The Cardan grille is a method of writing secret messages using a grid.

History

This technique was used in ancient China.[1]

In 1550, Girolamo Cardano (1501–1576), known in French as Jérôme Cardan, proposed a simple grid for writing hidden messages. He intended to cloak his messages inside an ordinary letter so that the whole would not appear to be a cipher at all.

Such a disguised message is considered to be an example of steganography, which is a sub-branch of general cryptography. But the name Cardan was applied to grilles that may not have been Cardan's invention, and, so, Cardan is a generic name for cardboard grille ciphers.

Cardinal Richelieu (1585–1642) was reputed to be fond of the Cardan grille and to have used it in both private and diplomatic correspondence. Educated men in 17th century Europe were familiar with word games in literature, including acrostics, anagrams, and ciphers.

Although the original Cardan grilles were little used by the end of the 17th century, they still appeared occasionally in the form of masked letters and as literary curiosities. George Gordon Byron, for example, claimed to have written Cardan-grille verse – but as a demonstration of verbal skill rather than a serious cipher.

Alternative grilles possess apertures for single letters only and can be used quickly. Messages are filled out with a jumble of letters or numbers and are clearly cryptograms whereas Cardano intended to create steganograms.

These single-letter grilles may be named after Cardano, but they are also called simply cardboard ciphers.

A further variation is a turning grille or trellis, based on the chess board, which was used in the latter 16th century.

The turning grille reappeared in a more sophisticated form at the end of the 19th century; but, by this time, any connection with Cardano was in name alone.

Construction

A Cardan grille is made from a sheet of fairly rigid paper or parchment, or from thin metal. The paper is ruled to represent lines of handwriting and rectangular areas are cut out at arbitrary intervals between these lines.

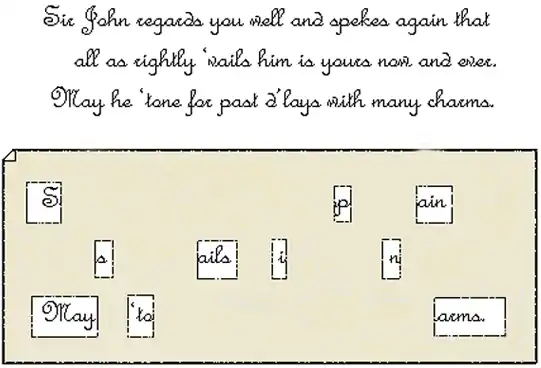

An encipherer places the grille on a sheet of paper and writes his message in the rectangular apertures, some of which might allow a single letter, a syllable, or a whole word. Then, removing the grille, the fragments are filled out to create a note or letter that disguises the true message. Cardano suggested drafting the text three times in order to smooth any irregularities that might indicate the hidden words.

The recipient of the message must possess an identical grille. Copies of grilles are cut from an original template, but many different patterns could be made for one-to-one correspondence.

The grille can be placed in four positions – face up and face down, upright and reversed – which increases the number of possible cell positions fourfold.

In practice it can be difficult to construct an innocent message around a hidden text. Stilted language draws attention to itself and the purpose of the Cardan grille is to create a message “without suspicion” in the words of Francis Bacon. But the task was easier for Cardano, because 16th century spelling was not standardised and left much room for contractions and adornments of penmanship.

Detection of messages

When executed badly, a Cardan message stands out because of stilted language and uneven writing. An analyst may attempt to reconstruct the grille when there are several examples of suspect messages from a correspondent.

When executed well, a Cardan message can be difficult to spot. Even when an analyst suspects the presence of a message, an innocent letter can contain apparently hidden text. So, in practice, the only solution is to obtain the grille itself.

Disadvantages

The method is slow and requires literary skill. Above all, any physical cipher device is subject to loss, theft and seizure; so to lose one grille is to lose all secret correspondence constructed with that grille. Possession of a grille may be incriminating.

The Cardan grille, in its original form, is of more literary than cryptographic interest. For example, controversy surrounds the Voynich manuscript which could be a 16th-century fake cipher text, possibly constructed with a Cardan grille which was used to generate pseudo-random nonsense from a pre-existing text.[2]

See also

References

- ↑ Fabien A. P. Petitcolas and Stefan Katzenbeisser. Information Hiding Techniques for Steganography and Digital Watermarking. 2000.

- ↑ Nature news article: World's most mysterious book may be a hoax (2003), a summary of Gordon Rugg's paper

- David Kahn, The Codebreakers — The Comprehensive History of Secret Communication from Ancient Times to the Internet, 1996, ISBN 0-684-83130-9.