| Capture of Wejh | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Arab Revolt on the Middle Eastern theatre of the First World War | |||||||

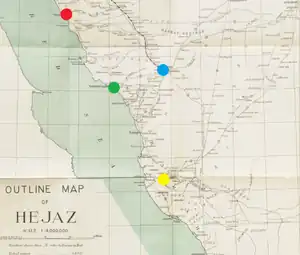

Contemporary British map of Hejaz marked with the locations of Wejh (red), Yenbo (green), Medina (blue) and Mecca (yellow) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

The capture of Wejh (modern-day Al Wajh, Saudi Arabia) took place on 23–24 January 1917 when British-led Arab forces landed by sea and, with the support of naval bombardments, defeated the Ottoman garrison. The attack was intended to threaten the flanks of an Ottoman advance from their garrison in Medina to Mecca, which had been captured by Arab forces in 1916. The sea-based force was to have attacked in co-operation with a larger force under Arab leader Faisal but these men were held up after capturing a quantity of supplies and gold en-route to Wejh. The sea-based force under Royal Navy leadership captured Wejh with naval artillery support, defeating the 1,300-strong Ottoman garrison. The capture of the town safeguarded Mecca, as the Ottoman troops were withdrawn to static defence duties in and around Medina.

Background

The Arab Revolt began in June 1916 when disaffected Arab tribesmen unsuccessfully rose against the Ottoman garrisons at the Islamic holy cities of Mecca and Medina. The tribesmen secured the surrender of the garrison at Mecca by means of a siege and blockade but were thwarted by Ottoman reinforcements rushed by rail to Medina.[1] The Ottoman force began an advance towards Mecca, some 200 miles (320 km) to the south, the approaches to which were lightly defended.[2] The British, through T. E. Lawrence, the British liaison officer with Arab leader Faisal, proposed an Arab force be moved behind the Ottoman lines to threaten the communications along the Hejaz Railway.[3]

Action

Lawrence and the Arab tribesmen under Faisal were to march 200 miles (320 km) north, from the coastal town to Yanbu (Yenbo), along the Red Sea coast to the port of Wejh (now known as Al Wajh).[3] Faisal was anxious about leaving Yanbu, a coastal town near Medina, which he considered vulnerable to attack. He was assured by British liaison officer Colonel Cyril Wilson that the troops left there could resist any attack, with the assistance of the Royal Navy. Wilson knew this was by no means certain but thought Faisal would not agree to attack Wejh without this reassurance.[4] Faisal led 10,000 men, around half mounted on camels, northwards from his camp near Yanbu on 4 January.[5]

The Royal Navy arrived at Wejh on 23 January but there was no sign of Faisal's Arabs.[6] The navy's six ships, mounting 50 guns, under the command of Captain William Boyle opened first on the Ottoman positions. The gunfire was directed by a Royal Navy seaplane. With the navy was a force of 550 Arabs under the British Army's Major Charles Vickery and Captain Norman Bray.[7][5] A party of these men, under Vickery, were landed on shore to secure a suitable landing site for the remainder.[6]

On 24 January the Arab force was put ashore and commenced an attack on the Ottoman forces, but there was still no sign of Faisal or Lawrence.[8][9] Around half of the landing force, relatively untrained and inexperienced, refused to fight but the remainder, encouraged by the prospect of loot, attacked. The Ottoman forces, some 800 Turkish soldiers and a 500-strong camel-mounted Arab contingent, were defeated in street-to-street fighting, with significant assistance from the naval bombardment. They were forced out of the town and retreated inland, with forces remaining in the town taken captive. Faisal and Lawrence arrived two days after the fight, with Lawrence blaming a lack of water for their delayed arrival. The actual cause was that a party of Arabs under Abdullah had captured a senior Ottoman officer, Ashraf Bey, and a column of supplies carrying £20,000 of gold near Wadi Ais and Faisal's men had taken time to celebrate this and attempt to acquire some of the gold.[9]

Aftermath

The attack forced the Ottoman army marching on Mecca to return to Medina, as their right flank was threatened. At Medina around half the force was committed to the defence of the town while the remainder was distributed along the railway. This marked a switch in tactics for the Ottomans from offensive action against the Arab Revolt to a defence posture.[3] Medina remained in Ottoman hands for the rest of the war but Lawrence realised that he could occupy almost the entirety of the rest of the Hejaz and leave the garrison there isolated.[10] The Ottomans refused to follow German advice to abandon Medina as strategically insignificant due to its prestige as a holy place. The garrison there required 14,000 troops plus around 11,000 on the railroad, which could otherwise have been deployed in offensive action against the Arabs.[11] The capture of Wejh safeguarded Yanbu and Mecca as an Arab force at Wejh could threaten the flanks of any Ottoman advance upon them from Medina.[11]

After the battle Faisal moved his headquarters to Wejh from Tabuk and used it to plan an attack on the port of Aqaba, some 230 miles (370 km) to the north.[12] The Arabs used Wejh and, after its July 1917 capture, Aqaba as sea ports to supply their operations up to 300 miles (480 km) into the interior.[13]

The capture of Wejh was a major achievement for the Arabs and demonstrated the potential for British-Arab co-operation on this front. The battle helped to demonstrate to the Arabs that the Ottoman forces could be defeated. After the battle British aid to the Arabs, sent from Egypt, markedly increased.[14] This included aircraft and armoured cars delivered to Wejh in the weeks after its capture.[15]

References

- ↑ Lawrence, T.E. (October 1920). "The Evolution of a Revolt". Army Quarterly and Defence Journal: 1.

- ↑ Lawrence, T.E. (October 1920). "The Evolution of a Revolt". Army Quarterly and Defence Journal: 3.

- 1 2 3 Lawrence, T.E. (October 1920). "The Evolution of a Revolt". Army Quarterly and Defence Journal: 4.

- ↑ Walker, Philip (2018). Behind the Lawrence Legend: The Forgotten Few Who Shaped the Arab Revolt. Oxford University Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-19-880227-3.

- 1 2 Walker, Philip (2018). Behind the Lawrence Legend: The Forgotten Few Who Shaped the Arab Revolt. Oxford University Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-19-880227-3.

- 1 2 Walker, Philip (2018). Behind the Lawrence Legend: The Forgotten Few Who Shaped the Arab Revolt. Oxford University Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-19-880227-3.

- ↑ Norman, Andrew (24 January 2017). T.E.Lawrence: Tormented Hero. Fonthill Media. p. 41.

- ↑ Bradford, James C. (1 December 2004). International Encyclopedia of Military History. Routledge. p. 2344. ISBN 978-1-135-95033-0.

- 1 2 Walker, Philip (2018). Behind the Lawrence Legend: The Forgotten Few Who Shaped the Arab Revolt. Oxford University Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-19-880227-3.

- ↑ Lawrence, T.E. (October 1920). "The Evolution of a Revolt". Army Quarterly and Defence Journal: 6.

- 1 2 Allawi, Ali A. (11 March 2014). Faisal I of Iraq. Yale University Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-300-12732-4.

- ↑ Infantry. U.S. Army Infantry School. 2005. p. 22.

- ↑ Lawrence, T.E. (October 1920). "The Evolution of a Revolt". Army Quarterly and Defence Journal: 14.

- ↑ Chatterji, Nikshoy C. (1973). Muddle of the Middle East. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 978-0-391-00304-0.

- ↑ Allen, John Johnson (30 June 2015). T.E.Lawrence and the Red Sea Patrol: The Royal Navy's Role in Creating the Legend. Pen and Sword. p. 99. ISBN 978-1-4738-3800-0.