke of Portland, rejected a request in 1907 that its lost dogs be sold to vivisectors as "not only horrible, but absurd".[69]

Battersea council agreed to provide space for the statue on its Latchmere Recreation Ground, part of the council's new Latchmere Estate, which offered terraced homes to rent for seven and sixpence a week.[70] The statue was unveiled on 15 September 1906 in front of a large crowd, with speakers that included George Bernard Shaw, the Irish feminist Charlotte Despard, the mayor of Battersea, James H. Brown (secretary of the Battersea Trades and Labour Council), and the Reverend Charles Noel.[71][72]

Riots

November–December 1907

Medical students at London's teaching hospitals were enraged by the plaque. The first year of the statue's existence was a quiet one, while University College explored whether they could take legal action over it, but from November 1907 the students turned Battersea into the scene of frequent disruption.[73]

The first action was on 20 November, when undergraduate William Howard Lister led a group of medical students across the Thames to Battersea to attack the statue with a crowbar and sledgehammer. One of them, Duncan Jones, hit the statue with a hammer, denting it, at which point all ten were arrested by just two police officers.[74][75] According to Mason, a local doctor told the South Western Star that this signalled the "utter degeneration" of junior doctors: "I can remember the time when it was more than 10 policemen could do to take one student. The Anglo-Saxon race is played out."[76]

The students were fined £5 by the magistrate, Paul Taylor, at South-West London Police Court in Battersea and warned they would be jailed next time.[75] This triggered another protest two days later, when medical students from UCL, King's, Guy's, and the West Middlesex hospitals marched along the Strand toward King's College, waving miniature brown dogs on sticks and a life-sized effigy of the magistrate, and singing, "Let's hang Paul Taylor on a sour apple tree / As we go marching on."[77][78] The Times reported that they tried to burn the effigy but, unable to light it, threw it in the Thames instead.[63]

Women's suffrage meetings were invaded, although the students knew that not all suffragettes were anti-vivisectionists. A meeting organized by Millicent Fawcett on 5 December 1907 at the Paddington Baths Hall in Bayswater was left with chairs and tables smashed and one steward with a torn ear. Two fireworks were let off, and Fawcett's speech was drowned out by students singing "John Brown's Body", after which they marched down Queen's Road led by someone with bagpipes. The Daily Express reported the meeting as "Medical Students' Gallant Fight with Women".[79][80]

10 December 1907

As we go walking after dark,

We turn our steps to Latchmere Park,

And there we see, to our surprise,

A little brown dog that stands and lies.

Ha, ha, ha! Hee, hee, hee!

Little brown dog how we hate thee.

—Sung by rioters to the tune of Little Brown Jug[81]

The rioting reached its height five days later, on Tuesday, 10 December, when 100 medical students tried to pull the memorial down. The previous protests had been spontaneous, but this one was organized to coincide with the annual Oxford–Cambridge rugby match at Queen's Club, West Kensington. The protesters hoped (in vain, as it turned out) that some of the thousands of Oxbridge students would swell their numbers. The intention was that, after toppling the statue and throwing it in the Thames, 2,000–3,000 students would meet at 11:30 pm in Trafalgar Square. Street vendors sold handkerchiefs stamped with the date of the protest and the words, "Brown Dog's inscription is a lie, and the statuette an insult to the London University."[82]

In the afternoon, protesters headed for the statue, but were driven off by locals. The students proceeded down Battersea Park Road instead, intending to attack the Anti-Vivisection Hospital, but were again forced back. When one student fell from the top of a tram, the workers shouted that it was "the brown dog's revenge" and refused to take him to hospital.[83] The British Medical Journal responded that, given that it was the Anti-Vivisection Hospital, the crowd's actions may have been "prompted by benevolence".[84]

A second group of students headed for central London, waving effigies of the brown dog, joined by a police escort and, briefly, a busker with bagpipes.[85] As the marchers reached Trafalgar Square, they were 400 strong, facing 200–300 police officers, 15 of them on horseback. The students gathered around Nelson's Column, where the ringleaders climbed onto its base to make speeches. While students fought with police on the ground, mounted police charged the crowd, scattering them into smaller groups and arresting the stragglers, including one undergraduate, Alexander Bowley, who was arrested for "barking like a dog". The fighting continued for hours before the police gained control. At Bow Street magistrate's court the next day, ten students were bound over to keep the peace; several were fined 40 shillings, or £3 if they had fought with police.[86]

Strange relationships

Rioting broke out elsewhere over the following days and months, as medical and veterinary students united. Whenever Lizzy Lind af Hageby spoke, students would shout her down. When she arranged a meeting of the Ealing and Acton Anti-Vivisection Society at Acton Central Hall on 11 December 1906, over 100 students disrupted it, throwing chairs and stink bombs, particularly when she objected to a student blowing her a kiss. The Daily Chronicle reported: "The rest of Miss Lind-af-Hageby's indignation was lost in a beautiful 'eggy' atmosphere that was now rolling heavily across the hall. 'Change your socks!' shouted one of the students." Furniture was smashed and clothing torn.[87][27]

For Susan McHugh of the University of New England, the political coalition of trade unionists, socialists, Marxists, liberals and suffragettes that rallied to the statue's defence reflected the brown dog's mongrel status. The riots saw them descend on Battersea to fight the medical students, even though, she writes, the suffragettes were not a group toward whom male workers felt any warmth. But the "Brown Terrier Dog Done to Death" by the male scientific establishment united them all.[88]

Lizzy Lind af-Hageby and Charlotte Despard saw the affair as a battle between feminism and machismo.[89] According to Coral Lansbury, the fight for women's suffrage became closely linked with the anti-vivisection movement, and the iconography of vivisection struck a chord with women. Three of the four vice-presidents of the National Anti-Vivisection Hospital were women. Lansbury argues that the Brown Dog affair became a matter of opposing symbols: the vivisected dog on the operating board blurred into images of suffragettes force-fed in Brixton Prison, or women strapped down for childbirth or forced to have their ovaries and uteruses removed as a cure for "mania". The "vivisected animal stood for vivisected woman".[90]

Both sides saw themselves as heirs to the future. Hilda Kean writes that the Swedish activists were young and female, anti-establishment and progressive, and viewed the scientists as remnants of a previous age.[58] Their access to higher education had made the case possible, creating what feminist scholar Susan Hamilton called a "new form of witnessing".[91] Against this, Lansbury writes, the students saw themselves and their teachers as the "New Priesthood" and the women and trade unionists as representatives of superstition and sentimentality.[92]

"Exit the 'Brown Dog'"

.jpg.webp)

Questions were asked in the House of Commons about the cost of policing the statue, which required six constables a day at a cost of £700 a year. In February 1908 Sir Philip Magnus, MP for the London University constituency, asked the Home Secretary, Herbert Gladstone, "whether his attention has been called to the special expense of police protection of a public monument at Battersea that bears a controversial inscription". Gladstone replied that six constables were needed daily to protect the statue, and that the overall cost of extra policing had been equivalent to employing 27 inspectors, 55 sergeants, and 1,083 constables for a day.[93]

London's police commissioner wrote to Battersea Council to ask that they contribute to the cost.[94] Councillor John Archer, later Mayor of Battersea and the first black mayor in London,[95] told the Daily Mail that he was amazed by the request, considering Battersea was already paying £22,000 a year in police rates. The Canine Defence League wondered whether, if Battersea were to organize raids on laboratories, the laboratories would be asked to pay the policing costs themselves.[94]

Other councillors suggested the statue be encased in a steel cage and surrounded by a barbed wire fence.[94] Suggestions were made through the letters pages of the Times and elsewhere that it be moved, perhaps to the grounds of the Anti-Vivisection Hospital. The British Medical Journal wrote in March 1910:

May we suggest that the most appropriate resting place for the rejected work of art is the Home for Lost Dogs at Battersea, where it could be "done to death", as the inscription says, with a hammer in the presence of Miss Woodword, the Rev. Lionel S. Lewis, and other friends; if their feelings were too much for them, doubtless an anaesthetic could be administered.[96]

Battersea Council grew tired of the controversy. A new Conservative council was elected in November 1909 amid talk of removing the statue. There were protests in support of it, and the 500-strong Brown Dog memorial defence committee was established. Twenty thousand people signed a petition, and 1,500 attended a rally in February 1910 addressed by Lind af Hageby, Charlotte Despard and Liberal MP George Greenwood. There were more demonstrations in central London and speeches in Hyde Park, with supporters wearing masks of dogs.[6][98]

The protests were to no avail. The statue was quietly removed before dawn on 10 March 1910 by four council workmen, accompanied by 120 police officers. Nine days later, 3,000 anti-vivisectionists gathered in Trafalgar Square to demand its return, but it was clear by then that Battersea Council had turned its back on the affair.[99] The statue was at first hidden in the borough surveyor's bicycle shed, according to a letter his daughter wrote in 1956 to the British Medical Journal,[lower-alpha 3] then reportedly destroyed by a council blacksmith, who melted it down.[101] Anti-vivisectionists filed a High Court petition demanding its return, but the case was dismissed in January 1911.[102]

New memorial

.jpg.webp)

On 12 December 1985, over 75 years after the statue's removal, a new memorial to the brown dog was unveiled by actress Geraldine James in Battersea Park behind the Pump House. Created by sculptor Nicola Hicks, the new bronze dog is mounted on a rectangular plinth of Portland stone and based on Hicks's own terrier, Brock. Three of the four plaques affixed to the column of the current Brown Dog statue bear the original inscriptions.

The British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Edition) published an editorial in March 1986, "A new antivivisectionist libellous statue at Battersea", criticizing Battersea Council and the Greater London Council for allowing it.[103]

Echoing the fate of the previous memorial, the new dog was moved into storage in 1992 by Battersea Park's owners, the Conservative Borough of Wandsworth, they said as part of a park renovation scheme. Anti-vivisectionists campaigned for its return, suspicious of the explanation. It was reinstated in the park's Woodland Walk in 1994, near the Old English Garden, a more secluded spot than before.[104]

The new statue was criticized in 2003 by historian Hilda Kean. She saw the old Brown Dog as a radical statement, upright and defiant: "The dog has changed from a public image of defiance to a pet". For Kean, the new Brown Dog, located near the Old English Garden as "heritage", is too safe; unlike its controversial ancestor, she argues, it makes no one uncomfortable.[105] On 6 September 2021, the 115th anniversary of when the original statue was unveiled, a new campaign was launched by author Paula S. Owen to recast the original statue.[106] Owen is author of Little Brown Dog, a novel that is based on the true story. [107]

See also

- Animal welfare in the United Kingdom

- List of public art in Wandsworth

- Cruel Treatment of Cattle Act 1822

- Cruelty to Animals Act 1835

- Cruelty to Animals Act 1849

- Cruelty to Animals Act 1876

- Wild Animals in Captivity Protection Act 1900

- Protection of Animals Act 1911

- Protection of Animals Act 1934

- Abandonment of Animals Act 1960

- Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986

- Animal Welfare Act 2006

- Animal Health and Welfare (Scotland) Act 2006

- RSPCA

- List of individual dogs

Sources

Notes

- ↑ In 2012, 4.11 million experiments were carried out on animals in the UK, 4,843 of them on dogs.[11]

- ↑ The 1876 Act remained in force until replaced by the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986.

- ↑ Marjorie F. M. Martin (The British Medical Journal, 15 September 1956): "When eventually the Borough Council decided that the statue must be removed, he [the correspondent's father and borough surveyor of Battersea] brought it that night into our bicycle shed, where it was unlikely to be found, until the legal battles were finished. Eventually it was removed to the Corporation yard."[100]

References

- ↑ Baron 1956; Linzey & Linzey 2017, 25.

- ↑ Lansbury 1985, 10–12, 126–127.

- ↑ Ford 2013, 6, 9ff; Lansbury 1985, 14.

- ↑ Mason 1997, 51–56; Lansbury 1985, 14.

- ↑ Kean 2003, 357, citing the Daily Graphic, 11 March 1910.

- 1 2 Kean 1998, 153.

- ↑ "How the cruel death of a little stray dog led to riots in 1900s Britain". the Guardian. 12 September 2021. Retrieved 1 November 2021.

- ↑ Gratzer 2004, 224; Tansey 1998, 20–21.

- ↑ Tansey 1998, 20–21.

- ↑ For 1878 and 1970: Legge & Brooman 1997, 125; for 1903: "Monument to the Little Brown Dog, Battersea Park", Public Monument and Sculpture Association's National Recording Project.

- ↑ "Annual Statistics of Scientific Procedures on Living Animals, Great Britain 2012", Home Office, 2013, 7, 25.

- ↑ Hampson 1981.

- ↑ Rudacille 2000, 19.

- ↑ Bernard 1957, 15.

- ↑ Kean 1995, 25.

- ↑ Hampson 1981, 239; Cardwell 1876.

- ↑ Tansey 1998, 20–21; for Klein, see Rudacille 2000, 39.

- ↑ Hampson 1981, 239; National Anti-Vivisection Society, 24 July 2012. "An Act to amend the Law relating to Cruelty to Animals (15th August 1876)", archive.org.

- ↑ Mason 1997, 10.

- 1 2 Bayliss & Starling 1889.

- 1 2 3 4 Mason 1997, 15.

- ↑ Henderson 2005a, 7.

- 1 2 3 4 Henderson 2005b, 62.

- ↑ Bayliss 1924, 140.

- ↑ Bayliss 1924, 140; for peristalsis, Bayliss & Starling 1889, 106; also see Jones 2003. "Ernest Henry Starling" and "Sir William Maddock Bayliss". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007.

- 1 2 Mason 1997, 7.

- 1 2 "Her Career Arranged by a Little Brown Dog". The Oregon Daily Journal. 7 March 1909, 31.

- ↑ Mason 1997, 7–8.

- ↑ Kean 2003, 359; Lind af Hageby & Schartau 1903.

- ↑ Lansbury 1985, 126;Lind af Hageby & Schartau 1903, 19ff

- ↑ Lind af Hageby & Schartau 1904.

- ↑ "The little brown dog". National Anti-Vivisection Society, accessed 12 December 2013.

- 1 2 3 Mason 1997, 14.

- ↑ Henderson 2005b, 62; Mason 1997, 14

- ↑ Lansbury 1985, 126–127; Mason 1997, 16; Henderson 2005b, 64.

- ↑ Kean 1998, 142; Kean 1995, 20.

- ↑ Lansbury 1985, 126–127.

- ↑ Mason 1997, 9–10.

- ↑ Kean 1998, 142.

- ↑ Mason 1997, 10–12.

- ↑ The Lancet, 30 November 1903; Mason 1997, 10–12.

- 1 2 Mason 1997, 12.

- ↑ "Vivisection at University College, London". The Observer. 10 May 1903. p. 6.

- ↑ Ford 2013, 30, citing The Lancet, 12 December 1903.

- ↑ Henderson 2005b, 65; Lind af Hageby & Schartau 1903.

- ↑ Mason 1997, 12–13.

- ↑ Mason 1997, 15–17.

- ↑ Henderson 2005b, 64.

- ↑ Henderson 2005b, 66.

- ↑ Mason 1997, 17–18.

- 1 2 Mason 1997, 18–20.

- 1 2 "Battersea Loses Famous Dog Statue". The New York Times. 13 March 1910.

- ↑ Gratzer 2004, 226.

- ↑ Lee 1909.

- ↑ Lansbury 1985, 11.

- ↑ "The Brown Dog", NAVS.

- ↑ West 2017, 176.

- 1 2 Kean 1998, 142–143.

- ↑ Twain 1903.

- ↑ Fishkin 2009, 275–277.

- ↑ Henderson 2005b, 67; The British Medical Journal, 19 October 1907.

- ↑ John 1912; The Spectator, 16 March 1912; The British Medical Journal, 16 March 1912.

- 1 2 Tansey 1998, 24.

- ↑ John 1912, 4.

- ↑ The Spectator, 16 March 1912; Tansey 1998, 24.

- ↑ Lansbury 1985, 14; Ford 2013, 6.

- ↑ Mason 1997, 23.

- ↑ Lansbury 1985, 5–8; The British Medical Journal, 30 November 1935.

- ↑ Lansbury 1985, 5–8.

- ↑ Lansbury 1985; "Latchmere Recreation Ground Park Management Plan 2008" Archived 7 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Wandsworth Borough Council, 3, 6.

- ↑ Ford 2013, 6; Lansbury 1985, 14.

- ↑ "Monument to a Dog: Antivivisectionist Memorial Unveiled at Battersea". The Observer. 16 September 1906, 5.

- ↑ Mason 1997, 41.

- ↑ Ford 2013, 7; Mason 1997, 41–47.

- 1 2 "Medical students fined". The Times. 22 November 1907, 13.

- ↑ Mason 1997, 46.

- ↑ Ford 2013, 7; Kean 2003.

- ↑ "Indignant students: The Memorial to the Brown Dog". The Manchester Guardian. 26 November 1907, 4.

- ↑ Ford 2013, 8–9; Lansbury 1985, 17–18.

- ↑ "Students and Woman Suffrage". The Times. 6 December 1907. Issue 38509, 8.

- ↑ Lansbury 1985, 179; Ford 2013, 3.

- ↑ Ford 2013, 9–10.

- ↑ Ford 2013, 12, citing the Daily Chronicle, 15 November 1907; Lansbury 1985, 7.

- ↑ The British Medical Journal, 14 December 1907.

- ↑ Mason 1997, 51.

- ↑ "The Police Courts: Student demonstration". The Times. 12 December 1907. Issue 38514, 15. "Brown Dog Riots". Los Angeles Times. 31 December 1904, 7; Mason 1997, 56.

- ↑ Ford 2013, 15–17.

- ↑ McHugh 2004, 138–139.

- ↑ Birke 2000, 701; Leneman 1997.

- ↑ Lansbury 1985, x, 19, 24.

- ↑ Hamilton 2004, xiv.

- ↑ Lansbury 1985, x, 152ff, 165.

- ↑ "Vivisection—The Battersea Brown Dog". Hansard. Volume 183. 6 February 1908.

- 1 2 3 Mason 1997, 65–66.

- ↑ "John Archer honoured by High Commission of Barbados", Wandsworth Borough Council, 7 April 2017.

- ↑ The British Medical Journal, March 1910.

- ↑ Kean 1998, 155.

- ↑ Kean 2003, 363 (for the masks).

- ↑ Daily Graphic, 11 March 1910, cited in Kean 2003, 364–365; Lansbury 1985, 21.

- ↑ Martin 1956.

- ↑ Kean 2003, 364–365; Lansbury 1985, 21.

- ↑ Cain 2013, 11.

- ↑ "A New Antivivisectionist Libellous Statue At Battersea". British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Edition). 292 (6521): 683. 8 March 1986. JSTOR 29522483.

- ↑ Mason 1997, 110–111.

- ↑ Kean 2003, 368.

- ↑ "How the cruel death of a little stray dog led to riots in 1900s Britain". the Guardian. 12 September 2021. Retrieved 17 October 2021.

- ↑ Owen, Paula S. (2021). Little brown dog. Aberystwyth. ISBN 978-1-912905-44-7. OCLC 1276797733.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Works cited

Books

- Bayliss, W. M. (1924). Principles of General Physiology. London: Longmans.

- Bernard, Claude (1957). An Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine. London: Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 9780486204000.

- Cain, Joe (2013). The Brown Dog in Battersea Park. London: Euston Grove Press.

- Fishkin, Shelley Fisher (2009). Mark Twain's Book of Animals. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Ford, Robert K. (2013) [1908]. The Brown Dog and his Memorial. London: Euston Grove Press. ISBN 978-1-906267-34-6.

- Gratzer, Walter (2004). Eurekas and Euphorias: The Oxford Book of Scientific Anecdotes. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hamilton, Susan (2004). Animal Welfare & Anti-vivisection 1870–1910: Nineteenth Century Woman's Mission. London: Routledge.

- Henderson, John (2005b). A Life of Ernest Starling. New York: Academic Press.

- Kean, Hilda (1998). Animal Rights: Political and Social Change in Britain since 1800. London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 1-86189-014-1.

- Lansbury, Coral (1985). The Old Brown Dog: Women, Workers, and Vivisection in Edwardian England. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0-299-10250-5.

- Legge, Deborah; Brooman, Simon (1997). Law Relating to Animals. London: Cavendish Publishing.

- Lind af Hageby, Lizzy; Schartau, Leisa Katherine (1903). The Shambles of Science: Extracts from the Diary of Two Students of Physiology. London: E. Bell. OCLC 181077070.

- Lind af Hageby, Lizzy; Schartau, Leisa Katherine (1904). The Shambles of Science: Extracts from the Diary of Two Students of Physiology (Fourth ed.). London: The authors.

- Linzey, Andrew; Linzey, Clair (2017). "Introduction. Oxford: The Home of Controversy about Animals". The Ethical Case against Animal Experiments. Chicago: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-08285-6.

- Mason, Peter (1997). The Brown Dog Affair. London: Two Sevens Publishing. ISBN 978-0952985402.

- McHugh, Susan (2004). Dog. London: Reaktion Books.

- Rudacille, Deborah (2000). The Scalpel and the Butterfly: The War Between Animal Research and Animal Protection. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Twain, Mark (1903). A Dog's Tale. New York: Harper & Brothers.

- West, Anna (2017). Thomas Hardy and Animals. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-17917-2.

Journal articles

- "A New Antivivisectionist Libellous Statue At Battersea". British Medical Journal. 292 (6521): 683. 1986. JSTOR 29522483.

- Baron, J. H. (1 September 1956). "The Brown Dog of University College". The British Medical Journal. 2 (4991): 547–548. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4991.547. JSTOR 20359172. S2CID 5447442.

- Bayliss, W. E.; Starling, E. H. (17 March 1889). "The Movements and Innervations of the Small Intestine". The Journal of Physiology. 24 (2): 99–143. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1899.sp000752. PMC 1516636. PMID 16992487.

- Birke, Lynda (2000). "Supporting the Underdog: Feminism, Animal Rights and Citizenship in the Work of Alice Morgan Wright and Edith Goode". Women's History Review. 9 (4): 693–719. doi:10.1080/09612020000200261. PMID 19526659.

- "The Brown Dog and His Friends". The British Medical Journal. 1 (2566): 588–589. 5 March 1910. JSTOR 25289834.

- "Royal Commission On Vivisection, Third Report". The British Medical Journal. 2 (2442): 1078–1083. 19 October 1907. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.2442.1078. JSTOR 20296285. S2CID 36125352.

- "The Statue and the Students". The British Medical Journal. 2 (2450): 1737–1738. 14 December 1907. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.2442.1078. JSTOR 20297039. S2CID 36125352.

- "Royal Commission On Vivisection. Final Report". The British Medical Journal. 1 (2672): 622–625. 16 March 1912. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.2672.622. JSTOR 25296457. S2CID 37846994.

- "Alteration Of A Hospital's Objects". The British Medical Journal. 2 (3908): 1055. 30 November 1935. JSTOR 25346201.

- Hampson, Judith E. (1981). "History of Animal Experimentation Control in the U.K." International Journal for the Study of Animal Problems. 2 (5): 237–241.

- Henderson, John (January 2005a). "Ernest Starling and 'Hormones': An Historical Commentary". Journal of Endocrinology. 184 (1): 5–10. doi:10.1677/joe.1.06000. PMID 15642778.

- Jones, Steve (12 November 2003). "View from the Lab: Why a Brown Dog and Its Descendants Did Not Die in Vain". The Daily Telegraph.

- Kean, Hilda (December 2003). "An Exploration of the Sculptures of Greyfriars Bobby, Edinburgh, Scotland, and the Brown Dog, Battersea, South London, England" (PDF). Society and Animals. 1 (4): 353–373. doi:10.1163/156853003322796082. JSTOR 4289385. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2012.

- Kean, Hilda (Autumn 1995). "The "Smooth Cool Men of Science": The Feminist and Socialist Response to Vivisection". History Workshop Journal. 40 (1): 16–38. doi:10.1093/hwj/40.1.16. JSTOR 4289385. PMID 11608961.

- "Bayliss v. Coleridge". The Lancet. 162 (4186): 1455–1456. 30 November 1903. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(01)36960-x.

- Lee, Frederic S. (4 February 1909). "Miss Lind and Her Views". The New York Times.

- Leneman, Leah (1997). "The Awakened Instinct: Vegetarianism and the Women's Suffrage Movement in Britain". Women's History Review. 6 (2): 271–287. doi:10.1080/09612029700200144. S2CID 144004487.

- Martin, Marjorie F. M. (15 September 1956). "The Brown Dog of University College". British Medical Journal. 2 (4993): 661. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4993.661. JSTOR 20359307. PMC 2035321.

- "The history of the NAVS". National Anti-Vivisection Society. 24 July 2012. Archived from the original on 30 June 2019.

- "The Vivisection Report". The Spectator. 16 March 1912.

- Tansey, E. M. (June 1998). "'The Queen Has Been Dreadfully Shocked': Aspects of Teaching Experimental Physiology using Animals in Britain, 1876–1986". Advances in Physiology Education. 19 (1): 18–33. doi:10.1152/advances.1998.274.6.S18. PMID 9841561.

Royal Commissions

- Cardwell, Edward (1876). Report of the Royal Commission on the Practice of Subjecting Live Animals to Experiments for Scientific Purposes. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office.

- John, Abdel John (1912). Final Report of the Royal Commission on Vivisection. Cd. (Great Britain. Parliament) ;6114. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office.

Further reading

- Bayliss, Leonard (Spring 1957). "The 'Brown Dog' Affair". Potential (UCL magazine). 11–22.

- "Bayliss v. Coleridge". British Medical Journal. 2 (2237): 1298–1300. 1903. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.2237.1298-a. JSTOR 20278410. S2CID 220183908.

- "Bayliss v. Coleridge (contd)". British Medical Journal. 2 (2238): 1361–1371. 1903. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.2238.1361. JSTOR 20278496. S2CID 220240143.

- "Royal Committee on Vivisection". British Medical Journal. 2 (2448): 1597. 1907. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.2448.1597. S2CID 40374360.

- "The 'Brown Dog' of Battersea". British Medical Journal. 2 (2448): 1609–1610. 1907. JSTOR 20296859.

- Coult, Tony (1988). "The Strange Affair of the Brown Dog" (radio play based on Peter Mason's The Brown Dog Affair).

- Coleridge, Stephen (1916). Vivisection, a heartless science. London: John Lane.

- Elston, Mary Ann (1987). "Women and Anti-vivisection in Victorian England, 1870–1900", in Nicolaas Rupke (ed.). Vivisection in Historical Perspective. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415050210

- Gålmark, Lisa (1996). Shambles of Science: Lizzy Lind af Hageby and Leisa Schartau, Anti-vivisektionister 1903–1913/14. Stockholm: Stockholm University. OCLC 924517744

- Gålmark, Lisa (2000). "Women Antivivisectionists, The Story of Lizzy Lind af Hageby and Leisa Schartau". Animal Issues. 4 (2): 1–32.

- Galloway, John (13 August 1998). ""Dogged by controversy" – review of Peter Mason's The Brown Dog Affair". Nature. 394 (6694): 635–636. doi:10.1038/29220. PMID 11645091. S2CID 37893795.

- Harte, Negley; North, John (1991). The World of UCL, 1828–1990. London: Routledge (image of the restaged experiment on the brown dog, 127).

- Le Fanu, James (23 November 2003). "In Sickness and in Health: Vivisection's Undoing". The Daily Telegraph.

- McIntosh, Anthony (1 April 2021). "The Great British Art Tour: The Little Dog that Caused Violent Riots". The Guardian.

Statue locations

- Location of the new Brown Dog, Old English Garden, Battersea Park on Wikimapia (51°28′50.34″N 0°9′44.17″W / 51.4806500°N 0.1622694°W)

- Location of the old Brown Dog (now empty), Latchmere Recreation Ground on Wikimapia (51°28′18.47″N 0°9′42.55″W / 51.4717972°N 0.1618194°W)

.jpg.webp)